Reactivation of early childhood attachment experiences can shape and challenge the doctor-patient relationship. Because the A-P relationship has been shown to be the foundation for improved treatment outcomes, increased adherence, and greater patient and practitioner satisfaction, measures to promote a good quality relationship are very relevant.

How would you feel, with the most severe back pain and fever, in a crowded emergency department waiting for hours for the doctor on duty? Or, in a distant country, lying on the gurney of a chaotic-looking hospital after a motorcycle accident – your loved ones far away? How does it feel to be a patient who, in need, goes to medical care for help and relief?

What patterns are activated when we are most in need of help? What role do attachment styles established in early childhood play in this process?

Robert Maunder and Jonathan Hunter addressed these questions in depth in their 2015 book, Love, Fear, and Health: How Our Attachments to Others Shape Health and Health Care, examining the doctor-patient relationship from the perspective of attachment theory [1].

Inspired by a lecture given by Robert Maunder at last year’s congress of the European Association of Psychosomatic Medicine in Luleå/Sweden and the subsequent reading of his book, a lecture at Medidays 2017 in Zurich and this article were written.

The doctor-patient relationship (A-P relationship) has been studied systematically since the 1960s. One of the pioneers, Michael Balint (1896-1970), a Hungarian physician and psychoanalyst, recognized the “drug doctor” early on. He saw the A-P relationship as a site of re-enactment of old relational patterns and recognized that important insights into the patient’s conflicts are gained through interaction and can be an aid in diagnosis [2].

The attachment theory in brief

John Bowlby (1907-1990), British pediatrician and psychoanalyst, the first to systematically study infants and young children, founded attachment theory in the 1950s. According to Bowlby, the attachment system is a primary, genetically anchored motivational system that is activated in a certain biological preformedness after birth and has survival-securing functions. It leads to a strong need for contact with certain persons and is a permanent, largely stable, and situation-independent characteristic of the attachment seeker. Attachment behavior leads to the search for closeness to a supposedly more competent person; it appears most clearly in cases of anxiety, fatigue, illness, and corresponding needs for attention or care. It is fundamentally determined by early childhood experiences in the relationship with primary attachment figures [3].

Inseparably linked to attachment theory is the work of the American-Canadian developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth (1913-1999). In “The Strange Situation,” the behavioral experiment of attachment theory, the reactions of infants 12-18 months of age to separation from and reunion with their primary attachment figure are observed. Ainsworth operationalized four attachment styles from the responses: securely attached, insecure-avoidant, insecure-ambivalent, and disorganized.

Securely attached children respond to separation (attachment figure leaves the room for three minutes) by attempting to follow the attachment figure. If this fails, they become sad, desperate and start to cry. After reuniting, they soon settle down and eventually return to their game. Insecure-avoidant children show no visible emotional response to separation and do not seem interested in the attachment figure after reunification. Insecure-ambivalent children react with a fierce emotional response and alternate between angry avoidance and close contact upon return and can hardly be calmed down. Insecure-disorganized children appear distraught, as if frozen, or move stereotypically when their mother returns [4].

According to Prof. Dr. phil. Guy Bodenmann, Chair of Clinical Psychology at the University of Zurich, 45% of Swiss children are insecurely attached, most of them insecure-avoidant [5].

How do attachment styles develop and what are their effects?

Attachment style is fundamentally influenced by the sensitivity of primary attachment figures in early childhood and usually persists throughout life. “Sensitivity,” a term coined by Ainsworth, means adequately interpreting the infant’s signals and responding appropriately and promptly. These finely balanced interactions result in a wide range of skills and abilities that enable children and later adults to move safely in the world.

Securely attached people have, among other things, multiple internal and external sources to calm themselves, move more competently in social interactions, perceive their emotions in a more differentiated way, and can put what they experience into words [4].

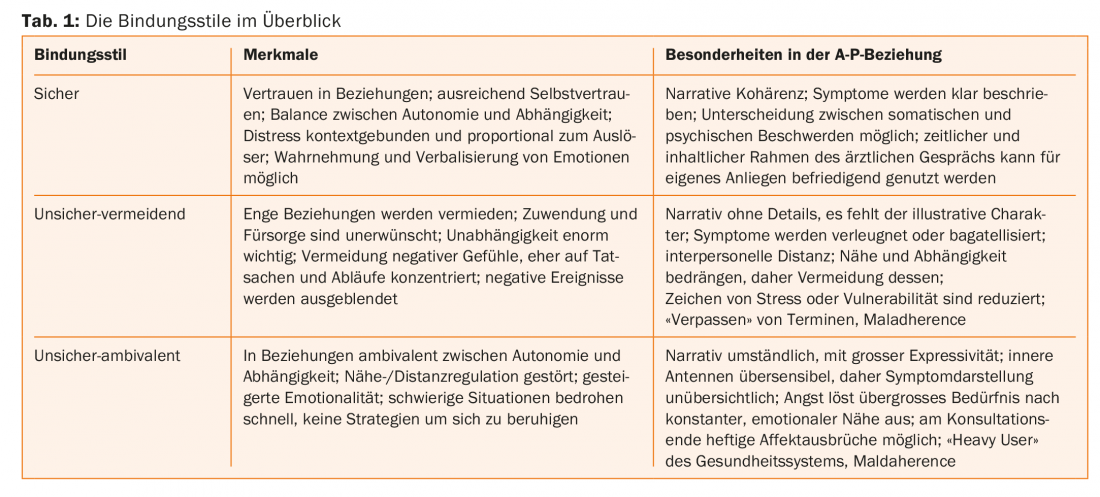

Insecurely attached people are more likely to lack these skills, have reduced stress coping strategies, use more addictive substances as a result, and have fewer stable relationships. In terms of the A-P relationship, patients with insecure attachment style find it difficult (Table 1), present their symptoms in a coherent way; insecure-ambivalent patients tend to give very detailed, circumstantial presentations, insecure-avoidant patients, on the contrary, are conspicuous by a sparse, not very vivid presentation and by omissions of symptoms due to lack of perception; utilization behavior may be above average in insecure-ambivalent or low in insecure-avoidant patients, and finally, medication adherence may be disturbed in the sense of overuse or the opposite [1].

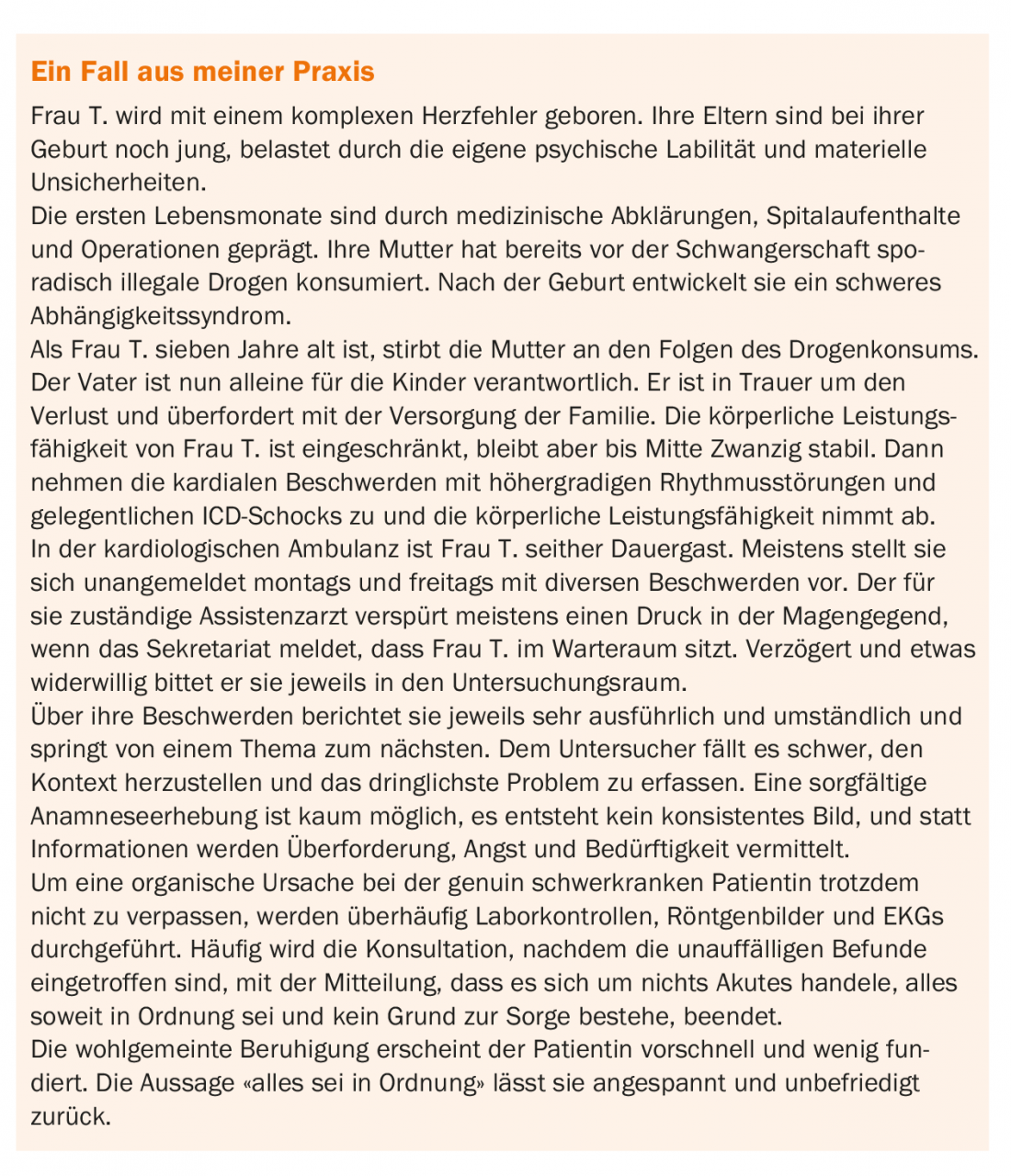

From the perspective of attachment theory, what happened in the A-P relationship in the case described?

The patient’s anxiety level (see box) increases regularly for a variety of reasons. Her ability to calm down is limited and when a certain level is exceeded, she hopes to find reassurance by seeing a doctor. She presents her complaints in an exuberant, exaggerated and vehement manner, shaped by her early childhood experiences of being heard and receiving attention only in this way. Lost in the “jungle” of her somatopsychic sensations, which threaten and frighten her, she reports hastily and without structure, in the unconscious hope of meeting a competent counterpart and finding supportive closeness.

The doctor focuses on clarifying physical symptoms and tries to put them into context. The traditional process of taking a patient’s history and making findings, taking diagnostic measures, and finally making a diagnosis is more difficult in these consultations. It is difficult for the physician to recognize a common thread in the “jungle” of complaints and he has the feeling that his knowledge and measures do not do justice to the (unconscious) concerns of the patient. Knowing about possible, potentially serious complications of this genuinely seriously ill patient, he is anxious to examine carefully and concerned not to miss anything relevant.

First, the patient experiences a reduction of her anxiety through the doctor’s attention. However, the end of the consultation, as a perceived separation from the supposedly more competent counterpart, causes the anxiety level to rise again. Body sensations – as fear equivalents – increase and the unconscious basic assumption stemming from early childhood experiences that their needs are not perceived with sufficient sensitivity by the counterpart is confirmed once again. The diagnostic measures to exclude serious causes and thus to de-anxify fail to achieve their goal and serve at best to reassure the physician. The patient leaves the consultation and a next consultation, of the turning wheel of permanent repetitions, is already in unconscious planning.

From the perspective of attachment theory, there is an overactivated attachment system with an insecure-ambivalent attachment style. Dangers from inside and outside, in the form of unknown bodily sensations or conflictual interpersonal situations, are perceived earlier and more strongly by oversensitive antennae, generate flooding fears and lead to an excessive need for constant, emotional closeness and support by a competent counterpart. Options for independent reassurance are hardly available.

Conclusion

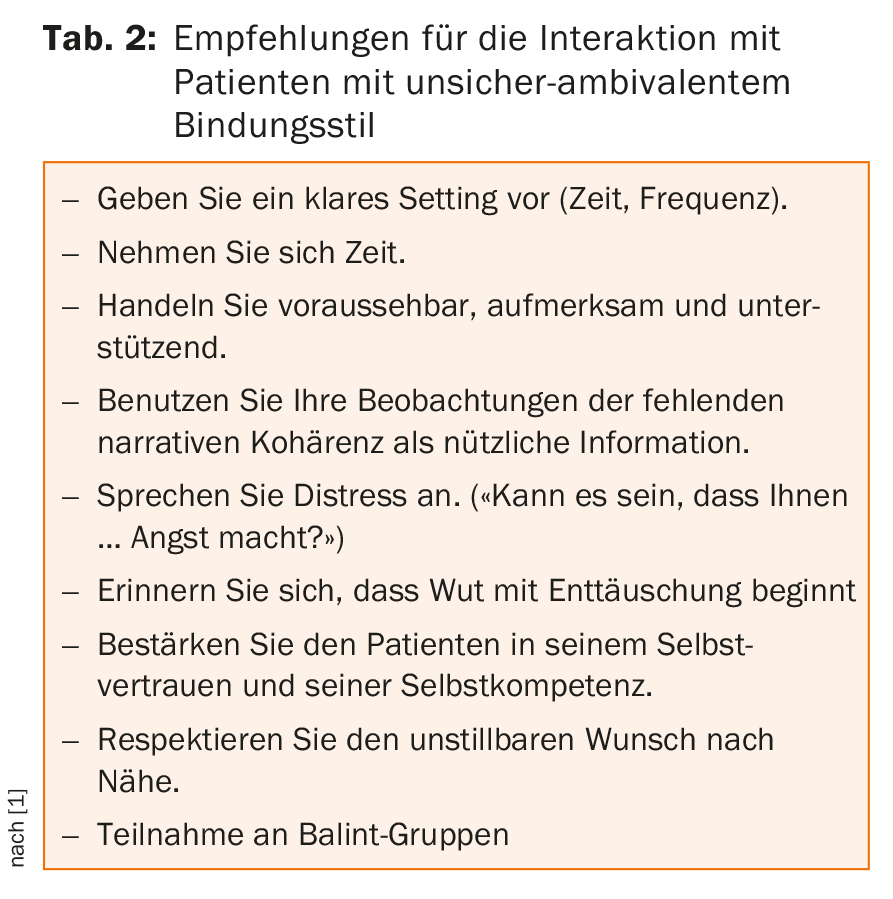

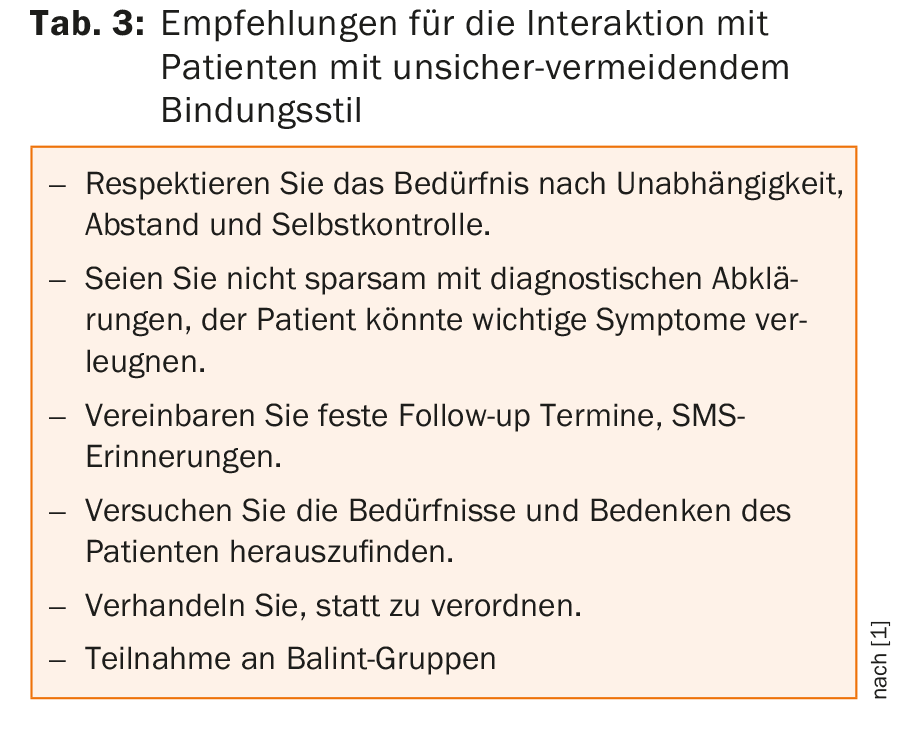

Early childhood experiences with primary attachment figures fundamentally shape our attachment style – throughout our lives. For people with insecure attachment styles, distress may cause reactivation of previous attachment experiences that make them appear either anxious-clingy, or distant-uninvolved. The doctor-patient relationship can thus experience a specific imprint and make additional demands on us practitioners. Established measures to promote a good doctor-patient relationship are therefore all the more relevant; in addition, knowledge of attachment styles can help to increase the quality of the A-P relationship (tables 2 and 3). This has been shown to be the basis for better treatment outcome, increased adherence and greater patient and practitioner satisfaction.

Take-Home Messages

- Keep in mind that when there is fear, weakness, and illness, previous attachment experiences can be activated.

- Consider insecure attachment behaviors in difficult doctor-patient relationships.

- Do not be unsettled.

- “Think of the patient as troubled rather than troubling” [1].

Literature:

- Maunder R, Hunter J: Love, Fear, and Health: How Our Attachments to Others Shape Health and Health Care. University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division; 2015.

- Balint M: The physician, his patient and the disease. 11th edition, Klett-Cotta; 2010.

- Bowlby J: Attachment as a secure base: foundations and application of attachment theory. 3rd ed. Ernst Reinhardt Verlag; 2014.

- Grossmann K, Grossmann KE: Attachment and human development: John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth, and the foundations of attachment theory. 5th edition, Klett-Kotta; 2015.

- Bodenmann G: “Ideally, daycare attendance should not begin until the child is 2 to 3 years old.” Tagesanzeiger, 23.10.2017.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(2): 31-34.