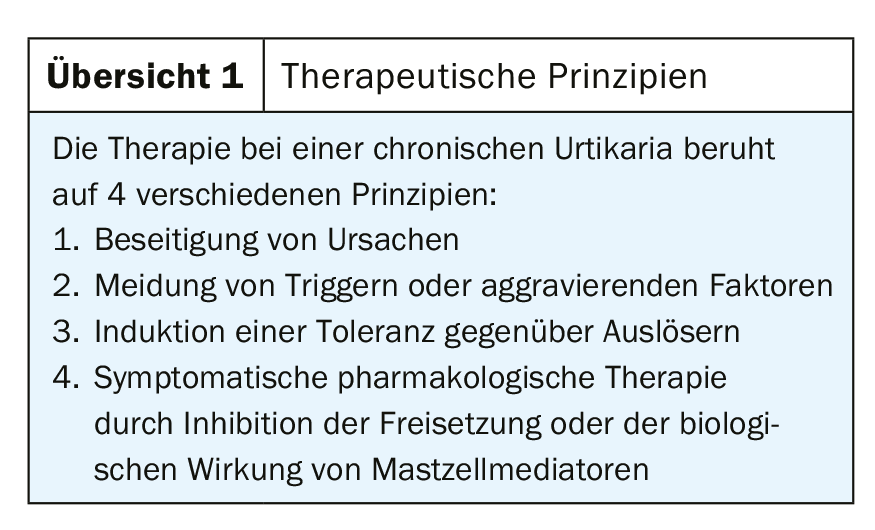

In addition to elimination of causes, avoidance of triggers, and induction of tolerance, pharmacologic treatment is the fourth pillar in disease management of this distressing skin disorder. Several 2nd generation antihistamines are available, as well as several other treatment options.

While acute urticaria (duration <6 weeks) with a lifetime prevalence of between 12 and 24% is a common disease but usually presents few therapeutic problems, this may well be the case with the rarer chronic urticaria (CU), for which a 1-year prevalence of up to 0.8% is reported [1,2]. Data on how often acute urticaria progresses to a chronic form are unfortunately scarce. The following comments are based on the current European guideline on urticaria, the other available literature and our own experience in the care of patients with CU [3]. They also apply to those chronic angioedema that are not due to ACE inhibitor use or C1 inhibitor disorders.

Clinical differentiation and etiological clarification

The arbitrary distinction between the two forms based on their population duration of less than or more than 6 weeks has implications regarding diagnostic measures to clarify their aetiology. In the case of a single episode of acute urticaria without an anamnestic trigger, allergological examinations are not very useful, especially if they persist for more than 24 hours. In contrast, patients affected by chronic urticaria in particular question the cause of the disease. In this context, past experience with often very extensive diagnostics has sobered us, so that only the determination of inflammatory parameters such as CRP and a blood count are still recommended as untargeted examinations. Further measures with regard to chronic inflammation of the teeth, upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract are usually made dependent on correspondingly described complaints. These examinations may lead to at least partially effective causal treatment or, as in the case of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis discovered for the first time, may give rise to organ function checks. The detection of so-called autoreactive urticaria with mast cell-activating autoantibodies initially provides a possible answer to the question of the origin of the disease, but implications in terms of a causal therapy result from this only in individual patients.

In addition to appropriate investigations, intensive history taking cannot be emphasized enough, as it is also important to distinguish chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), with its wheals seemingly arising out of nowhere, from the inducible forms, in which physical factors usually play a role. On the one hand, several forms of physical urticaria may coexist in a single patient; on the other hand, it not infrequently occurs together with chronic spontaneous urticaria. This differentiation in the individual patient is important in order not to disregard crucial avoidance strategies. Furthermore, when the patient makes a blanket statement about the lack of effect of symptomatic therapy, one should take into account its different effects on the individual forms of urticaria. This is true, among other things, of associated delayed pressure urticaria.

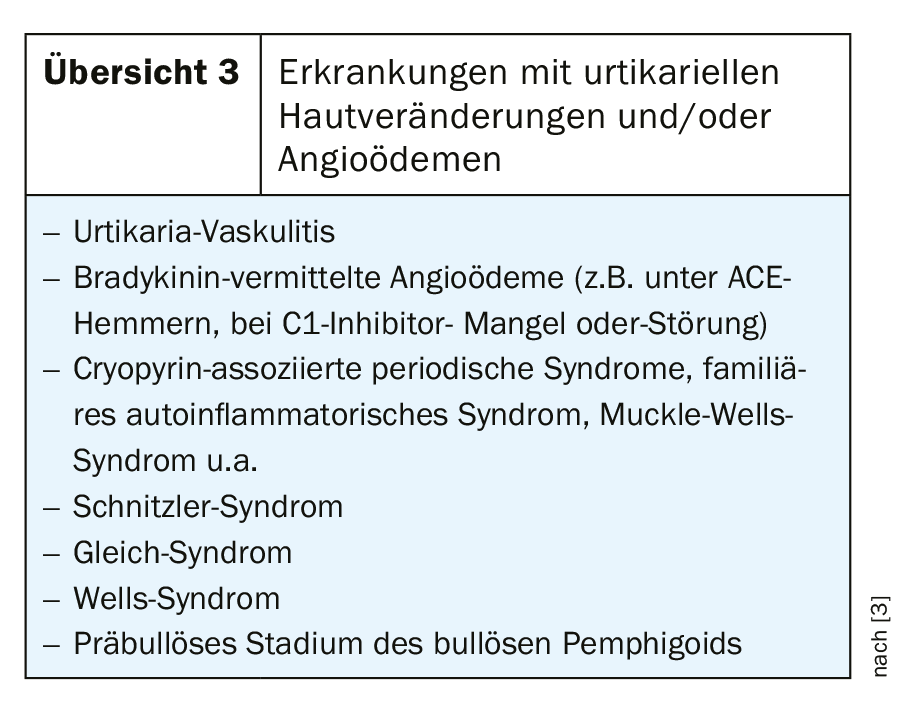

A further indication for the diagnostics and therapy to be adopted results from the Differential diagnosis of urticarial skin lesions as seen in a number of very different Diseases can occur (Overview 3). The duration of the individual efflorescences (longer than 24 hours?) and accompanying symptoms (fever, bone and joint pain, or abdominal cramps) are important. In many cases, a sample biopsy from a wheal is required for further clarification.

Diagnostic algorithms can be found in various publications [3,4].

Therapy approaches

1. elimination of causes

Unfortunately, even very extensive diagnostics in the past have only led to the identification of causes that can be therapeutically influenced in a rather small proportion of patients. Furthermore, eradication of Helicobacter pylori or intestinal parasites, for example, does not regularly lead to the disappearance of urticaria within a reasonable period of time. The evaluation of corresponding therapy studies is complicated by contradictory results, occasional methodological weaknesses, and the fact that the disease has a not inconsiderable tendency to spontaneous healing (see below). The decision to carry out appropriate treatment should therefore be made on an individual basis. If a link can be identified anamnestically between CSU activity and physical or emotional distress, this should prompt a search for ways to reduce it. On the other hand, other treatment options are recommended for cholinergic or exertional urticaria to avoid inactivation.

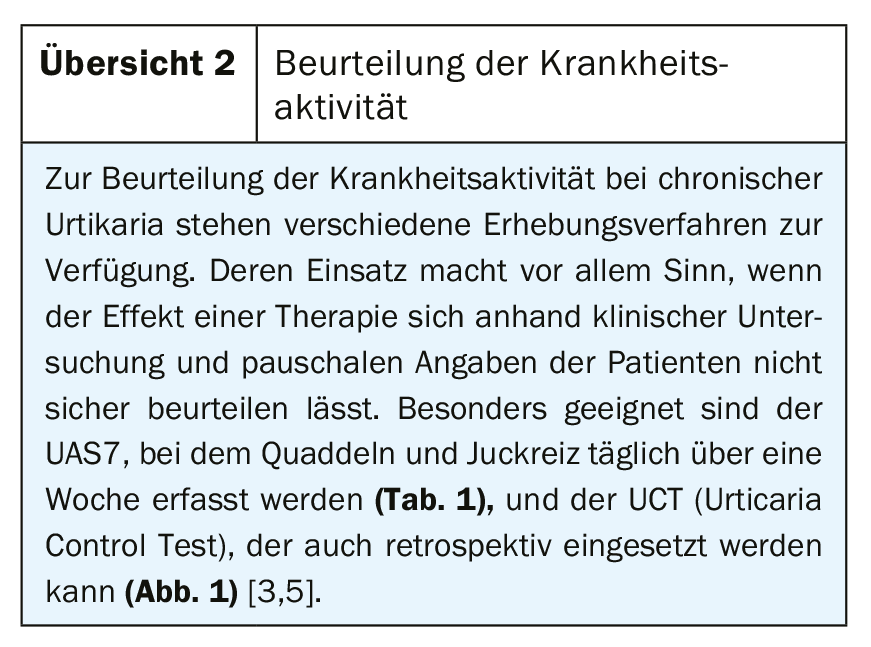

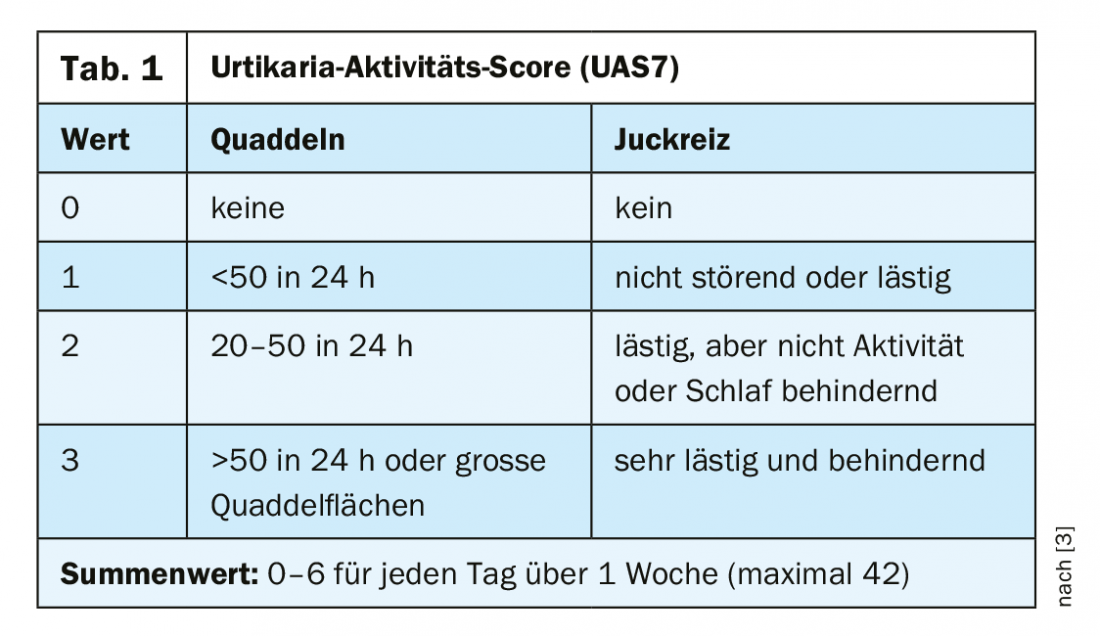

The value of a so-called low pseudoallergen diet, which was used more frequently in the past, or a low histamine diet is controversial. A trial meets the need of some patients, but then should only be done under good symptom control (UAS7) and for at least 2-3 weeks.

2. avoidance of aggravating factors

Affected patients should be advised that consumption of alcohol, use of NSAIDs, or heat (sunbathing, sauna) may lead to exacerbations of chronic urticaria. The same applies to (febrile) infections. Knowledge of such correlations is often helpful to patients who are concerned about acute exacerbations of their disease.

3. tolerance induction

Their overall significance is low and still most likely in solar urticaria when symptomatic pharmacological therapy is not sufficient. The effect is based on a temporary insensitivity to the original trigger and therefore requires continuous re-exposure. In contrast, this often makes therapy for cholinergic or cold contact urticaria impractical.

4. pharmacological therapy with inhibition of the release or action of mast cell mediators.

Since the clinical manifestations of urticaria are primarily due to the action of released histamine at the so-called H1 receptors of vessels and nerves, the use of appropriate antagonists is the preferred therapeutic approach. The mechanism of the so-called antihistamines is based on preferential binding to inactive H1 receptors and stabilization of this state. This also explains the better clinical effect of regular intake compared to on-demand medication. However, the latter makes sense if, in the case of physical urticaria, it is foreseeable for the patient that a corresponding exposure, e.g. to cold, is imminent. Due to pharmacodynamics, in this case it is recommended to take 1-2 hours before.

First-generation sedating antihistamines should no longer be used in the treatment of chronic urticaria because of their side effects. In this case, clemastine, which is available for parenteral administration, is only of importance in acute urticaria.

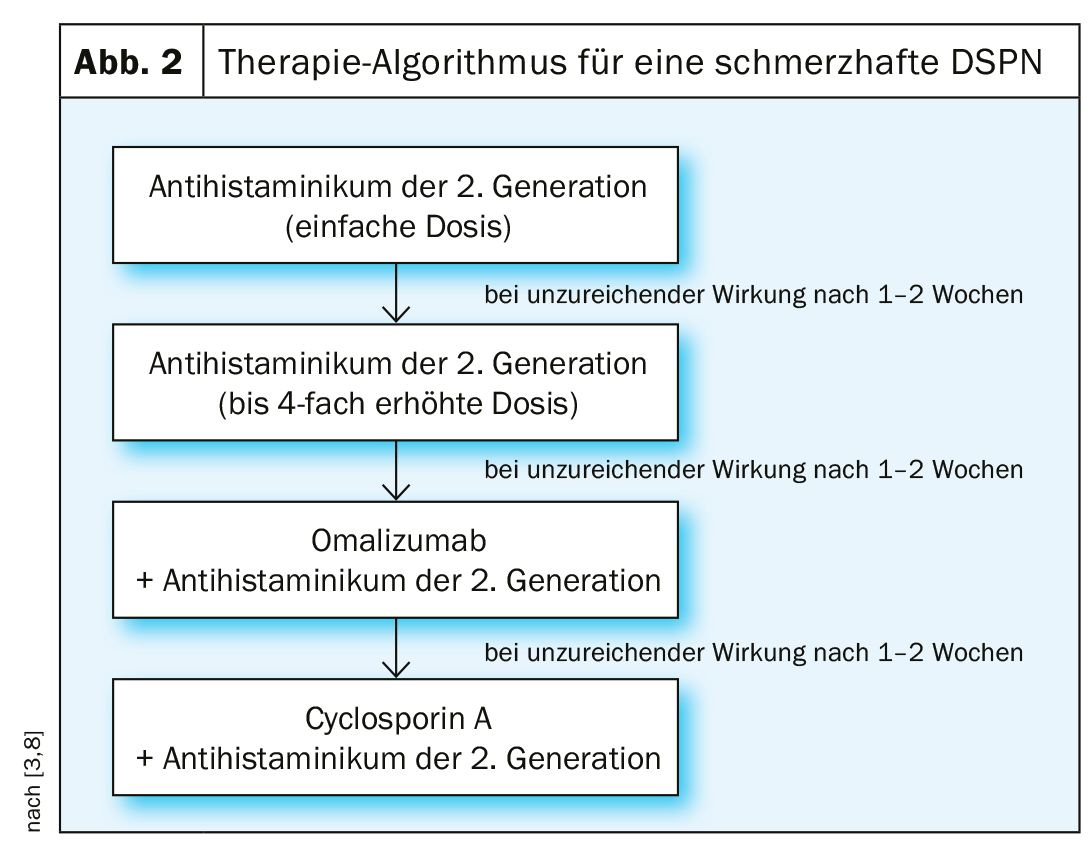

2nd generation antihistamines: Due to their better spectrum of side effects, the so-called 2nd generation antihistamines are to be preferred. In Switzerland, cetirizine or levocetirizine, loratadine or desloratadine, fexofenadine and bilastine are available. Levocetirizine is an enantiomer of cetirizine normally present as a racemate and desloratadine is a natural metabolite of loratadine. Therefore, the effect and potential side effects are largely identical. Noticeable sedation is most likely to be observed in individual patients with cetirizine or levocetirizine. Usually treated with a single dose taken 1 time daily, often responding to itching rather than redness or swelling. Sometimes patients report different efficacy of individual preparations, without there being any reproducible pattern in this respect or any pharmacological explanation for such differences. Therefore, a change of preparation is occasionally considered if the effect is not sufficient. If there is no sufficient symptom control within 1-2 weeks, an increase to double to four times the dose is recommended (Fig. 2) . Experience has shown that a regular distribution of the dose is not necessary; instead, administration 2× daily seems to be sufficient. Further increase beyond the quadruple dose is not recommended in the current guideline. The same applies to the combination of several antihistamines. Only for patients with severe hepatic or renal dysfunction is a dose reduction recommended for loratadine or cetirizine and fexofenadine. Due to lack of experience, the manufacturer does not recommend the use of bilastine for either patient group; thus, some caution is generally recommended in patients with such dysfunctions if dose increases are being considered.

Omalizumab: If acceptable disease control cannot be achieved even with this level of the therapeutic logarithm, the administration of omalizumab is the drug of choice. This drug, after its original use in bronchial asthma, is now also approved for protracted CSU as an adjuvant for insufficient response to H1 antihistamines. Typically, 300 mg is given every 4 weeks with the possibility of dose reduction to 150 mg. Unlike in bronchial asthma, this dose in chronic urticaria is independent of total serum IgE concentration and body weight. Strikingly, many patients observe a regression of itching and wheal formation already a few days after the first injection, so that they can reduce or stop taking the antihistamine, whereas the response especially of autoreactive chronic urticaria may be delayed. Other patients continue to require an additional antihistamine to adequately control their symptoms. If complete symptom freedom persists even under a reduced omalizumab dose, we usually extend the injection intervals by one week at a time and terminate therapy if no renewed symptoms of disease occur even after 8 weeks. However, should a relapse occur down the road, the drug can be used again without the expectation of a limited response. Ligelizumab, another anti-IgE antibody, appears to be even more effective than omalizumab in patients with overall more difficult-to-treat (e.g., autoreactive) CSU, but is not yet available [6].

Cyclosporin A: In case of treatment failure also of omalizumab, the use of cyclosporin A can be considered. However, this is an off-label use. Various studies have demonstrated the efficacy of this drug at doses between 3 and 5 mg/kg body weight per day. In addition to its immunosuppressive effect, which is likely to be involved in mast cell-activating autoantibodies, cyclosporine A also has a direct effect on mediator release from mast cells. When using this drug, the appropriate preliminary and control examinations as well as contraindications must of course also be observed in the CSU.

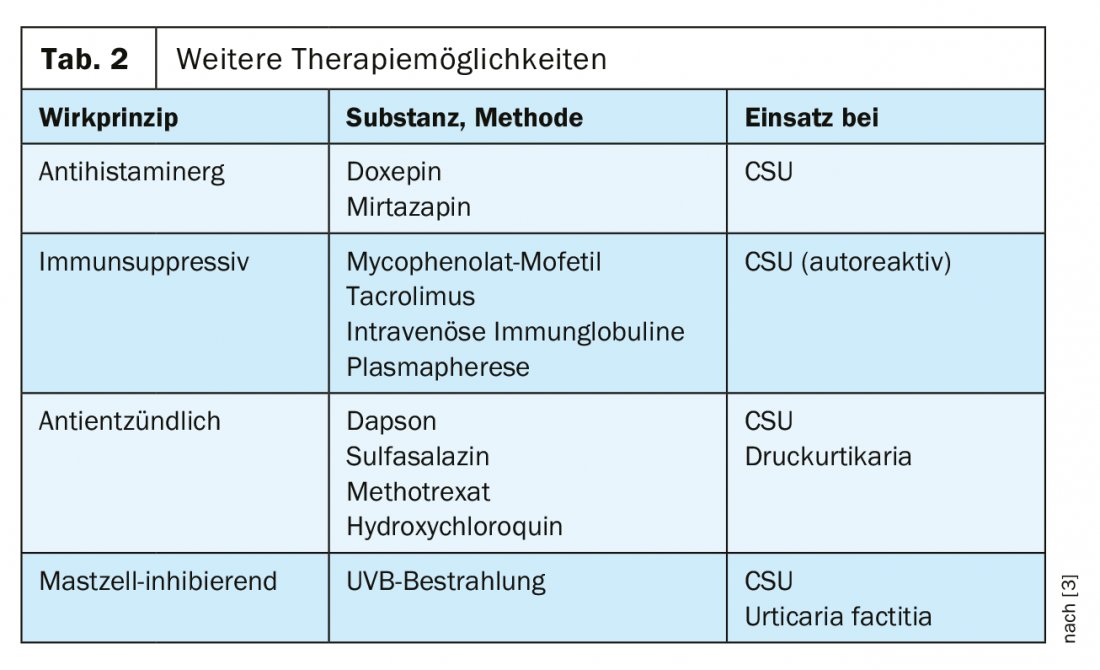

Other options: Leukotriene antagonists such as montelukast listed in previous treatment algorithms have low levels of evidence regarding their efficacy in CSU, so they are no longer generally recommended as adjuncts to antihistamines. In the case of refractory chronic urticaria, other forms of therapy may be considered, although the evidence of their efficacy, supported by publications, is limited. Nevertheless, their use in CSU or inducible urticaria will be considered in refractory courses (Table 2) . Systemic glucocorticosteroids have their place at most in the treatment of an otherwise uncontrollable exacerbation of the disease, where they can be administered as a short-duration burst of max. 10 days can be applied.

Course-adapted treatment strategy: If complete control of urticaria is achieved with one of the measures listed, therapy should be interrupted after 3-6 months in order to be able to record the natural course of the disease and thus also a possible spontaneous remission. Unfortunately, however, epidemiologic data on the spontaneous course of CU are limited and therefore quite divergent: in a Dutch study, 47% of patients with CSU were free of symptoms after 1 year. In contrast, healing occurred less frequently in chronic inducible (physical) urticaria [7]. The concomitant presence of physical urticaria may therefore substantially impair the achievement of the desired freedom from manifestations. Even when symptoms of chronic spontaneous urticaria disappear under an antihistamine, patients may well report persistence of their urticaria factitia or delayed pressure urticaria. In this case, an extension of therapy with substances from Table 2 or the use of omalizumab can be considered. Strictly speaking, however, the latter is then an off-label use.

In the treatment of children, the problem arises that, according to the official approval, the use of second-generation antihistamines is only possible from the age of 6 or 12. Only dimetind, which belongs to the first generation, has an approval for the first year of life. However, the older preparations (clemastine and dimetindene) have a lower safety profile compared with the second-generation antihistamines. Therefore, children should be treated with 2nd generation antihistamines in the same way as adults, adjusted for weight and age. When selecting the individual preparation, the availability in liquid form or as a rapidly dissolving tablet then also plays a role. The aforementioned therapeutic alternatives, such as increasing the dose of the antihistamine or the administration of omalizumab or cyclosporin A, have not been well studied with regard to urticaria.

Treatment of children, during pregnancy and lactation

At least for loratadine and to a lesser extent for cetirizine, there is ample experience in their use during pregnancy and lactation, so that at least these two antihistamines should be preferred. No safety studies are available on higher doses of antihistamines in pregnancy, which must at least be considered. On the other hand, there is no evidence of a teratogenic effect of omalizumab and cyclosporin A so far. Against this background, the current guideline recommends the cautious use of the same treatment algorithm in pregnant but also breastfeeding women after a good risk-benefit assessment. In any case, it must be taken into account that breastfed infants may also show sedation and thus, for example, weakness in drinking when the mother takes first-generation antihistamines.

Take-Home Messages

- Chronic urticaria without anamnestic evidence does not require extensive etiologic workup.

- Concomitant physical urticaria should be considered as part of the therapy of chronic spontaneous urticaria.

- Sedating first-generation antihistamines should be avoided.

- If the effect of a single-dose antihistamine is inadequate, a rapid increase in dose is recommended. If the desired effect fails to appear, omalizumab can be used.

Literature:

- Antia C, et al: Urticaria: A comprehensive review: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 79(4): 599-614.

- Antia C, et al: Urticaria: A comprehensive review: Treatment of chronic urticaria, special populations, and disease outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 79(4): 617-633.

- Zuberbier T, et al: The EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy 2018; 73(7): 1393-1414.

- Bernstein JA, et al: The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133(5): 1270-1277.

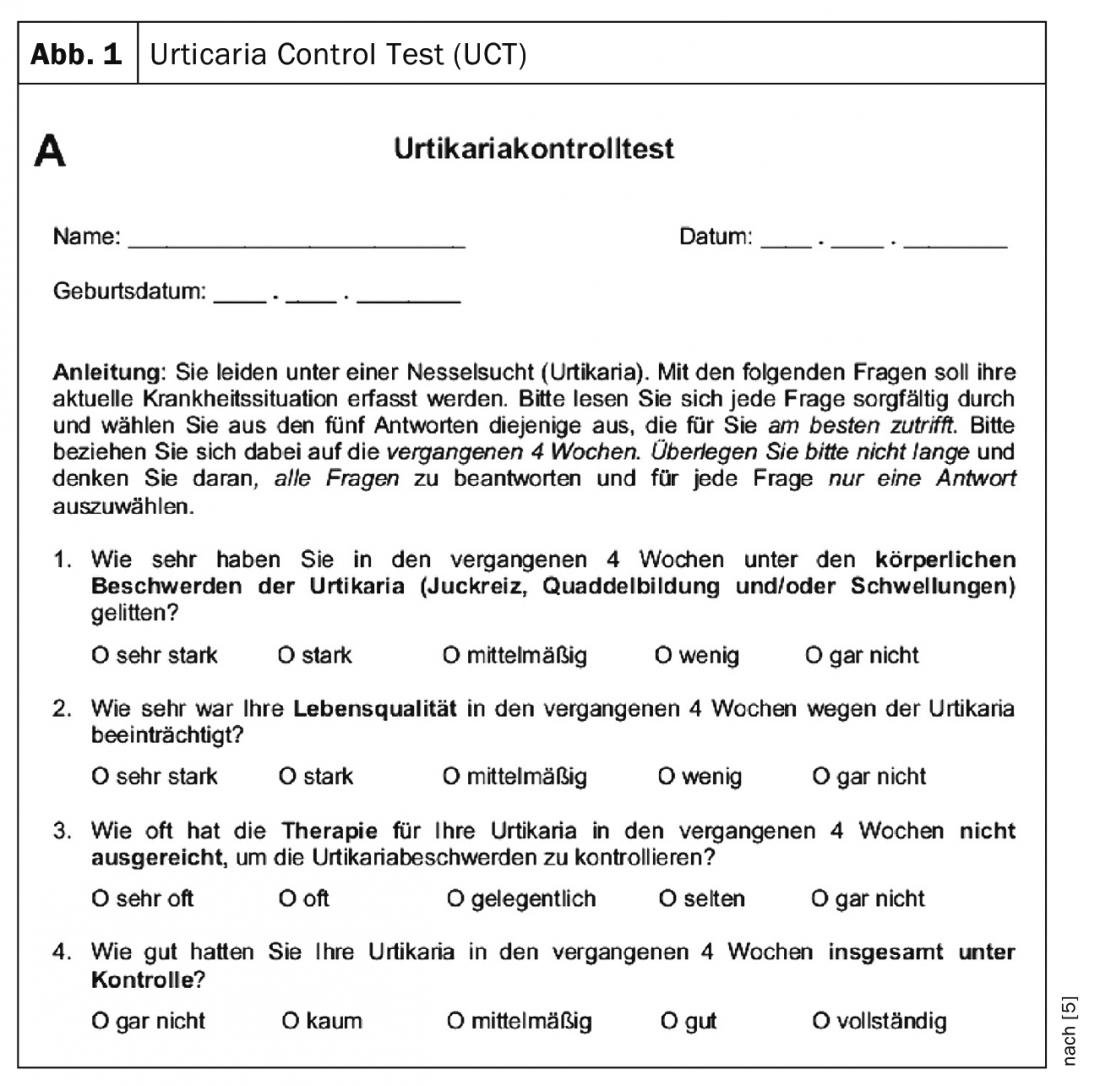

- Weller K, et al: Development and validation of the Urticaria Control Test: a patient-reported outcome instrument for assessing urticaria control J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133(5): 1365-1372.

- Maurer M, et al: Ligelizumab for Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. N Engl J Med 2019; 381(14): 1321-1332.

- Kozel MM, et al: Natural course of physical and chronic urticaria and angioedema in 220 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 45(3): 387-391.

- Spertini F, et al: Urticaria management in primary care. Switzerland Med Forum 2017; 17(32): 660-664.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(6): 8-11