Altered liver values are not infrequently incidental findings during routine diagnostics. Fatty liver, alcohol abuse, and viral hepatitis are the most common causes of elevated transaminases. Often, several liver diseases are present at the same time. In the case of a positive hepatitis B or C test result, therapy can be administered by the general practitioner under certain conditions.

Since liver diseases often do not cause specific symptoms, they remain undetected for a long time in many cases. In the case of incidental findings of altered liver values, further laboratory tests form the basis, explains Beat Helbling, MD, gastroenterologist, from the Gastroenterology Bethanien Group Practice, Zurich [1]. A variety of hepatic and extrahepatic diseases as well as various noxious agents are possible causes, and a careful differential diagnostic workup must be performed, including a history of medication use and alcohol consumption.

Significant prognostic implications

The literature reports a 4- to 8-fold increase in liver-related mortality [2–4]. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT/GPT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST/GOT) leak from damaged liver cells and are sensitive indicators of liver damage. “If you want to assess an acute situation, you have to look at the AST in a focused way,” the speaker explained. Aspartate aminotransferase increases rapidly due to toxic effects (e.g. alcohol) and decreases again after the noxious substance has disappeared from the organism. In contrast, an elevation of alanine aminotransferase may indicate a more distant event. In most cases, these are mild elevations of AST/ALT (<5-fold elevation). In addition to transaminases, cholestasis levels should also be determined.

What is the pattern of liver value changes?

Simultaneous determination of AST, ALT, and γ-GT (γ-gamma-glutamyltransferase) levels can detect more than 95% of all liver diseases [2,5]. A distinction is made between a hepatic picture with leading elevation of AST and ALT, a cholestatic picture with dysproportional elevation of γ-GT and alkaline phosphatase (AP), and a toxic picture in which γ-GT in particular is markedly elevated [2].

Further differential diagnostic indications are provided by the determination of the de-ritis quotient, i.e. the ratio of AST and ALT. Most hepatic disease patterns are associated with an AST/ALT ratio <0.7. A quotient of >2 and an elevated γ-GT at the same time indicate a high probability of alcoholic liver disease; advanced fibrosis may also be the cause. In addition to γ-GT, AST/ALT, and the de-ritis quotient, MCV levels and, if appropriate, bilirubin and serum IgA levels may also be informative. “Bilirubin only increases when the liver’s ability to excrete is reduced by more than half, so it’s a sluggish process,” the speaker added.

If massively elevated AST/ALT values are present, this is indicative of acute hepatocellular necrosis or injury, which is usually due to acute viral hepatitis, toxin- or drug-induced hepatitis, or ischemic hepatitis, and infarction should also be considered as a possible cause.

Tested positive for hepatitis B or C: What next?

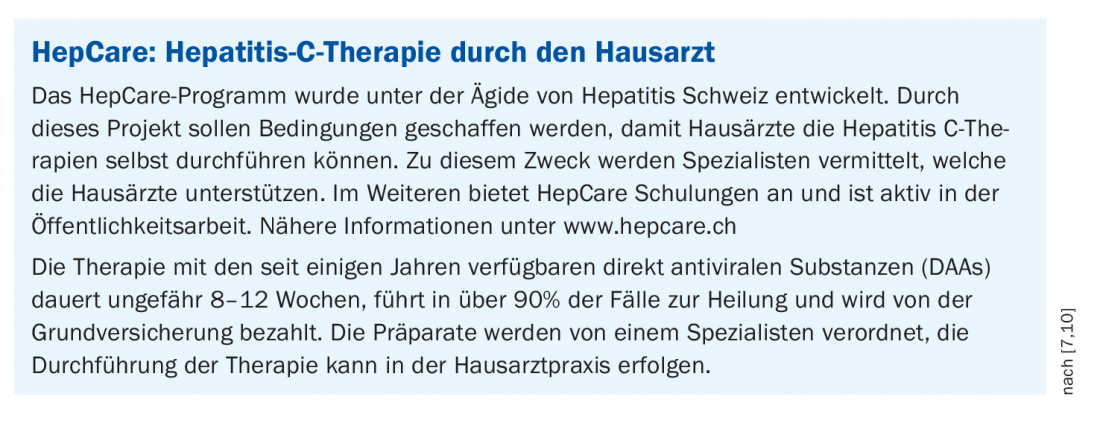

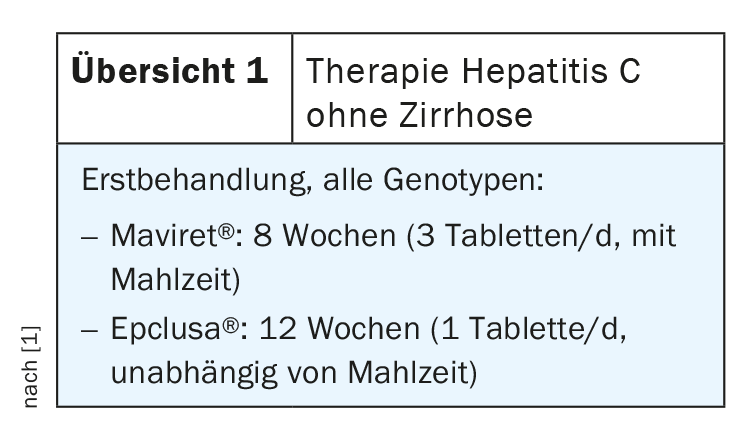

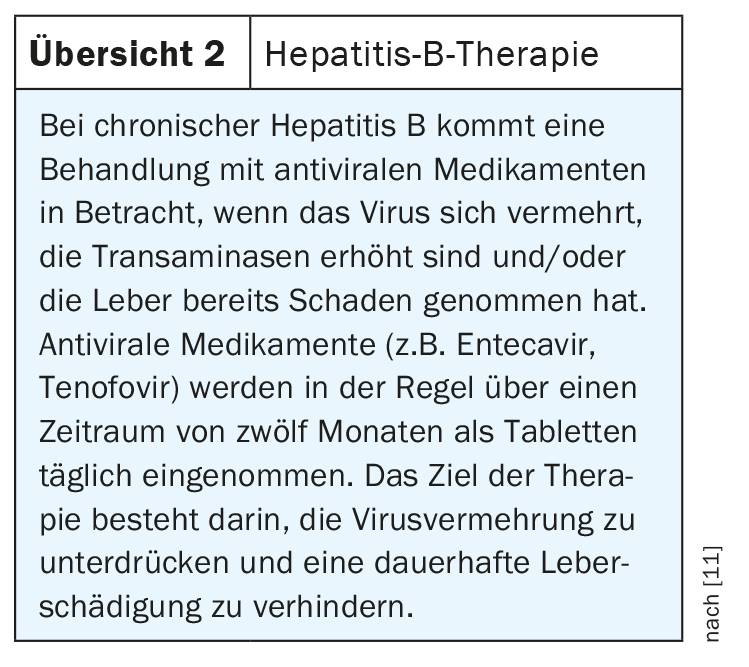

Screening for chronic viral hepatitis is essential, even though the prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis is relatively low in our latitudes. Testing should be performed for both chronic hepatitis B virus infection (HBs antigen, anti-HBc) and hepatitis C virus infection (anti-HCV). If the hepatitis C test result is positive, the two combination drugs Maviret® and Epclusa® are now available (overview 1) [6]. “The therapy is extremely well tolerated, with patients being cured in over 95% of cases,” Dr. Helbling said. In 80% of hepatitis C patients, these are those without cirrhosis, and therapy can be administered by the primary care physician under the conditions described in the “HepCare” program (box) [7,10]. This project to improve interdisciplinary networking was developed in collaboration with the Center for Addiction Medicine (ARUD). After successful HCV therapy, antibody remains positive, whereas RNA is negative. Noncirrhotic patients are considered cured three months after completion; cirrhotic patients continue to be indicated for sonography every 6 months because the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains. HCV treatment in the presence of cirrhosis is somewhat more complicated and should be performed by specialists. There are also good drugs for hepatitis B that can be used for antiviral therapy. The indication is shown in overview 2.

In addition to chronic viral hepatitis, alcohol consumption, and liver diseases such as autoimmune hepatitis or hemochromatosis, metabolic syndrome (obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypercholesterolemia) is another possible cause that is also relatively common.

In these cases, monitoring is initially sufficient

If there are only moderate changes in liver values, i.e. <2×ULN (“upper limit of normal”), the patient is symptom-free and there are no indications of liver insufficiency, it is possible to wait for the time being. A new laboratory control should be performed after 1-3 months [2,8]. Sonographic examination is recommended in all patients with persistently abnormal liver values. More than half of the incidences of elevated transaminases are

caused by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is characterized by a typical hyperechogenic liver parenchyma on ultrasound. Alcohol abuse is also a relatively common cause. Further laboratory testing is required to detect genetic liver disease. The most common hereditary liver disease – hemochromatosis – can be detected by determining transferrin saturation (cut-off >45%) and ferritin. Rarer genetic hepatopathies include Wilson disease or alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

In which cases is a liver biopsy useful? For example, for the diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and autoimmune hepatitis, for the quantification of copper or iron overload in Wilson’s disease and hemochromatosis, respectively, and for clarifying the indication for therapy in hepatitis B infection [2,9]. In primary cholestatic liver disease, only liver biopsy allows a definitive diagnosis in certain cases, such as small-duct PSC or granulomatous liver disease.

Source: FomF General and Internal Medicine

Literature:

- Helbling B: Transaminases, chloestasis, icterus. Beat Helbling, MD. FomF General and Internal Medicine, Dec. 03, 2020.

- Zimmermann HW, et al: Dtsch Arztebl 2016; 113(22-23): A-1104/B-924/C-910

- Ruhl CE, Everhart JE: Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 477-485; e411.

- Unalp-Arida A, Ruhl CE: Hepatology 2015; DOI: 10.1002/hep.28390. [Epub ahead of print CrossRef

- Dollinger MM, Fechner L, Fleig WE: Internist (Berl) 2005; 46: 411-420.

- Swiss Drug Compendium. https://compendium.ch

- HepCare: www.hepcare.ch

- Smellie WS, Ryder SD: BMJ 2006; 333: 481-483 CrossRef MEDLINE PubMed Central.

- Tannapfel A, Dienes HP, Lohse AW: Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012; 109: 477-483.

- Hepatitis Switzerland, www.hepatitis-schweiz.ch

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH): Hepatitis B: Causes, Consequences, Prevention. 2014, www.bag.admin.ch, (last accessed 04.03.2021)

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(3): 24-25 (published 9/3/21, ahead of print).