Zika is on the minds of the world’s public. However, the interpretation of Zika diagnostics is not trivial. Due to cross-reactivity, interpolation of Zika IgM/IgG antibodies is difficult. Dengue and other flaviviruses can cause false positive results. Opportunities for more precise diagnostic procedures are emerging.

On May 15, 2015, the Ministry of Health in Brazil confirmed that Zika virus (ZIKV) was circulating in the country. Cases have been confirmed in Rio Grande do Norte and Bahia States [1,2].

Already on June 8, 2015, the first imported and documented case of Zika in Switzerland presented itself in our practice [3]. This was a 44-year-old woman with a three-day history of a flu-like infection with chills, headache, fever up to 38.6 °C, and painful swelling of the cervical, retroauricular, occipital, and inguinal lymph nodes. The symptoms appeared on June 5, five days after she returned from a 12-day vacation in Canoa Quebrada, Ceará state, in the northeastern part of Brazil. In the coming months, numerous cases of cicada were registered worldwide.

Zika diseases are nothing new

Zika virus was first isolated 70 years ago (1947) in Uganda from a rhesus monkey [4]. In 2007, Zika spread outside of Africa and Asia for the first time and was considered an emerging germ more than a decade ago [5]. It is an RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus, closely related to other flaviviruses with public health relevance, such as dengue virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, yellow fever virus, or West Nile virus [6]. Vectors are the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, but Aedes albopictus is also thought to be a transmitting mosquito vector [7]. Approximately 75% of cicada cases go undetected due to the very short duration of illness and very mild influenza-like symptoms. However, the potential to cause more serious disease is currently unknown. Neurological complications up to Guillain-Barré syndrome or sudden bilateral blunt and metallic hearing could be Zika-associated [8]. However, the most important reason why Zika is of concern to the world public is its much-discussed link to neonatal microcephaly. It should be noted, however, that most conditions with high-febrile states in the first trimester can be associated with microcephaly.

Course for the first patient

Early on, on June 8, , the patient presented with a maculopapular rash and rubelliform exanthema on the décolleté that persisted for five days. On day 5 of illness, she developed very painful swelling of the joints with increasing arthralgia of the wrists and finger joints. Blood pressure, pulse, general examination of heart, lungs, abdomen as well as neurological examinations were without pathological findings. Hematology/blood chemistry also showed no abnormalities during the course. C-reactive protein, liver function tests, and other chemistry values also remained within the reference range during the course of the disease. The often described conjunctivitis did not appear. By day 13 after the onset of symptoms (June 18, ), almost all symptoms had disappeared. The remaining back pain and headaches lasted another two weeks. The patient then recovered completely (restitutio ad integrum).

Diagnostics

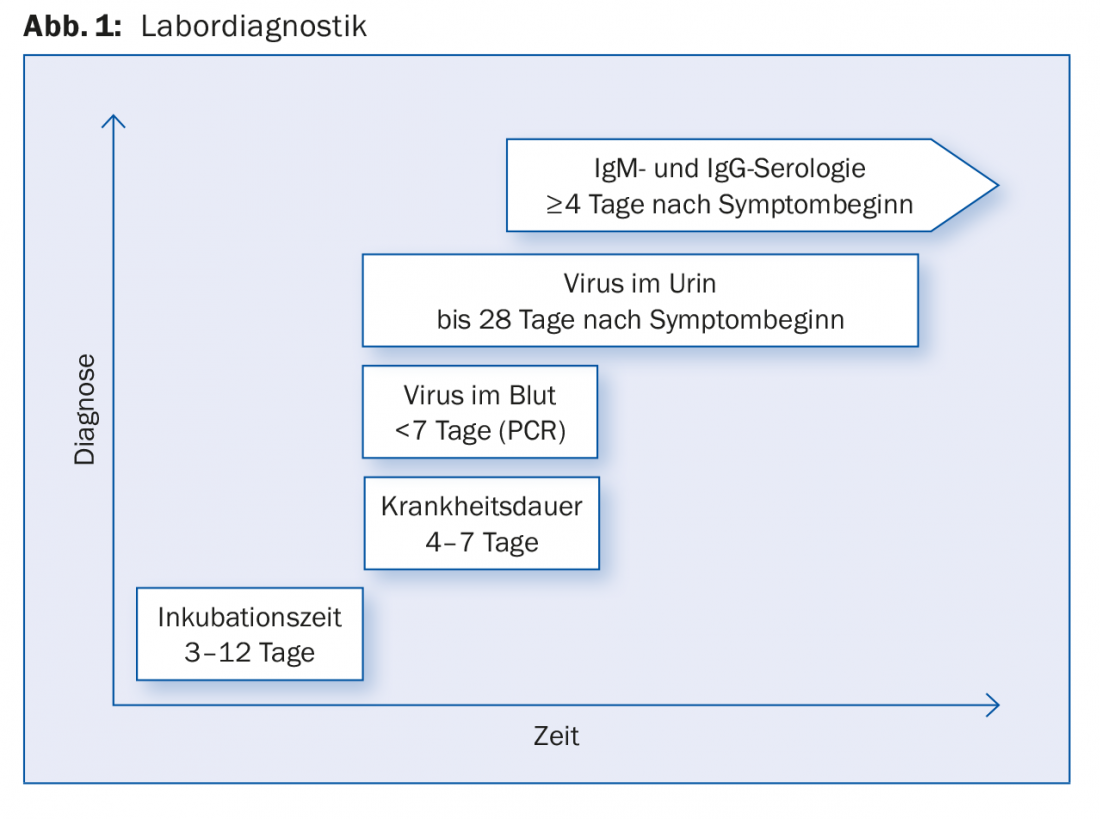

Clinical differential diagnosis primarily includes influenza infection and, in travelers returning from risk areas, the emergency exclusion of malaria tropica. Furthermore, dengue fever or chikungunya fever may be considered as a differential diagnosis. Zika virus has a very short viremic period during the first three to five days after symptom onset [9]. Within this time, very few cases present themselves in practice. IgM and IgG antibodies are measured (Fig. 1).

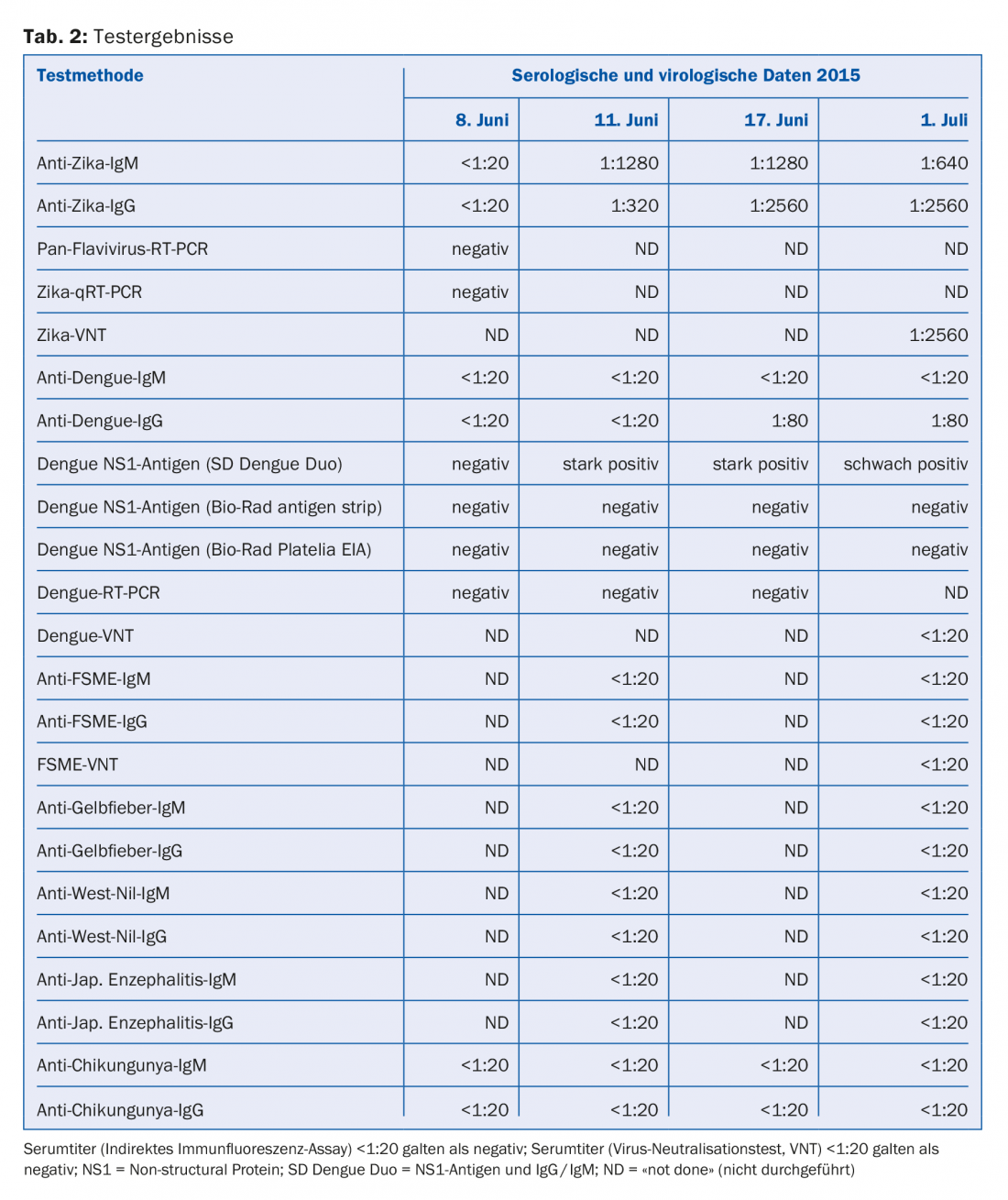

However, due to cross-reactivity, interpolation of Zika IgM/IgG antibodies is difficult and often misleading. In addition, not only dengue leads to false positive results, but also other flaviviruses such as TBE, West Nile to yellow fever or even vaccinations against flaviviruses (TBE/yellow fever). Another case showed detectable antibodies against all flaviviruses (tab. 1). In this case, the detection of specific Zika antibodies was only possible after one year, after appropriate test methods became available.

Two years ago, specific antibody tests (e.g. the indirect immunofluorescence test) could only be offered by highly specialized laboratories. Our first case showed no specific antibodies to Zika virus after three days, but Zika seroconversion after eleven days and no antibodies to other flaviviruses or Chikungunya (Table 2) [3].

Way out of the critical situation

Since Zika virus is also known to be excreted in urine and semen, more precise diagnostic methods may open up for the future. Initial studies show promising results (not yet published). However, ZIKV PCR from urine and serum is already routine diagnostics in some laboratories (Fig. 1).

Pregnancy

Until now, if a pregnancy is desired after a stay in a zika area, contraception should still be used for six months to be on the safe side. For couples planning a pregnancy or pregnant women who have been in a potential cicada area in the past six months, the question often arises as to whether there may have been an undetected or even manifest cicada infection. More specific Zika assays for serotyping have been possible for about eight months. These are very important especially in case of negative PCR results in subacute or later stages because they allow diagnosis. The more specific tests are still very new. In the coming months, however, cicada diagnostics are very likely to become much more accurate.

Critical interpretation of the data

In view of the not entirely trivial interpretation of Zika diagnostics, the published numbers of Zika cases from the various regions of the world make one sit up and take notice. Were only IgG antibodies measured or was the virus detected? Specific Zika antibodies could not even be routinely detected at the time of the major Zika epidemics. Due to the lack of antigen testing in developing countries (as well as in some developed countries), questions will likely remain unanswered for some time. In addition, there is the current situation in Brazil: According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, cases of yellow fever resulting in death have already occurred in seven states this year. Patients initially present with fever, headache and aching limbs, similar to Zika. Since flaviviruses are also involved, the possibility of differentiation would be particularly important today. There is also the question of whether the major Zika epidemic was in fact always a case of Zika.

Take-Home Messages

- Zika virus was first isolated from a rhesus monkey in Uganda 70 years ago. It is an RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus.

- The most important reason why Zika is of concern to the world public is its association with neonatal microcephaly.

- The interpretation of Zika diagnostics is not trivial. Zika virus has a very short viraemic period. IgM and IgG antibodies are measured. However, due to cross-reactivity, interpolation of Zika IgM/IgG antibodies is difficult and often misleading. In addition, dengue and other flaviviruses such as TBE, West Nile to yellow fever lead to false positive results.

- Because Zika virus is also shed in urine and semen, opportunities for more precise diagnostic procedures are opening up.

Acknowledgments: For review of the manuscript and personal communication during its preparation, the authors would like to thank M. Dobec, MD, medica, Medical Laboratories Dr. F. Käppeli, Zurich.

Literature:

- Ministério da Saúde, Brazil: Portal da Saúde Nota à Imprensa Confirmação do Zika Vírus no Brasil. In Portuguese. [Accessed 19 May 2015].

- Zanluca C, et al: First report of autochthonous transmission of Zika virus in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2015 Jun; 110(4): 569-572.

- Gyurech D, et al: False positive dengue NS1 antigen test in a traveler with an acute Zika virus infection imported into Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 2016; 146: w14296.

- Dick GWA, Kitchen SF, Haddow AJ: Zika virus. I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1952; 46: 509-520.

- Hayes EB: Zika virus outside Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15: 1347-1350.

- Pierson TC, et al. (Ed.): Fields virology. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia 2013; 747-794.

- Wong PS, et al: Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse): a potential vector of Zika virus in Singapore. PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7(8): e2348.

- Tappe D, et al: Acute Zika virus infection after travel to Malaysian Borneo, September 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21(5): 911-913.

- Lanciotti RS, et al: Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14(8): 1232-1239.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(6): 34-37