The presence of ILD in rheumatoid arthritis patients:in limits prognosis and survival as well as quality of life. Early diagnosis is of great importance so that treatment can be started in time and prognostically relevant progression can be prevented. Acute exacerbations of ILD can further complicate the course. These are either associated with disease progression or triggered secondarily by infections.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is most common in collagenoses, especially systemic sclerosis (SSc), autoimmune myopathies, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and also rheumatoid arthritis (RA). During the clinical, rheumatologic assessment, the affected person should always be asked about the possible presence of respiratory limitation. The presence of ILD in rheumatoid arthritis patients:in limits prognosis and survival as well as quality of life [1]. Early diagnosis is of great importance so that treatment can be started in time and prognostically relevant progression can be prevented. Progression of ILD is common and is observed to a relevant extent, particularly in SSc and RA patients:in; criteria for determining progression have recently been published for this purpose [2]. Acute exacerbations of ILD can further complicate the course. These are either associated with disease progression or triggered secondarily by infections.

ILD Board

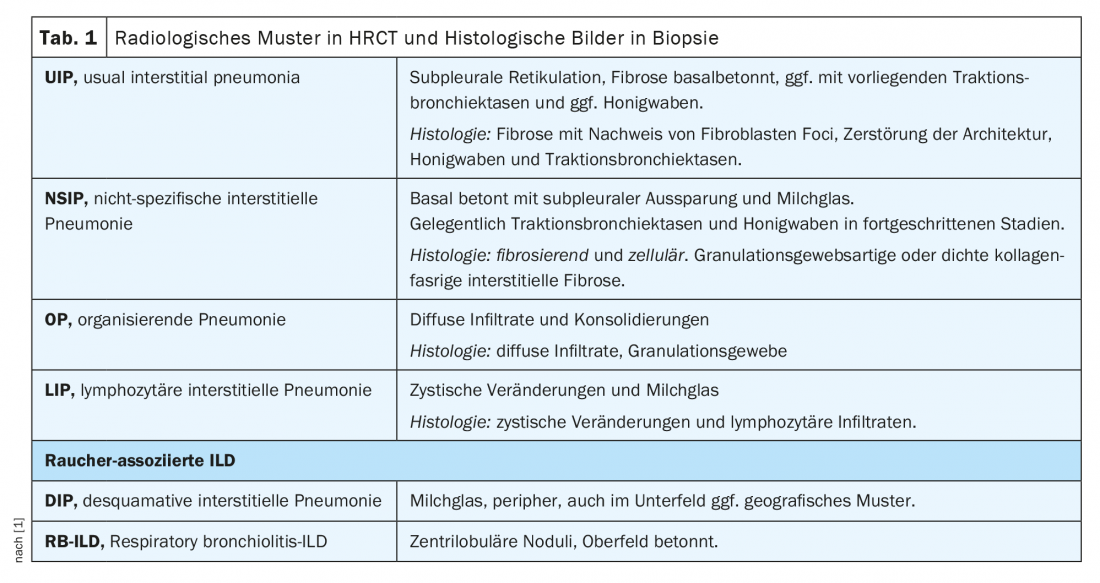

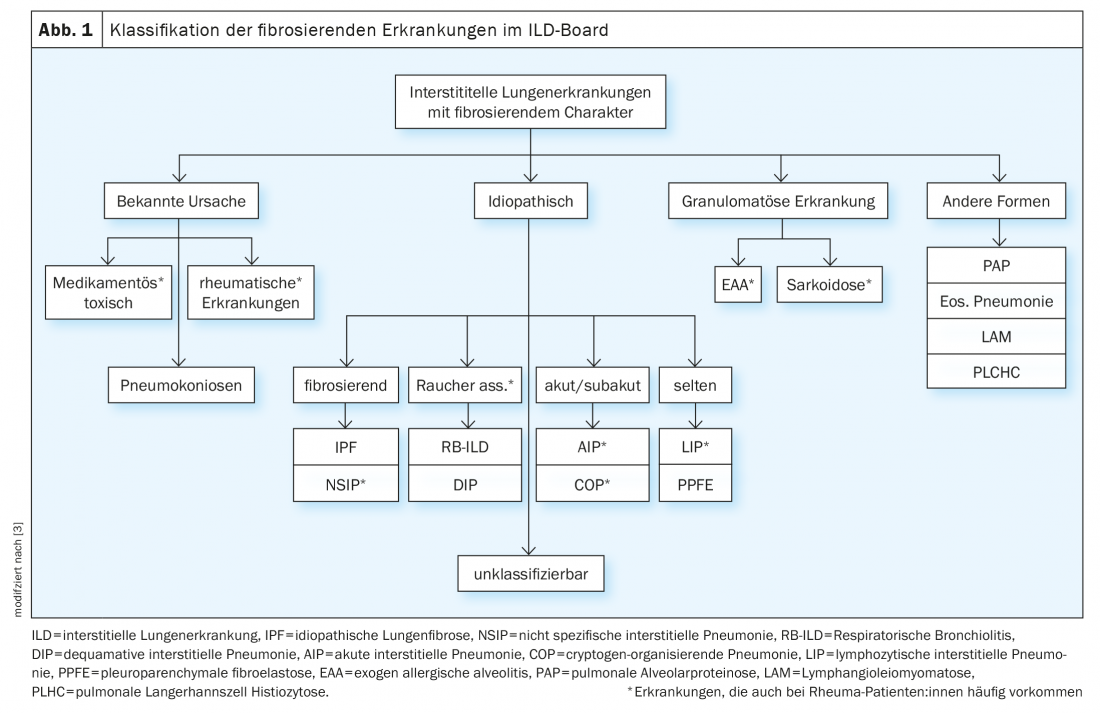

Within the ILD board, cases are discussed in an interdisciplinary manner based on the following parameters: leading symptoms, history incl. Exposures and noxious agents, immune serology, pulmonary functional limitation in body plethysmography (esp. FVC, TLC, FEV1) and diffusion capacity (DLCO), imaging by high-resolution computed tomography of the thorax (HRCT), and results of invasive diagnostics by bronchoscopy incl. Microbiology, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) findings, and histologic findings from biopsies. (Table 1). However, rheumatoid patients can develop ILD not only due to the rheumatic disease, but also due to noxae, drugs or exposures (especially in lymphocytic BAL) etc. (Fig. 1). It should be noted that obtaining biopsies is rarely strictly indicated in confirmed rheumatic diseases, but it serves to simplify the delineation of differential diagnosis, especially in vasculitides and especially the coexistence of tumorous and other diseases.

Inflammatory rheumatic diseases with possible ILD involvement.

RA-ILD: RA is the most common rheumatic disease. The presence of arthritides, especially in small joints, as well as elevated rheumatoid factors and antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides (so-called seropositivity) simplify the diagnosis and are accordingly indicative [4]. The most common extra-articular manifestation of RA is ILD, which is seen in 25-60% of RA patients:in HRCT and is responsible for 10-20% of deaths in RA. RA-ILD becomes clinically relevant in approximately 10% of affected individuals. In 10% of cases, pulmonary involvement even precedes the development of arthritis [5]. Risk factors for developing ILD include male sex, smoking, and seropositivity. Imaging most commonly reveals a UIP pattern. Mutations such as in the promoter of the MUC5B gene have been described in the literature. Smoking may additionally aggravate the pulmonary situation. The presence of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) is associated with a dramatically worse prognosis. Differentially, drug-toxic ILD under immunosuppression should be considered. However, methotrexate (MTX)-associated ILD is extremely rare (estimated at 0.1%); in fact, a protective effect of MTX has been described.

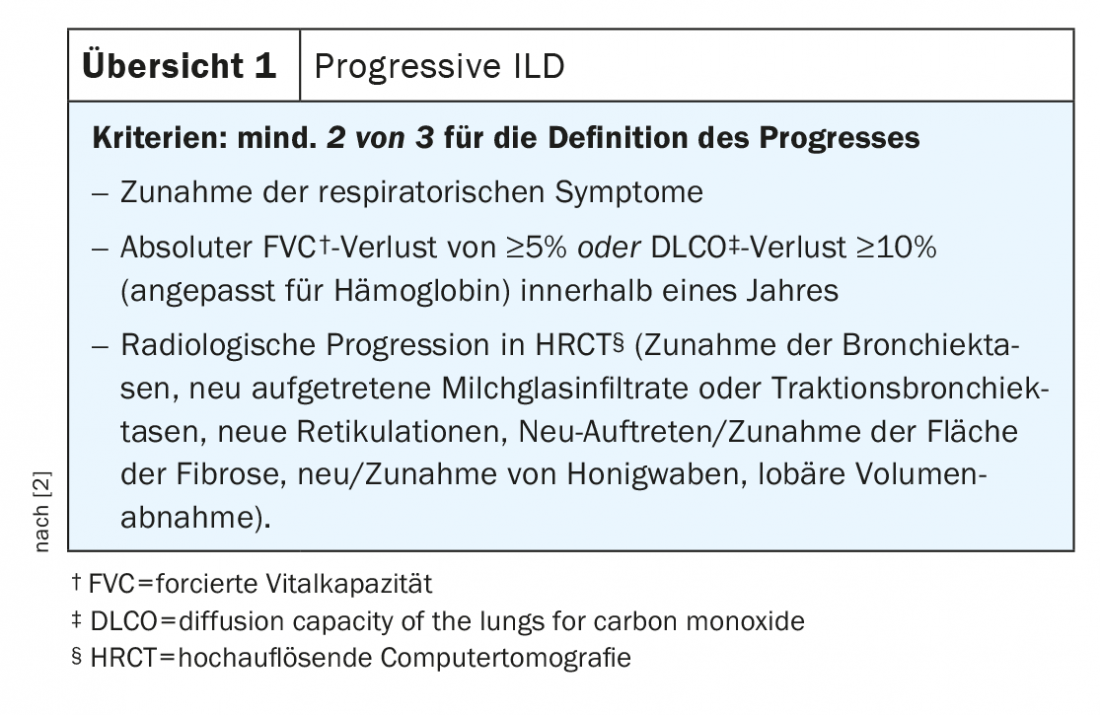

MTX should therefore not be discontinued in RA-ILD. Treatment of RA-ILD is primarily by optimizing immunosuppression. Randomized controlled trials for the treatment of RA-ILD are lacking. The best evidence supports treatment of RA patients:in with concomitant ILD with abatacept and rituximab [6]. Results from the APRIL (abatacept in RA-ILD) trial are pending. In addition, efficacy of JAK inhibitors or IL-6 blockers in RA-ILD has been reported recently in case series [7]. In progressive courses (review 1), initiation of antifibrotic therapy is recommended. For this purpose, nintedanib is approved in the EU based on the results of the INBUILD trial [8]. The overall prognosis of patients:in with RA-ILD is significantly limited with a median survival of approximately three years [1].

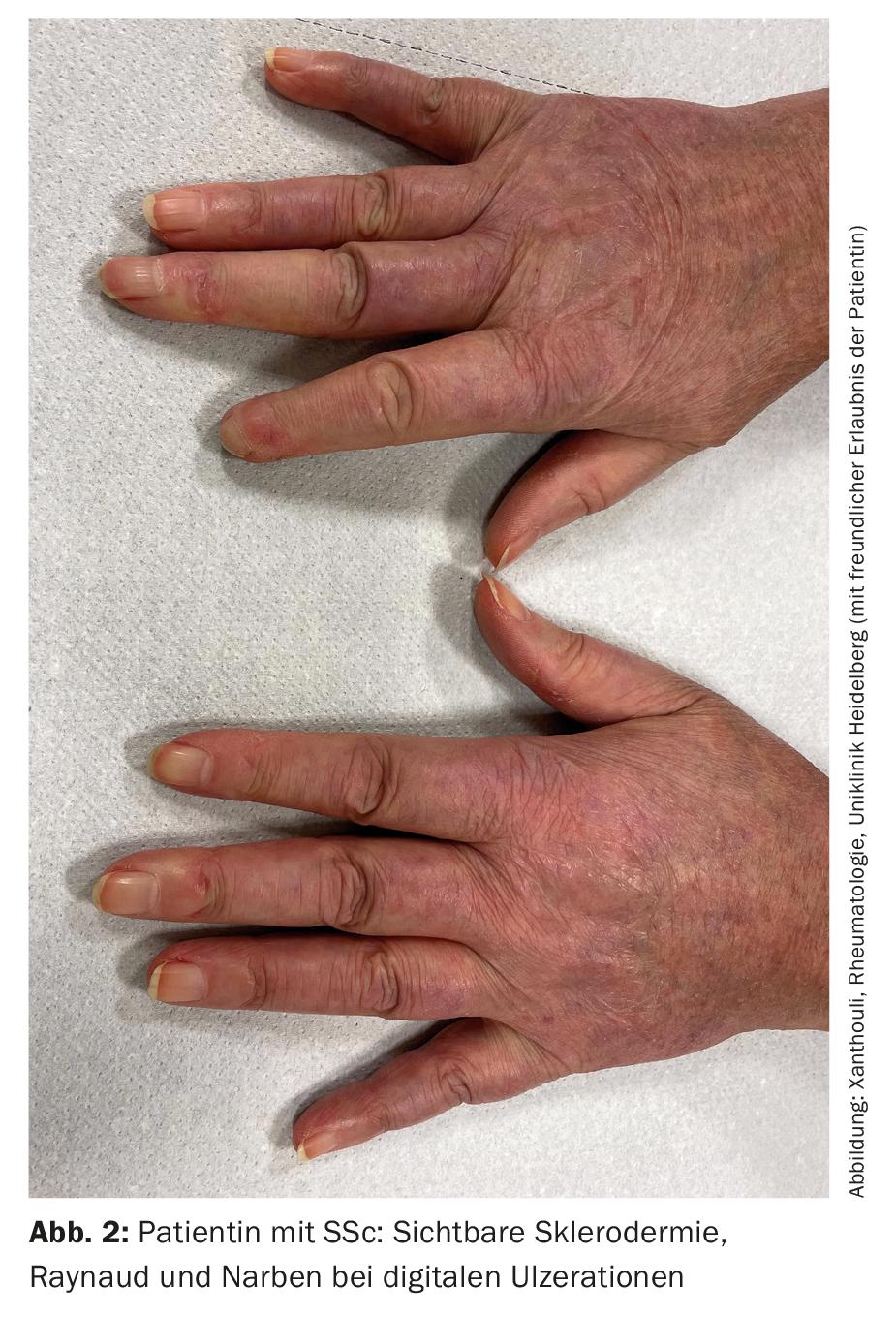

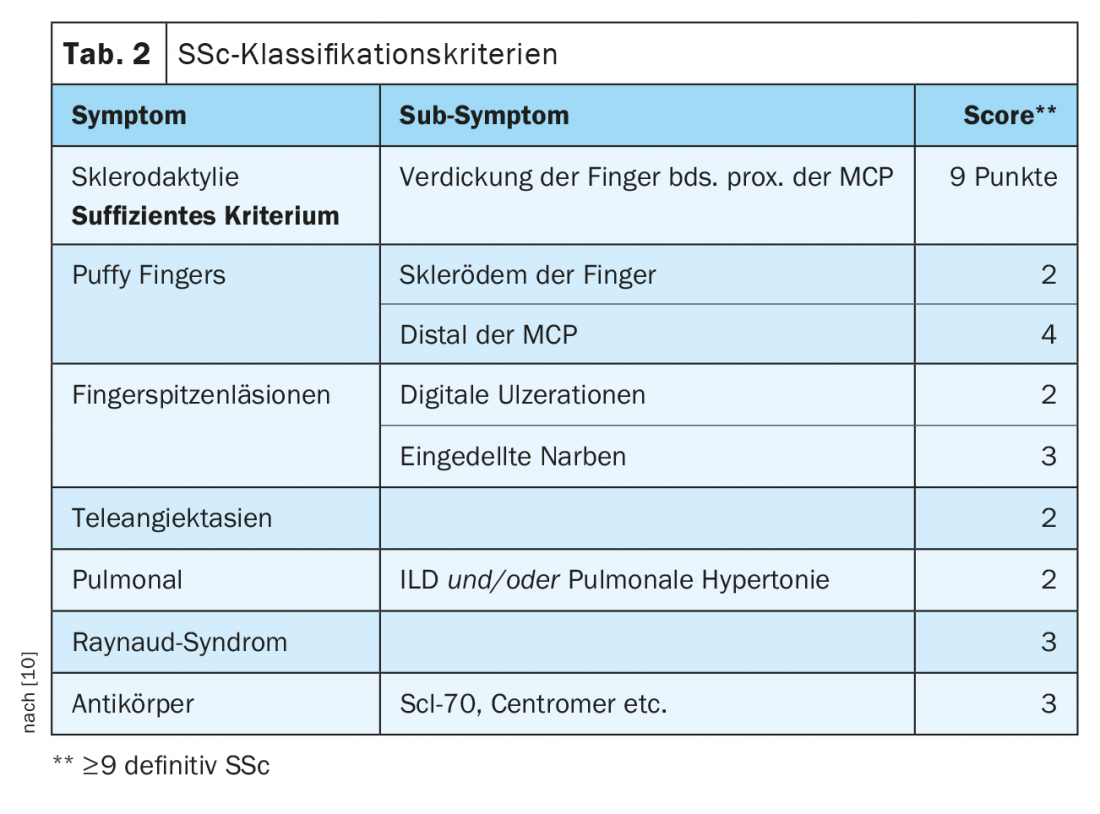

SSc-ILD: Approximately 50-85% of patients with SSc already have interstitial lung changes at initial diagnosis. In 20-30% of cases, this is progressive in the course. ILD currently represents the leading cause of death in SSc patients:in, with a 10-year mortality of approximately 40% [1]. Early correct diagnosis as well as recognition of ILD are prognostically relevant [9]. Classification criteria have been established to simplify diagnosis (Table 2) [10]. Sclerodactyly, digital ulcerations, Raynaud’s symptoms, and microstomia are clinical signs that should immediately suggest SSc (Fig. 2). The development and especially the progression of the disease occur predominantly during the first three years of disease. Frequently, ILD is asymptomatic in SSc. Recommended to initiate screening by HRCT at initial diagnosis of SSc. Pulmonary function tests (body plethysmography and diffusion capacity measurements) are required quarterly to semi-annually. Risk factors for developing ILD include male sex, the presence of diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, evidence of autoantibodies to Scl-70, and African American ancestry [11]. Reflux, diffuse skin involvement (and thus a higher modified Rodnan Skin Score), and male sex are risk factors for rapid progression of ILD. In CT, an NSIP pattern is most frequently present, and a UIP pattern is found less frequently.

Treatment is primarily immunomodulatory and adjunctive antifibrotic [1]. Based on the results of the SLS-I and -II trials, therapy with cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil can be initiated in SSc-ILD [12,13]. In the FocuSSed study, there was improvement FVC in the inflammatory SSc phenotype with tocilizumab (antibody against IL-6 receptor). Tocilizumab has therefore received FDA approval for the indication SSc-ILD, but is still used off label in Europe [14]. For rituximab (also still off label), good data are currently available for the treatment of SSc-ILD from the DESIRES trial [15]; final results from the RECITAL trial are pending. The SCENCIS study is the first, largest, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of nintedanib antifibrotic therapy in patients:in with SSc-ILD [16]. Nintedanib is FDA-approved for the treatment of SSc-ILD, but is effective only in preventing progression of lung involvement and is not suitable for the treatment of other SSc manifestations.

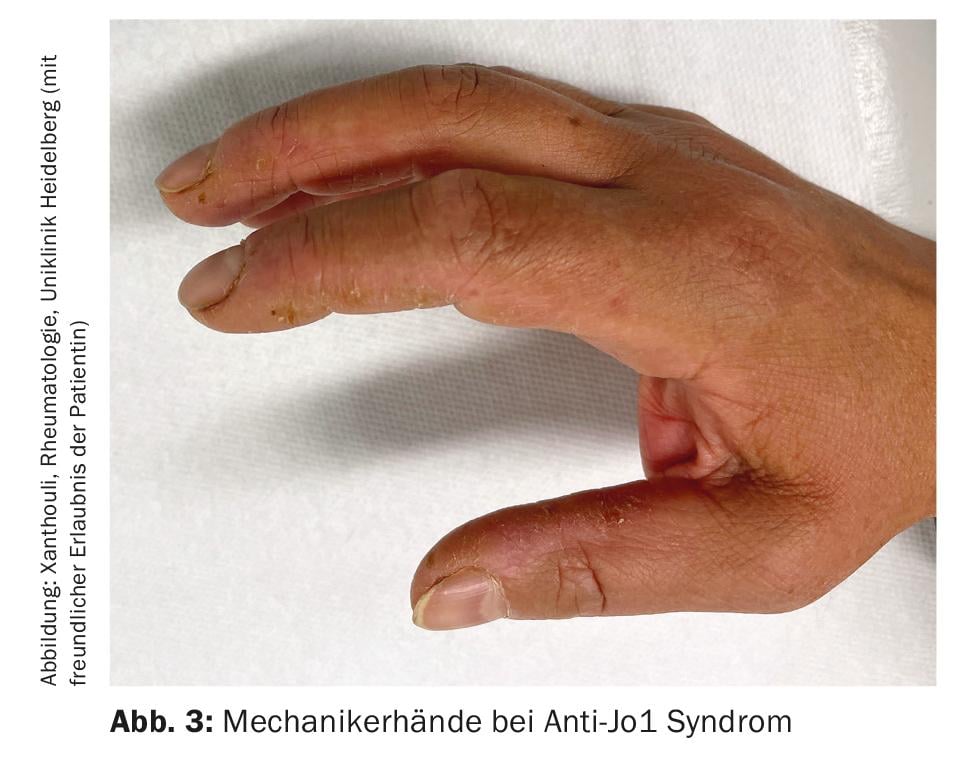

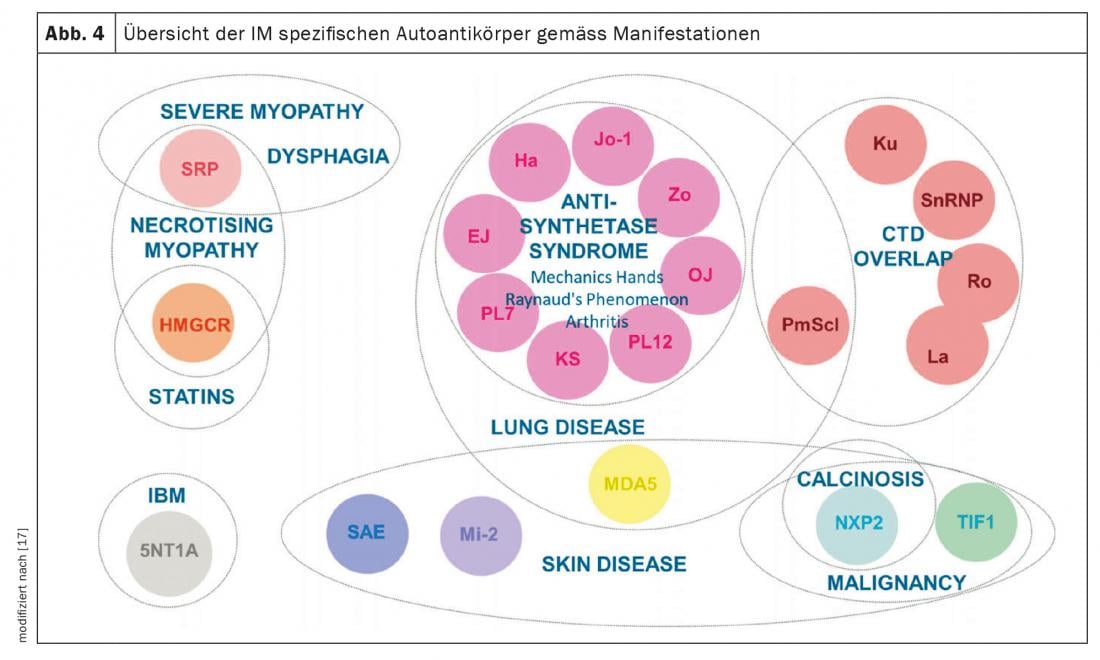

Inflammatory myositis (IM): IM includes antisynthetase syndrome (ASD), dermatomyositis, polymyositis, inclusion body myositis, and overlap syndromes with other collagenoses. These manifest with and without muscle involvement (myositis). Patients with muscle involvement have exceptionally high muscle levels in the blood (CK, creatine kinase) and show pathological signals in muscle MRI and neurophysiological examination. Other clinical manifestations suggestive of IM include mechanic’s hands (Fig. 3) especially in anti-synthetase syndrome, arthritides, heliotropic exanthema in dermatomyositis, and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Up to 70% of patients with ASA develop ILD. Furthermore, ILD is the initial manifestation of the disease in one-third of those with IM [7]. The most common autoantibodies in ASA are those against Jo-1, however other antibodies e.g. against PL12, PL7, Mi2 etc. are known and should be determined if symptoms are typical. Detection of MDA5 (melanoma differentiation accociated protein 5) antibodiesin unclear lung involvement indicates a rapidly progressive, refractory course associated with higher mortality, often without myositis. The association between malignancies and IM should be noted. This is particularly high for detection of TIFγ and NXP2 antibodies. Here, a malignancy is present in 30% of cases, which is why thorough tumor screening is essential (Fig. 4) [17].

Treatment is primarily with high-dose steroids with good response especially in younger patients:in, sufferers with OP, elevated CK levels and milk glass infiltrates on HRCT. In severe cases, initiation of cyclophosphamide pulse therapy should be considered. Treatment with mycophenolate, rituximab, tacrolimus, abatacept, and JAK inhibitors remains off label, although these are supported by good results from retrospective studies [18]. It is also worth noting that there is an approval for the administration of intravenous immunoglobulins in myositis in the EU [19]. Patients:in with Jo-1 antibodies and evidence of anti-Ro-52 antibodies recently showed a good response to rituximab with respect to ILD involvement, and therefore it should be considered as a treatment option [20].

SLE: The multifaceted pulmonary manifestations of SLE often lead to delayed diagnosis. Up to 12% of those affected could develop ILD during the course of the disease. A particularly dangerous manifestation of SLE is pulmonary hemorrhagic syndrome with severe hemoptysis and rapid respiratory deterioration. In contrast, severe dyspnea, a restrictive ventilatory disorder with diaphragmatic apraxia without the presence of ILD raise suspicion of the presence of a difficult-to-treat shrinking lung syndrome. Initiating chest ultrasonography, measuring respiratory muscle strength, and spiroergometry may lead the way accordingly. Treatment of ILD in SLE is primarily by intensification of immunosuppression. Antifibrotic agents could be used in case of progression – in rare cases; an approval for this is available for nintedanib in the EU [21].

Sjögren’s syndrome: Although the majority of Sjögren’s patients hardly express any pulmonary symptoms, in some cases a restrictive ventilation disorder is found in the lung function diagnosis. The presence of objectifiable sicca symptoms with positive SSA antibodies is crucial for the diagnosis of the underlying disease [22]. In 15% of cases, a LIP pattern with diffuse bipulmonary cystic changes with milk glass is present on HRCT. Bioptically, a lymphocytic infiltrate is visualized. Lymphoma should be considered as a differential diagnosis in cases of unclear intrathoracic masses in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Early diagnosis of Sjögren’s-associated ILD is prognostically relevant with a 5-year survival of 88.5% [23].

Interstitial Pneumonia with Autoimmune Features (IPAF): ILD patients with abnormal antinuclear antibodies (ANA) often present to rheumatologists. In 10-20% of cases, these are incidental findings during ILD screening diagnostics. In HRCT, an NSIP pattern is most commonly present and affected individuals benefit significantly from steroids. However, other indicative symptoms of an inflammatory, rheumatic disease are rarely present. In this case, combined care with a pulmonologist and rheumatologist is necessary to identify a late manifestation of inflammatory rheumatic disease in a timely manner [7].

Other diseases

Vasculitides: In patients:in with granulomatosis with polyangititis (GPA), intrapulmonary granumolomas can often be detected. ILD may develop in rare cases. In contrast, when antibodies to myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA) are detected, ILD with a predominantly UIP pattern is often described. In this case, a complementary diagnosis with regard to other organ manifestations should be made.

Mixed collagenosis: The incidence of ILD is reported to be highly variable at 47-78%. Affected individuals have positive ANA and U1 RNP antibodies. On HRCT, either an NSIP pattern, a UIP pattern, or infiltrates in the sense of OP may be present. Treatment is primarily with immunomodulatory agents [7].

Other non-pharmacological and prophylactic treatment

All patients with rheumatic diseases should receive the recommended vaccinations, especially against COVID-19, influenza and pneumococcus, and refresh them regularly. In advanced stages of ILD, respiratory failure may occur. Oxygen supplementation is frequently required during the course, beginning with exercise and possibly later at rest. For this purpose, a titration is usually performed to determine the dose. Rehabilitative measures such as pulmonary and rheumatic sports as well as inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation measures improve the clinical situation and oxygen uptake of sufferers with inflammatory rheumatic diseases and are still recommended. If therapeutic options are exhausted, listing for lung transplantation should be considered. There are no clear guidelines for the exact timing of the presentation for listing. In SSc, autologous stem cell transplantation is gaining increasing importance, especially in severe clinical courses [24]. If transplantation is not an option, consider initiating palliative and symptom-relieving measures [25].

Summary

Rheumatic diseases can manifest in the lung parenchyma and lead to the development of interstitial lung disease (ILD) here, among other symptoms. Pulmonary manifestations may precede the underlying rheumatic disease in approximately 10% of cases. Therefore, rheumatologists are involved in the interdisciplinary ILD board to contribute in the differential diagnosis and determination of the therapeutic algorithm. The prognosis of rheumatoid ILD is limited, and collaboration between rheumatology and pulmonology practitioners can significantly improve the quality of care. Although the pathogenesis of ILD development remains unclear, the development of drug therapies for rheumatoid ILD is progressing. Both the rheumatologist and pulmonologist should have sound knowledge and confidence in the use of immunomodulatory and antifibrotic agents.

Take-Home Messages

- Inflammatory rheumatic diseases may manifest in the lung parenchyma.

- There is a need for close cooperation between pulmonologists and rheumatologists for diagnosis and treatment.

- Treatment is primarily immunosuppressive.

- Since 2020, the antifibrotic agent nintedanib has been approved for the treatment of SSc-ILD based on the results of the SENSCIS trial. The drug is also used for the treatment of progressive ILD (INBUILD study).

Literature:

- Wijsenbeek M, Cottin V: Spectrum of Fibrotic Lung Diseases. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 958-968; doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2005230.

- Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L et al: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 205: e18-e47; doi: 10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST.

- Kreuter M, Ladner UM, Costabel U, et al: The Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2021; 118; doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0018.

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al: 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69: 1580-1588; doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138461.

- Duarte AC, Porter JC, Leandro MJ: The lung in a cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients-an overview of different types of involvement and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019; 58: 2031-2038; doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez177.

- Mena-Vázquez N, Rojas-Gimenez M, Romero-Barco CM, et al: Predictors of Progression and Mortality in Patients with Prevalent Rheumatoid Arthritis and Interstitial Lung Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med 2021; 10(4): 874.

- Bastian HKA: Lung – Interstitial lung diseases. Act Rheumatol 2021; 46: 544-551.

- Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, et al: Nintedanib in Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1718-1727; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908681.

- Xanthouli P, Hermann W, Hunzelmann N, et al: Scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease. The Pulmonologist 2018; 15: 383-395.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al: 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 1747-1755; doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204424.

- Distler O, Volkmann ER, Hoffmann-Vold AM, et al: Current and future perspectives on management of systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2019; 15: 1009-1017; doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2020.1668269.

- Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, et al: Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 2655-2666; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120.

- Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, et al: Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 708-719; doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30152-7.

- Khanna D, Lin CJF, Furst DE, et al: Tocilizumab in systemic sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8(10): 963-974.

- Ebata S, Yoshizaki A, Oba K, et al: Safety and efficacy of rituximab in systemic sclerosis (DESIRES): a double-blind, investigator-initiated, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Rheumatology 2021; 3: E489-E497; doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00107-7.

- Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M, et al: Nintedanib for Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. N Engl J Med 2019; 380(26): 2518-2528.

- Betteridge Z, McHugh N: Myositis-specific autoantibodies: an important tool to support diagnosis of myositis. J Intern Med 2016; 280: 8-23; doi: 10.1111/joim.12451.

- Mehta P, Aggarwal R, Porter JC, et al: Management of interstitial lung disease (ILD) in myositis syndromes: A practical guide for clinicians. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2022; 101769; doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2022.101769.

- Aggarwal R, Charles-Schoeman C, Schessl J, et al: Prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III study evaluating efficacy and safety of octagam 10% in patients with dermatomyositis (“ProDERM Study”). Medicine (Baltimore) 2021; 100: e23677; doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023677.

- Bauhammer J, Blank N, Max R, et al: Rituximab in the Treatment of Jo1 Antibody-associated Antisynthetase Syndrome: Anti-Ro52 Positivity as a Marker for Severity and Treatment Response. J Rheumatol 2016; 43: 1566-1574; doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150844.

- Medlin JL, Hansen KE, McCoy SS, et al: Pulmonary manifestations in late versus early systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018; 48: 198-204; doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.01.010.

- Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R, et al: 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome: A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017; 69: 35-45; doi: 10.1002/art.39859.

- Gao H, Zhang XW, He J, et al: Prevalence, risk factors, and prognosis of interstitial lung disease in a large cohort of Chinese primary Sjogren syndrome patients: A case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97: e11003; doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011003.

- Farge D, Ait Abdallah N, Marjanovic Z, et al: Autologous stem cell transplantation in scleroderma. Press Med 2021; 50: 104065; doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2021.104065.

- Kreuter M, Bendstrup E, Russell AM, et al: Palliative care in interstitial lung disease: living well. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5: 968-980; doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30383-1.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(9): 4-9