At the Annual Swiss Psoriasis Day in Basel, the benefits of international and national psoriasis registries were discussed. Furthermore, the possibility of therapy optimization in severe and moderate plaque psoriasis was discussed. If there are no safety concerns, switching from conventional and biologic medications to subsequent therapies does not necessarily involve a wash-out period. The wide range of comorbidities, in particular cardiovascular and arthritic conditions, was also the subject of the lecture series.

Prof. Dr. med. Matthias Augustin, Hamburg, spoke about the benefits of European psoriasis registries. A patient registry is an organized system,

- which works according to the methods of an observational study.

- that collects uniform data (clinical and other).

- which evaluates specified results.

- that refers to a population defined by a disease, specific health condition, or therapy.

- that serves a predetermined scientific, clinical, or policy purpose.

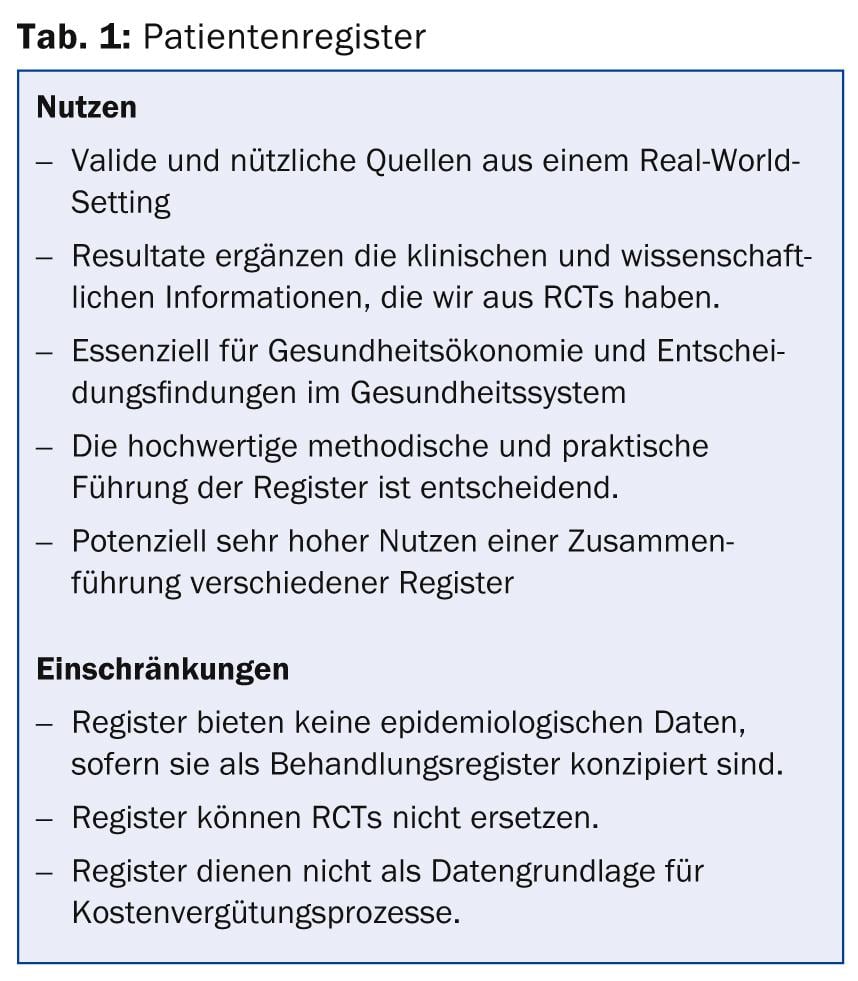

“With the help of a registry, therefore, it should be possible to collect and compare the clinical effectiveness or financial cost of one or more different therapies. The long-term safety or harmfulness of specific drugs or treatments is thus assessed in order to improve the quality of care. Furthermore, a registry can be evaluated for incidence and prevalence data as well as disease trends over time,” Prof. Augustin summarized (Table 1).

Registries have the advantage of enrolling patients who would not have made it into clinical trials (RCTs). On the one hand, this of course limits the informative value of the registries in terms of research, but it is more in line with real clinical practice [1]. For example, it could be shown that the risk of developing severe side effects of biologic and non-biologic psoriasis system therapy was higher for patients who were in registries but not eligible for RCTs [2]. Registries thus provide insight into drug safety and efficacy in a real-world setting.

“Thus, the conditions in RCTs do not always correspond to everyday clinical practice. However, recommendations based on expert consensus are not based on empirical data, and guidelines usually tend to be oriented toward the uncomplicated patient. It is precisely these gaps that registries can fill, for example, by using fixed endpoints such as the PASI score to analyze real-world data and test therapies,” Prof. Augustin explained. One such international psoriasis registry is the so-called PSOLAR, which includes a total of 12 035 patients, 1038 of whom are from Europe.

“Increasingly, these registries are providing data that are summarized in publications. One example is the Spanish Biobadaderm [2]. And yet, it should be noted: Efforts to bring registries together, for example in a European network (PsoNet), must not forget the differences between countries and health systems. They represent a challenge for the interpretation of the data [3]. The number of patients treated per dermatologist, the prior therapy, the use of biologics – there are major differences internationally,” explained Prof. Augustin.

Therapy optimizations

How can the therapy of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis be optimized? This question was discussed by Prof. Dr. med. Ulrich Mrowietz, Kiel: “Psoriasis is an inflammatory systemic disease, which must be approached taking into account comorbidity and trigger factors. Programs against obesity and smoking are useful here. The goal of psoriasis management must be to improve skin symptoms, but also concomitant diseases. Not to forget comorbidity in the psychological area: psoriasis patients often suffer from it.”

The guidelines provide for systemic therapy in severe forms, either conventionally “firstline” with ciclosporin, fumaric acid ester, methotrexate, phototherapy and retinoids, or with biologics “secondline” adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and ustekinumab.

Therapy Targets Algorithm: If the ∆PASI is <50 compared to baseline, therapy must be adjusted. If it is ≥75, it can be retained and continued. In the intermediate range (∆PASI ≥50 <75), the DLQI is crucial. If this is >5, therapy must be adjusted; if it is ≤5, it can be continued [4]. “Options for adjusting therapy include increasing or decreasing dosing intervals, combinations with topical or systemic medications, or ultimately changing therapy or medication. Switching scenarios vary (see box) and little literature evidence exists [5].

In any case, drugs can be changed in case of insufficient efficacy (primary/secondary treatment failure), intolerance or for safety reasons (occurrence of side effects),” said Prof. Mrowietz. “However, there is no established definition of an inadequate clinical response. In published clinical trials with TNF antagonists, the primary nonresponse has been defined as failure to achieve a PASI 50.”

Conversion from conventional drugs

Acitretin: No treatment success with acitretin after 24 weeks despite dose escalation. Switching to anti-TNF or ustekinumab can be done without a washout period. Acitretin can also be used overlapping or concurrently with these biologics.

Ciclosporin: No treatment success with ciclosporin after 16 weeks despite dose escalation. Switching to anti-TNF or ustekinumab can (arguably) be done without a washout period. According to current knowledge, a short overlap with ciclosporin seems to reduce the risk of treatment relapse.

Methotrexate: no treatment success with methotrexate after 24 weeks despite dose escalation. Switching to anti-TNF or ustekinumab can be done without a washout period. Methotrexate can also be used overlapping or concurrently with these biologics.

Switching from biologics

Efficacy: In principle, experience shows that the first biologic remains effective the longest. However, if a switch to another biologic is required because the first one is not effective enough, the switch is made at the normally scheduled time of intake without a washout period. This first with the induction dose, then with the maintenance dose.

If the initial drug is adalimumab, the time until the next normally scheduled dose or switch is usually two weeks. If it is etanercept, it is one week. With infliximab, switching can be considered as early as two to four weeks after the last dose of infliximab, especially in cases of treatment failure. Even with ustekinumab, where an interval of eight to twelve weeks would actually result, a switch is possible as early as two to four weeks after the last dose (again, in the case of treatment failure).

Safety: If a switch to another biologic is decided because of safety considerations, a therapy-free interval may be necessary until the respective safety parameter has normalized or stabilized.

Re-treatment with the same biologic: “In principle, it can be said that better efficacy results can be achieved with continuous biologic therapy over a longer period of time than with interrupted therapy. After a break in therapy, a loss of efficacy can occur when treatment is repeated with the same biologic,” says Prof. Mrowietz.

Comorbidity

“Psoriasis rarely comes alone,” Prof. Wolf-Henning Boehncke, MD, of Geneva University Hospital, introduced his presentation. “From the multitude of comorbidities, I would like to single out two groups, namely the cardiovascular/metabolic and the arthritic conditions. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is itself an extremely complex disease and has multiple disease manifestations. If PsA is to be co-treated, it is important to be aware that it is not simply a little sister to rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This form is more widespread than originally thought and should be diagnosed early if there are dermatologic changes.”

Screening for PsA, for example, can be supplemented with simple questionnaires where the patient ticks off which and how many joints cause him discomfort. Peripheral PsA is initially treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; DMARDs may be used for persistent arthritis/synovitis, and TNF-alpha inhibitors for enthesitis or dactylitis. These TNF therapies with adalimumab [6], etanercept [7], and infliximab [8] have high response rates in PsA. Results of a phase III study of ustekinumab were also presented at EULAR 2012, which are also promising: Like TNF therapies, the drug improved skin and joint symptoms [9].

“For a long time, cardiovascular conditions in psoriasis patients were thought to arise solely from the common risk factors of the two disease complexes: e.g., obesity and metabolic syndrome [10]. Today, there are concepts that view psoriasis along with obesity as the origin of a disease pathway that can lead to myocardial infarction via systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, and atherosclerosis. This would give us an idea of how psoriasis contributes to cardiovascular comorbidities [11]. Further evidence needs to be collected here,” said Prof. Boehncke. This would also have consequences for the choice of therapy: Do insulin agonists possibly have an anti-psoriatic effect [12]?

Knowledge of comorbidities is also important because in certain cases systemic anti-psoriasis drugs may be contraindicated: Ciclosporin A in hypertension, methotrexate in liver disease, acitretin in dyslipidemia. In summary, the following can be said:

- Comorbidities influence the choice of therapy.

- Dermatologists have the ability to diagnose PsA early.

- Psoriasis is an independent cardiovascular risk factor.

- Many comorbidities continue to be underestimated, especially anxiety disorders and depression.

Source: Annual Swiss Psoriasis Day, 31 October 2013, Basel

Literature:

- Zink A, et al: Arthritis & Rheumatism 2006; 54(11): 3399-3407. DOI 10.1002/art.22193.

- Garcia-Doval I, et al: Arch Dermatol 2012 Apr; 148(4): 463-470. DOI: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2768.

- Ormerod AD, et al: Dermatology 2012; 224(3): 236-43. doi: 10.1159/000338572. epub 2012 Jun 1.

- Mrowietz U, et al: Arch Dermatol Res 2011; 303(1): 1-10.

- Mrowietz U, et al: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol 2013 Feb 26.

- Mease PJ, et al: Arthritis Rheum 2005 Oct; 52(10): 3279-3289.

- Mease PJ, et al: Arthritis Rheum 2004 Jul; 50(7): 2264-2272.

- Antoni C, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: 1150-1157. DOI:10.1136/ard.2004.032268.

- McInnes IB, et al: EULAR 2012, Abstract #OP0158.

- Gisondi P, et al: British Journal of Dermatology 2007; 157(1): 68-73.

- Boehncke WH, et al: BMJ 2010 Jan 15; 340: b5666. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.b5666.

- Hogan AE, et al: Diabetologia 2011 Nov; 54(11): 2745-54. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2232-3. epub 2011 Jul 9.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(1): 35-37