Since the introduction of triptans in the 1990s, there have been few innovations in the development of migraine therapy. Currently, however, a number of promising substances or neurostimulation methods are in advanced phases of clinical testing – both for acute therapy of migraine and for prophylaxis.

Migraine is a neurological disorder with stereotypically recurrent attacks of moderate to severe, often pulsating headache, sensitivity to light, noise, and smell, and nausea. The pain usually intensifies with physical activity [1]. In the WHO Global Burden of Disease Survey 2010, migraine is listed as the third most common human disease. Migraine has been found to cause more than 50% of “years lived with disability” due to neurological conditions.

In the 1990s, important new treatment options for acute migraine became available in the form of triptans, which now have a permanent place in treatment algorithms. Since then, there have been few innovations in both acute therapy and prophylaxis, despite considerable research efforts. Fortunately, the tide now seems to be turning again, especially with regard to prophylaxis: A number of promising substances or neurostimulation methods have either already been successfully tested or are currently in advanced phases of clinical trials. A selection of current study results on pharmacological and interventional therapy options will be discussed separately for acute therapy and prophylaxis of migraine in the following. Non-drug (e.g., psychological) methods are not discussed in this article, but they are also highly valued.

Acute therapy of migraine

For severe migraine attacks, triptans such as sumatriptan 50 mg in tablet form are usually the treatment of choice. However, oral application is sometimes opposed by migraine-associated nausea and vomiting. In these cases, sumatriptan or zolmitriptan nasal spray, sumatriptan suppositories or rizatriptan or zolmitriptan melting tablets may be considered; in particularly severe attacks, sumatriptan 6 mg subcutaneously may also be used.

In 2013, the FDA approved another therapeutic option for such cases in the form of an iontophoretic transdermal system, but this has not yet been approved by Swissmedic. In this system, sumatriptan is absorbed transdermally by a weak electric current, bypassing the gastrointestinal tract. There was clear evidence of efficacy compared with placebo, but it appears to be somewhat weaker than with some oral triptans.

Patients presenting to the emergency department with severe migraine attacks present a special challenge because severe migraine attacks respond worse to medication and these patients have usually already been taking oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or triptans. Therefore, parenteral substances are particularly suitable for such patients. A recent double-blind study of 330 patients compared intravenous administrations of valproate (1000 mg), metoclopramide (10 mg), or ketorolac (30 mg). Here, valproate performed worse than metoclopramide and ketorolac with respect to primary and secondary efficacy parameters. Surprisingly, metoclopramide was more effective than the nonsteroidal analgesic ketorolac [2].

A meta-analysis (five randomized-controlled trials) was dedicated to the study situation of intravenous magnesium for migraine acute therapy [3]. No positive effect of magnesium was found in terms of pain reduction and rescue medication use, and magnesium-treated patients complained more often of side effects. In this respect, magnesium for acute therapy cannot be considered a useful therapeutic option, in contrast to magnesium for migraine prophylaxis.

Also of interest is a case series on the use of beta-blockers in the form of eye drops for acute migraine therapy. The described seven patients responded at least partially to the administration of appropriate eye drops (mostly timolol 0.5%). The authors argued that topical ocular administration can achieve relatively rapid effective plasma levels and therefore beta-blockers may also be suitable for acute therapy. However, this interesting observation has yet to be validated in prospective clinical trials.

Another interesting therapeutic approach uses peripheral nerve stimulation for acute, and in some cases prophylactic, migraine therapy. Different devices and stimulation sites have been investigated so far, but each in predominantly rather small and partly only uncontrolled studies. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (Gamma-Core® device) resulted in a rate of pain-free patients of 21% after two hours in an open study [4]. This rate is about the same as the response rate for the aforementioned transdermal sumatript indication. Further Sham-controlled studies are planned. One advantage of noninvasive neurostimulation procedures would certainly be that they could be combined with acute drug therapy without any problems.

Migraine prophylaxis

Classic migraine prophylactics include antiepileptic drugs (especially topiramate and valproate), calcium antagonists (flunarizine), beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol), and, as a second choice, antidepressants (e.g., tricyclics). Taking prophylactic medications can be expected to reduce attack frequency by about 50% in about one in two patients. Side effects of the aforementioned substances (including weight gain, fatigue, cognitive side effects, nausea, etc.) are a major problem in migraine prophylaxis, so more options are desirable.

For several decades, the neuropeptide “Calcitonin Gene-related Peptide” (CGRP) has been thought to play an important role in migraine pathophysiology. Thus, elevated levels of CGRP have been demonstrated in migraine attacks [5], and CGRP infusions have been shown to trigger migraine attacks. Furthermore, CGRP receptor antagonists were effective in Mi-gräne acute therapy and prophylaxis [6,7]. However, transaminase elevations occurred, particularly in the latter prophage study, which probably represent a class effect that also applies to other CGRP receptor antagonists (so-called Gepants). Further clinical development of these substances has therefore been halted for the time being.

However, the basic mode of action has now been revisited with CGRP antibodies. These are monoclonal antibodies directly against CGRP. Antibodies against the CGRP receptor are also currently being tested. Recently, the results of the first phase II trials of prophylaxis of episodic migraine (<15 headache days per month) with CGRP antibodies were published [8,9]. The two humanized CGRP antibodies ALD403 (single i.v. administration of 1000 mg) and LY2951742 (subcutaneously every two weeks for 12 weeks) showed better efficacy than placebo in reducing the number of migraine days with good tolerability. These and other compounds are expected to enter Phase III clinical trials shortly. Swiss centers are also likely to participate in these studies. It remains to be seen to what extent the parenteral form of administration of the antibodies will be accepted by migraine patients. Fortunately, the intervals between applications are quite long (at least two weeks). The advantage of these substances could be the fact that, according to current knowledge, they do not lead to weight gain (e.g., valproate and flunarizine) and fatigue (e.g., beta-blockers, flunarizine, tricyclics) as do many established migraine prophylactics.

For agents already approved, there is evidence that the angiotensin II receptor blocker candesartan is effective in migraine prophylaxis. This had been suggested by an earlier smaller, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study with candesartan (16 mg orally) and 60 patients [10]. The same authors have now tested candesartan 16 mg in a new cross-over study against the established migraine prophylactic propranolol (160 mg daily) and placebo. Candesartan showed a similar effect size to propranolol in reducing migraine and headache days. Both agents were superior to placebo. A previous study (n=95) of episodic migraine prophylaxis with telmisartan 80 mg had remained negative, at least with respect to the primary end point [11], so candesartan may have specific effects and may offer itself as a relatively low side-effect (off-label) alternative to current migraine prophylactics.

Hormonal factors play an important role in migraine. This is underscored by the frequent triggering of migraine attacks by menstruation and the fact that women are affected by migraine more frequently than men only between menarche and menopause – in childhood and old age, migraine occurs with about equal frequency in both sexes. Furthermore, patients suffering from migraine with aura and using estrogen-containing contraceptives are at increased risk for cerebrovascular events. A first small, open-label study (n=37) from Zurich has shown evidence of positive effects of progestin-only contraception (desogestrel) on migraine frequency and quality of life [12]. Prospective studies on this topic are planned.

For the treatment of chronic migraine (≥15 days per month with headache, of which at least seven are migraine-typical), botulinum toxin A has been approved in the EU, but not by Swissmedic. In principle, botulinum toxin therapy for migraine is therefore only possible off-label in Switzerland. In the past, various studies with botulinum toxin for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine and tension headache had remained negative, but two large placebo-controlled studies on chronic migraine had shown an effect of botulinum toxin A. Interesting are new findings by Burstein et al. who could show in animal experiments that extracranial botulinum toxin injections can inhibit specific branches of meningeal nociceptors [13]. Thus, there is at least some pathophysiologic plausibility of botulinum toxin injections in chronic migraine.

Previous observational studies showed a positive effect of invasive vagus nerve stimulators implanted in patients with refractory epilepsy on their comorbid migraine frequency. The aforementioned noninvasive vagus nerve stimulator is therefore also being investigated for migraine prophylaxis. Initial results in chronic migraine show good tolerability with daily application, but only a modest reduction in attack frequency.

Already investigated by means of a multicenter, randomized, Sham-controlled trial, non-invasive supraorbital neurostimulation (Cefaly® device) [14]. 67 patients with episodic migraine were stimulated daily for 20 minutes over three months. The 50% responder rate was significantly higher in the verum-treated group (38.1%) than in the Sham-stimulated patients (12.1%).

Conclusion for practice

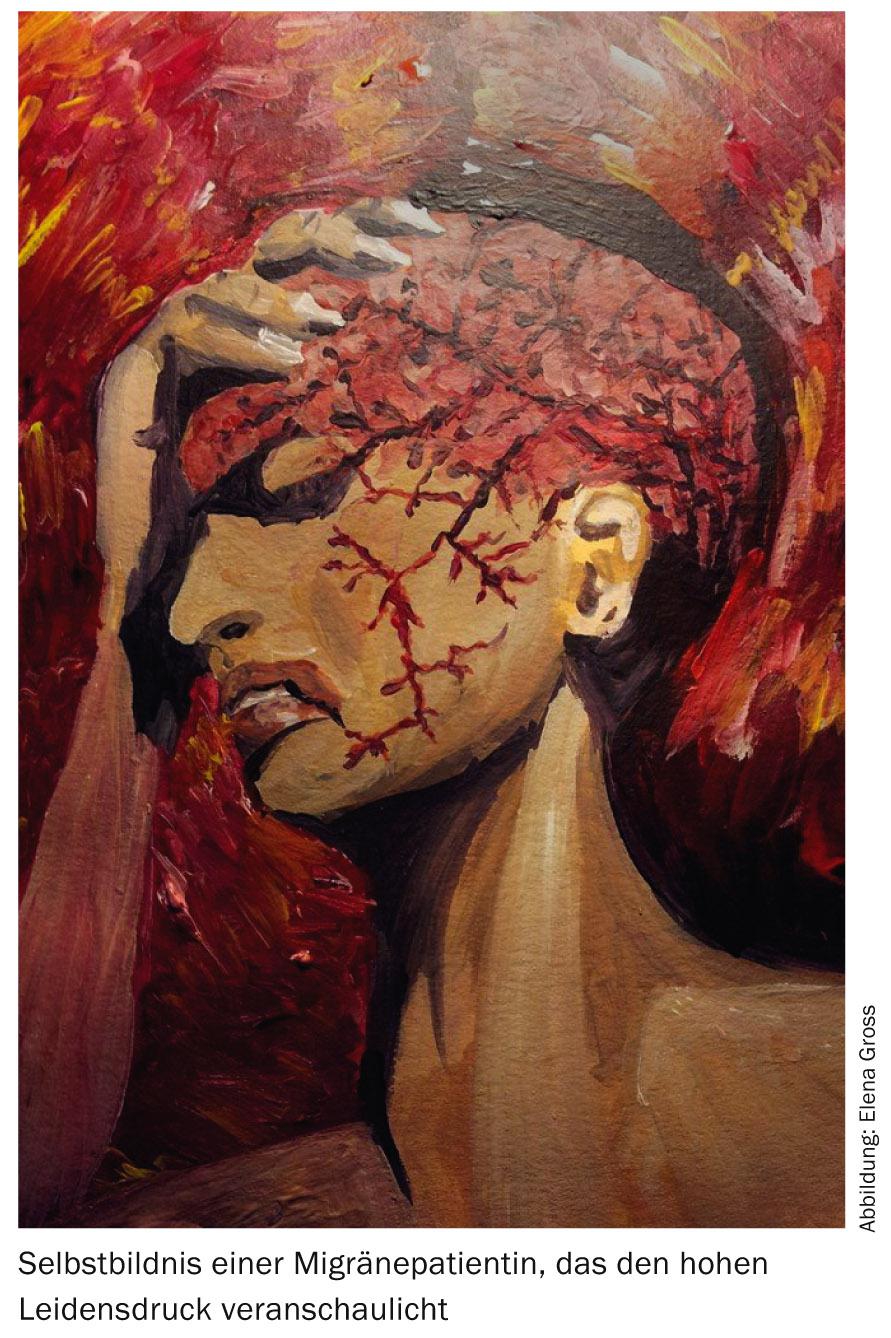

- Migraine is a common and treatable condition that can lead to a high level of distress.

- In the field of acute therapy, new routes of application of known substances will in future be

- (e.g. sumatriptan patch) and possibly neurostimulation procedures (e.g. Gamma-Core® device) are available.

- Non-invasive nerve stimulation procedures could also play a role in the future in the context of migraine prophylaxis.

- Candesartan may be considered as a drug alternative to established migraine prophylactics, but is not approved for this indication.

- CGRP antibodies intervene directly in the pathophysiological process in migraine, are currently in clinical trials and could enable a completely new therapeutic principle for migraine prophylaxis.

Prof. Dr. med. Till Sprenger

MSc Elena Gross

Literature:

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 Suppl 1: 9-160.

- Friedman BW, et al: Randomized trial of IV valproate vs metoclopramide vs ketorolac for acute migraine. Neurology 2014; 82(11): 976-983.

- Choi H, Parmar N: The use of intravenous magnesium sulphate for acute migraine: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European journal of emergency medicine: official journal of the European Society for Emergency Medicine 2014; 21(1): 2-9.

- Goadsby PJ, et al: Effect of noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation on acute migraine: an open-label pilot study. Cephalalgia 2014; 34(12): 986-993.

- Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L, Ekman R: Vasoactive peptide release in the extracerebral circulation of humans during migraine headache. Ann Neurol 1990; 28(2): 183-187.

- Ho TW, et al: Efficacy and tolerability of MK-0974 (telcagepant), a new oral antagonist of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor, compared with zolmitriptan for acute migraine: a randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet 2008; 372: 2115-2123.

- Ho TW, et al: Randomized controlled trial of the CGRP receptor antagonist telcagepant for migraine prevention. Neurology 2014; 83(11): 958-966.

- Dodick DW, et al: Safety and efficacy of ALD403, an antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of frequent episodic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, exploratory phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13(11): 1100-1107.

- Dodick DW, et al: Safety and efficacy of LY2951742, a monoclonal antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of migraine: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13(9): 885-892.

- Tronvik E, et al: Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 289(1): 65-69.

- Diener HC, et al: Telmisartan in migraine prophylaxis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Cephalalgia 2009; 29(9): 921-927.

- Merki-Feld GS, et al: Desogestrel-only contraception may reduce headache frequency and improve quality of life in women suffering from migraine. J European Society of Contraception 2013; 18(5): 394-400.

- Burstein R, et al: Selective inhibition of meningeal nociceptors by botulinum neurotoxin type A: therapeutic implications for migraine and other pains. Cephalalgia 2014; 34(11): 853-869.

- Schoenen J, et al: Migraine prevention with a supraorbital transcutaneous stimulator: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology 2013; 80(8): 697-704.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(1): 10-13