There was a long struggle before outstanding athletic achievements by female athletes received the same recognition as those by male athletes. Since then, the discussion about the comparability of athletic performance between the two sexes has increased. Part of the discussion is the differences in physique between women and men and how these affect performance.

Various publications on the subject of “women and sport” begin by mentioning the earlier difficulties for female athletes to participate in the Olympic Games – the measure of all sporting events in general. The rocky road of women to Olympia is extremely interesting from a historical point of view. This article shall start with the now fundamentally revised eligibility requirements of female athletes. On the occasion of the last Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, medals were awarded in 28 different sports (from B for badminton to V for volleyball), in 27 of which men were “allowed” as participants, and in rhythmic gymnastics the list of participants even consisted exclusively of female gymnasts. So, in a little more than 100 years, the situation has changed radically in terms of admission criteria, even if, from a global perspective, women still face major problems in many countries (developing countries, Islamic states). For example, there are either hardly any sports activities for women or they are not allowed to appear unveiled in public for religious reasons. Joint training with men is often completely taboo. Nevertheless, may be claimed that from a sports medicine perspective, this change clearly shows that the initial, unjustified health concerns have subsided.

However, these sociological transformations by no means imply that women do not exhibit differences in terms of sporting activity compared to men, and it is now necessary to take a closer look at these characteristics.

Physique in gender comparison

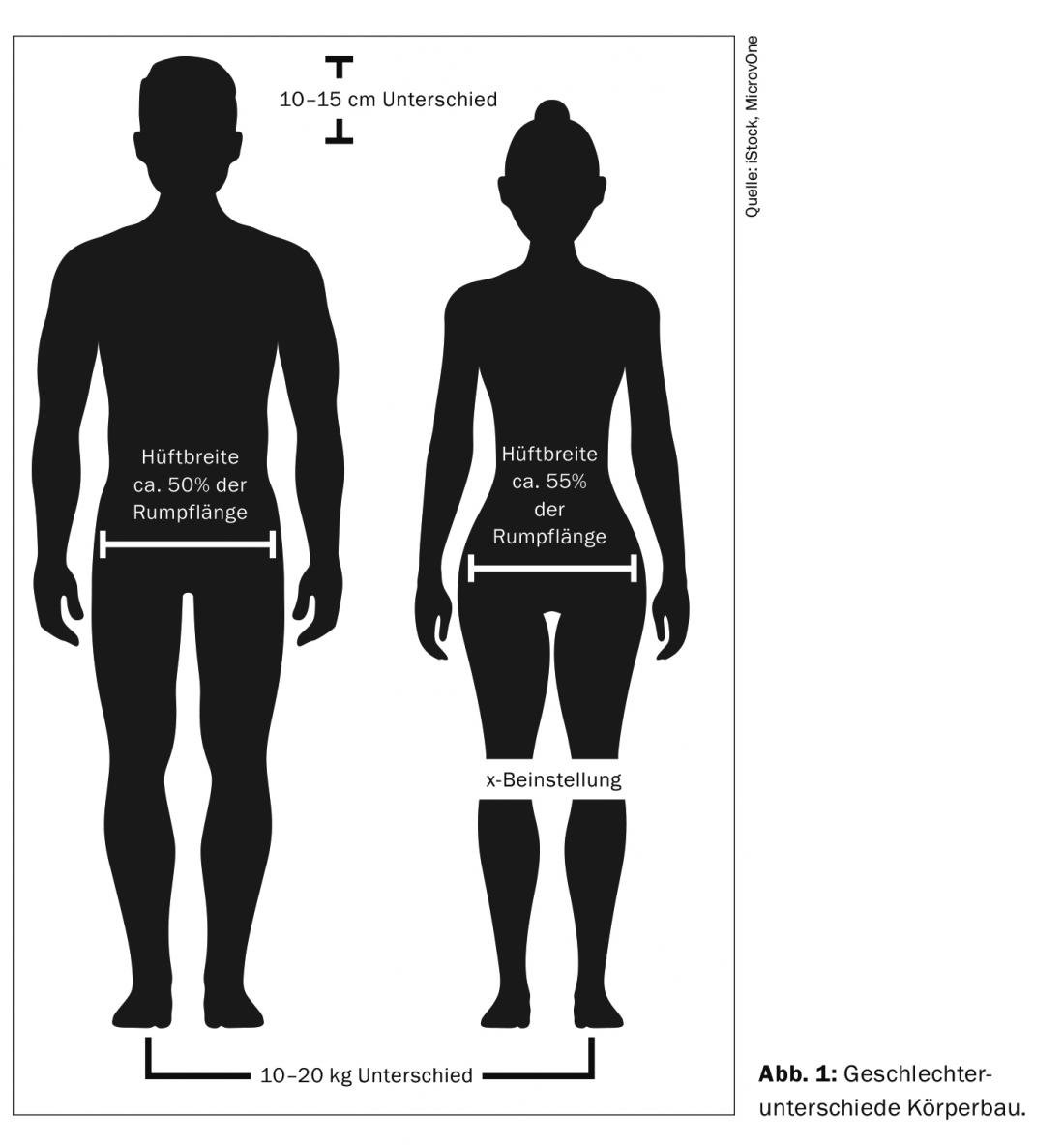

Let us start with the most obvious differences concerning morphology. As is generally known, women and men have characteristic constitutional differences. On average, women are 10-15 cm shorter and 10-20 kg lighter than men. The reason for the smaller size is the hormonally induced faster skeletal maturation and the associated earlier growth plate closure [1]. Also (well) visible is the so-called trunk accentuation of the female sex compared to the extremity accentuation of the male. Compared to the male, the female has shorter extremities and a relatively longer torso. From the morphological point of view, the woman has narrower shoulders than the man, for this she is qualified as pelvic wide. The pelvic width makes up approx. 55% of the torso length, in men this is only about 50% (Fig 1) . This characteristic is important in sports medicine, because this hip width leads compensatorily to a physiological X-B position. Together with the torso tuck, this genoa-valga position favors a downward shift of the body’s center of gravity, which can have a negative effect in sports, especially in the running and jumping disciplines.

Mammae and sport activity

One of the most morphologically obvious differences between male and female are the mammae. This organ plays a central role, also in psychological terms, as an element of self-confidence and body image. But also in the context of sports, where they seem to trigger some problems. Little known from our time is that close to one in five women abstain from physical activity because of their breasts, which are considered a disability. Complaints reported include looks perceived as uncomfortable with large breasts, but also pain [3]. It should be borne in mind here that, depending on the volume, the mammaries, weighing up to 200 g per side, can certainly have an impact on posture. Low back pain with large volume breasts is not uncommon. There are some known cases of reduction plastics in elite sports (the finalist of Roland-Garros 2017, tennis). There may also be more localized pain resulting from the more extensive movements of the organ during physical activity. A recent British study was able to show that the female breast moves significantly more than previously thought, and in all directions, not just up and down [4]. This finding was evident regardless of the size of the breast. Women with small breasts may experience pain during exercise just as busty athletes do. This can be attributed to injuries to the Cooper ligament, the only anatomic suspension system of the mamma. These considerations are closely related to the selection of the chest holder, far from all models are suitable for sports. Not only manufacturers, but also medical specialists recommend taking the same care when choosing a bra suitable for sports as when choosing a running shoe. Indeed, it would be unfortunate if women were discouraged from physical activity, because regular physical activity appears to have a proven protective effect against the development of breast malignancies [5].

In further connection with sports and its influence on breast tissue, direct traumas should be mentioned (blows, safety belts, balls etc). Again, the protection provided by the clothing plays an important role. The resulting hematomas tend to calcify, which can lead to certain difficulties in interpreting mammograms.

The last point to mention is the disturbance of certain hormonal balances by the repeated shocks to the breasts. Depending on whether a sports bra is worn while running, fluctuations in prolactin secretion have been described, and amenorrhea [6] and galactorrhea may also occur in the absence of support. So it is worth asking about such clothing habits in endocrinological disorders in female runners.

Bone structure

If we look at the skeleton in terms of gender differences, we can see that the female gender has a “lighter” bone structure compared to the male gender, combined with a lower degree of mineralization (weight about 25% lighter). As a consequence, weaker mechanical loading capacity is to be expected, which most likely explains the 2-6-fold increased risk of stress fractures [1]. In terms of muscle mass, women have a good 10% less muscle mass than men. It appears that there are also gender differences in muscle fiber composition: muscle fiber type I dominates in females. Also, the muscle fiber cross-sectional area in women is much smaller (15-40%), which ultimately explains why the maximum strength of the female sex is also lower than that of men in a similar proportion. All of these features, compounded by the anatomic and hormonal influences already discussed, explain the nearly 10-fold increased risk of injury for anterior cruciate ligament ruptures [2]. As a last point, it is necessary to mention the more generous fat depot of women compared to men. The difference is about 10% [7]. This factor, combined with the lighter skeleton, gives the female a lower body density, which, in combination with the pelvic anatomy, the lower position of the body’s center of gravity and the greater torso length, is responsible for advantages in terms of swimming position.

You can read part 2 of this article in issue 10 of HAUSARZT PRAXIS.

Literature:

- Neumann G, Buhl H: Biological performance prerequisites and exercise physiology aspects in trained women. Med Sport 1981; 21: 154-160.

- Weineck J.: Sports biology. Spitta Publishing House 2004

- Burnett E, et al: The Influence of the Breast on Physical Activity Participation in Females. J Phys Act Health 2015; 12(4): 588-594.

- Risius D, et al: Multiplanar breast kinematics during different exercise modalitites. Eur J Sport Sci 2015; 15(2): 111-117.

- Lynch BM, et al: Physical acitivity and breast cancer prevention. Recent Results Cancer Res 2011; 186: 13-42.

- Prior J, et al: Prolactin changes with exercise vary with breast motion: analysis of running versus cycling. Fertility and Sterility 1981; 36:268.

- Tomasists J, Haber P.: Performance physiology, textbook for sports and physiotherapists and coaches. Sprinter Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2016.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(9): 6-8