Resistance to macrolides and gyrase inhibitors has the greatest impact on eradication success in H. pylori infection. Clinical risk factors such as age, smoking, and compliance also play a role in treatment failure.

Worldwide, approximately 50% of all people are infected with H. pylori [1,2]. Transmission usually occurs during infancy. Thus, once acquired, the infection often persists into old age without therapy, which explains why today’s 70-80 year olds are more than 50% infected, while today’s 20-30 year olds are significantly less than 50% infected (so-called cohort effect). The risk factor for person-to-person transmission in Western countries is considered to be direct (“oro-oral”) contact; in developing countries, other routes are also dominant (“fecal-oral”). The prevalence of H. pylori in Central Europe is currently between 5% (children) and 25-40% (adults). It is higher among migrants (35-85%). As social and hygienic living conditions (i.e. also the number of new infections) have continuously improved in Western countries, the infestation rate of the total population is decreasing. As a result, age-specific H. pylori-associated mortality of both gastric cancer and peptic ulcer decreases.

Symptoms – disease manifestations

Clinical symptoms such as upper abdominal pressure, feeling of fullness, (fasting) pain, nausea, dizziness are non-specific (irritable stomach or functional dyspepsia, FD). Symptoms of H. pylori infection are no different from other causes such as stress, gastroduodenal toxic drugs such as aspirin (ASA) in particular, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The extent of the complaints is also not indicative of the severity of the endoscopic findings (gastritis without/with erosions, ulcer disease). Ulcer bleeding due to H. pylori is not clinically different from that due to ASA/NSAIDs or other causes.

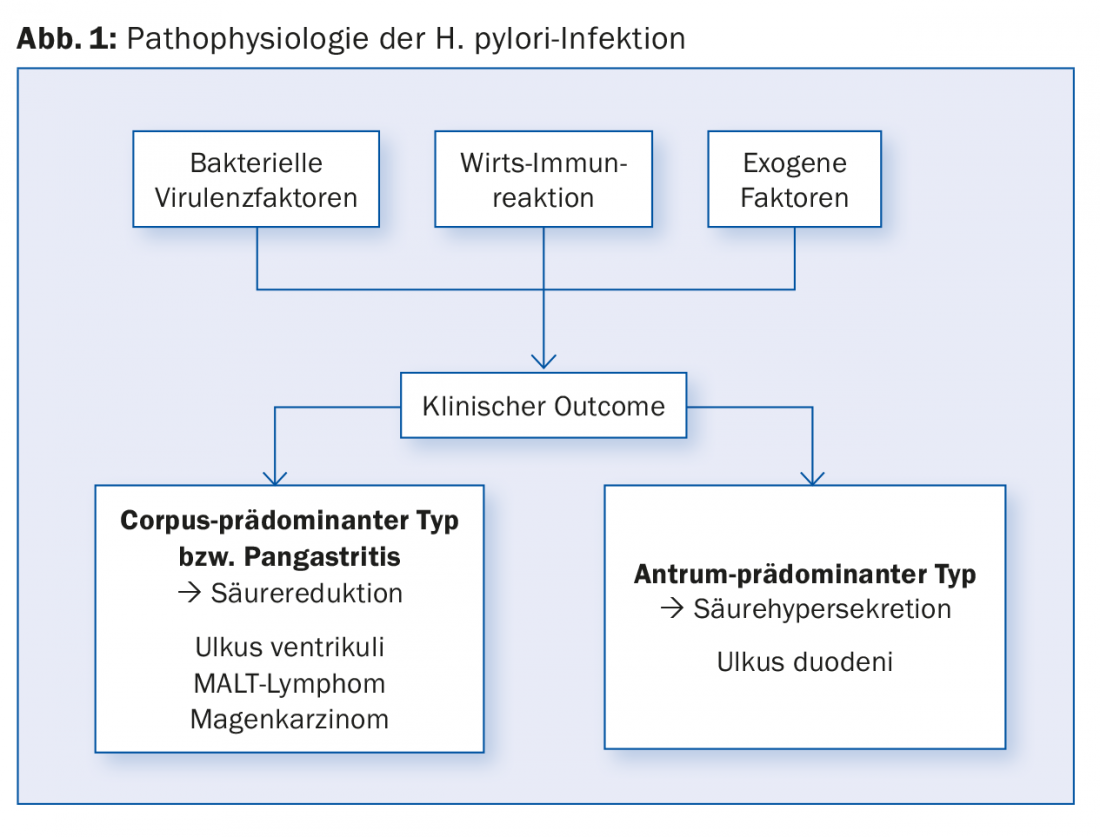

Approximately 20% of infected individuals develop ulcer disease (duodenal ulcer, DU; gastric ulcer, GU) during their lifetime, and depending on the region, 1-2% also develop gastric carcinoma (GC) or MALT lymphoma [1,2]. The patient’s history may indicate that there is a family history of gastric cancer or a history of ulcer disease. The remaining infected individuals often have only minor symptoms without endoscopically visible lesions or are completely asymptomatic. Gastritis distribution type is critical in assessing gastric carcinoma risk (Fig. 1) . In general, any gastroduodenal ulcer/gastric carcinoma remains suspicious of H. pylori infection until proven otherwise, especially the younger the patient.

Diagnostics

The clinical situation determines the choice of tests required for clarification [1–5]. Eligible:

- Urease-based breath test (UBT)

- Stool Antigen Test (SAT)

- Urease rapid test (HUT) and histology (HISTO), if necessary with microbiological culture and phenotypic or PCR with genotypic resistance determination in the context of endoscopy.

- Serology (incl. immunoblot).

Primary detection: Except for serology, all tests mentioned can be used, specificity is >95%. With the exception of microbiological culture, the sensitivity (without falsifying factors) is approximately 90%, and a positive test is sufficient to detect the infection. If esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy must be performed for clinical indication, one will rely on the bioptic tests (HUT and histology, PCR/culture if necessary); if only screening for H. pylori is to be performed because of rather “blanched” symptoms, one will use the stool test or breath test (equieffective); patient preference is usually for the stool test.

Therapy planning incl. Resistance determination: Until recently, this was the domain of microbiological culture. Due to the cumbersome transport procedure, the long cultivation and phenotypic resistance testing (two to three weeks) and numerous interfering factors, the cultivation rate is only around 70%, depending on the laboratory. Here, PCR with genomic testing for macrolide/and fluoroquinolone resistance has a clear advantage: The determination can also be made from bacteria that have already died in some cases and is theoretically available 24-48 hours after taking the biopsy. The accuracy of the resistance determination corresponds to the culture. The only disadvantage: resistance analyses for other antibiotics (such as metronidazole, rifabutin) are not possible with it.

Eradication control: This is the domain of the stool antigen test (or breath test). If for clinical reasons, e.g., gastric ulcer healing must be monitored endoscopically, the bioptic tests can of course also be used, but all tests must be negative in order to speak of successful eradication.

Special situations leading to incorrect test results [5]:

- In gastric malignancies (Ca, MALT lymphoma) with negative H. pylori detection by standard methods, performing serology may make sense.

- Interfering factors that must be observed: While false-positive tests are rare, H. pylori detection can be false-negative if the following confounding factors are not observed: The intake of proton pump blockers (PPI) or antibiotics (already for more than three to five days) leads to false-negative test results in approx. 80%, therefore it is essential to discontinue the PPI at least one (better two) or an antibiotic at least two (better four) weeks before the test is performed. H2 blockers or antacids usually hardly interfere and can be given alternatively as “bridge therapy”.

- Insufficient number of biopsies for HUT and histology Ò one each from gastric antrum and corpus for HUT and one (better two) each for histology.

- Taking a test in case of acute gastrointestinal bleeding Ò Checking again in the interval.

- Breath test or stool test in case of partially resected stomach (also partly in case of gastric emptying disorder) -> here the bioptic test is to be preferred.

Treatment of H. pylori infection [1–5]

Disease patterns/treatment indications associated with H. pylori infection: An overview is given in Table 1 [5]. Eradication accelerates ulcer healing in one-sixth of patients with GU and one-fifth with DU and prevents ulcer recurrence (Number Needed to Treat, NNT of 3 for GU and NNT of 2 for DU). The benefit remains controversial, especially for the majority of patients with NUD therapy; here, the benefit of permanent symptomatic improvement from eradication (versus placebo) is about 5-10% (NNT 10-20), which is, however, no worse than long-term PPI therapy. Prophylaxis of gastric cancer by H. pylori eradication is more successful the earlier it is performed and when high-risk patients in particular are treated.

Causative factors for treatment failure include [5]:

- Antibiotic resistance (by far the most important: risk difference absolute approx. 20-50%, corresponding to NNT 2-5); mostly due to previous antibiotic therapy for other infections, e.g. lung, urinary tract, gynecological

- Too short therapy duration with tripleregimes

- CYP2C19 wild-type status for appropriately metabolized PPIs such as omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole (does not apply to esomeprazole, rabeprazole, dexlansoprazole).

- Smoking

- Young age (under 50-60 years)

- NUD (non-ulcer disease)

- Lack of compliance due to side effects (varies greatly by regimen, probiotics may improve tolerability).

An absolute risk difference of 8-12% (corresponding to an NNT/NNH of approximately 10) applies to all these clinical or pharmacological influencing factors.

Recommendations for resistance testing [2–5]:

- Mandatory H. pylori resistance testing after single/multiple treatment failure.

- Optional before initial therapy if positive allergy situation, presence of mentioned clinical risk factors, frequent previous antibiotic therapy.

Otherwise, resistance testing is not mandatory (cost-benefit consideration). To save costs, I recommend waiting for the rapid test. If this is positive, the biopsy can be taken from the HUT and sent to the laboratory for PCR resistance testing even after 48-72h, which greatly increases the positive yield and only fails in about 10% of patients.

Recommendations for so-called “first-line or primary therapy”: recommended regimens with dosages are listed in Table 2. With the introduction of one-week triple therapies in the early 1990s, these became the standard of care for primary treatment in most Western countries. The basis for the recommendation was the view in the so-called Maastricht I, II, III (1997, 2002, 2007) consensus conferences [1] that one-week triple therapies of PPI, clarithromycin, and either amoxicillin or metronidazole have success rates of 85-90%, and macrolide/clarithromycin resistance rates before therapy are less than 15-20%. However, current eradication rates in numerous meta-analyses average only 75% for a triple regimen, which is unacceptable [5]. Macrolide resistance is often locally above 15%, in the period 2014-2017 according to own local data from Aarau (n=200) exactly 20%. Clinically, it is almost impossible to reliably record all previous antibiotic therapies (i.e., not only H. pylori-initiated ones) of a patient, so that often a resistance situation already underlies [4,5]. Unfortunately, none of the current guidelines takes this into account, so that many microbiologists, in contrast to the other clinicians, demand resistance testing even before the first (!) eradication therapy, since the distinction between “primary and secondary therapy” of H. pylori infection [1–3] does not do justice to reality [5].

Therefore, the trend is clearly towards quadruple rather than triple therapies, even though these unfortunately remained again in the updated German (DGVS) guideline 2016 [3]. In my opinion, the following should be applied as a matter of priority (Tab. 3) a non-bismuth-containing, so-called concomitant seven- to ten-day therapy with PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole (PPI-ACM) bismuth-containing combination therapy with PPI and tetracycline/metronidazole/bismuth (Pylera®, PPI-BMT/Pylera®) for 10-14 days Reserve therapy after failure of either of the above regimens or if Pylera® is not available: PPI plus amoxicillin, levofloxacin (PPI-AL).

Therapy of eradication failure (Tab. 3) [2–5]: In general, this depends on the primary regimen used, which is why no general recommendation can be made; at the latest, resistance testing should be carried out in advance! With single/multiple unsuccessful eradication, resistance rates increase dramatically (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, in the absence of resistance information, it is recommended to use one of the two remaining regimens mentioned. If this is not sufficient, resort may be made (rarely) to a ten-day combination with PPI-amoxicillin-rifabutin or high-dose three-times-daily dual therapy with PPI-amoxicillin for two weeks.

From clinical experience, it can be concluded that youthful age, active smoking, and non-ulcer-associated H. pylori infection should give reason to rather prolong the duration of therapy (5-10% gain in success rate). Conversely, if compliance is poor, it is imperative to choose a regimen that is as short-lasting/easy to take as possible. If the patient has to take 20 + 120 tablets in ten days with the PPI-Pylera® regime, but only 56 tablets over seven days with the “concomitant” quadruple therapy, the preference is clearly set. It is known from numerous studies that the PPI-Pylera® regimen performs dramatically poorly when taken for less than seven days, and the “concomitant” regimen loses efficacy at less than five days of therapy.

Take-Home Messages

- The decrease in new H. pylori infections in Central Europe is directly related to the decrease in mortality from gastric cancer and peptic ulcer disease.

- The phenotype of gastritis determines the clinical entity in terms of acid association.

- If there is no obligatory H. pylori eradication indication, testing should be refrained from if no therapeutic consequence results from it. H. pylori diagnosis is strongly discouraged during ongoing therapy with proton pump inhibitors.

- Clinical risk factors should be included in therapy regimen selection or stratification, insofar as they are easily ascertainable (age, smoking, endoscopic diagnosis, allergies, compliance).

- Resistance to macrolides and gyrase inhibitors has the greatest clinical impact (across all regimens involved) on eradication success, favoring genotypic resistance testing by PCR already in primary diagnostics in at-risk groups (antibiotic allergies, frequent previous antibiotic therapies, documented H. pylori eradication failure).

Literature:

- Fischbach W, et al: S3-guideline “helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal ulcer disease” of the German society for digestive and metabolic diseases (DGVS) in cooperation with the German society for hygiene and microbiology, society for pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition e. V., German society for rheumatology, AWMF-registration-no. 021/001. Z Gastroenterol 2009; 47(12): 1230-1263.

- Malfertheiner P, et al: Management of Helicobacter pylori infection – the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2017; 66: 6-30.

- Fischbach W, et al: S2k-guideline Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal ulcer disease. Z Gastroenterol 2016; 54: 327-363.

- Graham DY, Lee YC, Wu MS: Rational Helicobacter pylori Therapy: Evidence-Based Medicine Rather Than Medicine-Based Evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 177-186.

- Driver G: Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal ulcer. An updated commentary of the German S3 guideline. Med World 2010; 61: 204-212.

- Wüppenhorst N, et al: Prospective multicentre study on antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Germany. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2014; 69(11): 3127-3133.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(9): 34-38