In an interview with DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS, Dr. med. Daniel Fuchs, Skin and Laser Center on the Limmat, Zurich, provided information on the topic of “Acne scars and new therapeutic approaches”. He discussed the different manifestations of scars and possible factors that influence scarring. Regarding therapy, he emphasized the advantages of medical micro-needling in combination with radiofrequency and fillers.

Dr. Fuchs, what types of scars can result from acne and which type is most common?

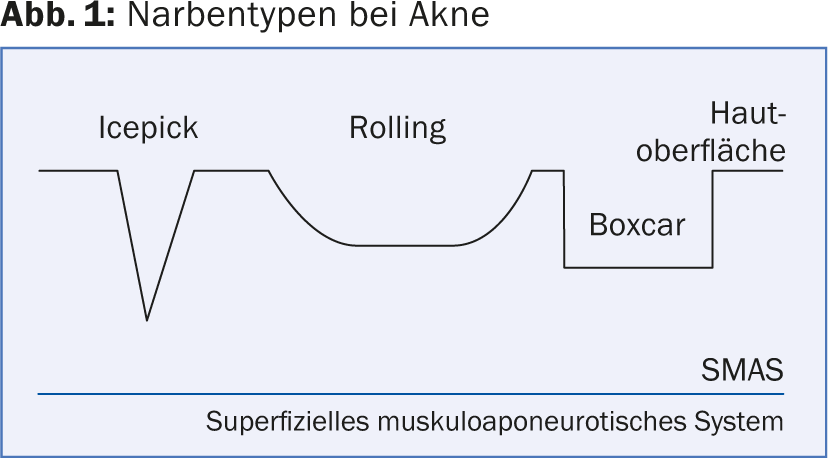

Dr. Fuchs: Classic scar types that can result from acne are the so-called “boxing scars” (dimple-shaped sunken and square), “rolling scars” (wave-like) and the “ice-pick scars” (pointed/conical) ( Fig. 1). Keloids are less common. These tend to be found on the body (neck and shoulder region), but can also occur on the face, especially in the context of acne conglobata.

Most often, acne scars occur when acne is not treated or is already “burned out”.

What pathological processes lead to acne scarring?

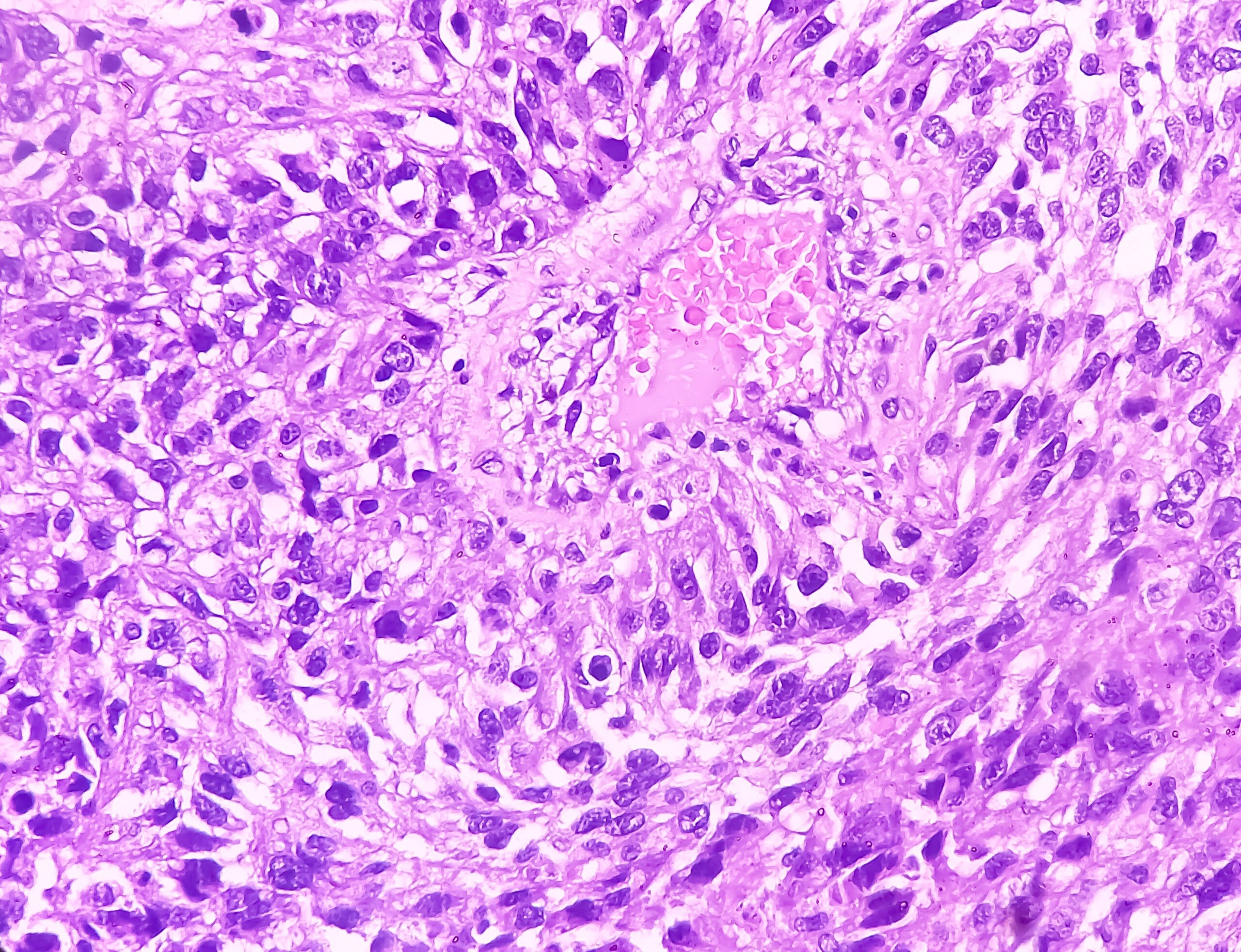

What is clear is that scarring involves impaired wound healing, which is accompanied by the formation of replacement tissue. In principle, the inflammatory reaction is sufficiently deep in all forms of acne that scars can develop (similar to varicella-zoster, for example). As a sebaceous gland disease, acne always affects deep layers of the skin, even the so-called blackhead acne (comedonica) can result in scarring – here it is predominantly “ice-pick scars” and somewhat more rarely “boxing scars” that develop. In acne conglobata, all three forms are common, but “rolling scars” are especially common.

Does the individual predisposition play a role or are rather severity and duration of acne favoring factors for scarring?

Acne itself, of course, has a hereditary background, so the risk of disease is genetic. In this respect, genes indirectly influence the likelihood of scarring, as scars are a subsequent reaction of acne. However, in my opinion, the severity and duration or the course of acne play a subordinate role, because as described above, scars can occur with all types of acne. We more often observe more severe forms of acne in men, such as acne conglobata, and also tend to see more scarring. In principle, however, you encounter everything and it is like everywhere in medicine: the earlier you diagnose and treat the disease – in this case acne – the greater the chances for a scar-free acne healing.

Do you treat scars even if inflammatory acne efflorescences are still present? Can the scar therapy take place at the same time as the acne therapy (e.g. with isotretinoin)?

A distinction must be made here: It is correct that acne scars are not treated in patients who still have efflorescences. In the case of acute florid acne in the context of an inflammatory reaction, conventional therapy methods such as laser or radiofrequency/medical micro-needling can therefore not be carried out. Rather, one must wait until the inflammatory form of acne (be it conglobata or papulopustulosa) has subsided.

Isotretinoin, as the most potent systemic acne therapeutic agent, can not only prevent acne scars but also improve them to some extent. Unclear according to current studies is the exact percentage degree of this improvement by isotretinoin. What is known, however, is that it has some collagen-stimulating effect.

In my experience, therefore, certain types of scar treatment are fine concurrently with isotretinoin therapy as long as the acne is no longer florid, i.e., there is no longer an inflammatory form. Some benefit of concurrent treatment can even be seen. Neither medical-micro-needling nor filler or radiofrequency are contraindicated under isotretinoin treatment. I often use them in combination with very good results.

Does the skin condition improve in some patients in the long-term course without therapeutic help?

No, rather not. A scar remains a scar. It consists of replacement tissue rather than normal skin. You have to communicate that to the patient. The expectations of those affected regarding the success of the therapy are also often too high. Today, we have very good treatment options at our disposal. However, scar therapy is always only improvement measures, according to the principle: “improve is not remove”.

After all, an acne scar rarely comes alone: how do you counteract this circumstance therapeutically?

Acne scars are found in descending frequency temporally, on the cheeks and on the chin. With all treatment methods, both areal and local acne scar therapy is possible. Depending on the patient, one or the other strategy is applied accordingly.

The variety of therapies is relatively large, including mechanical measures, laser, application of fillers, peelings, etc. Which do you personally use depending on the indication?

It must be emphasized in advance that patient motivation is a very central pillar of both acne and scar therapy. The suffering of those affected is extremely high and should not be underestimated. Scars (just like efflorescences) are highly visible, restrictive and psychologically stressful. You should always keep that in mind. It is therefore necessary to realistically inform the patient about the options and motivate him or her for the respective treatment method.

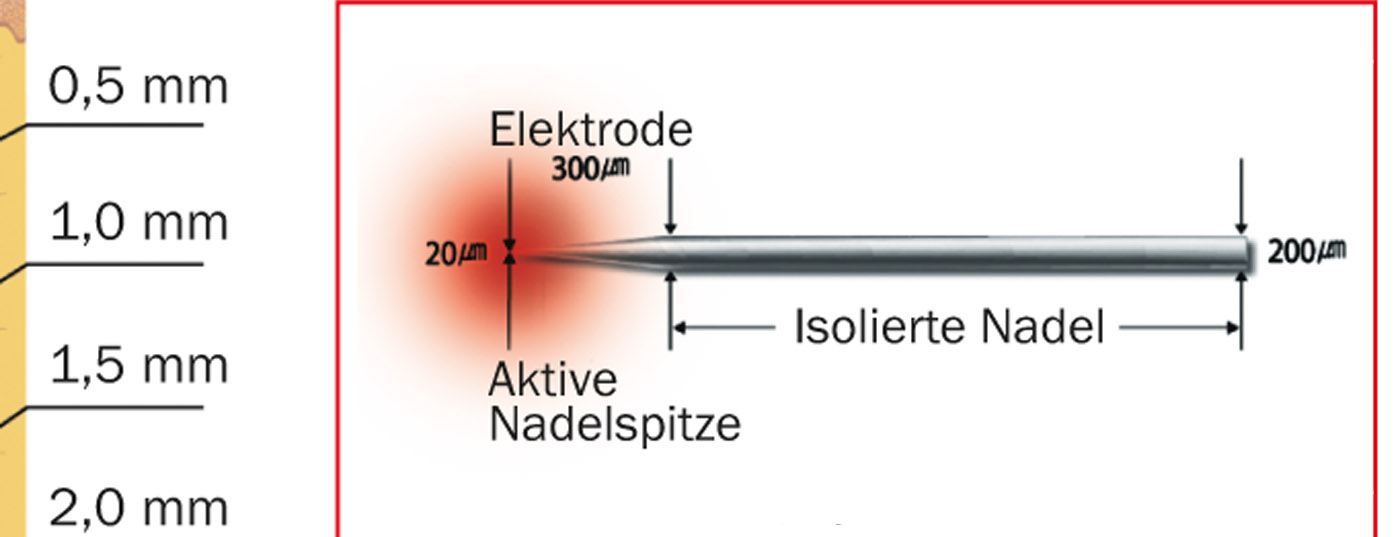

For acne scars, in my experience, combined scar therapy is the most successful. First-line treatment in my clinic for scars that do not exceed 1-1.5 cm is medical micro-needling plus radiofrequency (Fig. 2). Optionally, ablative fractionated radiofrequency can be added, which then works like a laser (but without light). Particularly in the case of “rolling scars” and “boxing scars” over 1.5 cm, we use fillers as a second-line therapy in addition to the above – either hyaluronic acid or calcium gel (Radiesse®). These options are applicable under isotretinoin. The interim analysis (usually after six to nine sessions) then shows us whether we can extract even greater benefit with another additional procedure.

If you opt for a chemical peel, you have to use trichloroacetic acid (TCA), which is a medium-deep peel, to get a reasonable effect. Fruit acids are too weak. Here, however, isotretinoin is contraindicated, one must wait until such treatment is completed.

Filler substances are also very effective. I use mainly calcium hydroxylapatite, as already mentioned. Own fat is a variant for very large scars, but very costly and complicated. I personally do not use it. Fillers are basically not permanent, but when combined with radiofrequency and medical micro-needling, permanent results can be achieved. This combination helps us optimally stimulate collagen. The filler stimulates not only through the mechanical process of pricking with the needle itself, but also chemically. Calcium hydroxylapatite is a very good collagen stimulator.

In principle, most of the therapeutic options discussed are suitable only for atrophic scars. Only theCO2 laser(whether fractionated or unfractionated) is also used for hypertrophic scars.

What advantages do newer approaches like medical micro-needling plus radiofrequency offer over earlier ones?

In my experience, the results of medical micro-needling plus radiofrequency are simply better than those of the other variants such as laser or chemical peels. We achieve 30-40% improvement for atrophic scars, while withCO2 laser you can achieve about 20-30% improvement. It has been my personal experience that many patients are not satisfied with the treatment results of the Fraxel CO2 laser, and I am fully convinced that the newer approach is the significantly better option – even though direct comparative studies (e.g., facial half comparisons) do not currently exist. For hypertrophic scars, theCO2 laser is obviously superior, but acne scars are predominantly atrophic.

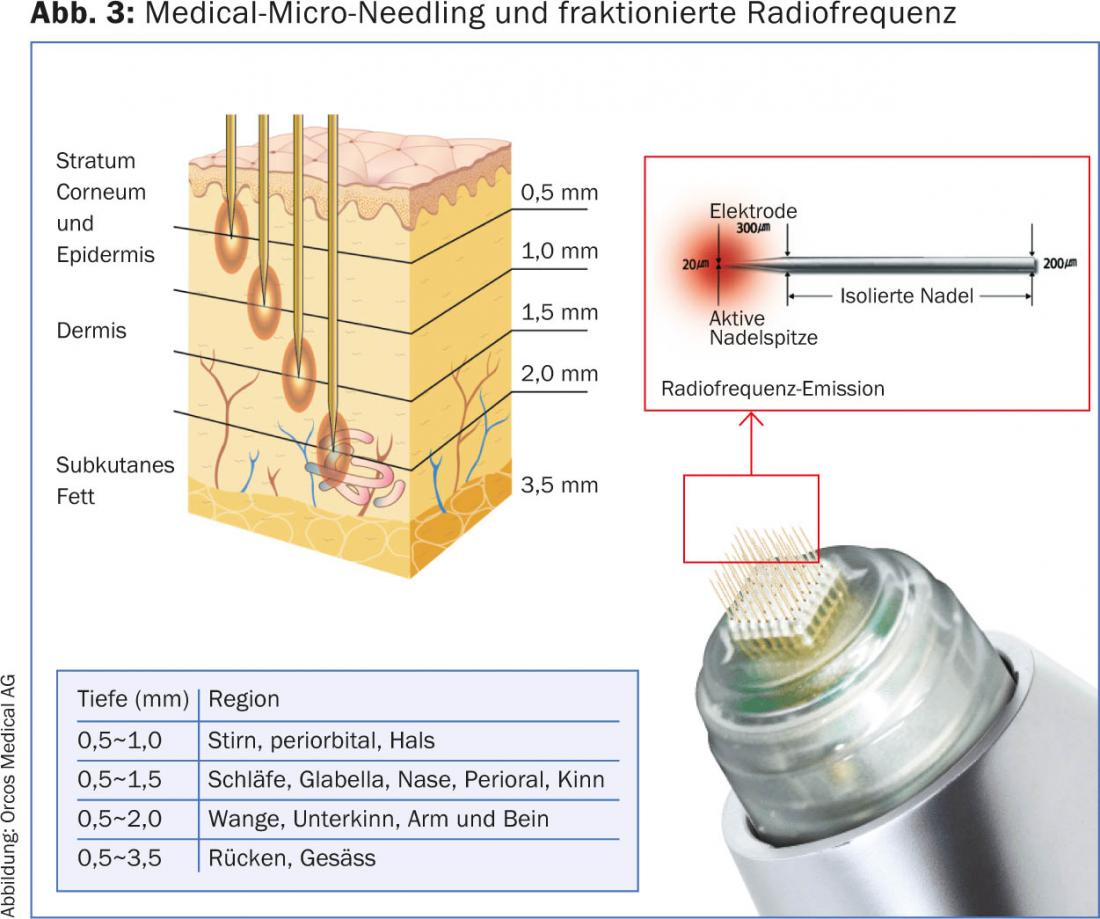

In comparison to theCO2 laser, micro-needling can also be used to treat all skin types, which is an important advantage. The depth of therapy can also be precisely determined and varied by means of the length of the needles in medical micro-needling, which is another advantage over the laser.

How exactly does this therapeutic approach work?

Medical micro-needling has been around since about 1995, and radiofrequency plus micro-needling since about 2000.

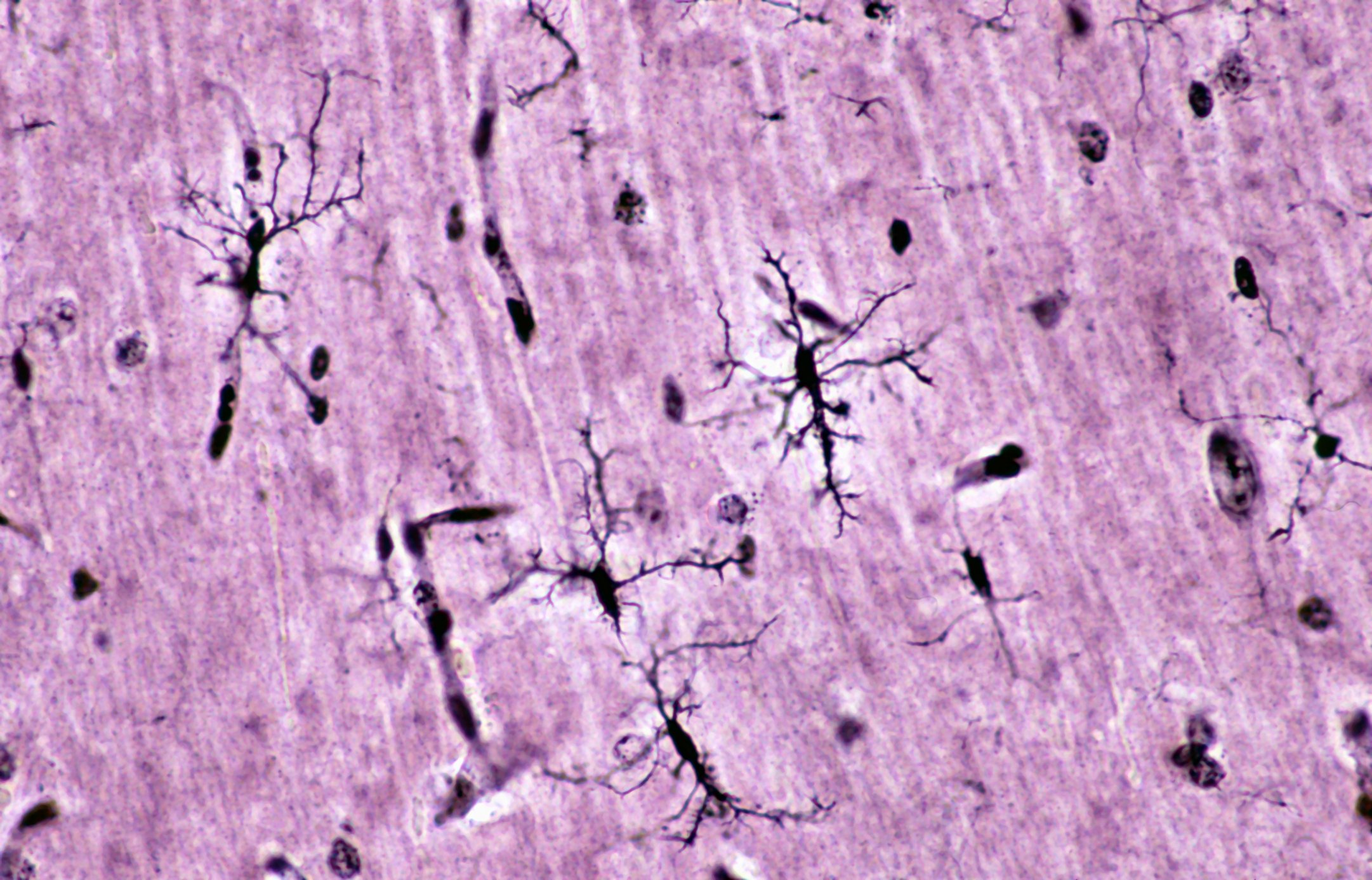

With smallest needles (variable in length up to 3 mm), e.g. attached to a special roller, one causes numerous micro injuries. Collagen formation is then stimulated during wound healing. The heat of the radiofrequency further enhances the effect (Fig. 3).

Medical micro-needling and radiofrequency are not completely painless: without local anesthesia, the pain is three to four on a scale of 10, depending on the patient; with local anesthesia, it drops to about two. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is the most likely complication. It is recommended to avoid sunlight for about two weeks before and two weeks after treatment due to inflammatory reaction/wound healing (we do not offer such therapies in July and August).

How many treatments are needed and is there a downtime?

The first results can be seen after the first application. The whole 60-80% of improvement is seen after about six treatments (with four weeks minimum interval each, i.e. after 24-36 weeks). The number of sessions depends not only on the severity of the scars, but also on the age of the patient: The older the patient, the more effort and the more sessions are necessary to achieve a correspondingly satisfactory result. Most of our patients with acne scars are between the ages of 25 and 50.

The downtime of radiofrequency is significantly shorter than with laser, for example. It is from three to a maximum of five days. Ideally, treatment takes place on Thursday so that the patient can return to work on Monday.

Where do you see the future of acne scar treatment?

I see the future in combination treatments, possibly with the additional use of Platet Rich Plasma to provide even greater collagen stimulation in the depths of the acne scars. Platet Rich Plasma contains a lot of Growthfactors, but is still rather in an experimental stage. Initial trials are underway, but we will have to wait and see how this potentially new form of therapy develops in the future.

Interview: Andreas Grossmann

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(1): 13-16