Sarcomas are rare malignant connective tissue tumors. Therapy is multidisciplinary and should be performed at sarcoma centers. In Switzerland, all sarcoma disciplines have organized themselves on a national level (www.sarcoma.ch). Here, therapy guidelines are published, a registry, a cohort study and a tissue bank are established. Surgical complete tumor removal represents the most important therapeutic measure, both for bone and soft tissue tumors. Overall, limb-preserving surgery is performed whenever possible; in the case of bone tumors, reconstruction is preferably performed with a (modular tumor) endoprosthesis or in combination with an allograft. Radiotherapy is often used for soft tissue tumors, especially when the tumor is adjacent to neurovascular structures to improve local control. Additive systemic chemotherapy, usually doxorubicin-based, is used primarily for osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and metastases to improve prognosis.

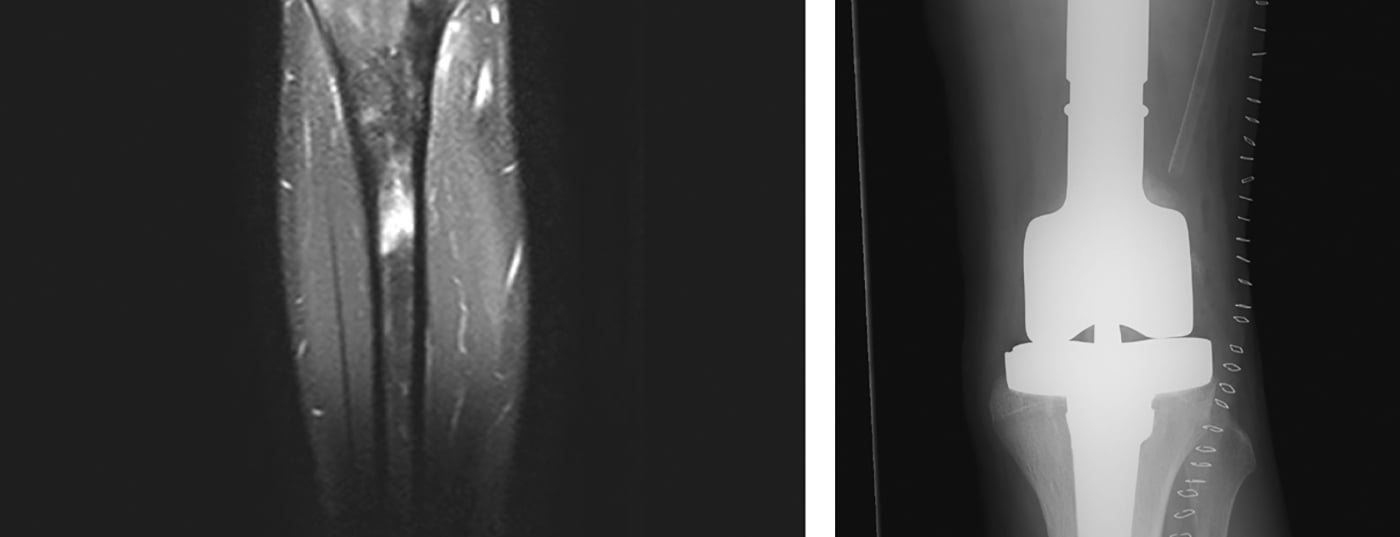

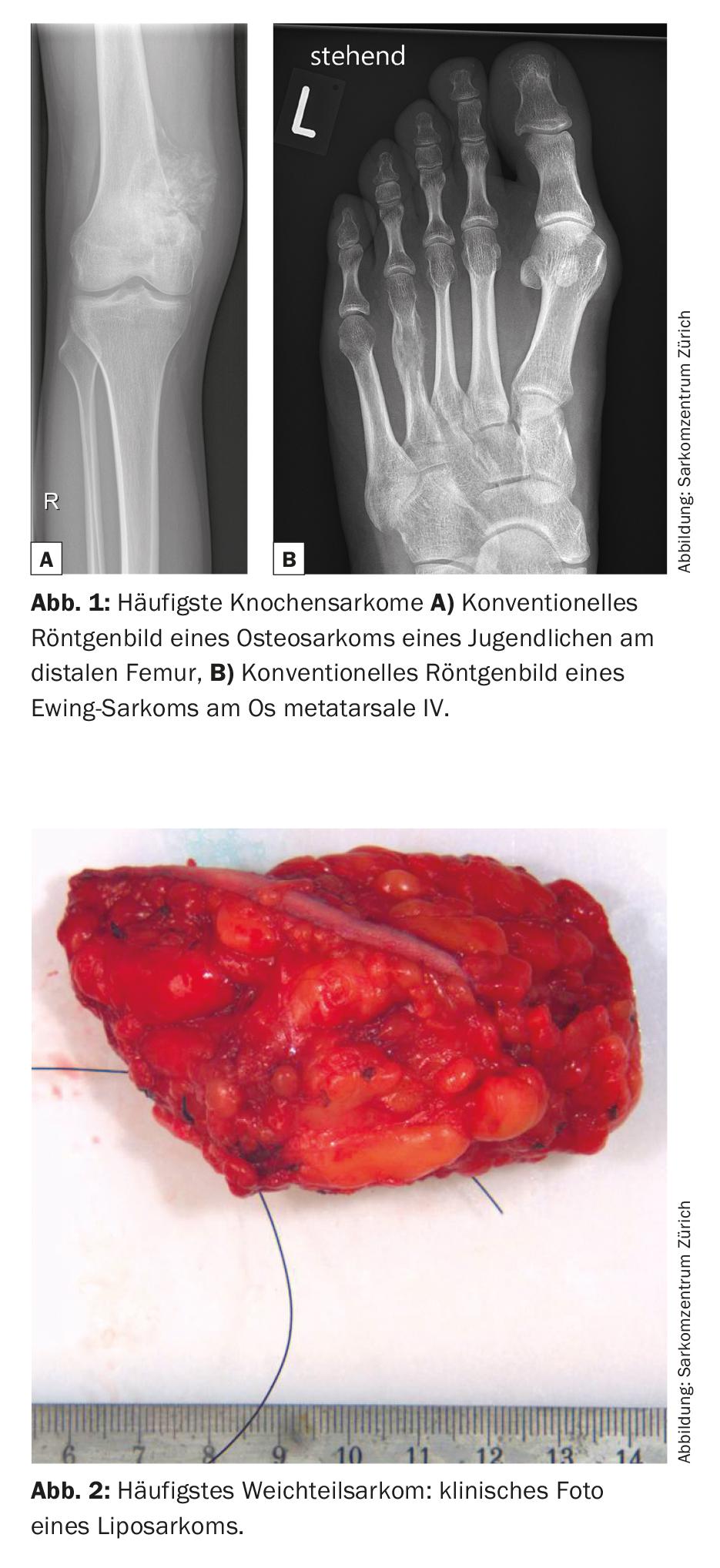

Sarcomas are rare malignant connective tissue tumors that account for 6% of all childhood cancers [1]. There are numerous subtypes, over 50 in total, which can generally be divided into bone and soft tissue sarcomas. In this context, metaphyseal developing osteosarcoma and diaphyseal developing Ewing sarcoma represent the most common bone sarcomas, while liposarcoma is one of the most common soft tissue sarcomas (Figs. 1 and 2) .

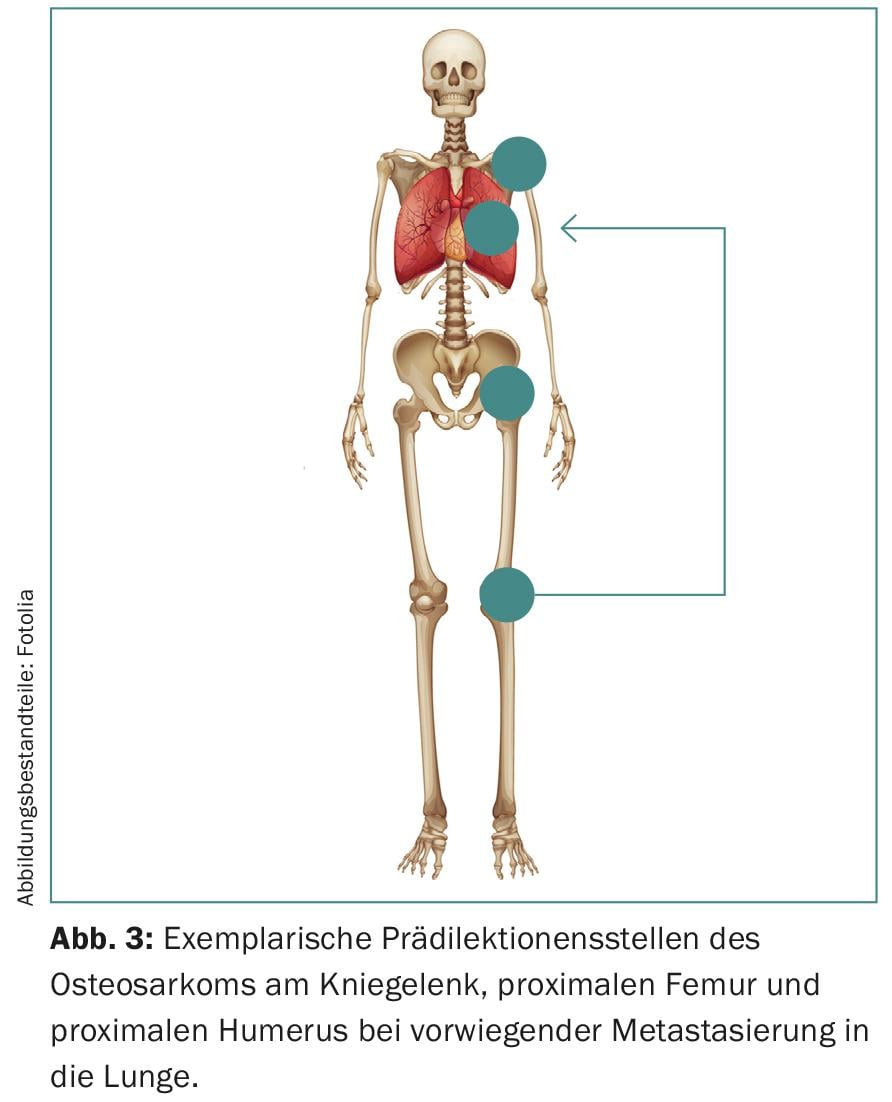

Furthermore, sarcomas show predilections for certain age groups and anatomical structures (Fig. 3) . Thereby, they manifest with a bimodal age distribution mainly in extremities and in the axial skeleton. The knee region of adolescents is particularly affected, although the head, neck and abdomen may also be affected.

Diagnostics

In most cases, the diagnosis is made on the basis of an incidental finding, although swelling and pain may occasionally occur. The latter classically have a local, progressive, predominantly nocturnal character that cannot be influenced by NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) [2]. In the clinical examination, the tumor tissue with overlying skin and adjacent lymph nodes should first be inspected and palpated locally. Subsequently, a search for metastases can be extended to the thyroid, abdomen, prostate or mamma. Systemic B symptomatology is very rare.

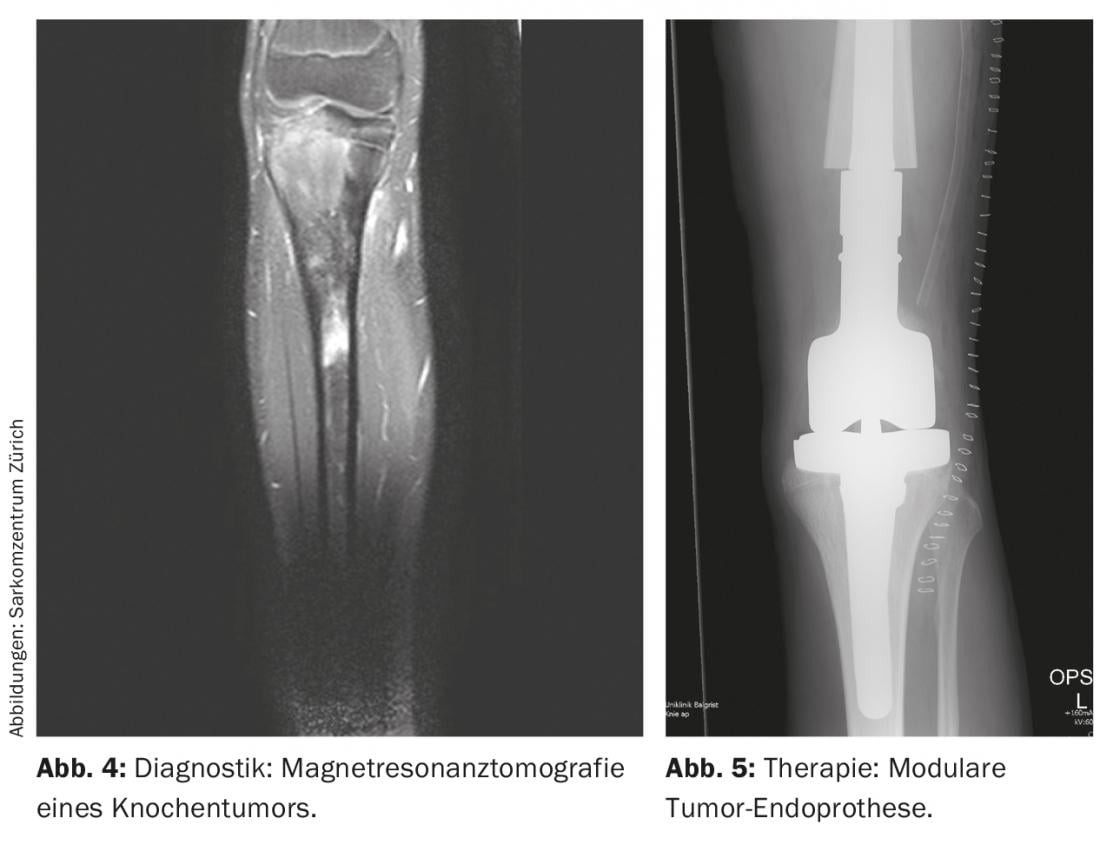

Radiologic imaging is used to localize the tumor, which includes local and thoracic two-plane radiographs and, if necessary, CT (computed tomography), local MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) (Fig. 4 ), and systemic Tc (technetium) skeletal scintigraphy or, alternatively, PET-CT. In general, it should be noted that conventional radiographs of long bones should always image both adjacent joints. In addition, the lungs are also examined because they are the most frequently affected by metastases, in about 10% of cases. At diagnosis, osteosarcomas and Ewing’s sarcomas classically exhibit a periosteal spur known as a Codman triangle, and onion-skinned periosteal calcifications. Basically, the size (≤ or >10 cm), location (epi- or subfascial), and metastatic status of the tumor should be recorded. In addition, routine laboratory chemistry tests and determination of lactate dehydrogenase and alkaline phosphatase are helpful in ruling out generalized disease and estimating disease burden, although they are relatively nonspecific.

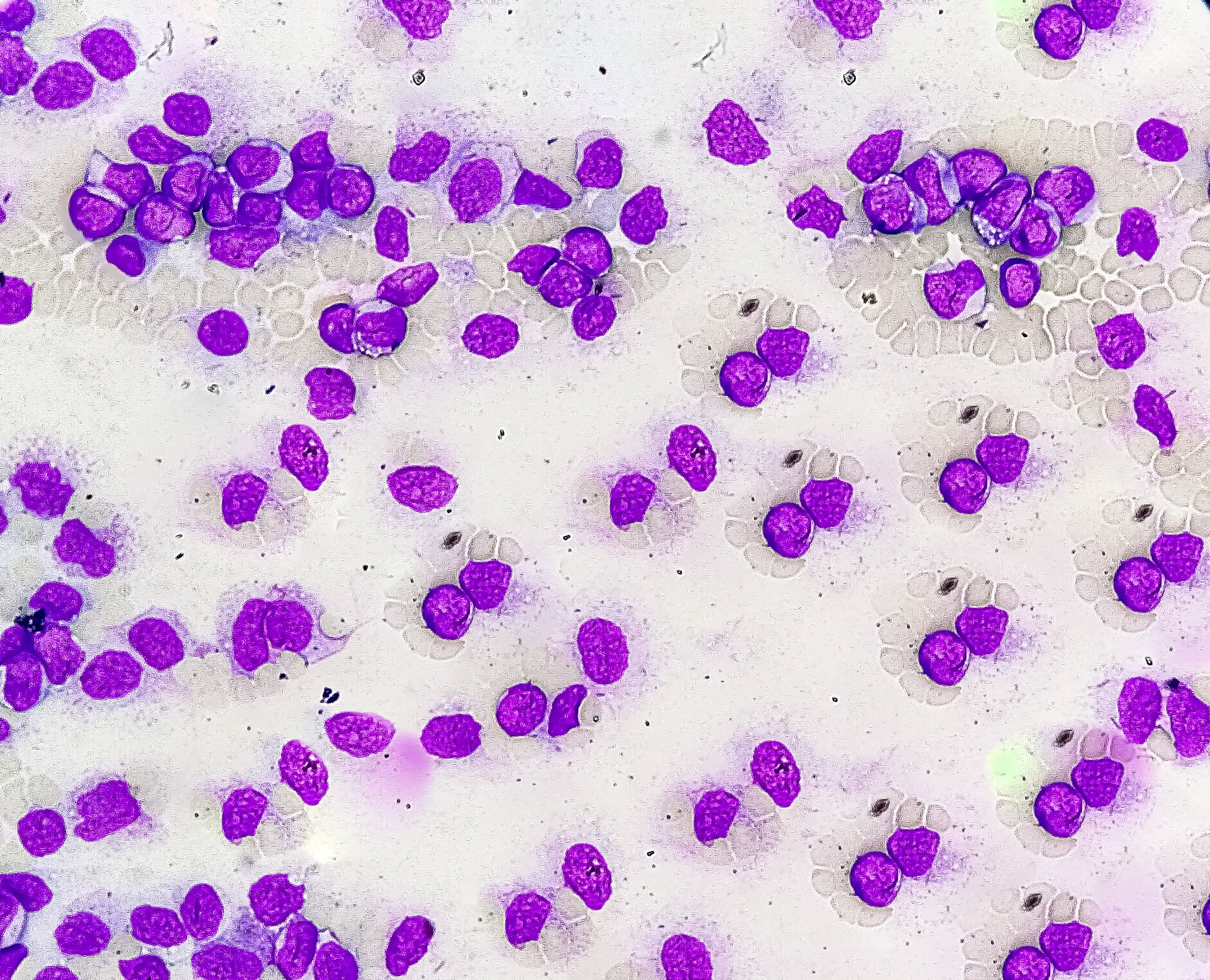

Finally, a nowadays often minimally invasive CT- or US-guided biopsy is able to provide information about the specific sarcoma subtype by microscopic, immunological and molecular genetic investigations. Care is taken to select the biopsy tract so that it can be removed in toto in any subsequent surgery. If a punch biopsy yields equivocal results, an open biopsy is performed. Hematomas are avoided due to the risk of dissemination by performing muscle fascia closure or redon insertion. Intrainterventionally, always prepare a fresh evidence on ice. In addition, a bacteriological examination should be performed to be on the safe side. Therefore, pre-interventional antibiotic administration should be discouraged to avoid complicating examination results and resistance-targeted treatment.

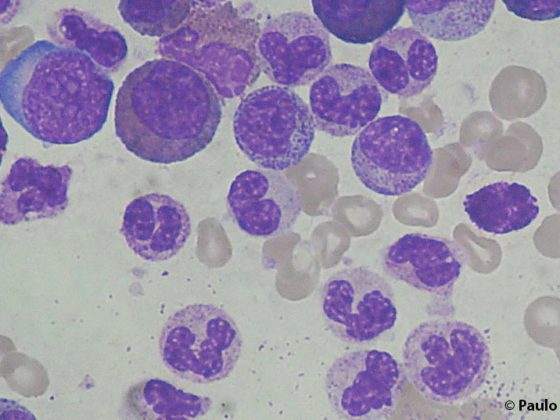

The paraffin-embedded tissue block is used for histological classification, for which there are several options. Depending on the classification, specific molecular biological examinations then follow. The six-stage (IA-IIIB) staging according to Enneking (Musculoskeletal Tumor Society) takes into account metastases (no vs. yes), histologic grade (low vs. high), and anatomic tumor size (intra- vs. extracompartmental). In the somewhat more detailed seven-stage (IA-IVB) staging of the AJCC (American Joint Commission on Cancer), lymph node involvement is indicated additively.

Therapy

The elaborate therapies in highly specialized sarcoma centers lead to relatively good results in the long-term treatment of localized sarcomas with 5-year survival rates of up to 75% [3]. In contrast, survival rates for metastatic sarcomas are only about 25%. As these outcomes have plateaued for over a decade, sarcomas continue to be the subject of diverse international research projects to gain a better molecular genetic understanding and thus define new therapeutic options.

Therapy requires an interdisciplinary team of orthopedic tumor surgeons, radiologists, oncologists, radiologists, and pathologists. Based on its demographic entities, each patient and also each sarcoma subtype, similar to hematopoietic neoplasms, should receive unique multidisciplinary therapy adapted to the biological changes, often multimodal. Overall, the curative therapeutic goal in localized tumor is surgical complete tumor excision. Especially in bone sarcomas, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are used additively to reduce (micro)metastases and local recurrences. Soft tissue sarcomas are very often treated by combination therapy, with radiotherapy either preceding or following surgery. A palliative approach must be considered as soon as metastases are present at diagnosis, which affects about 10% of patients. Guidelines for evaluation, diagnosis, treatment options and follow-up have been established by the Swiss National Sarcoma Advisory Board and published on the website www.sarcoma.ch.

Operation

Since its introduction more than 30 years ago, complete surgical tumor removal has emerged as the main therapeutic option (Fig. 2), and has the best “therapy response” of all therapeutic modalities. In particular, it can be used as a singular therapy for small (<5 cm), completely excised, and low-grade tumors of the soft tissues [4]. The nature of the resection margin is critical to the recurrence rate, which is 100% for an intralesional margin, <50% for a marginal margin, and <10% for a wide (>1 cm) margin. If complete removal of tumor tissue is not achieved at primary surgery, secondary surgery should be considered in terms of post-resection rather than substituting other treatment options. In addition, curative metastasectomy remains controversial.

The choice of the most appropriate surgical method is based primarily on tumor classification and location. As a rule, limb-preserving surgical techniques are preferred whenever possible. These include initial en bloc tumor resection and subsequent reconstruction. The aim is to achieve a tumor resection equivalent to classical amputation while preserving function as physiologically as possible. With regard to axial tumor localizations, CT-guided navigation can be helpful in sparing important neurovascular structures, especially in difficult pelvic operations. Nevertheless, the prognosis of axial tumors is worse than that of the extremities due to difficult resectability [5].

Allografts and/or modular (tumor) endoprostheses are commonly used (Fig. 5) [6]. Allografts have become more available through bone banking in recent years, provide an adequate soft tissue mantle, and result in osteointegration into the body after several years. However, there is not only an increased risk of fracture, but also the risk of pseudoarthrosis due to ossification of the graft-host zone lasting up to one year. Endoprostheses are primarily used for metaphyseal tumors with necessary joint and/or epiphyseal resection to preserve range of motion and compensate for leg length discrepancies. They offer the advantage of relatively rapid postoperative full weight-bearing with good range of motion. However, there are the usual disadvantages of prostheses, which can loosen in about 5-10% of patients. In this regard, they show 5- and 10-year survival rates of approximately 80% and 70%, respectively. Compared to prosthesis implantation alone, an allograft-prosthetic composite offers the advantage of better soft-tissue anchorage with a lower risk of loosening and is otherwise able to combine the other advantages and disadvantages of both methods.

Amputation is performed in less than 10% of cases and is now used as a last resort because it does not result in better survival rates than adequately performed limb-preserving surgery [7]. It is a valid therapeutic option especially for non-reconstructable recurrences affecting neurovascular structures and thus limiting function. In this regard, today’s prosthesis fitting offers good and diverse possibilities, especially for amputation stumps that are as distal as possible. In addition, a Van Ness reverse plasty is an intercalary limb-shortening amputation in which the lower leg, including the foot, is fixed to the proximal limb. This allows the upper ankle joint to take over the knee joint function and better control a prosthesis.

Chemotherapy

Systemic chemotherapy may be administered additively during surgery, either preoperatively or postoperatively, or both depending on the tumor type. This usually consists of a doxorubicin-based combination [8], with doxorubicin acting as an intercalant to impair DNA synthesis and lead to apoptosis via free radical formation. In the case of osteosarcoma, this usually consists of multiple cycles of doxorubicin, methotrexate, and cisplatin. In addition to osteosarcomas, Ewing sarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, and metastases are often treated with chemotherapy. However, their therapeutic and thus prognostic effect is controversial, especially in soft tissue sarcomas. Due to the non-negligible side effects such as nephro- or cardiotoxicity, a risk-benefit analysis should therefore be performed in each individual case. In addition, the application is best done in the context of clinical trials.

It can be given preoperatively, neoadjuvantly, or postoperatively, adjuvantly, for about seven months. The advantage of neoadjuvant use is tumor mass reduction, treatment of radiologically invisible micrometastases, and prognostic relevance. Micrometastases are found in up to 80% of cases, especially in osteosarcomas. Prognosis critically depends on chemotherapy response and is reflected in the histologic necrosis rate (≥90% = good vs. <90% = poor) according to Salzer-Kuntschik.

Radiotherapy

Radiation therapy is another therapeutic option, especially for soft tissue sarcomas. It is able to reduce the recurrence rate, which is less than 10%. Whether this also affects metastasis and prognosis remains unclear. It is used primarily in large, deep, high-grade, incompletely excised, neurovascular, soft tissue, and metastatic sarcomas [9]. Generally, it leads to toxic double-strand breaks of cell DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) by free radicals and thus to apoptosis. Preoperative use is often preferred. This allows, on the one hand, a lower therapy dose of about 50 Gy (Gray) due to the more detailed contouring and the smaller volume and, on the other hand, a better functional long-term result. However, there is also an increased risk of reversible postoperative wound healing disorders. Adjuvant use, on the other hand, is more likely to lead to irreversible late complications such as lymphedema, fibrosis, joint stiffness, stress fractures, and post-irradiation sarcoma, so it is best to avoid it.

Other therapy options

In addition to the established standard therapies already mentioned, there are other therapeutic options whose efficacy or superiority has not yet been sufficiently proven by randomized controlled trials. These include locally regional hyperthermia, isolated hyperthermic limb perfusion, isolated limb infusion, and local catheter-based brachytherapy, and systemically monoclonal antibodies, bisphosphonates, stem cell therapy, and (photodynamic) nanotechnology [10].

Follow-up checks

In addition to the initial clinical follow-up, which varies depending on the procedure, the first clinical-radiological follow-up, including the results of the surgery, is performed three months postoperatively. local conventional X-ray and MRI examination of the tumor area as well as a thoracic CT to exclude metastases take place (see also www.sarcoma.ch). Because most recurrences or late metastases occur within the first two to three years, follow-up visits occur every three months at this time before semiannual consultations occur until the five-year follow-up. Subsequently, the scheme is adapted to one- to two-year controls.

Conflict of interest: the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Literature:

- HaDuong JH, et al: Sarcomas. Pediatr Clin North Am 2015; 62: 179-200.

- Miller MD, et al. Review of Orthopaedics.6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders 2012; 623-674.

- Kager L, et al: Primary metastatic osteosarcoma: presentation and outcome of patients treated on neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group protocols. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 2011-2018.

- Ferrone ML, Raut CP: Modern surgical therapy: limb salvage and the role of amputation for extremity soft-tissue sarcomas. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2012; 21: 201-213.

- Jentzsch T, et al: Expression of MSH2 and MSH6 on a Tissue Microarray in Patients with Osteosarcoma. Anticancer Res 2014; 34: 6961-6972.

- Moore DD, Luu HH: Osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res 2014; 162: 65-92.

- Grimer RJ, et al: Surgical outcomes in osteosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84: 395-400.

- Whelan JS, et al: EURAMOS-1, an international randomised study for osteosarcoma: results from pre-randomisation treatment. Ann Oncol 2015 Feb; 26(2): 407-414.

- Yang JC, et al: Randomized prospective study of the benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 197-203.

- Wunder JS, et al: Opportunities for improving the therapeutic ratio for patients with sarcoma. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8: 513-524

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(5): 18-21.