Cutaneous lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of neoplastic diseases arising from clonal proliferation of lymphocytes in the skin. Overall, cutaneous lymphomas are rare skin cancers, with a prevalence of 1:100,000 population. Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Early stages of MF are mainly treated topically with corticosteroids, phototherapy, or local radiation therapies. A unified WHO classification of primary cutaneous lymphomas (EORTC/WHO-based) has been in place since 2008. A distinction is made between T- and B-cell lymphomas, which is also clinically and therapeutically relevant. Cutaneous lymphomas have a completely different prognosis and therapy than the histologically comparable nodal lymphomas.

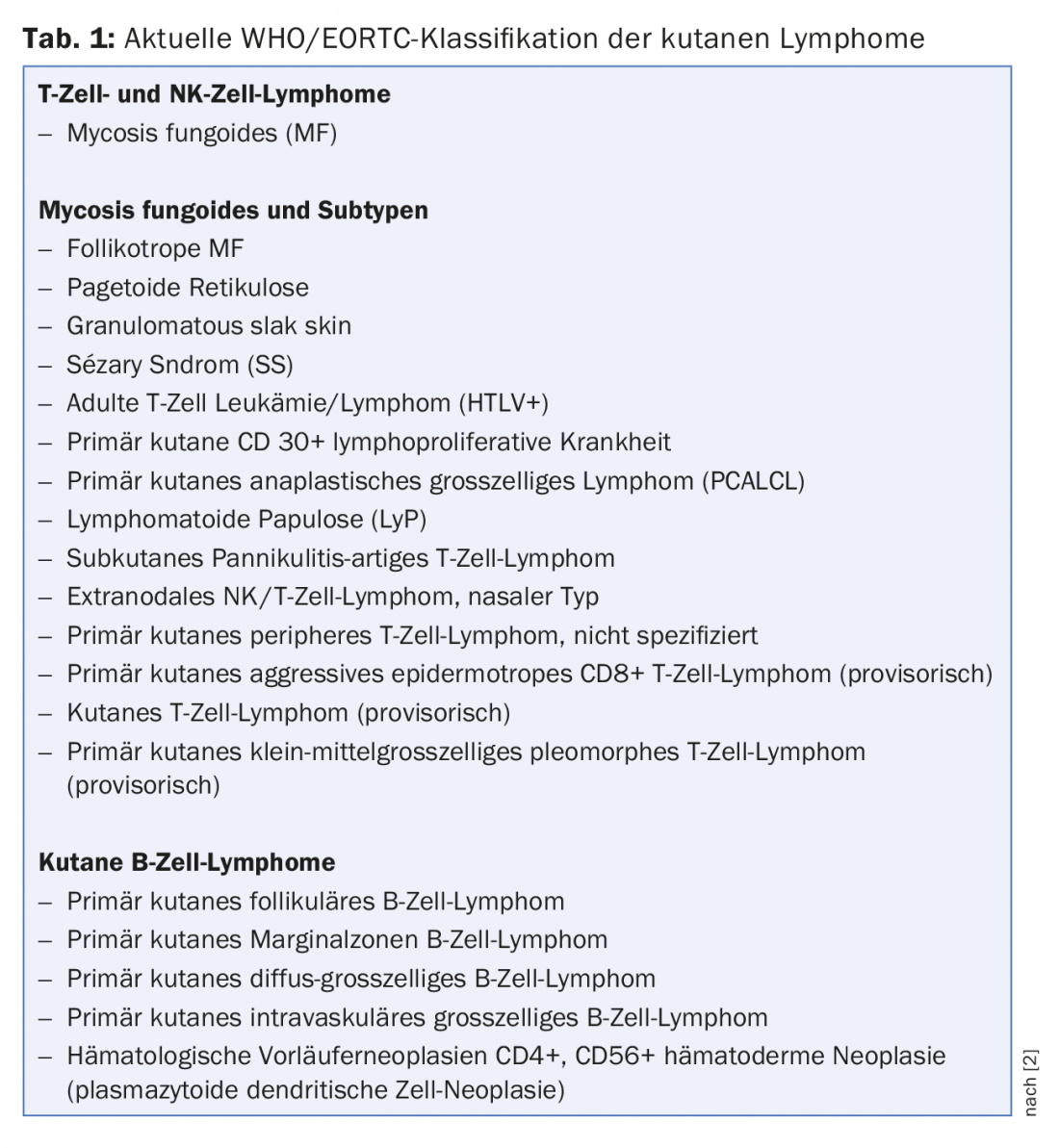

Cutaneous lymphomas are neoplastic diseases of the skin that occur when degenerate lymphocytes begin to grow uncontrollably. Known are especially the lymphomas of the lymph nodes. They can arise in all organs of the lymphatic system, including the spleen, thymus and tonsils. If the lymphocytes of the skin degenerate, skin lymphomas are formed. The cutaneous lymphomas are non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Depending on which type of lymphocyte becomes neoplastic, a distinction is made between cutaneous T- and B-cell lymphomas (Table 1).

This classification is also very useful, as T- and B-cell lymphomas differ significantly from each other in both clinical behavior and prognosis. T-cell lymphomas are generally more aggressive than B-cell lymphomas and thus have a poorer prognosis. The two cutaneous lymphoma types also differ in appearance: T-cell lymphomas usually appear generalized over the entire body, whereas B-cell lymphomas often present as solitary tumors (Fig. 1) [1].

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas and subtypes

The most common cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is mycosis fungoides (MF), nowadays hardly known as “usury lichen”. The misleading name mycosis fungoides was introduced in 1832 by Jean-Louis-Marc Alibert under the assumption that it was a fungal disease. However, the etiology of mycosis fungoides as well as all other cutaneous lymphomas remains unclear. Sunburns as in melanoma are not a possible cause in cutaneous lymphomas. Only high doses of radioactive radiation have been confirmed as a risk factor to date. The damage to the genetic material of lymphocytes caused by radiation leads to degeneration of cell division and clonal proliferation of cells. However, lymphocytes can also degenerate without external damage because they are rapidly dividing cells. In this context, spontaneous reading errors in the genetic material can lead to lymphomas [1].

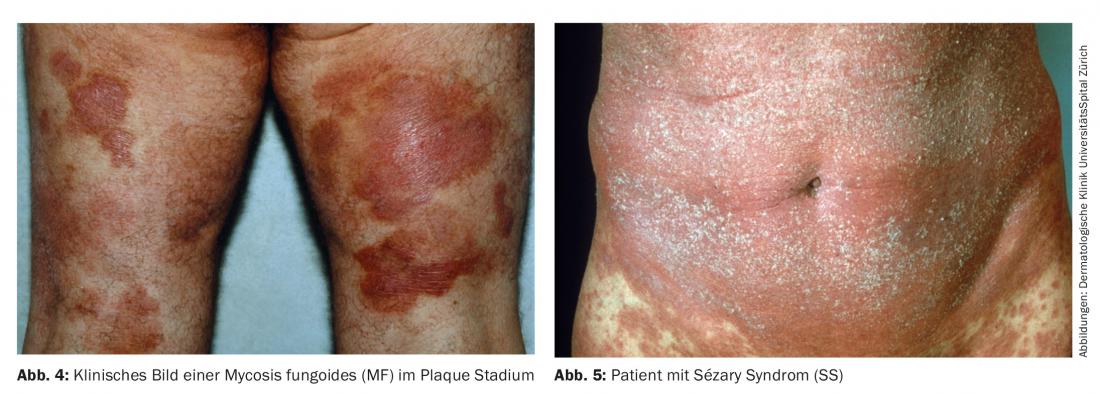

Mycosis fungoides (MF): Often shows a clinically phasic, typical course. The initial phase shows a slow, progressive eczema-like patch stage (Fig. 2). Clinically, the changes appear as eczematous skin lesions. This stage may persist for years and may then transition to the plaque stage (Fig. 4) . In this stage, the lesions are palpable and thickened. Further, the plaque stage may change to the clinically often very impressive tumor stage. However, these stages do not necessarily have to follow one after the other in a classical manner. For example, a transition from patch stage directly to tumor stage or to the erythrodematous form known as Sézary syndrome (SS) (Fig. 5) may be observed. The so-called leukemic variant of mycosis fungoides shows leukocytosis between 10,000-50,000 (rarely up to 100,000 leukocytes/ml). This is a serious clinical picture.

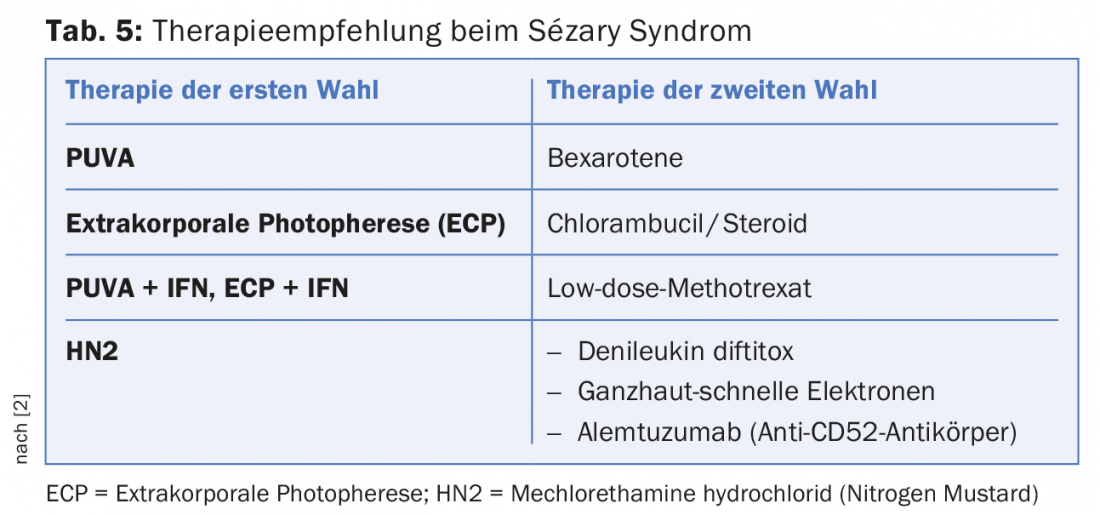

Sézary syndrome: Is understood as the leukemic variant of mycosis fungoides and also has a significantly worse prognosis than mycosis fungoides (Tab. 5). The so-called Sézary cells (atypical lymphocytes) are found in the peripheral blood. In addition, lymph node swelling is palpable in these patients and erythroderma is clinically apparent. The patient often experiences severe pruritus and the general condition is usually significantly reduced.

CD30+ large cell cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: Histologically, CD30+ large cell cutaneous T-cell lymphoma corresponds to that of nodal lymphoma of the same type. However, the prognosis is diametrically different and therefore must be treated therapeutically differently. The prognosis of nodal lymphomas of this type is very unfavorable and requires extensive chemotherapy. In contrast, in CD30+ large cell (pleomorphic or anaplastic) T-cell lymphoma of the skin, the prognosis is excellent and chemotherapy is contraindicated.

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

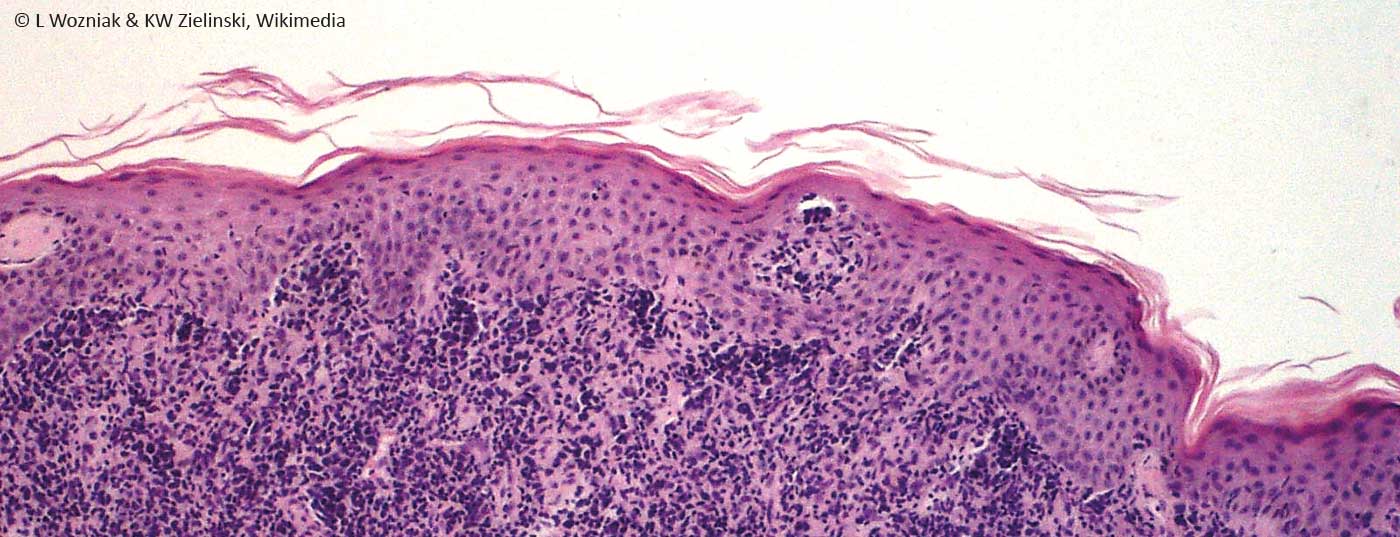

The rare B-cell lymphoma (about 20% of all cutaneous lymphomas) is usually a solitary, fast-growing tumor. Extracutaneous manifestations are very rare and thus the prognosis is often excellent. The nodules are usually indolent smooth nodules, which are usually solitary, sometimes disseminated. They are of red, partly brownish hue. Often there is a dermal, sometimes subcutaneous infiltrate with intact epidermis. The histologic picture of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas is quite monomorphic in contrast to T-cell lymphomas, which show great histologic diversity (Fig. 3) [1].

Lymphoma stages of T-cell lymphoma

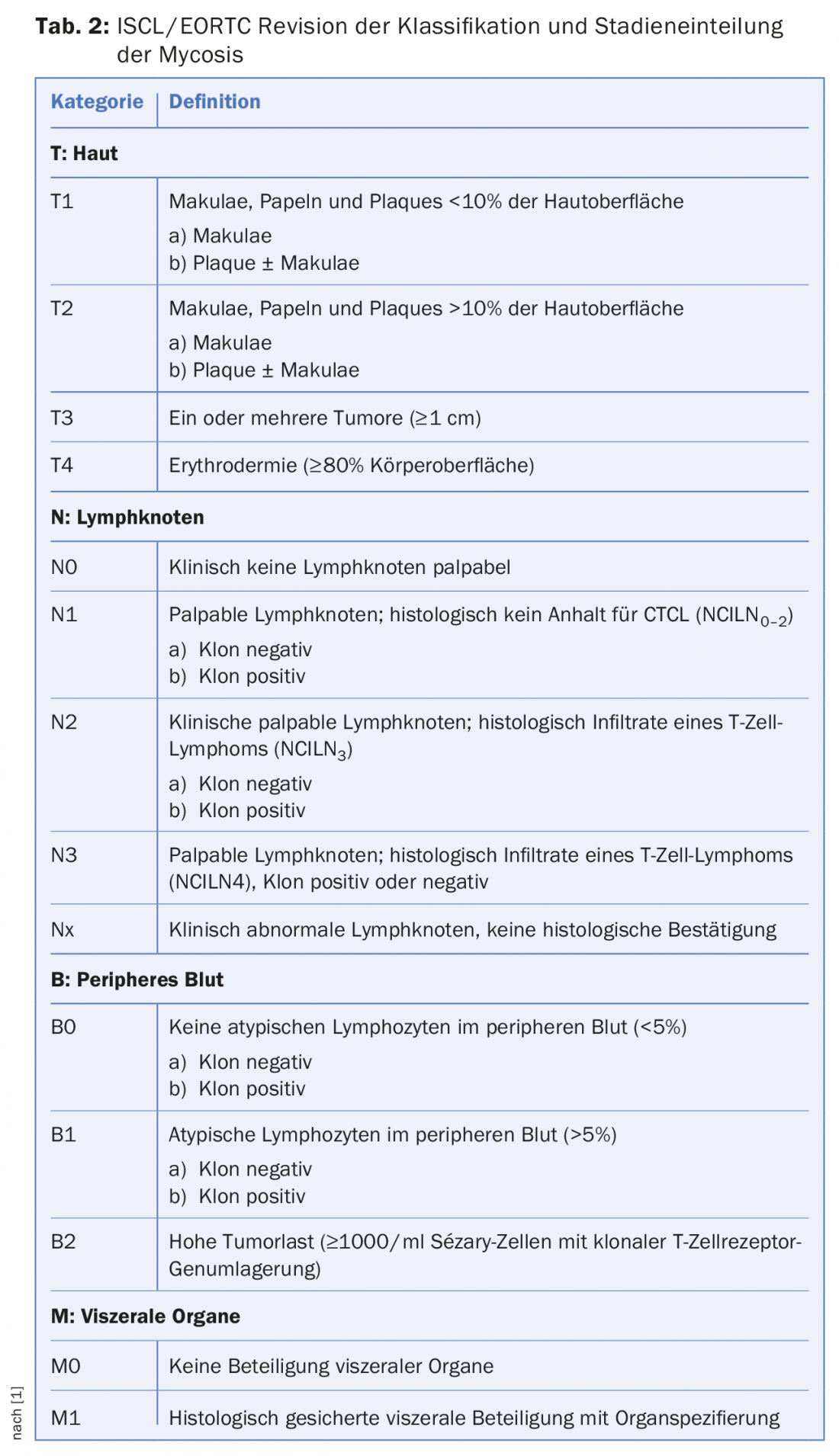

For the selection of a suitable therapy, it is necessary to recognize not only the type but also the stage in which the cutaneous lymphoma is located (Tab. 2). The stage provides information on how far the spread of cancer cells to other parts of the body has already progressed. In stage I, only parts of the skin are affected by the lymphoma. The skin has scaly, reddened patches, but no nodules. In stage II, either nodular thickenings are additionally visible on the skin, or the lymph nodes are enlarged. In stage III, cutaneous lymphoma covers almost the entire skin. The criterion for the last stage IV is the invasion of other organs with cancer cells. Either the lymph nodes can be affected or other organs.

Generally, cutaneous lymphomas occur in patients over 20 years of age. The cutaneous lymphomas with high malignancy show an age peak between 5-15 years and 60-70 years [5].

Diagnostics

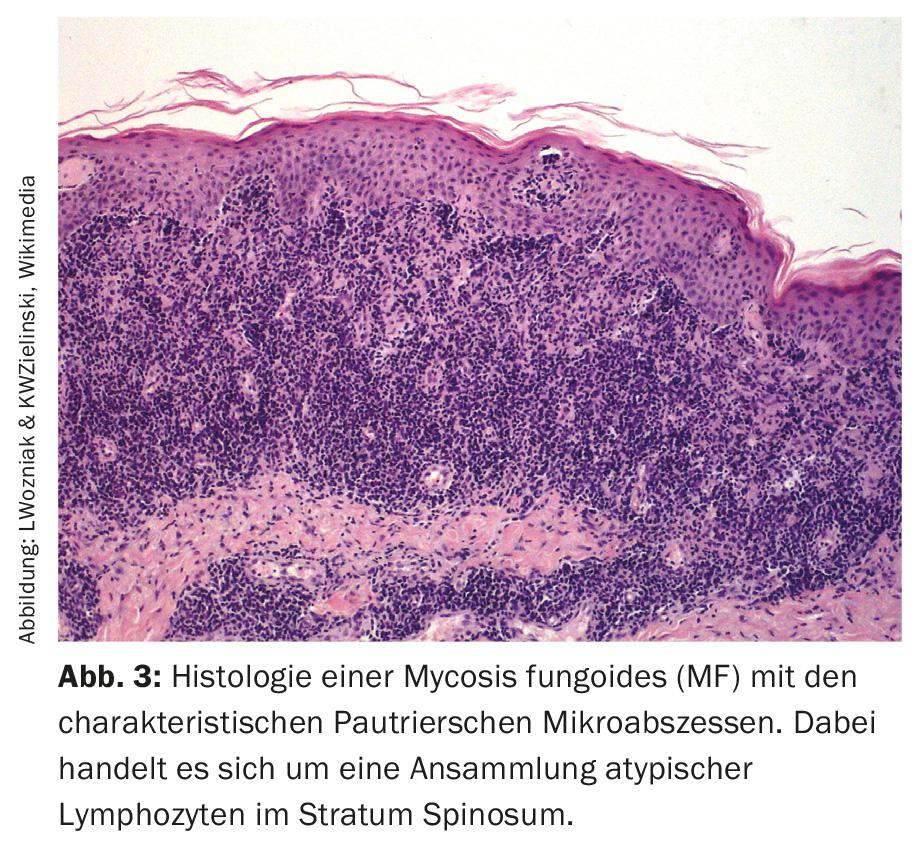

Cutaneous lymphomas are rare overall and often resemble other dermatologic diseases clinically. Thus, the primary stage of MF is often confusingly similar to contact dermatitis, so that the physician is often only alerted to cutaneous lymphoma by its clinically persistent course. These cutaneous neoplasms must be biopsy-proven. Today, monoclonal detection of lymphocytes is possible from the histological preparation. One can detect this clonality at the DNA, mRNA, and protein levels, detecting T cell receptor and immunoglobulin genes, respectively [1].

Clinical examination

Clinical examination for suspected cutaneous lymphoma includes a detailed evaluation of all skin lesions, as well as a lymph node status of all lymph node stations (palpations of lymph node stations, liver, spleen). Imaging modalities include abdominal and lymph node ultrasonography and chest radiographs. The examination depends on the stage of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma disease. Thus, whole-body CT examinations for T-cell l ymphoma are performed only from stage IIB in mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome (SS), adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, primary CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (nasal type), and primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (unspecified).

Among B-cell lymphomas, whole-body CT is indicated for primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (leg type) (PCBLT) and (PCBLT of other types), as well as primary cutaneous intravascular large B-cell lymphoma.

The diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma must always be confirmed histologically by biopsy. Immunohistochemical studies as well as the possibility of molecular biological studies, whereby the clonality of the lymphocytes can be investigated, is often very helpful for the differentiation from other inflammatory skin diseases.

Laboratory tests

If cutaneous lymphoma is detected, it is recommended that the following laboratory tests be performed:

- ESR and CRP, blood count, liver enzymes, creatinine, LDH, electrolytes.

- If necessary: immunoelecrophoresis, HTLV serology (especially for patients from abroad), Borrelia serology, special hematological examinations, further laboratory tests depending on the planned therapy.

- In erythrodermic T-cell lymphomas (suspected Sézary syndrome), a blood smear for Sézary cells is indicated.

B-cell lymphomas may require additional bone marrow biopsies: mandatory for PCBCL, optional for PCMZL and PCFCL.

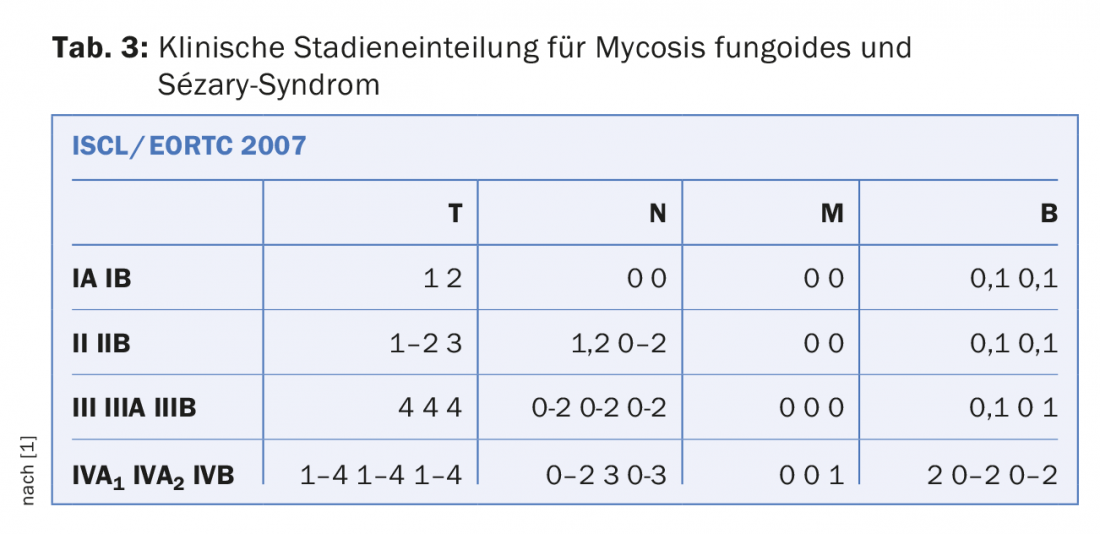

TNM Stages

The staging of cutaneous lymphomas CTCL is performed according to the TNM classification (Tab. 3). The classification provides information about the prognosis and thus indirectly about the necessary therapy. It cannot be emphasized enough that cutaneous lymphomas and nodal lymphomas have a completely different clinic and therefore must be evaluated completely independently (despite sometimes almost identical histology and classification). In the past, it was often the case that cutaneous lymphomas (CTCL) were over-treated. Often identical therapy regimens were used as for nodal lymphomas, which are not only ineffective but also harmful for the patient: Cutaneous lymphomas have a completely different prognosis and therapy than the histologically comparable nodal lymphomas! Thus, the TNM classification is also not 1:1 comparable with nodal lymphomas.

Forecast

The early stages of MF (IA-IIA) usually have a very good prognosis. The mean survival time is 10 to 20 years. Cutaneous lymphomas can be divided into three prognostic classes:

1. cutaneous lymphomas with good prognosis:

- Mycosis fungoides (MF)

- Pagetoid reticulosis

- Granulomatosis slack skin

- Primary cutaneous small-medium pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma (provisional).

- Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- Lymphomatoid papulosis

- Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.

- Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma

- Primary Cutaneous Follicular Lymphoma

2. cutaneous lymphomas with moderate prognosis:

- Folliculotropic MF

- Sézary syndrome

- Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (HTLV+)

- Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type/other types.

3. cutaneous lymphomas with poor prognosis

- Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (nasal type)

- Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma (provisional).

- Cutaneous/T-cell lymphoma (provisional)

- Primary cutaneous intravascular large B-cell lymphoma.

- Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma with hemophagocytosis.

- CD4+,CD56+ hematoderma neoplasia

Therapy

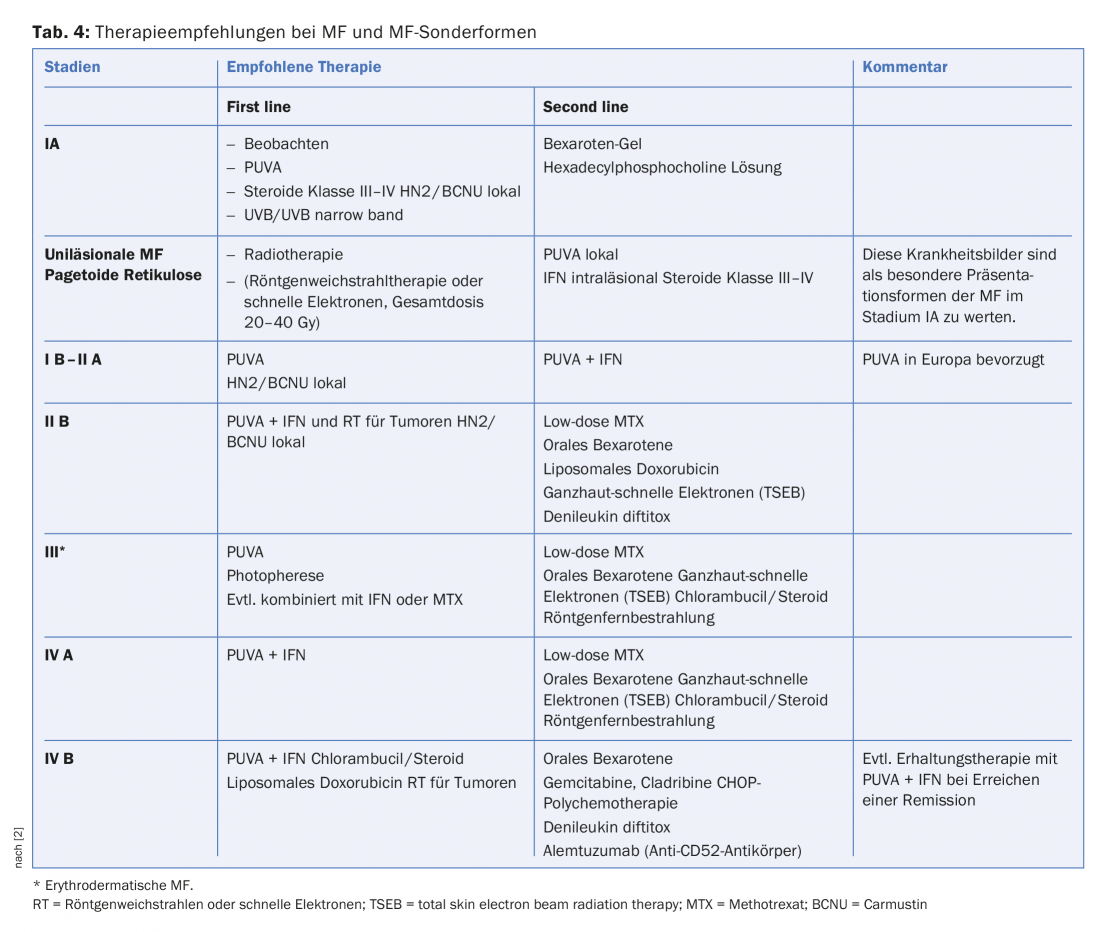

Therapy of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: The early stages of mycosis fungoides, such as the corner-cematous stage and partly also the patch stage, can often be successfully treated for years with local steroids (sometimes combined with PUVA or narrowband UVB light). If there is no response, interferon is then used as the first system therapy. Therapies for the higher stages of cutaneous lymphomas are summarized in Table 4 .

Therapy of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCL)

Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphomas and germinal center lymphomas: Low-grade malignant cutaneous B-cell lymphomas correspond to nodal mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas because of their morphologic similarity. Because of the similarities, low-malignant CBCL are referred to as skin associated lymphoid tissue (SALT) lymphomas by some authors. The prognosis of this group of diseases is generally extremely favorable. Since infectious particles (Borrelia DNA) can be detected in some cases, initial treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotic is recommended. Because Borrelia detection can be falsely negative and is also costly, patients are recommended doxycyline therapy at a dosage of 2× 100 mg p.o. daily for three weeks.

Surgical excision is recommended for small lesions, and radiotherapy should be considered for larger ones. Recommended total dose is 20 Gy-35 Gy, fractionated in single doses, 1 to 2× 4 Gy, then 2 Gy to total dose, 2 to 3× per week. Alternatively, intralesional interferon injections are recommended or the use of rituximab, a humanized antibody directed against the B-cell antigen CD20. Intralesional therapy is also possible with this substance, with only 20% of the systemically necessary dose having to be used.

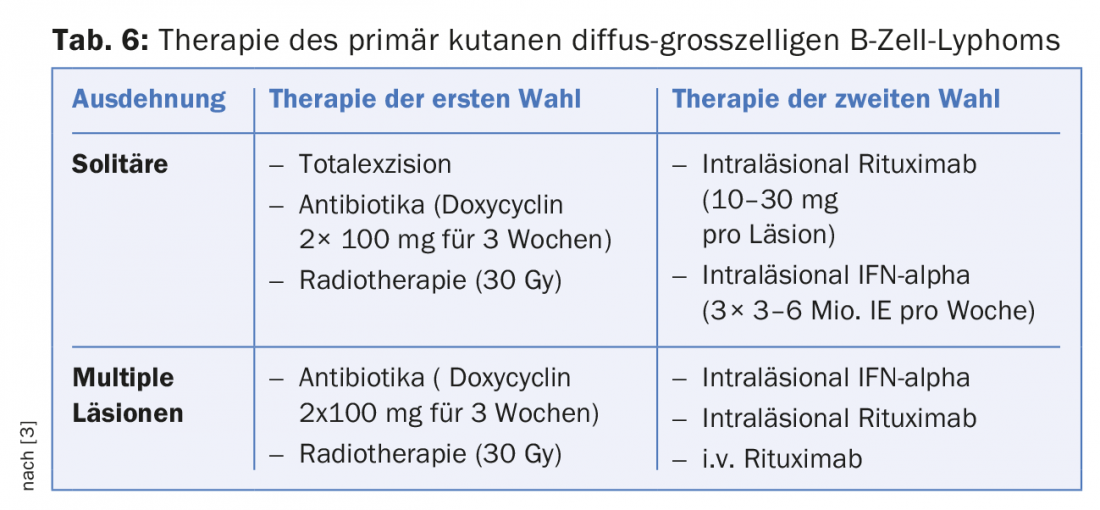

In contrast to cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with a follicular structure, germinal center lymphomas and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas show a comparatively poor prognosis. Radiotherapy is recommended initially, with doses of at least 30Gy required. Polychemotherapy combined with rituximab may be considered for recurrences [3].

Psycho-oncological aspects

The few studies on the psychological and social well-being of cutaneous lymphoma patients show a drastic reduction in quality of life. In particular, treatment with steroids and interferon seems to trigger depressive moods and anxiety in some patients. Patients with MF mainly described their fatigue and the occurrence of sleep disturbances as limiting factors. The impairment in dealing with fellow human beings, at work and in personal relationships is also very stressful due to the “visibility” of the diagnosis [1].

Outlook

A new therapeutic approach of cutaneous lymphomas could be photodynamic therapy (PDT). This therapy is already successfully used in the treatment of actinic keratoses and Bowen’s disease. Professor Hunger’s group in Bern has undertaken a pilot trial in MF patients in early stages of the disease. The results showed that a response was achieved in 73% of treated lesions. The group concludes that patients with early MF stages can be successfully treated with PDT with excellent cosmetic results [4].

Literature:

- www.derma.de/de/daten/leitlinien/leitlinien/kutane-lymphome

- www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/032-027l_Kutane_Lymphome_2014-verlaengert.pdf

- medicalforum.ch/docs/smf/archiv/de/2009/2009-42/2009-42-379.pdf

- Derm. Hel. 2016;28(7): 28-32

- www.dermatologie.usz.ch/ueber-die-klinik/Documents/USZ_Lymphom_A5.pdf

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2016; 26(6): 6-12