DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS already contained several articles on the epidemiology, clinic, modern diagnostics and therapy of food allergies as well as food intolerances [1–7]. This article briefly reviews the history of food allergies over the past 100 years. In the following, some milestones for the diagnosis of food allergies will be discussed and the phenomenon of lethal food allergies, which has been known since the 1980s, will be addressed. A second part on rare trigger pathways and oral desensitization will appear in the next issue of this journal.

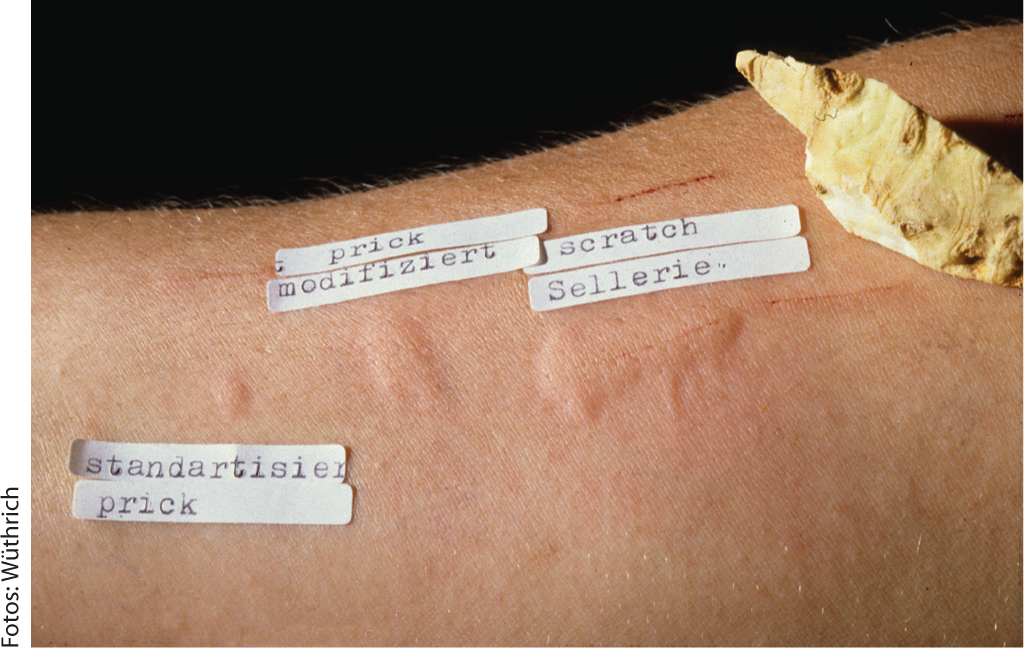

The first scientifically proven notification of a food allergy did not occur until the beginning of the 20th century: In 1912, the American pediatrician Oscar Menderson Schloss (1882-1952) was the first to confirm the alimentary genesis of certain allergies with the help of skin tests. He was able to trace a case of food allergy to the consumption of egg: a scarification test (scratch test) with hen’s egg white was positive. He also succeeded in testing partial fractions of the protein in isolation and found that ovomucoid, along with ovoglobulin and ovomucin, caused the most severe allergic skin reactions. In addition, he also tested oatmeal and almonds. This work is a landmark in the history of allergy and after the appearance of another publication, the scratch test, originally used by Blackley in 1873 to detect pollen allergy, became the routine method for detecting food allergy (Fig. 2). Help the intracutaneous test, which was introduced in 1908 by Mendel and Mantoux as the tuberculin test, Karl Prausnitz (1876-1963) and Heinz Küstner (1897-1963) succeeded in 1921 in passively transmitting a fish allergy by means of serum from the allergic person. However, it was soon recognized that intradermal tests with foods can be false-negative, either because the skin is not the shock organ or because the relevant allergens are denatured by the extract preparation. Some authors have pointed out that only fermentative degradation products have an allergizing effect. Interesting was the finding of a so-called “catamnestic skin reaction” by Max Werner (1911-1987). According to the latter, intradermal samples with food allergens turn out positive only after their ten- to 14-day abstinence, an observation confirmed by other authors. The modified prick test was developed by Helmtraut Ebruster and published in 1959, again initially with inhalation allergens. Due to the findings since the 1970s that skin tests with commercial extracts from fruits and vegetables are more often false-negative, the prick-to-prick test method has been increasingly used for testing these allergens – in addition to scratch tests with native material. The prick test needle is inserted directly into the fresh fruit or fruit varieties, and the prick test is then performed with the same test needle (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2: Failure of skin tests with standardized prick test, with prick-to-prick test and with scratch tests with celery tuber.

Fig. 3: Prick to prick test with jackfruit

Alternative test methods before the detection of IgE

Since cutaneous testing with alimentary allergies often failed (false-negative and false-positive test results), other, not always reliable, test methods were used – in addition to re-exposure tests – such as pulse rate increase after food exposure (after Coca), leukopenic index, basophil drop, platelet fall test (Fig.4), or – in case of exclusive gastrointestinal symptomatology – the elaborate, targeted exposure samples on the small intestine under radiological control, among others, are suggested. The “leucocytotoxic test” (Bryan’s test) developed by Black and Bryan towards the end of the 1950s for the detection of allergies to foods and additives is based on the microscopic estimation of activation-induced changes and autolysis of leucocytes after mixing blood with allergens and food extracts. The test was denied approval in the U.S. due to its inability to detect allergies. The Antigen Leukocyte Cellular Antibody Test (ALCAT) or leukocyte activation test, which is still touted today as a diagnostic method for qualitatively determining food intolerances, is ultimately a further development of Bryan’s test. Its use is unanimously declared by many national and international allergy societies as unsuitable for the clarification or exclusion of a food allergy.

Diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergies

The discovery of IgE as a new class of immunoglobulins with reagin activity and the development of sensitive, quantitative in vitro methods, such as the “radio-immunosorbent assay” for the determination of total IgE concentration in serum or the radio-allergo-sorbent test (RAST) for the detection of circulating serum antibodies with IgE specificity [8], has undoubtedly represented a major advance for routine allergological diagnostics, including food allergies, and for research into their pathogenesis. When highly purified fish allergen extracts were used in children with allergic manifestations after consumption of cod, 100% agreement was found between history or RAST and skin test. Gradually, the range of foods available for IgE determination has expanded, but it has also been recognized that there are certain limits to the diagnostic value of a RAST – as well as the skin test. Positive IgE detection is only an expression of sensitization to the food tested, and not evidence that an allergic reaction is triggered upon exposure to the food. Conversely, a lack of detection of serum IgE antibodies by the RAST method or other modifications, such as ImmunoCAP FEIA (Fluor Enzyme Immuno Assay), does not exclude a food as the causative agent of allergic symptomatology due to the often poor quality of diagnostic extracts. Many food extracts are biologically unstandardized or insufficiently standardized. Degradation of allergenic proteins during the extraction process is a common phenomenon, resulting in the relevant allergens being absent or insufficiently present in the extract. On the other hand, similar molecular structures in food and inhalant allergens (pollen, dust mites, latex, etc.) lead to multiple positive results in skin and IgE tests due to cross-reacting IgE antibodies.

The component-based diagnostics

A promising approach to distinguish cross-allergies from genuine co-sensitizations with possible therapeutic consequences is represented by the “recombinant allergens” available for the ImmunoCAP system (Phadia). Component-based diagnostics, i.e., the use of IgE determinations against food-specific marker proteins, helps explain clinical reactions and identify irrelevant sensitizations [3, 5]. Likewise, allergological research in recent years has sought to identify “marker” allergens that are pathognomonic for certain clinical pictures, e.g. wheat-dependent, effort-induced anaphylaxis (see below). Recently, the Immuno Solid-phase Allergen Chip (ISAC) has become available as a pioneering test system in the field of in vitro diagnostics, enabling the analysis of an almost unlimited number of allergen components in a single analytical step. ISAC technology allows the determination of all relevant allergens in a single analytical step from a very small amount of patient serum. Because of the abundance of results and the relatively high cost, the indication of an ISAC determination should be made only by the allergist or a physician with special knowledge in this field.

The double-blind, placebo-controlled oral provocation…

Oral exposure tests are therefore often the decisive diagnostic measure to provide evidence of a current food allergy or intolerance. The so-called double-blind, placebo-controlled food provocation (DBPCFC) is considered the only scientifically accepted evidence of food allergy/intolerance. Even though DBPCFC represents the golden standard for clinical studies, this complex procedure can only be used in routine diagnostics of food allergy selectively in allergy centers, since provocation tests always include the risk of triggering severe reactions.

Lethal food allergies

Already in 1926 a fatal reaction after food provocation was published. It involved an 18 -month-old infant with atopic eczema and a history of three episodes of generalized allergic reactions after eating a few spoonfuls of a pea porridge. Under inpatient conditions in a pediatric ward, oral provocation with a carrot/pea porridge was performed by the head nurse on the order of the senior physician, during the lunch break. Immediately following the test meal, the child developed angioedema, cyanosis, and circulatory collapse. He died despite intensive emergency treatment.

The first case of a spontaneous fatal allergic food reaction was published only 25 years ago, involving a 24-year-old woman with known peanut allergy after eating a cake. The Canadian patient had repeatedly purchased a hazelnut cake with marzipan (almond icing) at the same bakery and endured it without reaction. Shortly after eating only a few bites of the pastry, a severe allergic reaction suddenly occurred one day, resulting in death by asphyxiation. Forensic clarification of the extraordinary case revealed that the paste used to make the glaze now contained “arachides”; this term for “peanuts” was not recognized by the English-speaking baker.

Lethal or life-threatening allergic reactions to food in infants and children, but especially in adolescents and adults, are unfortunately no longer rare today. Since the late 1990s of the previous century, case series of fatal food allergies, mostly after ingestion of “hidden” food allergens, most commonly peanuts, various types of nuts, such as Brazil nut and cashew nut, but also milk, egg, fish, and shellfish (lobster, shrimp), have been repeatedly reported from the United States, and later from various countries. The lay press also regularly announces such deaths. It is estimated that approximately 120 deaths occur annually in the United States due to anaphylactic reactions to food.

The hidden presence of food allergens, e.g. peanut allergens as peanut paste in sweets and chocolate, makes it difficult or even impossible to achieve abstinence – despite improved declaration requirements for intermediate products.

The tragic death of a 16-year-old Swiss girl who bought roasted almonds – as she believed – from a stall on Tower Bridge in London, but which were actually peanuts to which she was allergic, was referred to in an earlier editorial [2].

Literature:

- Wüthrich B: Food allergies. Rarer than patients think. DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2012; 2: 16-20 .

- Wüthrich B: “Lucia died a tragic death” – Food allergies can be fatal. (Editorial). DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2010; 2: 1.

- Wüthrich B: Component-based diagnostics. Recombinant allergens for the clarification of food allergies. DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2010; 2: 11-15.

- Wüthrich B: What is your diagnosis? (Quiz): status after single allergic reaction with Quincke’s oedema (lips, tongue, hands) to crustaceans. DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2011; 3: 38 and 42.

- Borelli S, Wüthrich B: Component-based diagnostics. Use of recombinant allergens. DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2012; 2: 22-24.

- Wüthrich B: What is your diagnosis? (Quiz): Food-induced exertion-induced anaphylaxis with severe sensitization to cereal proteins, especially to rTri α19-omega-5-gliadin. DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2013; 1: 25 and 32-33.

- Wüthrich B: The histamine intolerance syndrome. Headaches, sneezing attacks and co. caused by biogenic amines. DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2011; 2: 4-8 .

- Wide L, et al: Diagnosis of allergy by an in vitro test for allergen antibodies. Lancet 1967; 2: 1105-1107.

- Storck H, et al: Platelet drop as an aid to allergy diagnosis, in: Grumbach AS, Rivkine A (eds.): First International Congress for Allergy. Karger: Basel, New York 1952: 739-744.

- Bergmann KC, et al: Illustrated history of allergology. Dustri-Verlag Dr. Karl Feistle 2003: 102-103.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2013, ed. 4: 4-6