When it comes to treating chronic wounds, primary care physicians often reach their limits. Not least because interaction with those affected is often difficult. An interdisciplinary, multiprofessional, and transsectoral treatment regime can help.

Chronic wounds, in addition to rare pathologies, are found in three major groups: Decubitus, venous leg ulcer, diabetic foot syndrome (DFS). Decubital ulcers occur in elderly, immobile patients due to prolonged elevated pressure and are therefore predominantly interpreted as nursing errors. The problem is thus social, socioeconomic, and independent of patient behavior: Shortage of nurses, time pressure, lack of health care funding [1]. In contrast, venous leg ulcers and DFS depend on the patient’s cooperation for their healing tendency.

The therapy of venous leg ulcers is standardized: Problems arise due to pain, which prevents adequate wound cleansing. In addition to deficiencies in compression bandaging techniques [2], the main problem is that patients rarely or never wear their compression stockings. For DFS, there is initially a widespread belief that there is an “occlusive microangiopathy” that is causative for poor wound healing. That this fantasized microangiopathy does not exist at all reflects an interesting epistemological problem of thinking style communities that cannot be further presented here. If macroangiopathy exists, it can be corrected today with impressive methods. The chronicity of DFS arises from diabetic polyneuropathy: the necessary pressure relief is not maintained because of polyneuropathy-induced anesthesia, patients walk around on their wounds and rarely or never wear the offloading devices.

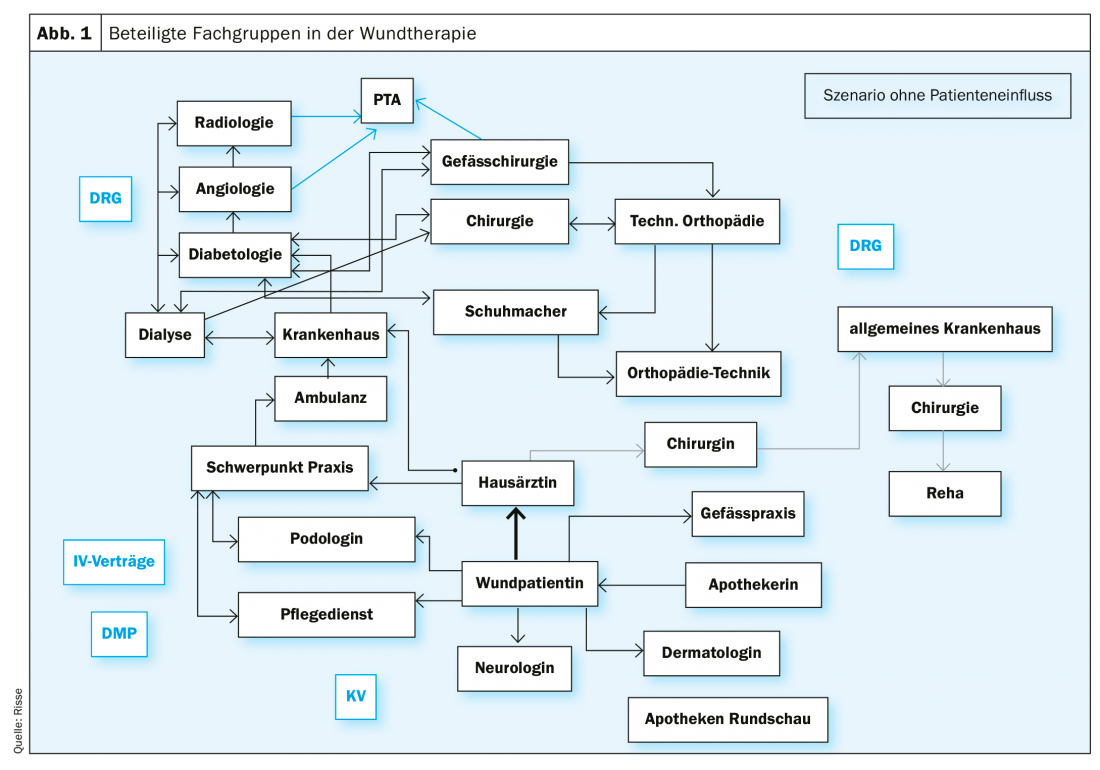

The organ medical strategies for all three conditions are well established and also widely published in evidence-based guidelines. However, the patient’s cooperation (so-called compliance, adherence) could not be improved. “Research efforts have focused on an increasing number of interventions to promote treatment adherence, with meta-analysis results indicating only moderate success” [3]. Beyond the problem areas of technology and patient cooperation, it is true for all three disease groups that successful therapy must be interdisciplinary, multiprofessional and transsectoral, ideally coordinated by the primary care physician [4,5]. The diagram provides an overview of the actors involved (Fig. 1).

In game-theoretical diction, there is a “cooperation of rational egoists” [6], a constellation that is doomed to failure without external control. There is no overarching coordination in chronic wound care. Objectively necessary things are thus subjectively accidental and dependent on the respective transference and countertransference relationships of the therapists involved. The problems therefore arise in the psychosocial context.

Compliance and non-compliance

“Compliance” refers to patients’ adherence to physician-prescribed behavioral measures. In most cases, such behavioral measures involve a more or less intensive change in the patient’s lifestyle. Attempts to get people to make lifestyle changes have proven largely unsuccessful. “Non-compliance” results in poor treatment outcomes. These lead to various reactions on the part of the therapist in a spectrum between frustration, helplessness and aggression (“unmotivated patient”). Another typical reaction is found towards the behavior of people with DFS: bewilderment or perplexity, due to the altered anthropological matrix in diabetic polyneuropathy (“body island atrophy”).

The term “non-compliance” is often negatively coded, implying the possibility of free will formation by the patient or the patient’s lack of will to behave in a way that is adequate for health, and thus refers to a philosophical problem complex that has not been discussed in much depth by organ medicine. Order clarification, assessment and patient status (DeShazer) should be clarified in advance to avoid disappointment or even therapy discontinuation.

An early study [7] of patients with chronic wounds found the following factors influencing so-called compliance:

- Extent of understanding of the measures of the therapists

- Patient’s understanding of the severity of their condition and their vulnerability

- Pain

- Extent of the necessary lifestyle changes

- Extent of the annoyance caused by the disease in contrast to the expected benefit from the therapeutic measures

- The complexity of the measures to be performed by the patient

Accordingly, the expert standard for the care of people with chronic wounds formulates the following principles [8]:

- Close cooperation with those affected, their relatives and the professional groups involved.

- Acute pattern care is not appropriate as it is not compatible with the chronic nature of the disease or the everyday needs of patients/residents.

- These experiences have a considerable impact on the cooperation of the persons concerned with the professional actors, but also on the type and extent of self-management. Patients/residents who are described as “non-compliant” with regard to compression therapy, for example, usually disregard the prescriptions not for reasons of poor comprehension or lack of willingness to cooperate, but because of divergent ideas about the therapy and its relevance.

- Studies on the topic of “chronic diseases” show that affected people do not always aim for optimal disease management in their care, but primarily for “normality” in everyday life.

- Appreciative communication and needs-based care planning, training and guidance for those affected are considered important prerequisites for the successful treatment of people with chronic wounds.

The therapists’ side: If the therapists suspect that the patient does not comply with the orders, the so-called “doctor-patient relationship” is often disturbed. The lack of success in therapy then leads to different rections depending on the character organization of the therapist, e.g.

- Frustration

- Resignation

- Aggression

- Cynicism

- Debasement

Difficulties with noncompliance arise when physicians misperceive themselves as “leaders” of patients. Therapists susceptible to this speak unquestioningly of “patient management” and of “my patient(s).” In such a semantic field, both excessive demands and disappointment are inevitable. The misunderstanding of necessary leadership by the physician is grounded in traditional medical training and socialization on acutely ill patients. Here the action of the physician is necessary and the success of the therapy depends on his qualification, knowledge and skill. The situation changes radically for chronically ill patients. “If it (scientific medicine) is central in acute diseases, it is only one, albeit indispensable, part of the therapeutic process in chronic diseases. It provides the basis of diagnostic and therapeutic tools and measures (…). In the long-term course of the disease, however, the quality of the treatment and thus the prognosis depends to a large extent on the patient and how he or she deals with the disease, i.e., how smoothly the necessary therapeutic measures are adapted to his or her daily life [9].

Order clarification and patient status

Therapies with chronically ill people fail when there is no agreement at the beginning about the strategies to be adopted together. Clarification of the order may initially be time-consuming, but in the further course it is helpful for all parties involved. The definition of the patient status (visitor, complainant, client) and the order clarification are indispensable prerequisites of a therapy process without the problems of non-compliance or even deception [10]. Sound order clarification is again dependent on the assessment of the patient under the question: What can the patient do? Here, the psychopathological influencing factors gain fundamental importance. The current epidemiological development with an increase in dementia in old age, partly accelerated by diabetes mellitus [11], applies to all patient groups.

For operationalizing diagnostics, appropriate diagnostic manuals are available [12], and a clinical introduction for organ therapists without prior psychiatric training can be found at [13]. Beyond the psychiatric diagnosis, the assessment also includes the psychomotor dimensions, e.g. the question whether the patient is able to see his feet at all, should he already be lasered, or the question to what extent the existing pain limits his ability to act [13].

An increasingly relevant problem area, so far little considered, is the adaptation of therapy strategies to the cultural background of the patients. Culturally determined body images, habitual corporeality, and religious and ethnic influences must be addressed and included in the planning. There is a considerable lack of knowledge here. An approach to the topic can be found in rudiments and cannot be further elaborated here [14,15].

The question of reasonable willfulness

“Non-compliance” is often the coding for the patient’s unwillingness to follow medical advice, medical orders. This connotation is particularly widespread in the area of nutritional recommendations and reduction diets, but is also found in the area of chronic wounds, e.g., towards patients who do not wear their compression stockings or, in the case of diabetic foot syndrome, do not comply with their pressure relief measures. In this context, moralizing contamination of the recommendations or even open accusations then regularly emerge.

The fundamental question of the possibility of free will has not been settled over centuries of philosophical discussion [16] and should therefore not be assumed lightly, as is often the case in medical discourse [17]. Obviously, freedom of will is completely withdrawn in patients with dementia, so that moral and moralizing aspects are missing in the problem of pressure sores. Likewise, freedom of will is obviously completely withdrawn in patients with psychiatric illnesses and significant social problems in their environment. The fact that stringent adherence fails to materialize in the case of underlying depressive disorders is apparent to almost all therapists. The assessment is already difficult in the case of so-called artifact patients [18], i.e. in people who – more or less – consciously maintain their chronic wounds. Here, too, we often find uncritical and devaluing remarks such as the misused term “Munchausen syndrome,” which reflects the therapist’s frustration and aggression rather than a rational, level-headed approach to the complex somatopsychic problem of noncompliance.

All in all, the problem complex described here refers to the anthropologically and ontologically fascinating area of “will and volition” [19] and thus fundamentally to the body-soul problem [20] and should also be discussed in this dimension among therapists on the occasion of each individual patient.

Chronic wounds in people with diabetes mellitus

While the above considerations apply to pressure sores, leg ulcers and chronic wounds of rare etiologies, the question of the psychosomatic relationship between patient behavior and the course of therapy in diabetes mellitus has changed completely. Diabetic polyneuropathy as the only necessary and at the same time sufficient condition for the occurrence and recurrence frequency of the lesions implies a radical change in the whole anthropological matrix of the patient, which is neither comprehensible nor explicable by the usual constellationist methods of psychology and the premise of anthropological dualism. Due to the neuropathically caused “body island atrophy” [21] the feet become so-called “environmental components” from which subjectivity is withdrawn. While the therapists encounter the patient and the wound on the level of the body machine, the patient acts on the level of subjective factuality [22].

This leads to three phenomena:

- The patient goes to the doctor too late

- The primary treating physician underestimates the severity of the disease due to lack of symptoms

- Some of the lesions leading to hospitalization are grotesque:

Communication problems are consequently obligatory. Like the polyneuropathy syndrome of leprosy or syphilis, patients lack reflexive protective mechanisms, making injury inevitable even when cognitive capacity is intact. The categorical importance of polyneuropathy and the constant “body island atrophy” caused by it is overlooked in almost all medical thinking styles.

A first approximation to the overlooked subject is given by the authors of the seminal monograph on DFS, Hochlenert, Engels, Morbach [23]: “The central feature of diabetic foot syndrome is the reduced pain development in initial damage. This is also called “loss of protective sensation” and is a consequence of the loss of fine nerve fibers. Normal avoidance behavior and calling for help therefore do not occur to the appropriate extent, and extended damage can occur. The extent of heedlessness displayed by those affected is astounding to those inexperienced in dealing with people with reduced sensation.”

Both disorders together, body island atrophy and lack of protective reflexes, automatically lead to involuntary patient behavior with frequent recurrences and permanent pressure overload of the wounds. Therapists who are close to the body, such as wound managers, podiatrists or nurses, are more familiar with these behaviors than medical therapists who are distant from the body. The term “compliance” as a measure of the patient’s ability to follow medical orders is therefore inappropriate in this context because it is meaningless. The problem context described in this condensed form, which seems abstract and is difficult to comprehend at first approximation, has been presented in more detail in many places [24]. He can help to improve or even relax the disturbed doctor-patient relationship by understanding the bodily basis.

Possible solutions [25]

- As with all chronic diseases and their therapy, the “clarification of the order” is at the beginning (and is categorically missed in realiter).

- Systematic assessment should precede wound therapy.

- The patient’s biographical context and character organization should be accepted as limiting organic therapies.

- Brain-organic psychosyndrome as one of the most common accompanying disorders should be able to be diagnosed by psychopathological competence.

- The therapeutic setting would also have to include the possibility of open communication in the therapy of chronic wounds.

- Open communication also means providing patients with in-depth information about the therapy and making the meaning of behavioral changes transparent to them. However, the problem of lacking transparency seems to become more and more significant in times of increasing acceleration of processes and strongly shortened waiting times.

- Countertransference effects of the therapist such as frustration, resignation, or aggression are signs of the therapist’s own excessive demands, either due to excessive expectations of the patient, an inadequate concept of illness, or a distorted anthropological construct. Self-reflection should therefore be placed before blaming the patient with terms such as “non-compliance”.

- Lastly, the pursuit of treatment adherence also and essentially demands compliance and adherence of therapists to established therapies. Even this banal prerequisite does not always seem to be given.

For patients with DFS

- Radical change of the bodily economy and thus of the totality of man and his life-world: “loss of perception” is not a loss of perception of the body by a psyche. This is a radical change of the bodily economy and thus of the totality of man and his life world caused by “body island shrinkage”.

- Signaling understanding by the therapists: Patients with body island at rophy due to diabetogenic polyneuropathy suffer even without prominent symptoms. They can no longer “stand with both feet in life”. Therapists should always signal understanding here, and if necessary also ask about existing suicidal thoughts.

- If signs of polyneuropathy are detected during the examination, the patient should be asked to describe what he feels “around” his feet. For examples of such sensations and suffering through insensibility, see Risse [24].

Healthy therapists

Healthy therapists are optimally prepared for acute emergencies/interventional measures without fantasies of omnipotence through ongoing education and training. This also applies to the organization and team interaction of the treatment unit.

Healthy therapists who counsel and care for people with chronic diseases respect the patient’s personal life plan and can also be satisfied with medically suboptimal solutions. The inner attitude here refers to the quality of the knowledge that is imparted as a quality standard and measure of self-assessment. Consequently, healthy therapists cannot speak of “patient management.” The conversation between the healthy therapist and the patient, together with a qualified assessment (What can the patient do?), leads first to clarification of the order [13], and then to problem solutions in the individual context. “Poor compliance” or an “unmotivated patient” can therefore not occur as a problem at all under these circumstances.

Healthy patients and their healthy therapists

Known for decades, but not noticed in organ medicine including diabetology, are the results of family therapy research and systemic counseling. At the end of a treatment, patients are then not satisfied with their doctor if it was not clarified at the beginning what is to be worked on. This means that at the beginning of a treatment of chronic diseases there is always the order clarification, a technique that is easy to learn and has already been worked on and published in detail for diabetological questions [13]. The same strategies apply to order clarification in the treatment of chronic wounds.

In the setting of chronic wounds, three concise types of patient status can be distinguished:

- The customer has a problem (high BG values) and clear ideas of a solution (wound management, certified institution, etc.).

- The complainant has a problem (painful wound, fever, odor) but no solution.

- The visitor does not have a problem (polyneuropathy, body island atrophy) and therefore does not request help.

The visitor is now the one who causes great problems for the organ therapist. The technical possibilities have also been known for a long time, unfortunately also not taken note of. A first hint with encouragement for further reading: If the patient has no complaint, then De Shazer suggests “that the therapist merely compliments. […] Since there is no complaint to be treated, therapy cannot begin […] and it would therefore be a mistake for the therapist to try to intervene, even if the ‘problem’ is is obvious to an observer” [10].

Take-Home Messages

- The treatment of chronic wounds is fundamentally interdisciplinary, multiprofessional and transsectoral: cooperation of rational egoists.

- The treatment of chronic wounds always requires the patient’s consent.

- The term “compliance” should not be used in the management of chronic wounds.

- Diabetic polyneuropathy means “body island atrophy” in an anthropological perspective.

- The behavior of patients with DFS therefore often evokes perplexity or even aggression for the inexperienced.

Literature:

- Risse A: Limitations and deficiencies: what are the limitations of chronic wound care? Social Policy Commentaries 2016; 57, special issue no. 2: 22-24.

- Protz K, Timm JH: Modern wound care; 9th edition, Urban & Fischer 2019.

- Petrak F, Meier JJ, Albus C, et al: Motivation and diabetes – Time for a paradigm shift? A position paper. Diabetology and Metabolism 2019; 14(03): 193-203.

- Storck M, Dissemond J, Gerber V, Augustin M: Expert council structural development wound management: competence levels in wound care. Recommendations for improving the care structure for people with chronic wounds in Germany. Vascular Surgery 2019; 24: 388-398.

- Risse A: The diabetic foot syndrome – an interdisciplinary problem. Hemostaseology 2007; 2: 1-6.

- Raub W. The social structure of cooperation among rational egoists. Z.f.Sociology 1986; 5: 309-323.

- Morrison M, Moffartt C, Bridel-Nixon J, Bale S: Nursing Management of Chronic Wounds. London, Philadelphia, Mosby 1997; 140-141.

- German Network for Quality Development in Nursing (DNQP (ed.): Expertenstandard Pflege von Menschen mit chronischen Wunden. Osnabrück, self-published 2008; 9.

- Burger W: The contribution of New Phenomenology to the understanding of chronic illness. Rostock Phenomenological Manuscripts. Grossheim M (ed.) Rostock 2012.

- De Shazer S: The twist. Surprising Twists and Solutions in Brief Therapy, 4th ed. Heidelberg, C. Auer 1995.

- Fatke B, Förstl H: Diabetes mellitus and dementia. The Diabetologist 2013; 3: 1-8.

- Saß H, Wittchen HU, Zaudig M, Houben I: Diagnostic criteria – DSM-IV-TR, Göttingen, Hochgrefe 2003.

- Siebolds M, Risse A: Epistemological and systemic aspects in modern diabetology, Berlin, New York 2002; 36-37; 119-125.

- Kalvelage B, Kofahl C: Treatment of migrants with diabetes. In F. Petrak, & S. Herpertz (Eds.), Psychodiabetology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer 2013; 73-91.

- Gillessen A, Golsabahi-Broclawski S, Biakowski A, Broclawski A (eds.): Intercultural communication in medicine; Springer 2020; in press.

- Keil G: Freedom of the Will. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter 2007; Schmitz H: Freiheit. Freiburg, Munich, Karl Alber 2007.

- Foerster K, Dreißing H: The “reasonable effort of will” in socio-medical assessment. Neurologist. 2010; 81: 1092-1096.

- Rehbein J: Physician – Patients – Communication. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter 1993; 136-146.

- Janzarik W: Want and Will. Neurologist 2008; 79: 567-570.

- Brüntrup G: The Body-Soul Problem. 3rd ed. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer 2008.

- Schmitz H: System der Philosophie Vol. 2,1. The body. Bonn, Bouvier 1965, 165-167.

- Schmitz H: New Foundations of Epistemology. Bonn, Bouvier 1994, 59-60 u. 168.

- Hochlenert D, Engels G, Morbach S: The diabetic foot syndrome; Springer 2014; 7.

- Risse A: Anthropological significance of polyneuropathies for patients and care. Qualitative, neo-phenomenological contribution. The Diabetologist 2006; 125-131.

- Hasenbein U, Wallesch CW, Räbiger J: Physician compliance with guidelines. An overview in light of the introduction of disease management programs. Gesundh ökon Qual manag. 2003; 8: 363-375.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(2): 8-13