The SGML Congress is now called “Laser & Procedures”. Several presentations focused on non-laser treatments. These include radiotherapy for malignant skin tumors or photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses.

“We think we know almost everything about actinic keratoses (AK). However, this is not true. We are still subject to certain errors, starting with the classification,” explained Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Dirschka, CentroDerm, Wuppertal, by way of introduction. For example, the clinical classification according to Olsen I-III does not correlate with the histological classification according to Roewert-Huber (AK I-III). Consequently, no conclusions about the histology of the lesions can be drawn from their clinical appearance [1]. The principle “the higher the histologic grade of AK, the more frequent a transition to invasive squamous cell carcinoma” also does not apply. AK I stages in particular appear to predominantly progress into such carcinomas [2].

The “AKASI” score

“Counting lesions for severity assessment is difficult to impossible, so new approaches are needed here as well. Similar to the PASI score in psoriasis, we developed the AKASI (‘actinic keratosis area and severity index’) [3]. It divides the head into four regions: scalp, forehead, cheek/ear left-right, and chin/nose.” In each region, the percentage of area affected by AK and the severity of three clinical signs are collected: Distribution, Erythema, and Thickness. There is a strong correlation between the AKASI and the PGA (Physician Global Assessment), i.e., the AKASI increases linearly with the PGA levels of “mild,” “moderate,” “severe,” and “very severe” and is able to discriminate between categories.

The new score could prove useful in clinical trials, but also in everyday practice. Especially since it was recently shown to be associated with the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma [4]: AKASI is significantly higher in patients with squamous cell carcinoma than in those with noninvasive lesions. “Thus, this score actually says something,” the speaker said, summarizing the preliminary study situation.

Treatment of the AK

“Large-area treatment using a combination of different therapies is the only approach that will hold up in the future. The most effective for field treatment is photodynamic therapy (PDT).”

While PDT with the photosensitizing substance methyl 5-amino-4-oxopentanoate (MAL, Metvix®) and high-energy red light produces good results, it also has some drawbacks. These include the time required, i.e. three hours under occlusion between application of the cream and irradiation (total duration of the procedure about 4 hours), but also stronger local reactions and, above all, pain.

“Fortunately, there is an effective alternative in daylight PDT,” the speaker said. All exposed surfaces are first coated with sunscreen (sun protection factor 30 or higher; only chemical, no physical filters, as these partially block visible light). One example is Actinica® lotion. After removal of crusts and scales, a thin layer of Metvix® (cover not necessary) is applied, followed by a continuous two-hour stay in full daylight. Sun is not mandatory (temperature at least 10°C) – however, in case of rain or prospects of rain, daylight PDT is not recommended. There is a maximum of 30 minutes between treatment and exposure to prevent excessive accumulation of protoporphyrin IX, which in turn would cause greater pain when exposed to light (total duration of the procedure is approximately three hours). This is the central difference to red light PDT: Protoporphyrin IX is continuously activated and consecutively inactivated in daylight PDT. Accumulation and thus pain are prevented (visual analog scale of 1-2 versus 6-8 for standard PDT).

“Daylight activates all protoporphyrin IX bands and penetrates deep enough into the skin to treat AKs,” Prof. Dirschka explained. “Studies show no significant difference between the two PDT variants at 12 weeks (COMET 1 for mild AK and COMET 2 for mild to moderate AK). The Metvix®-Daylight PDT works in sunny weather to total cloud cover, just not in rain.” Despite all this, the obvious disadvantage of the daylight variant is that it can be considered only in weather conditions that allow a pleasant two-hour stay outdoors. Usually, the period between the end of April and the end of September is assumed to be the optimal conditions. Otherwise, the stay outdoors turns out to be very unpleasant, especially for older people or at AK sites that are usually overcast.

In the meantime, there are also so-called daylight simulators, where it is no longer necessary to stay outside. However, their validation is currently still pending.

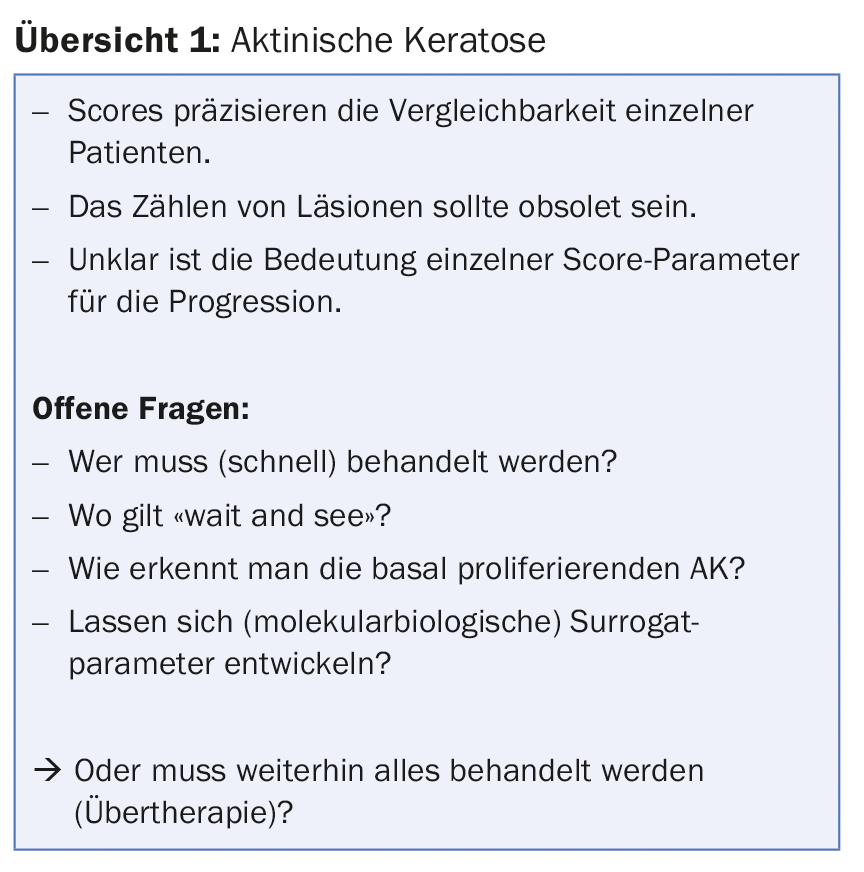

Overview 1 summarizes the new findings at AK.

Dermatological radiotherapy

“The most commonly used energies against malignant skin tumors are in the range of 30-50 KV,” said Markus Notter, MD, Lindenhofspital, Bern. The example of basal cell carcinoma shows that the distance to the visible tumor during surgery can be considerable in certain cases (up to 15 mm safety distance), if one wants to achieve negative resection margins with a probability of more than 95%. “Considering that not only the chances of cure but also the preservation or restoration of the natural appearance, the costs and the expediency are important for the therapy decision, irradiation has its justified place in the treatment of malignant skin tumors,” the speaker explained. Classically, the so-called “facial triangle” falls into their field of indication. These mainly include lesions on the nose, forehead, cheek, but also around the chin/lip area and ears.

Several sessions are necessary for radiation therapy. This is because normal cells divide more slowly and recover better when the radiation is divided into many small individual doses (fractionation). Malignant cells, on the other hand, divide rapidly and are sensitive to each of the fractionated doses of radiation. The recommended fractionation depends on the diameter, tumor type, location, circumstances and age of the patient. “Commonly, ten to twelve sessions of 5 Gy three times per week give the best (and most cosmetically pleasing) results – but not in larger lesions. There, for example, 12-15 sessions of 4 Gy three times a week can be used. For smaller lesions, three to five sessions of 8 Gy once a week are feasible,” the speaker noted. Either way, you have to expect about five weeks of therapy. Elderly and senile patients with transportation difficulties require an individualized treatment plan.

“Control rates of basal cell carcinoma by radiotherapy are around 95% or more according to the literature. Recurrences fare somewhat worse. This is with excellent cosmetic results in the majority of cases,” said Dr. Notter. “Of course, adequate therapy selection requires discussion in the tumor board, where all treatment options for the individual case can be discussed, as well as careful patient education about the side effects of radiotherapy.” Today, these still mainly include acute problems such as tumor demarcation and necrosis, bleeding, wound formation and crust formation, but also chronic side effects such as depigmentation, atrophy and telangiectasia.

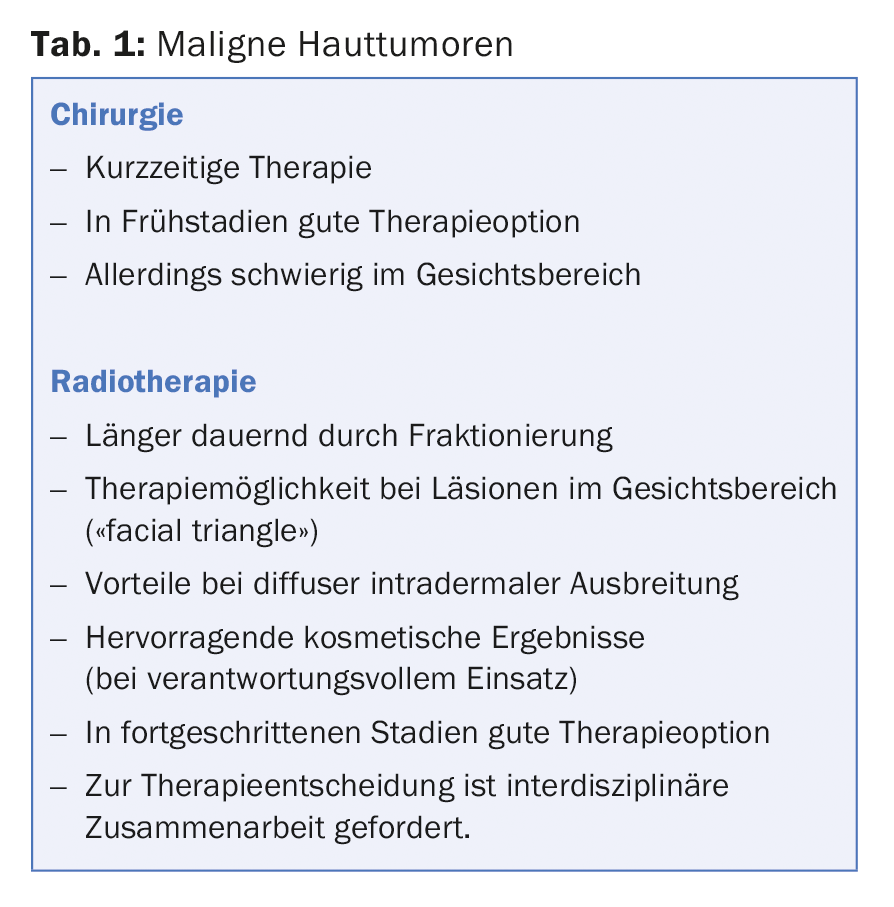

An overview of surgery and radiotherapy for malignant skin tumors is shown in Table 1.

“In benign skin diseases, radiotherapy has analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects, among others, even at the lowest doses. However, it leads an even bigger ‘Cinderella existence’ here than in malignant lesions,” explained Dr. Notter. Somatic damage is not expected at such low doses. To prevent genetic damage, however, gonadal protection is needed. The most current issue is likely to be tumor induction (solid tumors, leukemias). “However, you have to put the risk somewhat in perspective: It can be compared with 2.5 mSv of ionizing radiation, for example, with the risk for an accident while driving 1000 km by car, or with the risk from air pollution during a 50-day stay in New York, or for a crash while flying 62,500 km by plane. Radiation therapy can thus also be an option for some non-malignant skin diseases with sometimes serious consequences or even life-threatening courses (with the appropriate know-how).”

Source: SGML 18 Laser & Procedures, January 18, 2018, Zurich

Literature:

- Schmitz L, et al: Actinic keratosis: correlation between clinical and histological classification systems. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016 Aug; 30(8): 1303-1307.

- Fernández-Figueras MT, et al: Actinic keratosis with atypical basal cells (AK I) is the most common lesion associated with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015 May; 29(5): 991-997.

- Dirschka T, et al: A proposed scoring system for assessing the severity of actinic keratosis on the head: actinic keratosis area and severity index. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017 Aug; 31(8): 1295-1302.

- Schmitz L, et al: Actinic keratosis area and severity index (AKASI) is associated with the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017 Nov 8. DOI: 10.1111/jdv.14682. [Epub ahead of print].

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(1): 33-35