The treatment arsenal for chronic urticaria includes several 2nd generation antihistamines – still the treatment of first choice – the monoclonal antibody Omalizumab and the immunosuppressant Ciclosporin A as an add-on. There are interesting new findings from various studies with regard to dosage regimes and prediction of treatment response. There is much to be said for an individualized approach within the framework of the scheme recommended by the guideline.

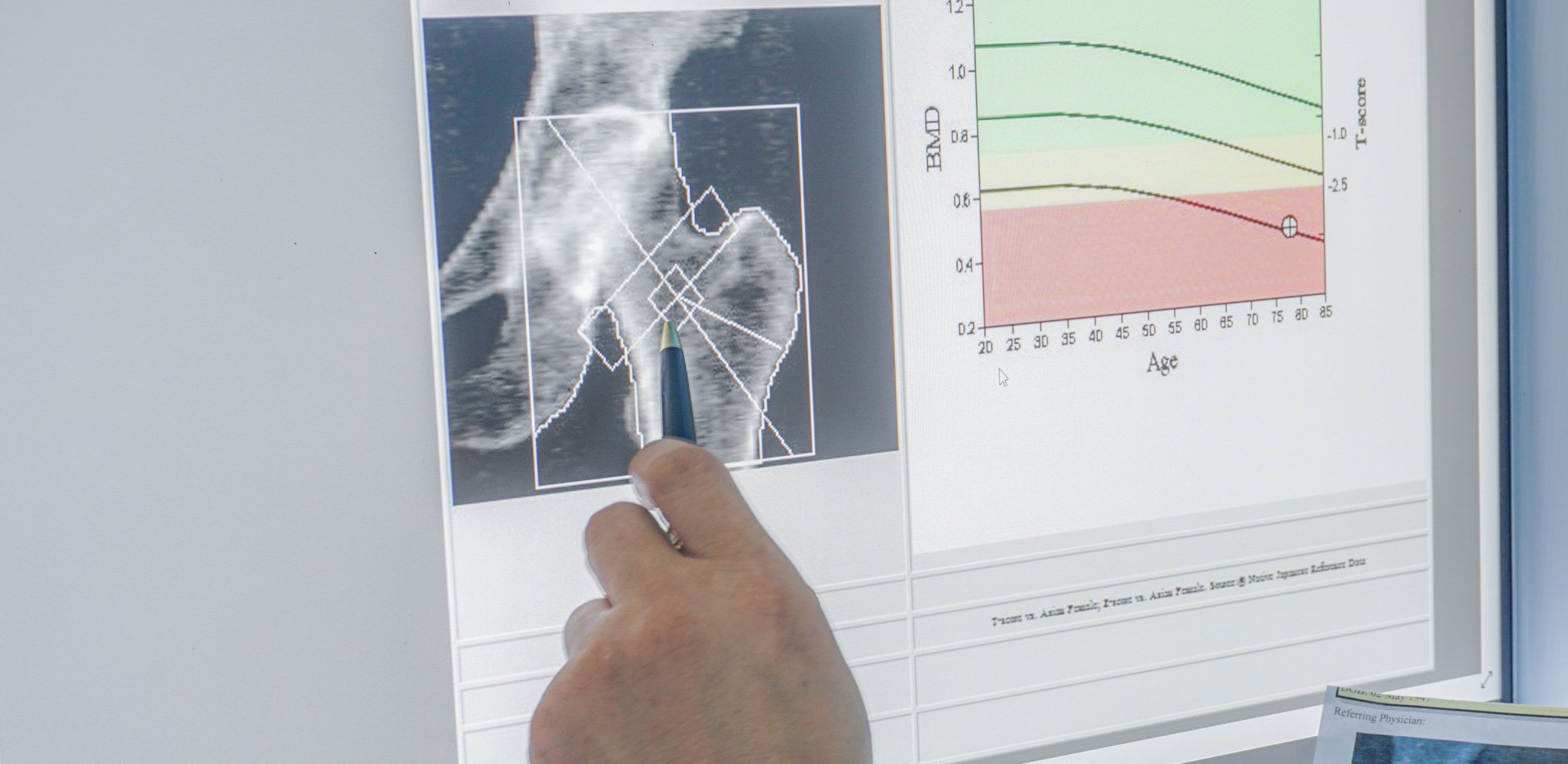

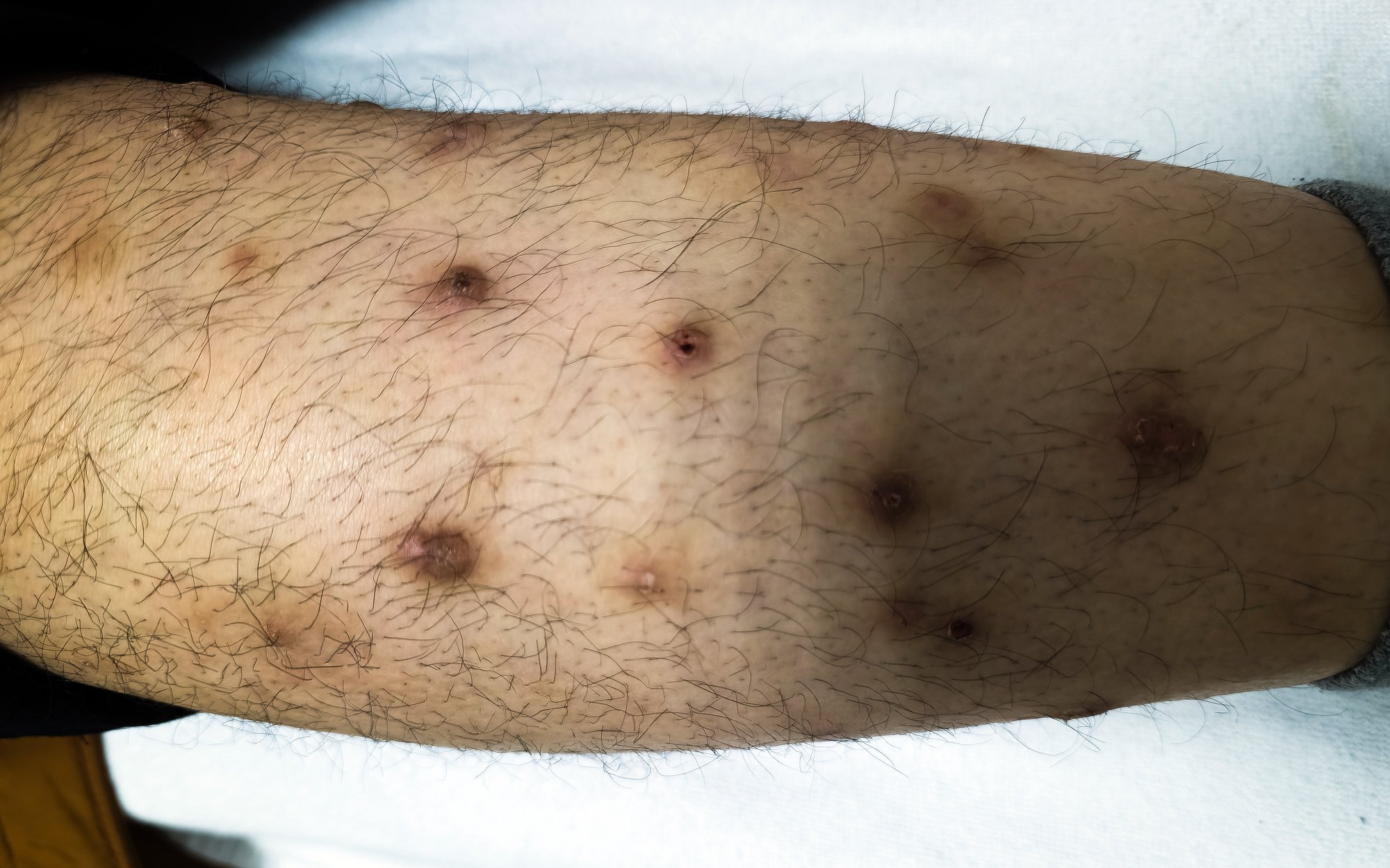

Urticaria is a distressing disease triggered by mast cells, characterized by wheals and/or angioedema, accompanied by severe itching. Chronic urticaria is when the symptoms persist for more than six weeks. A distinction is made between chronic spontaneous and chronic inducible urticaria (CSU or CindU). The latter is triggered by certain factors such as heat, cold, light, pressure, mechanical irritation or an increase in core body temperature. In terms of a “treat-to-target” approach, a multi-stage treatment strategy is used to achieve complete freedom from symptoms in chronic urticaria (CU) (Fig. 1). “Our goal is to achieve complete remission of symptoms and signs as quickly as possible, i.e. no wheals, no angioedema and no itching,” explained Prof. Ana M. Giménez-Arnau, MD, PhD, Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona [1]. For example, the Weekly Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7)$ and the Urticaria Control Test (UCT)& are available for routine clinical practice to determine CU disease activity and response to treatment.

$ UAS7=sum score of seven consecutive days; complete control and normalization of quality of life is achieved when the UAS7 is 0.

& UCT=simple four-item instrument with a clearly defined threshold for “well-controlled” vs. “poorly controlled” disease; the retrospective recording period or reminder period is four weeks.

Are there predictors for lack of response to antihistamines?

As first-line therapy for all forms of urticaria, an H1 antihistamine of the 2nd generation (H1-AH-2G) is recommended. Studies support the use of the H1-AH-2G bilastine, cetirizine, desloratadine, ebastine (maximum 40 mg/day), fexofenadine, levocetirizine and rupatadine in up to four standard doses (off-label) [2]. The simultaneous use of different H1 antihistamines is not recommended, and antihistamines of the 1st generation can no longer be used, explained Prof. Giménez-Arnau. The current guidelines also expressly advise against this – on the one hand, antihistamines of the 2nd generation are more effective and, on the other hand, the H1 antihistamines of the 1st generation (H1-AH-1G) has anticholinergic and sedative effects as well as a considerable interaction potential.

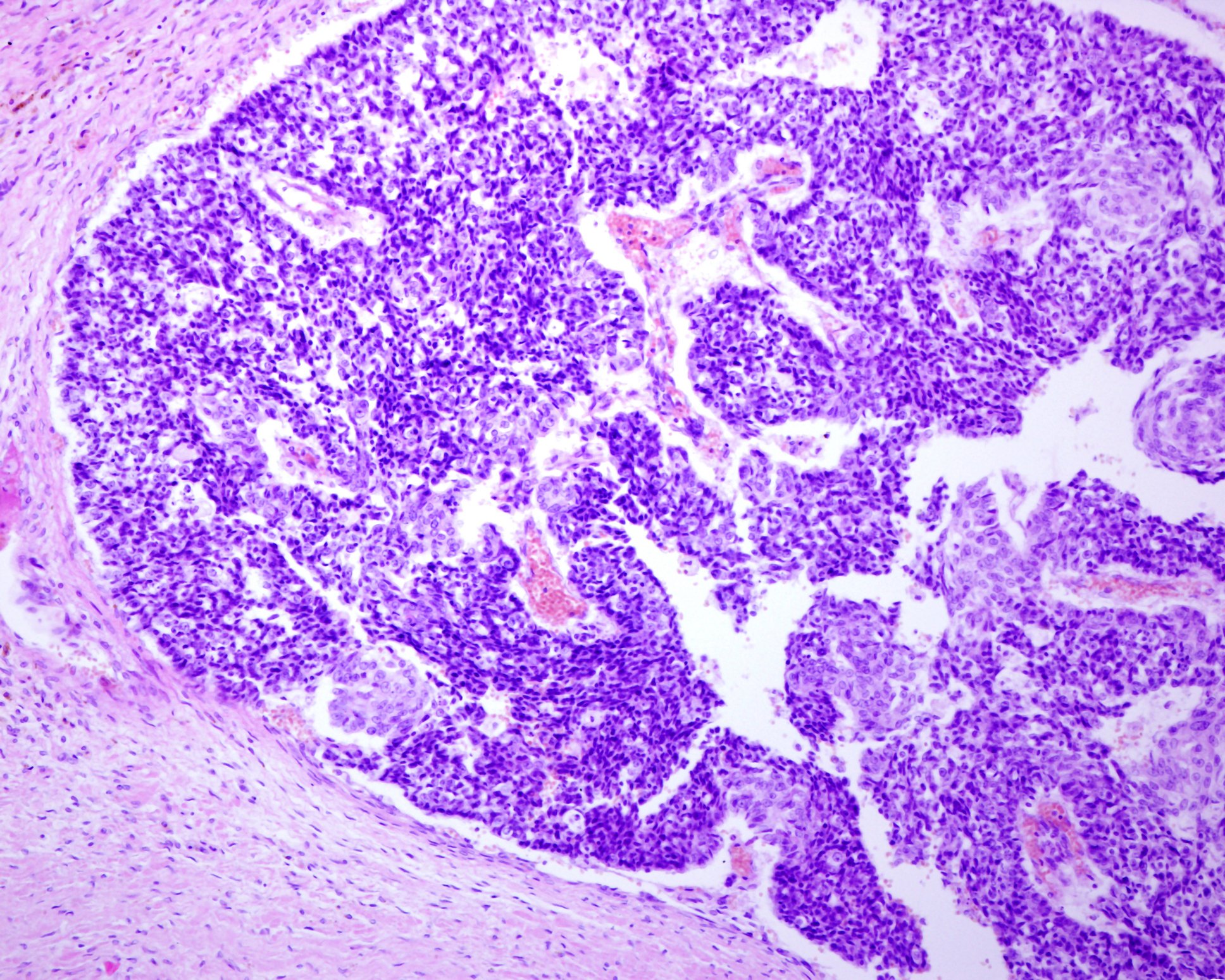

The AWARE study shows that the lower the values in the Urticaria Control Test (UCT), the higher the probability of a lack of treatment response to H1-AH-2G [3]. Another parameter with a negative predictive power with regard to treatment response is the D-dimer value [4]. It is known that CSU disease activity correlates positively with D-dimers. In addition, the skin of CSU patients with active disease has been shown to have immunological involvement and a peculiar genetic profile. A transcriptome analysis published in the journal Allergy shows that both non-lesional and lesional skin of CSU patients is characterized by overexpression of platelet-activating factor, which is particularly high in inflammatory infiltrates of lesional skin [5].

| Predictors for relapse after interruption of omalizumab therapy The question of how to predict symptom recurrence when omalizumab therapy is stopped after six months is addressed in a secondary analysis published in JACI in 2018. Analyses based on pooled data from the ASTERIA I and II studies indicate that a high baseline UAS7 score and a low UAS7 area above the curve (AAC)** are associated with a higher likelihood of rapid relapse of urticaria symptoms compared to low UAS7 and high AAC scores. |

| ** The AAC is determined by cumulating the UAS7 scores over different time points |

| to [11] |

Second-line therapy: increase the dose of omalizumab if there is a lack of response

If there is no improvement after 2-4 weeks of treatment with an H1-AH-G2 at up to four times the usual dose, the use of the biologic omalizumab as an add-on can be considered [2]. Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against immunoglobulin E (IgE). The antibody intercepts soluble IgE antibodies in the blood and interstitium before they bind to the mast cells and induce their degranulation and histamine release [12]. Although chronic urticaria is not an allergy, the IgE levels are often greatly increased. Analyses showed that patients with a lack of response to omalizumab therapy (non-responders) had much lower IgE levels (approx. 20 kU/l) and significantly lower FcεRI levels (box) compared to responders at baseline [6]. FcεRI expression of basophils at baseline has been suggested as a possible predictor of omalizumab response [6]. However, studies show that around a third of CU patients treated with omalizumab 150 mg or 300 mg remain symptomatic after 6 months of treatment. Whether it makes sense to continue treatment with a higher dosage of the antibody should be decided on an individual basis. Prof. Giménez-Arnau points out that in patients with a baseline IgE of around 40 kU/l, a therapy trial with omalizumab – possibly in an increased dosage – should definitely be considered [7].

| High affinity IgE receptor (FcεR1) IgE-mediated degranulation of mast cells begins with the activation of FcεR1 by IgE. Overexpression of FcεR1 associated with CU is not modified by treatment with H1-AH-2G, even if patients respond to antihistamine treatment. Treatment with the monoclonal antibody omalizumab, which is directed against IgE, may therefore be necessary to bring the disease under control. The effects of omalizumab are based on selective binding to IgE antibodies. The drug is injected subcutaneously every two to four weeks. |

| according to [1] |

In a multicenter Spanish observational study, 80% of those who showed a partial or no response to omalizumab 300 mg (every four weeks) continued treatment at a dose of 450 mg (every four weeks) and then increased to 600 mg (every four weeks). It was shown that 75% of those affected then achieved a UAS7 ≤6 and disease control [8]. Omalizumab has a very favorable safety profile, the speaker emphasized. Pregnant women as well as children and patients with comorbidities can be treated with this antibody.

Consider CsA as an add-on in the absence of a treatment response

For some CU patients who continue to suffer from symptoms despite receiving high-dose omalizumab therapy, a combination with low-dose ciclosporin A (CsA) should be considered. This applies in particular to those patients with a positive basophil test and low IgE serum levels [9]. If there is a partial response to omalizumab, it is suggested to add ciclosporin A at a dose of 1-3 mg/kg as an add-on; if necessary, the dose can be increased to 5 mg/kg [9]. CsA prevents T-lymphocyte activation, antibody formation and the release of mast cell mediators. In a meta-analysis, 70% of CSU patients treated with CsA at a dose of 2-4 mg/kg/d over a period of 12 weeks achieved an improvement in clinical severity [10].

Literature:

- «Therapeutic Strategy in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria, how to predict success?», Prof. Ana M. Giménez-Arnau, MD, PhD, EEACI Annual Meeting, 9–11 June.

- Zuberbier T, et al.: S3-Leitlinie Urtikaria. Teil 2: Therapie der Urtikaria – deutschsprachige Adaption der internationalen S3-Leitlinie. JDDG 2023; 21(Issue2): 202–216.

- Maurer M, et al.: Antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria: 1-year data from the AWARE study. Clin Exp Allergy 2019; 49(5): 655–662.

- Asero R: D-dimer: a biomarker for antihistamine-resistant chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132(4): 983–986.

- Gimenez-Arnau A, et al.: Transcriptome analysis of severely active chronic spontaneous urticaria shows an overall immunological involvement. Allergy 2017; 72(11): 1778–1790.

- Deza G, et al.: Basophil FcεRI Expression in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Potential Immunological Predictor of Response to Omalizumab Therapy. Acta Derm Venereol 2017; 97(6): 698–704.

- Ertas R, et al.: The clinical response to omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients is linked to and predicted by IgE levels and their change. Allergy 2018; 73(3): 705–712.

- Curto-Barredo L, et al.: Omalizumab updosing allows disease activity control in patients with refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria. Br J Dermatol 2018; 179: 210–212.

- Türk M, et al.: Experience-based advice on stepping up and stepping down the therapeutic management of chronic spontaneous urticaria: Where is the guidance? Allergy 2022; 77(5): 1626–1630.

- Kulthanan K: Cyclosporine for Chronic spontaneous urticaria. A meta-analysis and systematic review. JACI Pract 2018; 6: 586–599.

- Ferrer M, et al.: Predicting Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria Symptom Return After Omalizumab Treatment Discontinuation: Exploratory Analysis. JACI Pract 2018; 6(4): 1191–1197.e5.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2023; 33(5): 44–45