With the introduction of the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor ruxolitinib, therapy for myelofibrosis has changed dramatically in recent years. Nevertheless, further innovation is needed, especially in the second line. Promising data on new treatment options were presented at the last ASH Annual Meeting in December 2020.

In addition to stem cell transplantation, effective therapeutic tools for myelofibrosis have long been lacking. Although the development of JAK inhibitors has enabled important steps to be taken in the fight against the disease in recent years, a cure is still not in sight. Perhaps the use of new, innovative agents will now bring at least longer-term symptom control within reach.

State of the Art

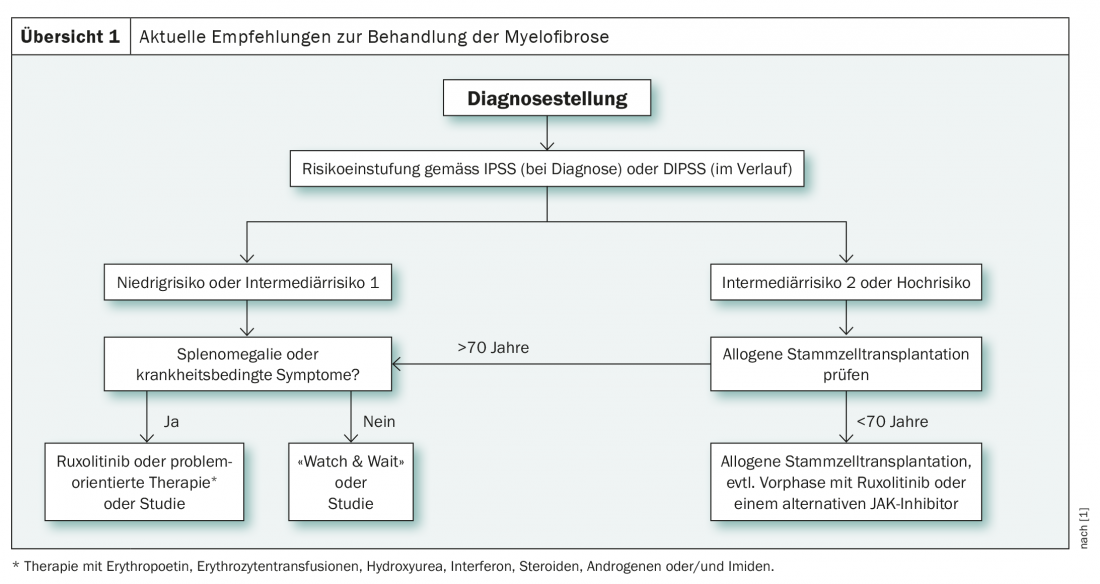

The decisive factor for the choice of therapy in diagnosed myelofibrosis is risk stratification, which is performed at diagnosis according to the IPSS(International Prognostic Scoring System) and later using the DIPPS (Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System) in four groups (low risk, intermediate-1, intermediate-2 and high risk). These are clinical scoring systems, which can be supplemented by other classification methods as needed. For example, the GIPSS (Genetically Inspired Prognostic Scoring System) also takes into account cytogenetic and molecular genetic factors. These can facilitate the decision for or against stem cell transplantation in unclear cases and are therefore particularly helpful in the intermediate-1 risk group [1]. In this group, according to new international guidelines, stem cell transplantation is recommended for patients under 65 years of age if certain criteria are met. These include refractory transfusion-related anemia, circulating blasts >2%, and unfavorable cyto- or molecular genetics [2].

In contrast to the intermediate-1 risk group, the recommendation for allogeneic stem cell transplantation is clear in the intermediate-2 as well as in the high-risk group in patients younger than 70 years (overview 1) . In addition, since 2017, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib has been increasingly used. This is particularly used in the preliminary phase of stem cell transplantation and in the treatment of low to intermediate risk individuals, especially in the presence of disease-related symptoms or splenomegaly. As an alternative to ruxolitinib therapy, symptomatic low- and intermediate-risk patients can also be treated in a problem-oriented manner. This approach includes the use of erythropoietin, red blood cell transfusions, hydroxyurea, and steroids, among others [1].

Ruxolitinib, as well as other JAK inhibitors, are thus on the rise in both the low- and high-risk settings. On the one hand, these agents serve to control symptoms, and on the other hand, according to current studies, they are able to support stem cell transplantation. Nearly ten years after the first trial data on ruxolitinib, the JAK inhibitor is now shown to have sustained effects on splenomegaly as well as disease-related symptoms of myelofibrosis, with long-term improvement in quality of life [3,4]. At the ASH Annual Meeting 2020 , the potential extension of survival time of the drug was also discussed, for which there are more and more promising data, albeit so far only retrospective [5]. Nevertheless, progression, especially to acute myeloid leukemia, remains an important problem [5].

Room for improvement

Despite the significant progress in therapy over the past years, there is still much room for improvement. Especially in the case of ruxolitinib treatment failure and drug intolerance, the options are currently still very limited. While primary resistance is rare, inadequate response and loss of response are more common. For example, the median duration of action of ruxolitinib on splenomegaly is just over three years, which often limits the use of the drug over time and raises the question of complementary therapeutic options [3,4]. This Medical Need also emerges from the discontinuation rates of ruxolitinib therapy analyzed in a recently published study, which were 50% to 60% after three years [6]. Median survival after drug discontinuation is only 14 months and is further shortened in the presence of clonal aberrations or low platelet counts [7].

Moreover, the effect of the substance on anemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia is often insufficient. Alternative therapeutic strategies are urgently needed to adequately address the cytopenias that occur in the setting of myelofibrosis. After all, nearly 40% of patients have hemoglobin levels below 10 g/dL at diagnosis and 20% are already transfusion dependent at this time [8].

The positive effects of ruxolitinib also cannot hide a clear shortcoming: True remissions under current therapy are extremely rare in the real world setting [9]. This may be due in part to the mechanism of action, as the JAK2V617F target mutation is not solely responsible for the development of myelofibrosis. Thus, elimination of the disease cannot be expected with appropriate blockade by a JAK inhibitor.

A look into the future

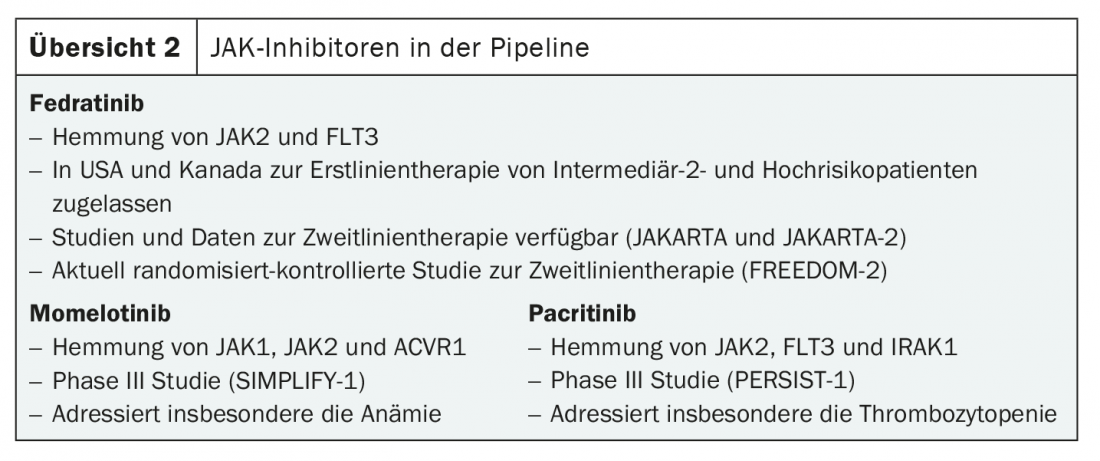

Although a cure by this substance class is mechanistically hardly possible, hope in the treatment of myelofibrosis continues to lie primarily in the development of new JAK inhibitors. At the ASH Annual Meeting 2020 , data were presented on three new substances targeting JAK (overview 2) . These are expected to complement ruxolitinib therapy in the future. Fedratinib is already approved for first-line therapy in the U.S. and Canada, and Phase III trials are ongoing for the use of momelotinib and pacritinib.

That fedratinib is also promising in second-line treatment is shown by results from the JAKARTA-2 trial [10]. Here, the drug demonstrated strong efficacy on splenomegaly and disease-related symptoms in all subgroups pretreated with ruxolitinib. The response rate was 55.4%. Fedratinib could therefore soon be used in ruxolitinib resistance and intolerance, especially if the results from JAKARTA-2 are confirmed in the currently ongoing randomized-controlled FREEDOM-2 trial – a prerequisite for approval in Switzerland and Europe.

As new therapeutic options are developed, various questions also come to the table. For example, the optimal time to switch to an alternative JAK inhibitor needs to be evaluated. So far, the rule of thumb has been that therapy with ruxolitinib should be phased out before the switch in order to avoid a rebound. Today, a full three months is waited for response before treatment is considered a failure. The increasing number of options also complicates the choice of therapy. Individual preferences, for example regarding the frequency of use, as well as the respective spectrum of side effects, will probably be allowed to play a greater role in the future.

Source: 62nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH Annual Meeting), December 5-8, 2020, virtual conduct.

Literature:

- Griesshammer M, et al: Onkopedia Guidelines: Primary Myelofibrosis (PMF). www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/guidelines/primaere-myelofibrose-pmf/@@guideline/html/index.html (last accessed on 03.01.2021)

- Barbui T, et al: Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia 2018; 32(5): 1057-1069.

- Verstovsek S, et al: Long-term treatment with ruxolitinib for patients with myelofibrosis: 5-year update from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 COMFORT-I trial. J Hematol Oncol 2017; 10(1): 55.

- Harrison CN, et al: Long-term findings from COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study of ruxolitinib vs best available therapy for myelofibrosis. Leukemia 2016; 30(8): 1701-1707.

- Al-Ali HK, et al: Primary analysis of JUMP, a phase 3b, expanded-access study evaluating the safety and efficacy of ruxolitinib in patients with myelofibrosis, including those with low platelet counts. Br J Haematol 2020; 189(5): 888-903.

- Harrison CN, Schaap N, Mesa RA: Management of myelofibrosis after ruxolitinib failure. Ann Hematol 2020; 99(6): 1177-1191.

- Newberry KJ, et al: Clonal evolution and outcomes in myelofibrosis after ruxolitinib discontinuation. Blood 2017; 130(9): 1125-1131.

- Naymagon L, Mascarenhas J.: Myelofibrosis-Related Anemia: Current and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Hemasphere 2017; 1(1): e1.

- Gill H, et al: Myeloproliferative neoplasms treated with hydroxyurea, pegylated interferon alpha-2A or ruxolitinib: clinicohematologic responses, quality-of-life changes and safety in the real-world setting. Hematology 2020; 25(1): 247-257.

- Harrison CN, et al: Janus kinase-2 inhibitor fedratinib in patients with myelofibrosis previously treated with ruxolitinib (JAKARTA-2): a single-arm, open-label, non-randomised, phase 2, multicentre study. Lancet Haematol 2017; 4(7): e317-e24.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(1): 32-33 (published 2/24/21; ahead of print).