In the age of sporting superlatives, doping is always topical. Implementation often requires in-depth biological, and in some cases medical, expertise. The question arises to what extent physicians are involved in the process of doping and within what legal framework they operate in this regard.

Probably in every human activity some stain can be found, in sport without much discussion it is doping, and medicine is not uninvolved in it. But with pleasure “she” does not talk about it! To some degree, it is surprising that trade publications rarely drop a line on the subject. On closer analysis, however, this can perhaps be understood: The trade press advocates rational pharmacotherapy, something that is a distant priority in doping. There are probably also other reasons for this dismissive attitude: except for a few cases, although strongly presented in the media (Ben Johnson’s doctor in Seoul in 1988, or the Spanish gynecologist Fuentes), doctors are (surprisingly) extremely rarely involved in doping scandals, at least in relation to the number of positive doping cases worldwide. One might think that medicine is officially not involved. This is despite the fact that doping often involves specialists in the background of athletes who, to be effective, must have biological knowledge. The latter explains a frequently expressed public suspicion of the medical profession. For reasons that are easy to imagine, no one knows exactly how often doctors play an active role in doping crimes. It goes without saying that medical professionals are not the only dispensing source of medications. A quick surf on the Internet shows how easy it is to obtain doping products. However, it would be naïve to believe that the medical profession has no role to play. To our knowledge, no Swiss physician has been convicted of doping practices to date. However, the analysis of the cases handled by the Disciplinary Chamber for Doping Cases of Swiss Olympic shows that sometimes a not insignificant responsibility lies with members of the medical profession. A reason, then, to ask what a doctor – embroiled in a doping issue – would risk.

So, for these and other reasons, it does not seem unnecessary for the physician to be informed about some basics related to doping. Not least to protect himself, but also perhaps to play an important role in the fight against doping through his knowledge of the subject.

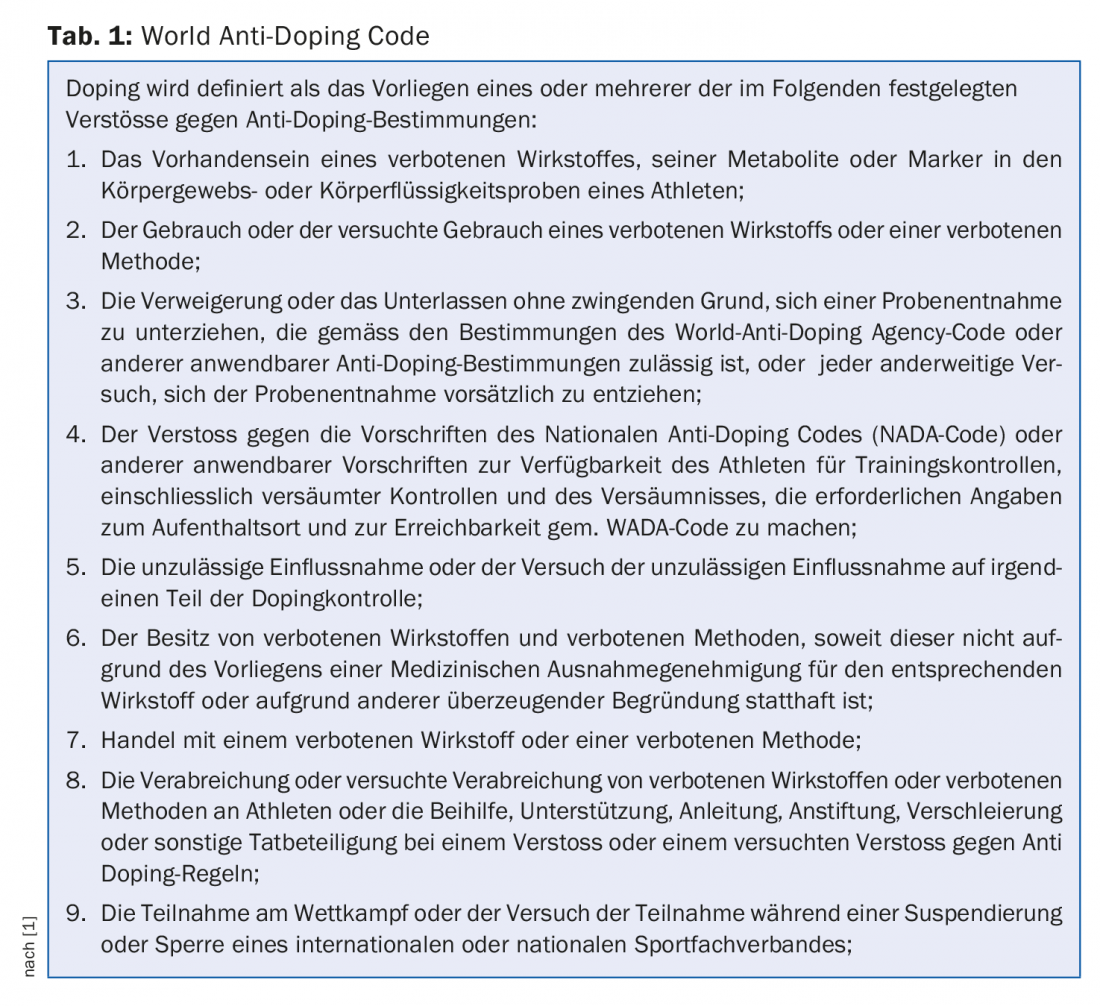

Definition doping

Even though there is a lot of talk about it, it may be useful to remember what exactly doping is. Efforts to find a universal definition of doping have been unsuccessful over the years. Today, therefore, one is content with legal explanations (Tab 1).

An active substance or method is prohibited in the above sense if it is accordingly listed as prohibited in the “List of Prohibited Substances and Methods” of the World-Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) at the time of the violation. This list is not part of the Articles of Association.

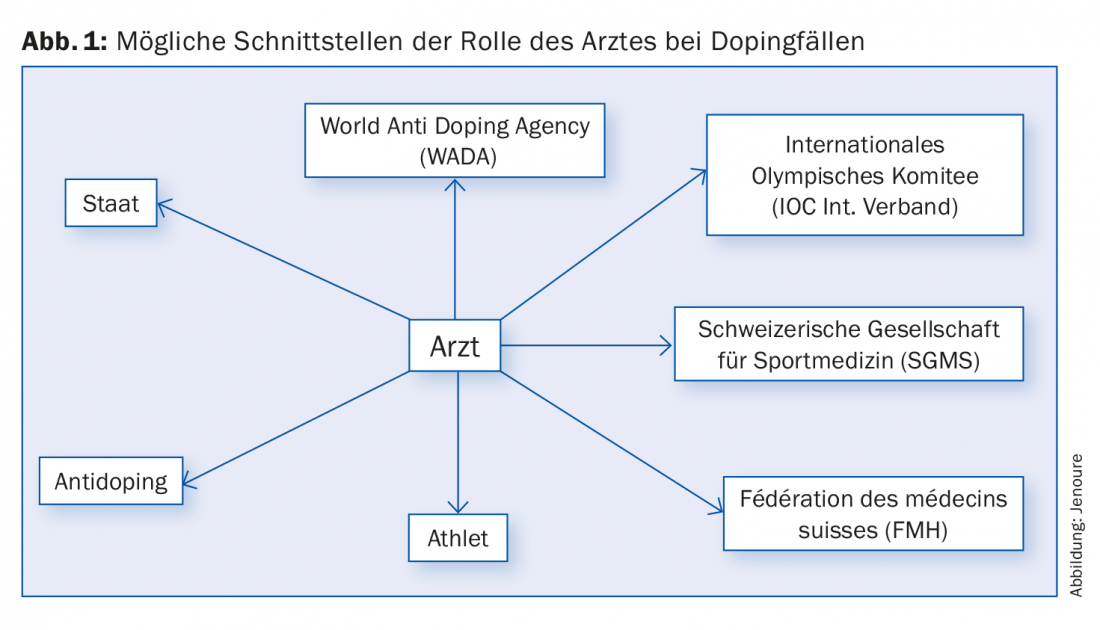

As can be seen, theoretically, the physician can be involved at various points.

The doping list

For physicians, the doping list plays a central role. It determines which pharmaceutical preparations and medical measures are to be used in athletes with restraint, even great caution (see paragraph on exceptional authorization for therapeutic purposes).

This list has been compiled and adjusted annually by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) since 2004. However, in addition to medications whose use in everyday medicine is not exactly considered common, there are also quite conventional preparations that are regularly used in the practice of general practitioners and specialists. This list can easily be found at www.antidoping.ch.

Exemption permits for therapeutic purposes

If an athlete absolutely needs a drug on the list, then there is an exception authorization rule (ATZ) that allows its use. An ATZ is only approved in accordance with certain criteria. An ATZ may be submitted after the fact for emergency treatment. With the help of his doctor, the athlete must provide a form with all the necessary information to justify the use of a prohibited drug. This form is examined by an expert group for national athletes in the country (in Switzerland a commission of Antidoping Switzerland). Only after receiving a positive confirmation, the athlete may start the planned therapy. An emergency clause is provided. This approach clearly represents the most common point of contact with the doping issue for the practicing physician.

The legal framework

Today, there is a complex international and national set of rules in the doping scene, in which the physician must also operate in order to be able to correctly perform his task as an advisor and caregiver of athletic patients (Fig. 1).

Internationally, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) Anti-Doping Code applies uniformly. This document serves as the basis for all other sporting but also non-sporting rules. It provides not only athletes as doping offenders, but all potential “accomplices”. Doctors are mentioned by name. In the latest edition of the Code (2015), athletes are even encouraged to declare accomplices or other participants in order to benefit from the privilege of penalty reduction, an incentive not to be underestimated for the athlete who has become conspicuous. Furthermore, it is important to know that WADA maintains a publicly accessible list of persons banned for violating the Anti-Doping Act!

Swiss law

In Switzerland, public law is governed by the Sports Promotion Act (SpoFöG) and the Medical Professions Act (MedBG), while private law is governed by the Swiss Olympic Doping Statute 2015 and the FMH Statutes, in particular the Code of Professional Conduct. In the second section of the fifth chapter of this order, doping is discussed in detail. Punitive measures are mentioned, such as imprisonment or fine, both cumulative. In the associated section on the promotion of sport and exercise, there is even a list of illicit substances and methods, surprisingly not quite identical to the better known and more frequently used list of the sports world – Switzerland included! Although the MedBG does not mention doping, it can be assumed that the law could be applied in the event of a breach of good medical practice, which is governed by this law.

Every practicing physician must be a member of the Fédération des médecins suisses (FMH) in one form or another, and is therefore also subject to its rules, including the outdated code of ethics that deals with doping. However, for this to come into effect in a doping case, there must be a denunciation (e.g. other FMH member, aggrieved athlete). Violations of the Code of Professional Conduct revealed in this manner can result in severe penalties such as large fines, suspensions, and even bans from practice.

In practice, the most commonly used “law” is Swiss Olympic’s doping statute. Its Disciplinary Chamber for Doping Cases decides on the punitive measures in case of violation of the doping regulations. However, it is only entitled to condemn members of federations that belong to Swiss Olympic. Since physicians usually perform their association activities voluntarily (without a contract), it is difficult to penalize them. However, in case of proven misconduct, suspension from the national and possibly international federation as well as the national and international Olympic Committee must be expected. Finally, the Swiss Society of Sports Medicine (SGSM), to which most sports physicians belong, can also expel guilty members, which in the given case is linked to the loss of the certificate of competence in sports medicine.

Conclusion

It must be clear from this information that a physician who makes himself available to a sports federation or club uses his criminal, civil, professional and sporting responsibilities, with the corresponding various procedures and penalties.

The fight against doping has clearly intensified, at least officially, whether on a sporting or political level. In order to achieve this goal, a complex set of rules has been “woven”, which we have briefly tried to present from the point of view of the physician – potential “victim”, mainly in order to inform him, for the purpose of self-protection. Because this specific knowledge is hardly known and little taught. Good information is by far the best prevention against unpleasant, even intrusive difficulties, especially if the transgression of the law has occurred unintentionally.

Source: Jenoure P: Risques encourrus en Suisse par un médecin impliqué dans une affaire de dopage. Swiss Sports & Exercise Medicine 2016; 64(4): 37-40.

Literature:

- World Anti Doping Agency: World Anti-Doping Code. 2015; www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/the-code

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(7): 4-5