The first SGAIM Spring Congress in Basel also hosted the Swiss Geriatric Society. Prof. Dr. med. Andreas Schönenberger, Head of Geriatrics, Spital Tiefenau, held a workshop on the therapy of hypertension in geriatric patients. The interest in the topic had apparently been underestimated by the congress organizers: Only a small room was reserved for the workshop, so that many listeners had to stand or sit on the floor. But they were rewarded with a lot of practical information and tips.

In the Swiss population, about 60% of all persons over 65 years of age have hypertension. Of course, the question arises whether a “disease” that is so common can still be called a disease at all. “Wouldn’t it make more sense to simply adjust what are considered normal blood pressure values upward in older people?” asked Prof. Andreas Schönenberger a somewhat provocative question – and he answered it himself right away. “Unfortunately, as we age, not only do blood pressure levels increase, but so do the corresponding consequences, such as stroke, heart attack or heart failure. And the older the age, the higher the risk. Since we can treat blood pressure these days and prevent these consequences, it makes sense not to adjust what are considered normal blood pressure levels upward with age.”

Special features for the elderly

Hypertension in the elderly is characterized by some peculiarities. The incidence of isolated systolic hypertension increases with age, exceeding 90% in those over 70 years of age. In elderly patients, it is particularly important when measuring blood pressure that both sitting and standing positions are used. The reason for this is the higher probability of orthostatic hypotension.

Two other problems to be considered in blood pressure measurement are pseudo-hypotension and hypotension. Pseudo-hypotension may be present when a falsely low blood pressure is measured because of stenoses in the arm vessels. Pseudo-hypertension, on the other hand, exists when falsely high values are measured; the reason for this is severely sclerosed vessels that cannot be fully compressed during blood pressure measurement. “Think of possible pseudo-hypertension in patients who have been hypertensive for a long time but have no organ damage, and who tolerate the drugs poorly,” the speaker reminded.

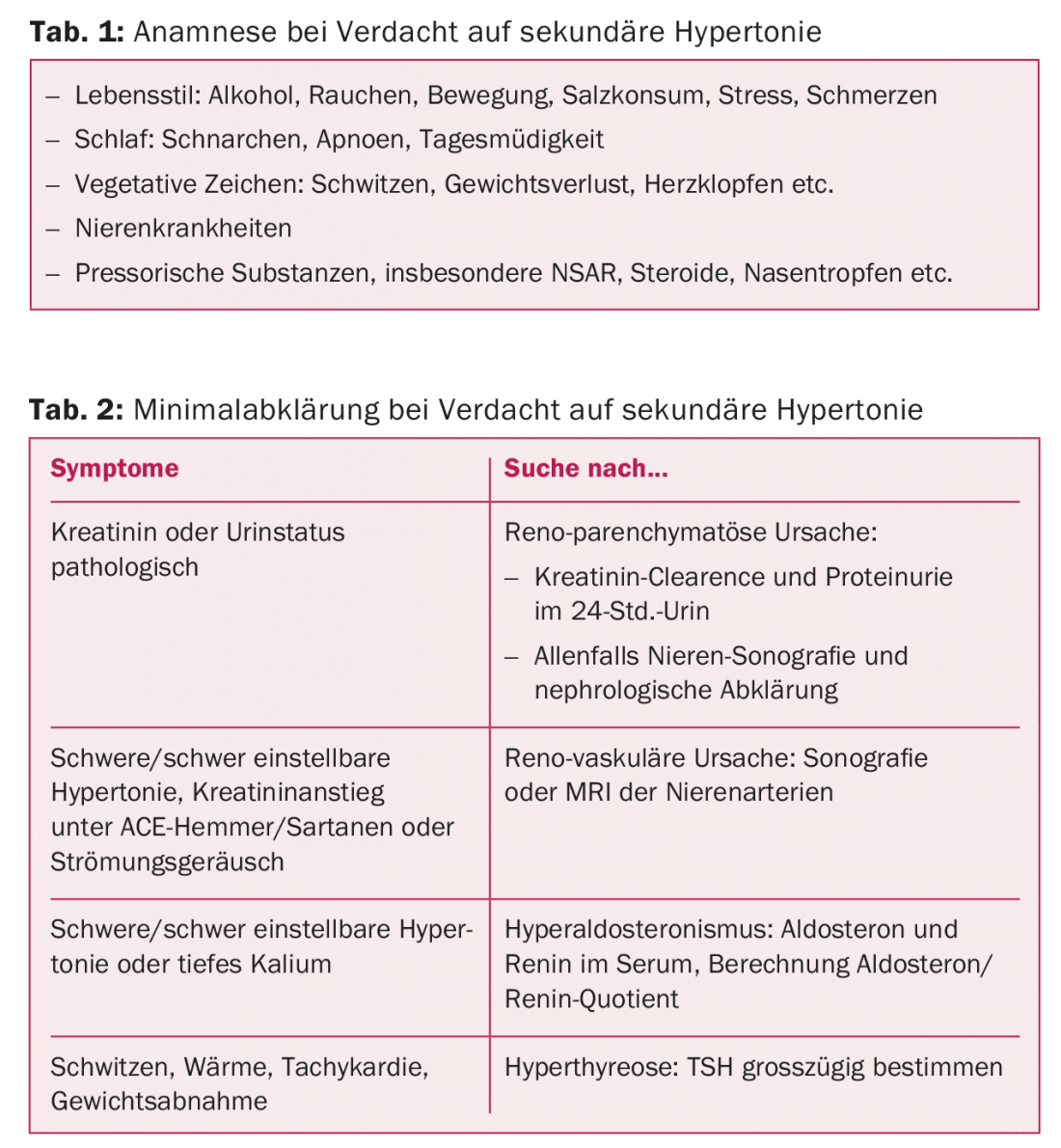

Especially in elderly patients, 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure measurement should be used in a low-threshold manner – especially if the diagnosis of hypertension is unclear, if blood pressure values fluctuate greatly, or if white coat hypertension is suspected. In elderly patients, a minimal workup is also useful with regard to secondary hypertension. An accurate history, a few clinical examinations (weight, flow sounds), and a minimal laboratory often help here (tables 1 and 2).

Prof. Schönenberger drew particular attention to psychological stress factors: “As a hospital physician, I do not usually try to adjust blood pressure perfectly, because in hospitalized patients the values are often elevated as a result of stress, pain, etc. Adjusting blood pressure is the job of primary care providers and family physicians once the patient is back home.” In the search for end-organ damage from hypertension, Schönenberger advocated not forgetting the brain and using low-threshold tests to measure cognition.

Less salt, fewer kilos, enough antihypertensives

Salt restriction (less than 6 g of salt per day) is often particularly effective in the elderly. It makes sense not to add salt at the table or not to add salt during cooking and to use salt only at the table. Weight reduction by 10% of body weight can lower blood pressure by up to 10 mmHg, so it works just as well as medication. However, weight reduction in the elderly is a double-edged sword, because any weight reduction will also lose muscle. If muscle loss cannot be minimized by simultaneous physical activity, weight reduction is even dangerous, because the elderly patient can only poorly make up for the muscle loss. Therefore, a weight loss program should only be recommended if physical activity can be increased at the same time.

For drug therapy, the same guidelines apply to the elderly as to younger people (Swiss Hypertension Society, www.swisshypertension.ch). However, comorbidities that influence medication choice are more common with age. Since many elderly people suffer from coronary artery disease (CAD), beta-blockers are often the first-choice antihypertensives for them. About one in 10 patients taking an ACE inhibitor suffers from cough. For this reason, some primary care physicians give a sartan directly without first prescribing an ACE inhibitor. The speaker indicated that sartans are significantly more expensive than ACE inhibitors and that substantial health care costs can be saved if therapy with an ACE inhibitor is tried first.

What target values to aim for?

In terms of blood pressure targets, there have been ups and downs over the past 30 years. At the end of last year, there was a veritable confusion of different recommendations internationally. And now comes the SPRINT trial! Prof. Schönenberger pointed out that there were an enormous number of exclusion criteria in the SPRINT trial: among others, diabetics, patients with CHD or previous cerebral stroke, patients with dementia or reduced life expectancy, and also residents of a retirement or nursing home were excluded – i.e., virtually all elderly patients in an average family practice [1]. “The results of the SPRINT trial apply primarily to fit, healthier elderly people,” the speaker emphasized.

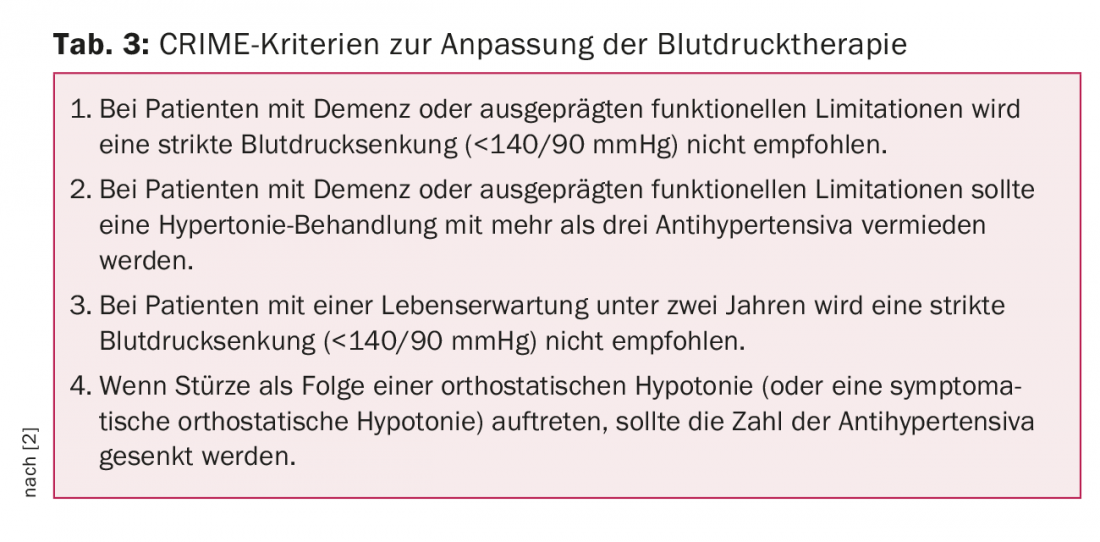

Biological diversity varies widely among the elderly: a family physician cares for both healthy, fit 80-year-olds and very sick 80-year-olds in a nursing home. It is important to adapt the blood pressure target values to the patient’s condition: “If a patient has a life expectancy of less than two years, it is certainly not reasonable to aim for a blood pressure below 140 mmHg at any cost.” An important guideline in this area is the CRIME criteria (Table 3) [2]. At the same time, however, Prof. Schönenberger pointed out that in Switzerland, 90-year-olds still have an average life expectancy of five years, which means that lowering blood pressure is generally worthwhile.

Cognition plays a critical role in individuals at such an advanced age. This should be measured systematically. The gold standard is still the Mini Mental Test (MMSE) in combination with the watch test. However, many patients find the MMSE patronizing, so the MOCA test with its more playful elements is a good alternative. Another valid cognition test with a very low time requirement is the Mini-COG.

Do not forget orthostatic hypotension

An important aspect of hypertension treatment in the elderly is orthostatic hypotension, the prevalence of which increases sharply in old age, for example, because of increasing autonomic dysfunction or varicosis. Prof. Schönenberger provided tips and tricks on how to prevent orthostatic hypotension and other forms of hypotension. Falls in elderly patients can be prevented:

- Avoid triggering drugs and substances (alcohol!)

- Wear support stockings

- Observe rules of conduct: get up slowly, move feet through before getting up, raise top of bed slightly at night, etc.

- Walking exercise to train the muscle pump

- Avoid standing for long periods

- Avoid heat and dehydration

Take-home-messages

- Relax blood pressure targets if life expectancy is expected to be less than 1-2 years, especially in advanced dementia.

- Determine target values in elderly patients individually, depending on biological age and drug tolerance.

- In fit older patients and well tolerated by therapy, aim for the same target values as in younger patients.

- Keep an eye on reduced perfusion of the organs (brain, kidney, heart) and relax blood pressure targets if necessary.

- Keep an eye on orthostatic hypotension, relax blood pressure targets if necessary.

Source: 1st Spring Meeting of the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine, May 25-27, 2016, Basel. Workshop: Treatment of hypertension in the elderly.

Literature:

- SPRINT Research Group: A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med 2015 Nov; 373(22): 2103-2116.

- Onder G, et al: Recommendations to prescribe in complex older adults: results of the CRIteria to assess appropriate Medication use among Elderly complex patients (CRIME) project. Drugs Aging 2014; 31(1): 33-45.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(4): 29-31