A “Special Session” at the ESMO Congress focused on meningiomas. Although these brain tumors are primarily treated surgically, higher-grade meningiomas that can grow invasively may require radio or systems therapy.

(ee) An introduction to the classification and molecular pathology of meningiomas was given by Prof. Christian Mawrin, MD, director of the Institute of Neuropathology at Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg, Germany. Meningiomas are the most common intracranial tumors: they account for 54% of all benign brain tumors, but also 1% of all malignant brain tumors. Women are two to three times more likely to be affected by meningiomas than men.

About 80% of meningiomas belong to the grade I tumor group, 20% correspond to grade II (atypical meningiomas), and less than 1% are grade III anaplastic tumors. The prognosis of meningioma disease is usually good, but grade II and grade III meningiomas in particular are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Recurrent meningiomas are at risk for invasive growth. A whole range of pathological subtypes are distinguished, e.g. angiomatous, fibromatous and secretory meningiomas of grade I.

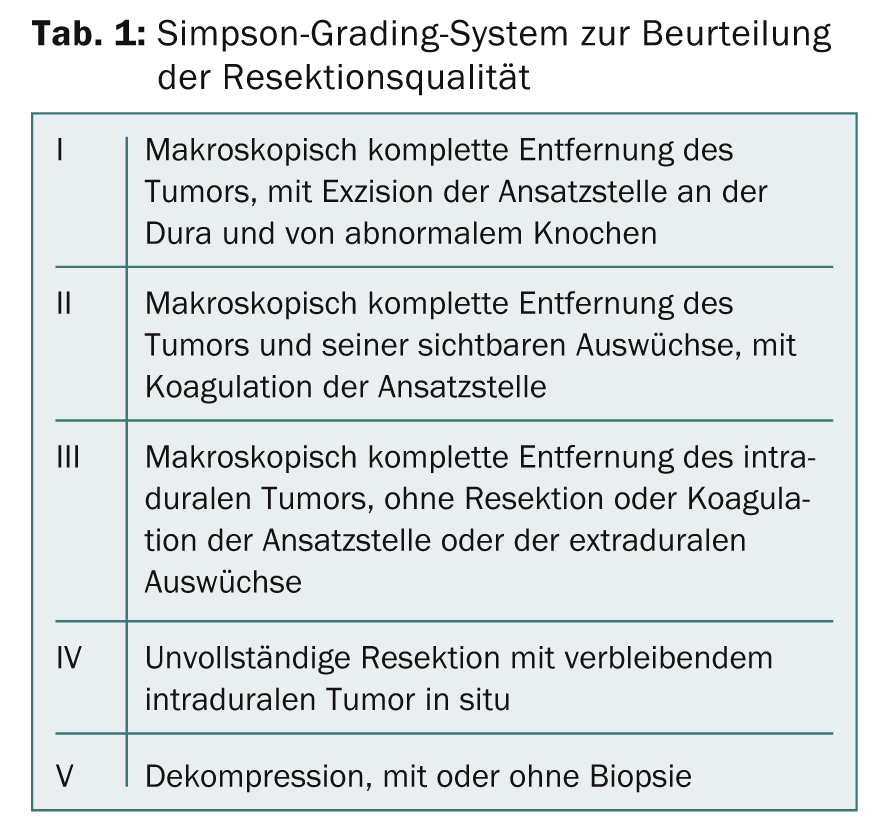

Classification according to Simpson grades

Based on the observation that patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NR2) frequently develop meningiomas, loss of the NF2 gene on chromosome 22q has been identified as the major genetic alteration leading to meningioma development. NF2 alterations are found in 40-50% of all sporadic meningiomas, and in the mouse model it has been shown that loss of NF2 is the initial step in the development of meningiomas. Progression of grade I meningioma to a more aggressive form is linked to inactivation of suppressor genes. In particular, alterations of the CDKN2A/CDKN2B genes on chromosome 9p play an important role.

Very important in the evaluation of meningiomas is the location: meningiomas in the convexity are more likely to have NF2 alterations, and meningiomas at the skull base, which recur more often than meningiomas of the convexity, are more often of the NF2 wild type.

After resection, meningiomas are graded according to the Simpson grading system (Tab. 1) . This dates back to 1957 and is still up to date! The grading is important for assessing the risk of recurrence: this is about 10% for Simpson 1, about 20% for Simpson 2, and even greater for higher Simpson grades.

Radiotherapy for meningiomas

Prof. Damien Weber, MD, Chief Physician of the Center for Proton Therapy, Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, provided information on the possibilities of radiotherapy. Meningiomas were once considered resistant to radiation, but radiotherapy is now considered an effective adjuvant treatment. For meningiomas of grade I and a Simpson resection ≥3, radiation after surgery improves tumor control. However, it is not yet clear when radiation should be given, i.e., whether immediately postoperatively or only at progression, and at what dosage. For this reason, the EORTC started a corresponding study in 2004.

For higher-grade meningiomas, most retreospective studies show better efficacy of radiotherapy at higher doses. For this reason, the EORTC is investigating adjuvant, postoperative high-dose radiotherapy for non-benign meningiomas in a phase II trial. Patients with incomplete resection (Simpson ≥3) are irradiated with 70 Gy. First results are expected in 2016.

Also open is the question of whether to irradiate grade II meningiomas after complete resection (Simpson 1). Several studies show that the recurrence rate is greater in unirradiated patients than in patients who received radiotherapy. However, radiotherapy is not recommended in most centers.

In a currently ongoing study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG), patients are divided into three risk groups: Low-risk patients (WHO grade I, all Simpson grades) are observed but not irradiated; intermediate-risk patients (WHO grade II, Simpson ≤3; WHO grade I with recurrence) receive radiotherapy at 54 Gy; high-risk patients (all others) receive radiotherapy at 60 Gy. Results are currently pending.

Systemic therapy

Recurrent, progressive or metastatic meningiomas can no longer be treated with surgery or radiotherapy, explained Prof. Matthias Preusser, MD, Medical University of Vienna. To date, there have been few studies of systemic therapies, and little is known about biomarkers and targets. The few existing data on targeted agents come mostly from case reports, smaller uncontrolled studies, and retrospective analyses. To date, no benefit of interferon-alpha, octreotide analogues, mifepristone, megestrol acetate, imatinib, erlotinib, or gefitinib has been demonstrated. Possibly effective substances are:

- Bevacizumab; It shows low response rates in smaller studies. Currently, the use of bevacizumab in meningiomas is being investigated in two studies.

- Sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, showed efficacy in a recent phase II trial in 36 patients with high-grade meningiomas and multiple recurrences [1]. 42% of patients were still progression-free six months after therapy (primary endpoint). Based on these results, the authors propose to conduct a randomized trial.

- A Phase II trial of vatalinib, another tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was also recently completed.

- Trabectedin (Yondelis®), an active ingredient derived from a sea squirt (tunicate), is already approved for the treatment of sarcoma and ovarian cancer. Further studies are underway on several other tumors. Following a promising in vitro study, an EORTC trial is now starting in 2015 in more than 30 centers in Europe in patients suffering from recurrent grade II or III meningioma who have run out of local treatment options.

Source: European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, September 26-30, 2014, Madrid.

Literature:

- Kaley T, et al: Phase II trial of sunitinib for recurrent and progressive atypical and anaplastic meningioma. Neuro-Oncology 2014; 0: 1-6.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2014; 2(9): 27-28.