The sex-specific atypical clinical presentation of acute coronary syndrome and the sex-specific outcomes of cardiovascular disease in women are well known. The aim of this training article is to analyze possible differences between men and women presenting to certified German chest pain centers (CPUs).

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) represent the most common cause of death for women in industrialized countries worldwide as well as in Germany, Austria and Switzerland [1–5] and lead to a shortened life expectancy [6]. Typical manifestation of CVD is acute coronary syndrome (ACS), which is one of the most common reasons for admission to an emergency department. Its subentities are ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and troponin-negative non-elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS). For optimal diagnosis and treatment, specialized chest pain units ( CPU) have been established according to criteria of the German Society of Cardiology (DGK) [7]. Their implementation has improved the quality of care for ACS patients [8]. As of 05/2023, the CPU network consists of more than 360 CPUs in Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

The Acute Thoracic Pain

The classic main symptom of CVD manifestation is acute chest pain, which is the namesake of CPU. The classic pain symptomatology is summarized under the term “typical chest pain”. However, it has been known for many years that CVD presents more frequently with so-called atypical symptoms in women [9], thus the “atypical” symptoms in women represent “typical” ones. To address this discrepancy, recent guidelines increasingly abandon the distinction between typical and atypical and instead focus on the symptom complex: angina pectoris is perceived as a retrosternal chest discomfort that gradually increases in intensity (over several minutes), is usually triggered by stress (physical or emotional) or occurs at rest (as in the case of ACS), and has a characteristic radiation (e.g., left arm, neck, jaw. e.g., left arm, neck, jaw) and associated symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, nausea, lightheadedness). Relief with nitroglycerin is not necessarily diagnostic of myocardial ischemia and should not be used as a diagnostic criterion, especially because other entities show a similar response (eg, esophageal spasm). Concomitant symptoms such as shortness of breath, nausea or vomiting, lightheadedness, confusion, presyncope or syncope, or vague abdominal symptoms are more common in patients with diabetes, women, and the elderly. A detailed assessment of cardiovascular risk factors, a review of systems, medical history, and family and social history should complement the evaluation of presenting symptoms [10].

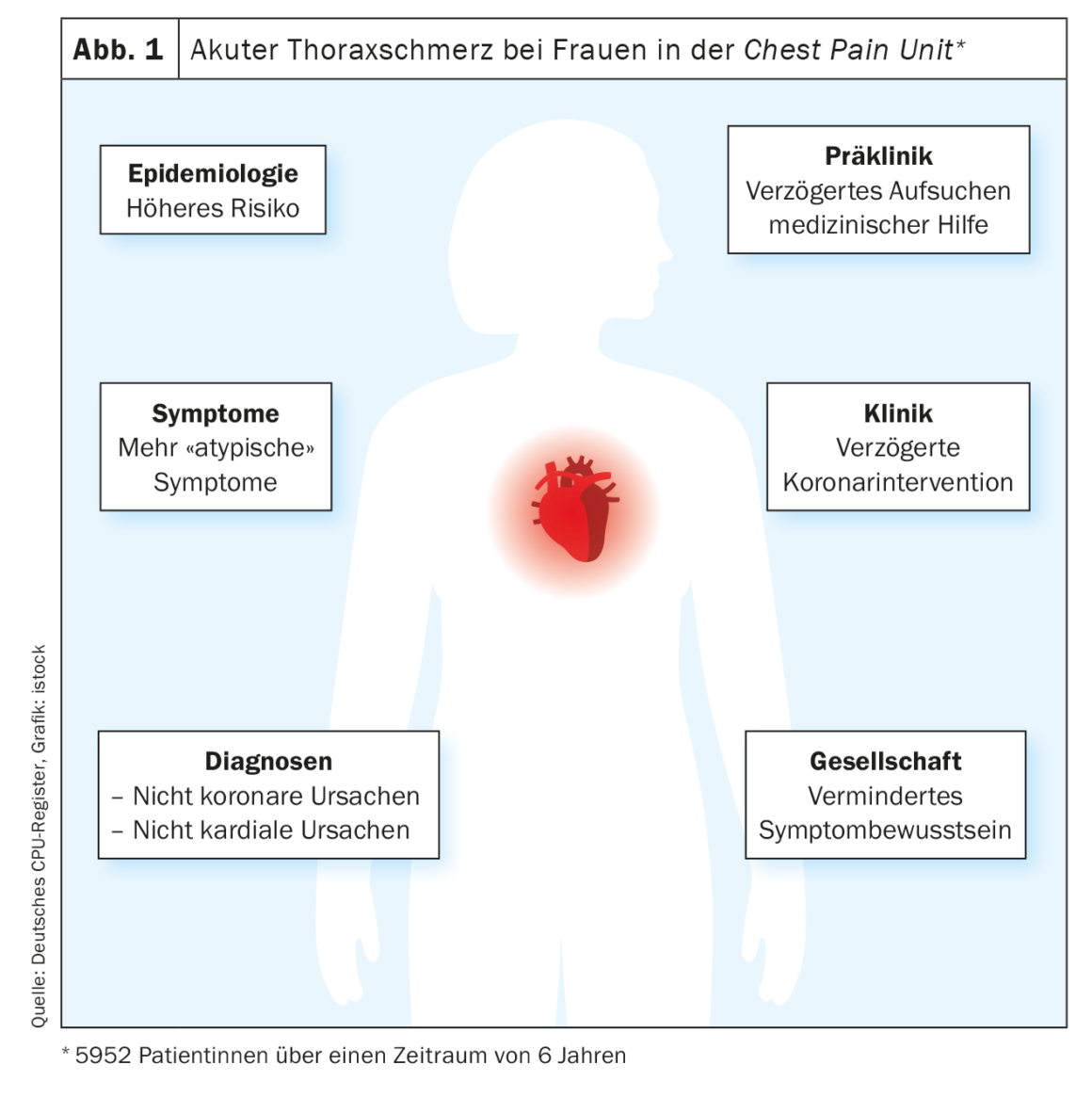

Both European and American guidelines emphasize the need for gender-neutral diagnosis as well as equal treatment [10,11]. Women presenting with acute chest pain are at increased risk of underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis. This is composed of differential symptom awareness, presentation with “atypical” symptoms, decreased or delayed access to the health care system in some cases, and more frequent noncardiac chest pain.

Gender differences arise from both biological (“sex”) and sociocultural (“gender”) sex, although the role of the latter is still underrepresented in research, and many databases, registries, and papers to date differentiate only by biological sex [5,12]. Women are also still underrepresented in large randomized clinical trials [5]. The available data on CPU refer to biological sex due to data collection.

Gender differences in CPU: the proportion of men is higher, women are high-risk patients

The CPU as the initial diagnostic and treatment organ is of special importance. Data from the German CPU Registry provide information about the situation in clinical practice [13]. Across the spectrum of acute chest pain management, before and through initial medical contact to hospital discharge, there are significant gender differences in care.

A total of 13 900 patients presented to chest pain units participating in the CPU registry between 2008 and 2014. 37.8% of all patients were women [f] and 62.2% patients were men [m]. Women enrolled in the CPU were on average almost five years older than men (70.5 [f] vs. 65.6 years [m], p<0.001), more women were ≥75 years old (35.4% [f]vs. 24.3% [m], p<0.001). In contrast to men, women had a lower history of cardiovascular disease (57.8% [f] vs. 62.0% [m], p<0.001), specifically fewer myocardial infarctions, previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), and previous percutaneous coronary intervention ( PCI; all p<0.001). Women had fewer concomitant risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and hyperlipidemia (all p<0.001). After age adjustment, the differences are even more pronounced.

Symptoms and initial clinical presentation: women are more likely to suffer from non-classical symptoms

Classic (“typical”) chest pain symptomatology occurred more frequently in men than in women (72.5% [f] vs. 78.8% [m], p<0.001), while non-classical (“atypical”) symptoms such as dyspnea, palpitations and other symptoms were more common in women (29.8% [f] vs. 27.0% [m], p<0.001; 16.6 [f] vs. 10.0% [m], p<0.001; 19.6% [f] vs. 16.3% [m], p<0.001). GRACE scores, which predict in-hospital mortality, were higher in women than in men in all subgroups. Of all ACS patients, women were more likely to have high-risk GRACE scores>140 (48.9% [f] vs. 44.8% [m], p=0.004), thus actually representing a high-risk collective overall. Men were more likely to show ST-segment elevation or left bundle branch block on ECG (9.5% [f] vs. 12.4% [m], p<0.001).

Although sex differences in troponin levels exist [14], there is no sex-dependent cut-off value in the case of ACS [10,11,15]. In the CPU setting, the proportion of women who had overall elevated troponin levels was 0.7-fold lower than the proportion of men (20.1% [f] vs. 27.2% [m], p<0.001) with significant differences in first and, if performed, second troponin measurements (16.9% [f] vs. 23.9% [m], p<0.001; 22.6% [f] vs. 28.6% [m], p<0.001). In contrast, women were 1.4 times more likely than men to be diagnosed with pathological brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels (48.1% [f] vs. 39.3% [m], p=0.009).

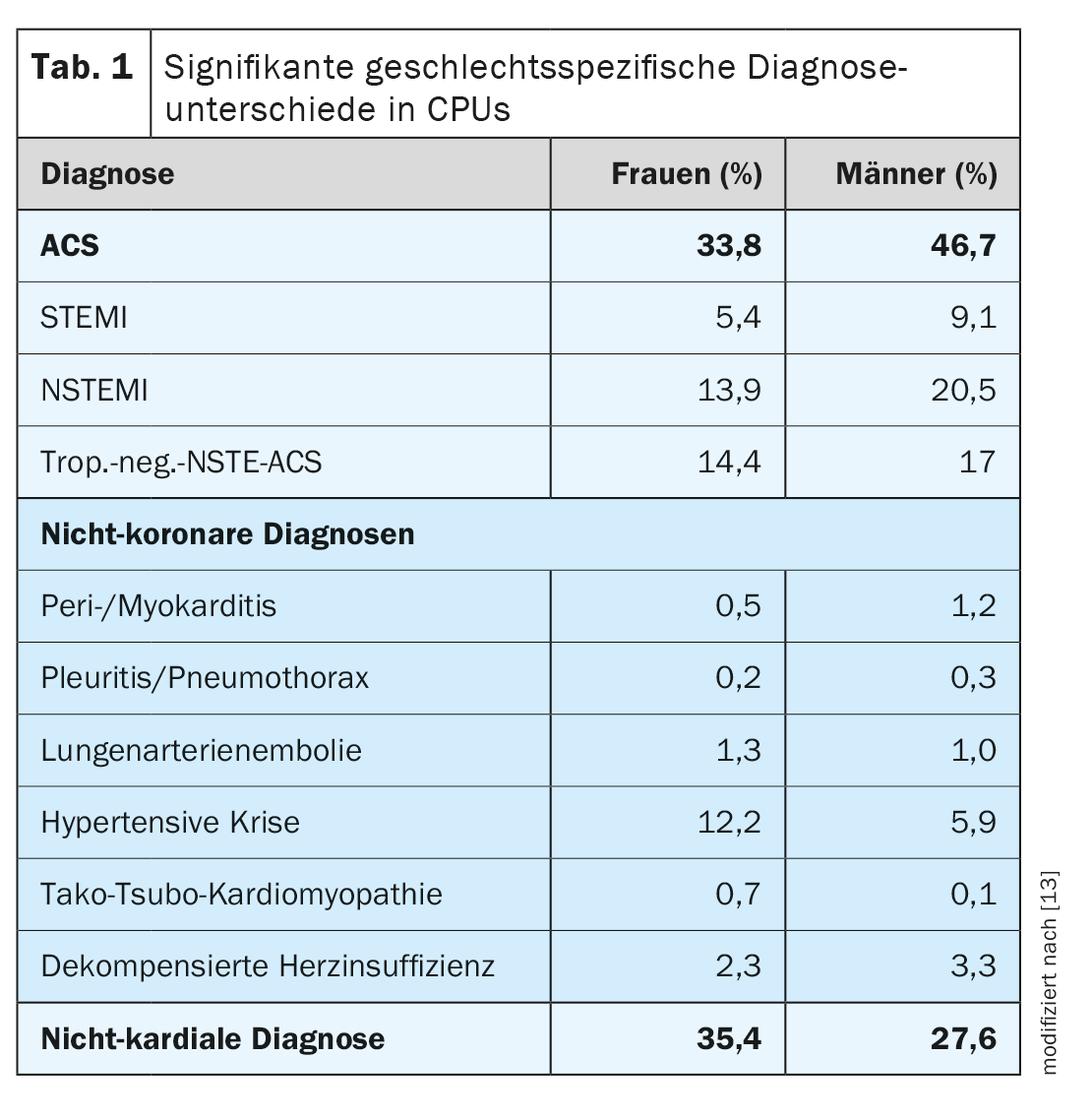

CPU diagnosis: women are more likely to have a non-coronary cause

Analysis of underlying diagnoses revealed that women were less likely to have coronary pathology as the cause in patients presenting with ACS, STEMI, NSTEMI, or troponin-negative NSTE-ACS (33.8% [f] vs. 46.7% [m], 5.4% [f] vs. 9.1% [m], 13.9 [f] vs. 20.5% [m], 14.4% [f] vs. 17.0% [m], all p<0,001). Of note, hypertensive crises (12.2% [f] vs. 5.9% [m], p <0.001), Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathies (0.7% [f] vs. 0.1% [m], p<0.001), and arrhythmias (12.6% [f] vs. 7.5% [m], p<0.001) were documented more frequently in CPU patients. Noncardiac causes were more common in women than in men (35.4% [f] vs. 27.6% [m], p<0.001). Table 1 provides an overview of ACS subentities and noncoronary and noncardiac causes.

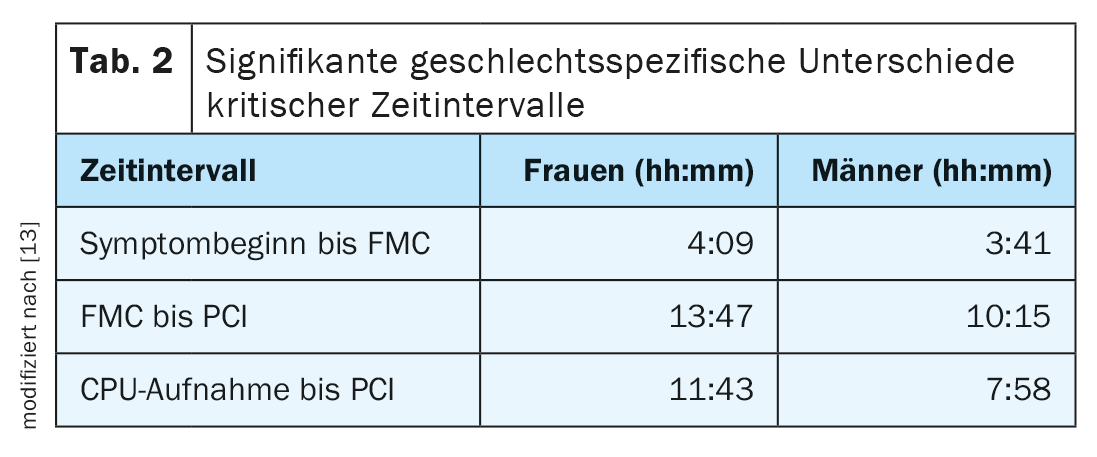

Treatment for women is often delayed

CPU patients waited longer overall to seek medical help after the onset of symptoms (first medical contact; FMC) (4:09 h [f] vs. 3:41 h [m], p=0.018), but tended to be more likely to be admitted to the CPU by the ambulance service (45.0 [f] vs. 42.9% [m], p=0.015; NSTEMI subgroup 45.2% [f] vs. 39.8% [m], p = 0.013), whereas there were no gender differences in terms of general practitioner self-referral. Overall, time intervals from symptom onset to PCI and from FMC to PCI were significantly shorter in patients (13:47 h [f] vs. 10:15 h [m], p=0.022; 11:43 h [f] vs. 7:58 h [m], p=0.009). Table 2 summarizes the gender-specific critical time intervals.

There were gender-specific treatment priorities in the CPU: While treatment in men was more often classified as “immediate emergency” or “in need of urgent therapy” (45.7% [f] vs. 55.4% [m], p<0.001), women were more often treated electively (42.6% [f] vs. 33.6% [m], p<0.001) or conservatively (20.1% [f] vs. 17.4% [m], p=0.002). A higher rate of PCI was found in men (22.6% [f] vs. 33.6% [m], p<0.001). Of the patients who underwent PCI, men received PCI significantly earlier than women (11:43h [f] vs. 7:58h [m], p=0.009).

In STEMI patients, there was a trend toward a longer time interval in women from symptom onset to FMC (2:35 h [f] vs. 2:00 h [m], p=0.080) and from CPU admission to PCI (0:40 h [f] vs. 0:32 h [m], p=0.063). In the STEMI subgroup, a high percentage of patients received interventional therapy with no sex difference (95.4% [f] vs. 96.3% [m], p=0.53). Although not statistically significant, the time interval between symptom onset and PCI proved to be longer in NSTEMI patients in women (31:13 h [f] vs. 29:00 h [m], p=0.20). A higher rate of PCI (55.2% [f] vs. 64.7% [m], p<0.001) and a trend towards more CABG treatments (3.8% [f] vs. 5.7% [m], p=0.066) were observed in male patients with NSTEMI. In the troponin-negative NSTE-ACS subgroup, there is a significantly shorter time interval between FMC and PCI in male patients (32:28 h [f] vs. 25:42 h [m], p=0.025) and a trend toward a shorter time interval between CPU uptake and PCI (26:02 h [f] vs. 22:30 h [m], p=0.055). Furthermore, in the troponin-negative NSTE-ACS group, men were more frequently treated with PCI (27.8% [f] vs. 38.2% [m], p<0.001) or CABG (0.6% [f] vs. 1.7% [m], p=0.038), whereas women were more frequently treated conservatively (65.9% [f] vs. 54.3% [m], p<0.001).

Special group: pregnant patients

The management of pregnant patients with acute chest pain is particularly challenging due to the physiologic changes associated with pregnancy. Pregnancy is associated with a three- to fourfold increased risk of myocardial infarction compared with age-matched nonpregnant women. The etiology of CVD in pregnancy differs from that of the general population; the majority of cardiovascular disease has nonatherosclerotic causes. Pregnancy-related ACS most commonly occurs in the third trimester or after delivery. The clinical picture is the same as in the non-pregnant population. Major differential diagnoses include pulmonary artery embolism, aortic dissection, and preeclampsia. The mother and fetus must be closely monitored, and a delivery strategy must be in place in case of sudden deterioration [16]. Pregnant patients with acute chest pain should be treated – interdisciplinary – in the CPU.

Conclusion & Outlook

Gender differences in cardiac patients are well known. Considering the data from the CPU registry, gender differences were related specifically to symptoms, prehospital time intervals, and underlying cardiac diagnoses. Women were more likely to have nonclassic (“atypical”) symptoms, had a longer prehospital delay, and were more likely to have a nonischemic cause for the pain. All certified CPUs should be aware of these gender differences and should incorporate them into individual diagnostic and therapeutic standards and regularly communicate them to staff in order to better target prodromal forms in women.

In 2008, the DGK’s CPU certification campaign was launched. Prerequisites for certification include a dedicated CPU site, appropriate equipment, diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, cooperation, staff training, and organization. Efficacy and guideline adherence have been demonstrated by a number of studies [17–20]. Nevertheless, despite a distinct organizational and process structure, there is a difference in the treatment of women and men, which cannot be explained by biological differences alone. The next important step should focus on further linking the CPU to the community and increasing symptom awareness – especially among women. In this regard, an early heart attack care ( EHAC) program could be a useful tool as an additional means of educating the public and certifying laypersons to recognize patients with prodromal symptoms of myocardial infarction. Furthermore, in the future, gender-sensitive personalized cardiovascular medicine must take into account equally, especially in the acute setting of CPU, biological as well as sociocultural gender differences.

Take-Home Messages

- Women are delayed in seeking first medical contact at the onset of acute chest pain.

- Women present with non-classical “atypical” complaints.

- The causes of acute chest pain in women are more variable.

- In women, a non-coronary cause is more common.

Literature:

- Mehta LS, et al: Acute Myocardial Infarction in Women: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2016. 133(9): 916-947.

- (Destatis), SB: Most common female causes of death in 2021. 2023 [cited 2023 14.05.2023]; Available from: www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/_inhalt.html#sprg235878.

- Austria S: Cause of Death Statistics. 2023 [cited 2023 14.05.2023]; Available from: www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bevoelkerung/gestorbene/todesursachen.

- Statistics, S.E.B.f.: Specific Causes of Death. 2023 [cited 2023 14.05.2023]; Available from: www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/gesundheitszustand/sterblichkeit-todesursachen/spezifische.html.

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Gebhard C: Gender medicine: effects of sex and gender on cardiovascular disease manifestation and outcomes. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 2023. 20(4): 236-247.

- Jasilionis D, et al: The underwhelming German life expectancy. European Journal of Epidemiology, 2023.

- Giannitsis E, et al: Criteria of the German Society of Cardiology – Cardiovascular Research for “Chest Pain Units”. Der Kardiologe 2020; 14(6): 466-479.

- Breuckmann F, et al: German chest pain unit registry: data review after the first decade of certification. Heart 2021; 46(Suppl 1): 24-32.

- Steingart RM, et al: Sex differences in the management of coronary artery disease. Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Investigators. N Engl J Med 1991; 325(4): 226-230.

- Gulati M, et al: 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021; 144(22): e368-e454.

- Collet JP, et al: 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal 2021; 42(14): 1289-1367.

- Zealand U: Gender-sensitive medical approaches in cardiology. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2023; 148(09): 538-546.

- Settelmeier S., et al.: Gender Differences in Patients Admitted to a Certified German Chest Pain Unit: Results from the German Chest Pain Unit Registry. Cardiology 2020; 145(9): 562-569.

- de Bakker M, et al: Sex Differences in Cardiac Troponin Trajectories Over the Life Course. Circulation 2023;147: 1798-1808.

- Ibanez B, et al: 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal 2018; 39(2): 119-177.

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, et al: 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: The Task Force for the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal 2018; 39(34): 3165-3241.

- Breuckmann F, et al: Survey of clinical practice pattern in Germany’s certified chest pain units: Adherence to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines on non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Heart 2022; 47(6): 543-552.

- Breuckmann F, et al: Unexpected high level of severe events even in low-risk profile chest pain unit patients. Heart 2021.

- Settelmeier S, et al.: Research Article: Management of Pulmonary Embolism: Results from the German Chest Pain Unit Registry. Cardiology 2021: 1-7.

- Breuckmann F, et al: German chest pain unit registry: data review after the first decade of certification. Heart 2020.

CARDIOVASC 2023; 22(2): 6-9