Life expectancy and quality of life of ALS patients can be improved with modern therapy. The patient’s will is paramount and must always be determined. There is no news on drug therapy – riluzole should be started early. At the beginning of the disease, a detailed assessment in the inpatient setting of a neurological clinic is useful. Continued treatment in specialized centers during the course of the disease is recommended.

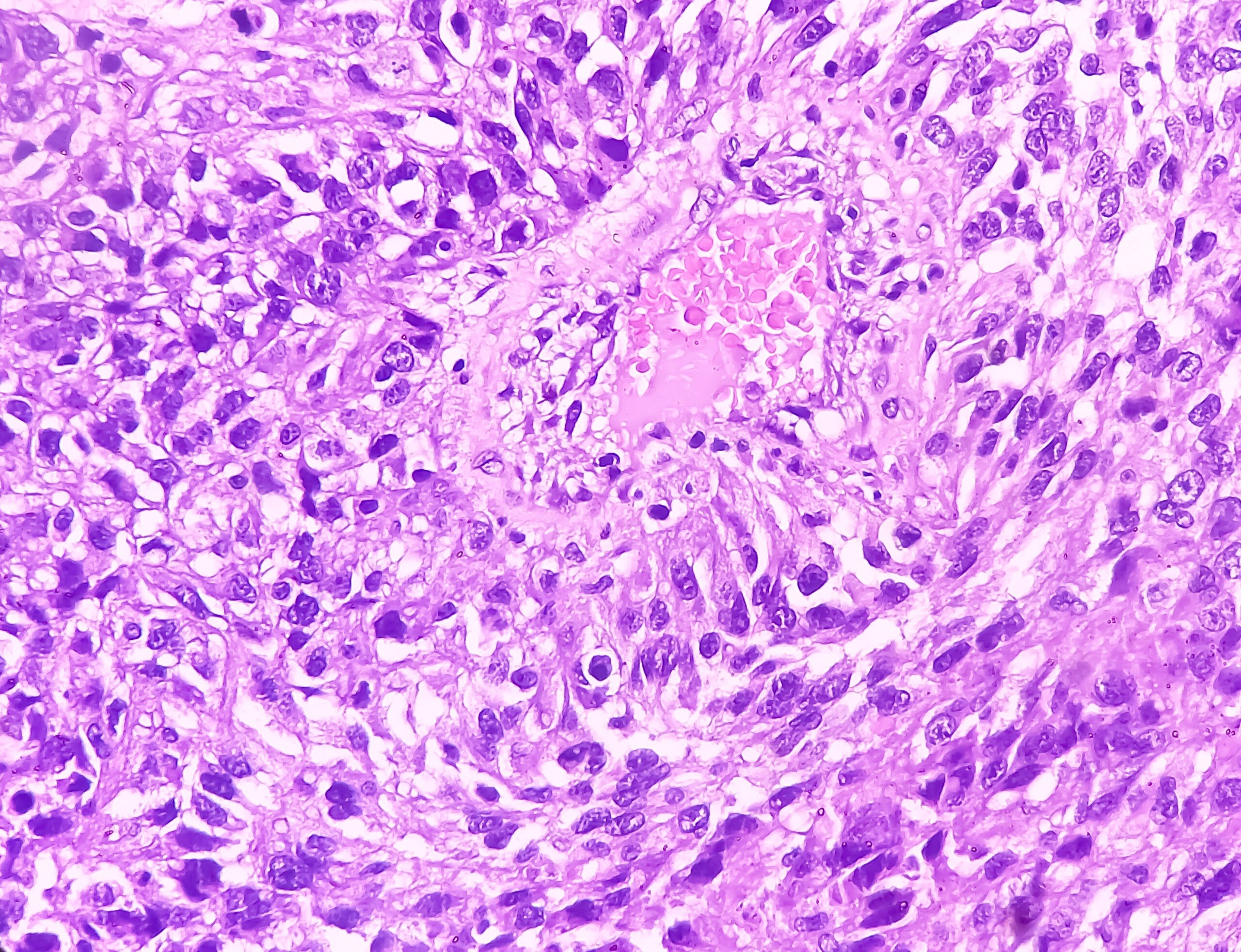

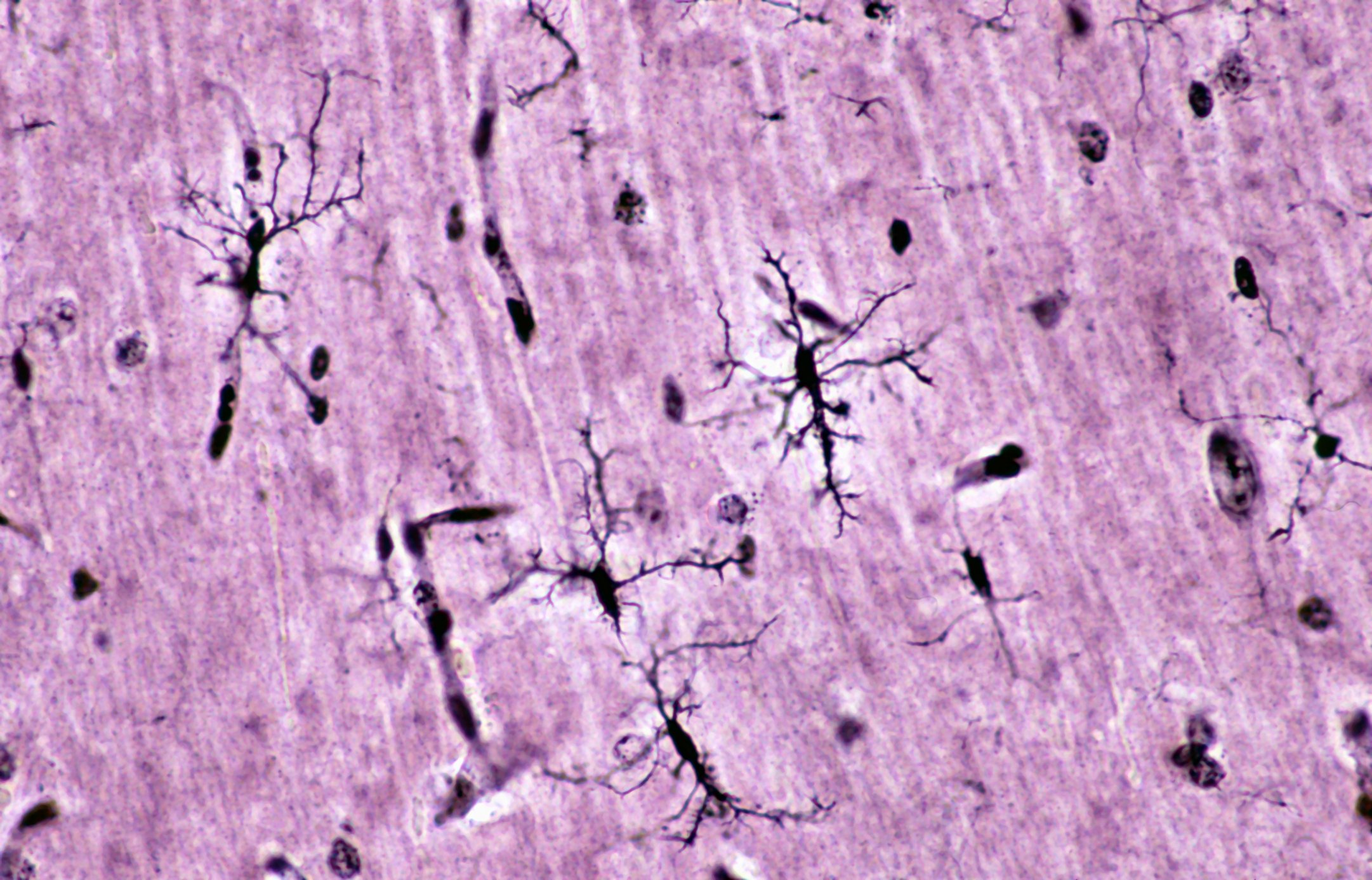

In amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the most common motor neuron disease, there is a progressive loss of nerve cells in the motor system. This typically affects both the first motoneurons of the pyramidal tract and the second motoneurons of the anterior horn cells. At the same time, the degree of expression may vary, especially at the beginning of the disease, and the signs of the first or the second motoneuron may dominate in each case. The spectrum of motor neuron diseases includes other diseases such as primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) or spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), which in turn only affect the first or second limb. second motor neuron.

The incidence of ALS is rare compared to other diseases. However, the incidence is still around 2/100,000 inhabitants, which is only slightly lower than the incidence of multiple sclerosis, for example. In contrast, the prevalence is very low at 3-8/100,000 inhabitants [1]. This indirectly reflects the short average survival of patients after diagnosis, which in the majority of cases is only two to four years. Interestingly, however, about 10% of patients have a much slower course with survival over ten years.

Modern and maximum supportive therapy can now significantly prolong the survival of patients with the disease and improve their quality of life, at least with regard to essential symptoms such as pain, hunger and shortness of breath. However, especially in the light of improved medical possibilities, it is very important to always put the wishes of the affected person at the center of therapeutic decisions [2]. For this purpose, a detailed living will should be drawn up at an early stage, which must be reviewed again and again as the disease progresses.

Principles of diagnostics

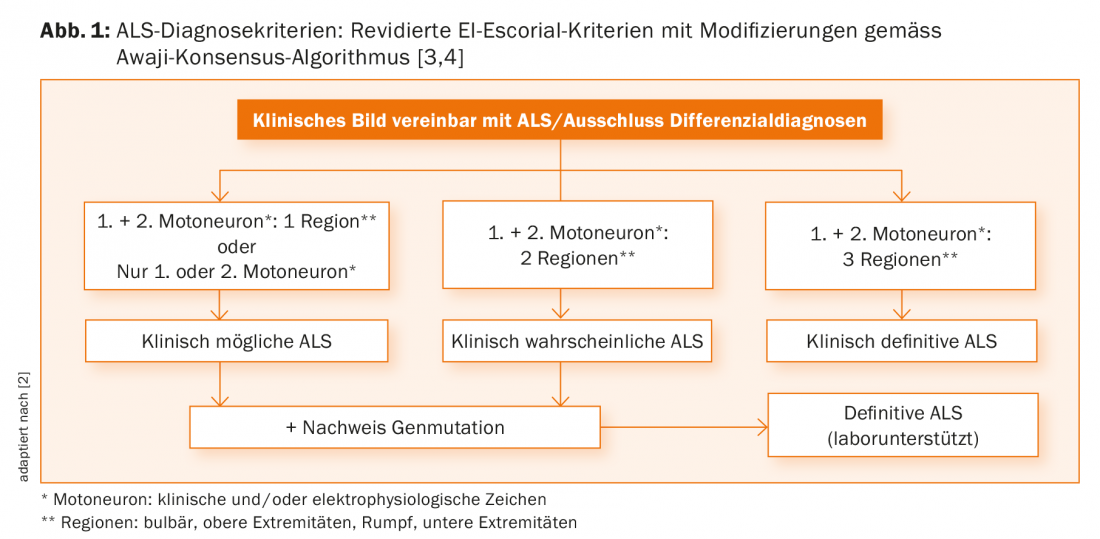

The cornerstones of diagnosis in ALS continue to be history taking and clinical examination. When these are performed by an experienced neurologist, there is usually already clear evidence of the presence of progressive damage to the first and/or second motor neuron. This alone can already diagnose probable or definite ALS according to the valid diagnostic criteria [3]. Clinical findings can be further corroborated by electrophysiologic findings, which are now increasingly incorporated into the diagnostic algorithm (Fig. 1) [4].

Unfortunately, with the current criteria, a definite diagnosis can often only be made late in the course of the disease, which on the one hand can unsettle referring physicians, patients and relatives, and on the other hand does not provide a good basis for scientific studies. Therefore, the revision of diagnostic criteria continues to be of great importance.

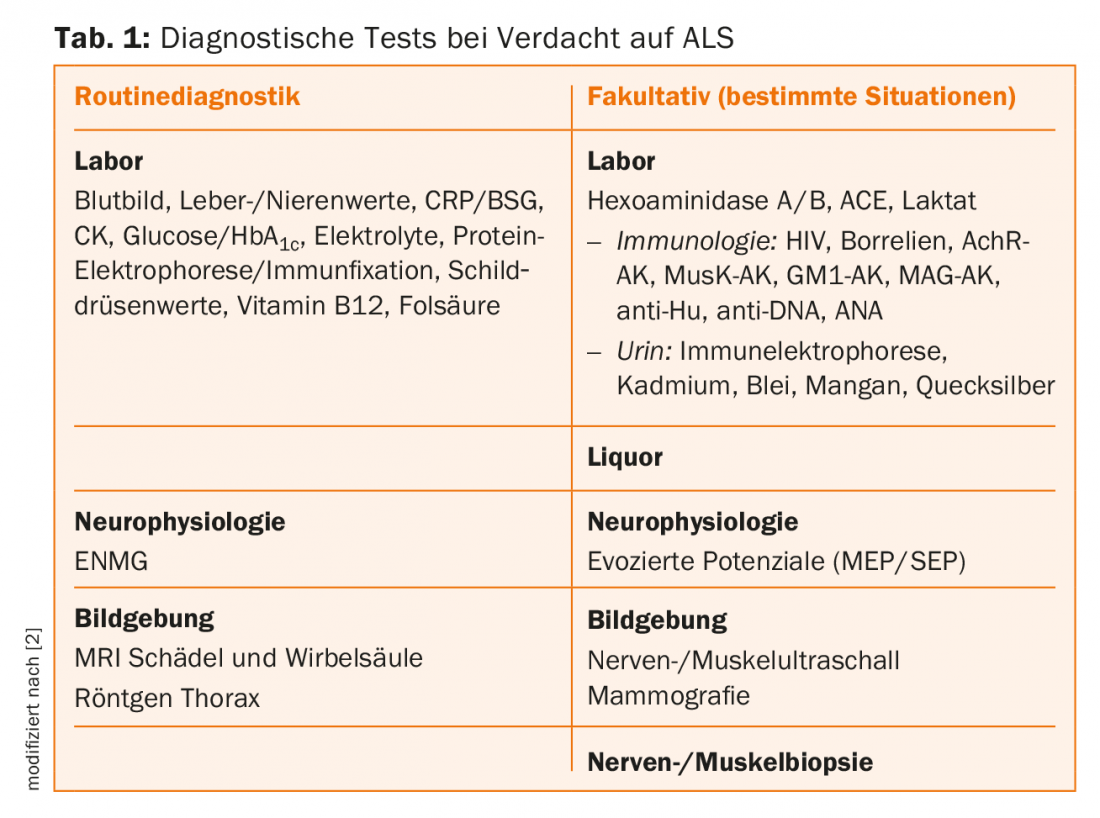

An essential diagnostic task is to rule out any differential diagnoses that may produce a similar constellation of symptoms. These are clearly summarized in the current EFNS guidelines [2]. As an example, the not-so-rare combination of cervical spinal stenosis and polyneuropathy may well provide the combination of first and second motor neuron signs required for the diagnosis of ALS. An inpatient evaluation in a neurology clinic at the onset of the disease has been shown to be beneficial to allow sufficient space and time for clinical assessment, exclusion of differential diagnoses, and empathic communication of the diagnosis.

Clinical examination

The initial purpose of the clinical examination is to look for signs of damage to the first and second motoneurons in the four body regions (bulbar, upper extremities, trunk, lower extremities). In this context, signs of the first motoneuron include spasticity, clonia, hyperreflexia, and central disinhibition phenomena. Clinical signs of the second motoneuron are primarily fasciculations and atrophies. In addition, atypical signs should be sought in the clinical examination.

E.g., involvement of eye muscles or even lack of progression direct the attention to alternative diagnoses. Sensory disturbances, on the other hand, do not completely exclude ALS, but they too must certainly be the occasion for an intensive clarification of differential diagnoses.

Electrophysiology

Electroneurography (ENG) can be used to rule out polyneuropathy. In electromyography (EMG), a constellation of symptoms consisting of acute, subacute, and possibly chronic signs of damage is typical of ALS, reflecting the course of the disease and the preserved ability of peripheral axons to regenerate. Special attention is paid to the stability and size of motor units in single potential analysis in addition to the search for pathological spontaneous activity on the resting muscle. A matching pathological finding on EMG is an essential part of the diagnosis of ALS and may be considered equal to a clinical sign according to the modified diagnostic criteria [4].

Motor evoked potentials can detect subclinical damage to the pyramidal tract. Quantification methods of motor units (motor unit number estimation) can be described as rather scientific methods. These methods may become increasingly important, especially for disease progression and thus for clinical trials [5].

Imaging

The importance of ultrasound in the diagnosis of ALS has been increasing in recent years, although the method is not expected to reach the importance as in peripheral nerve diseases. Nerve ultrasonography can be particularly helpful in ruling out relevant differential diagnoses such as immune-mediated neuropathies. In particular, however, muscles can also be examined by means of ultrasound. For the detection of fasciculations, muscle ultrasound with its excellent sensitivity and somewhat lower specificity may in the future at least partially replace electromyography, especially in follow-up examinations [6]. Magnetic resonance imaging is primarily important in ruling out differential diagnoses. In most cases, imaging of the brain and entire spine is performed. In addition, muscles and peripheral nerves can also be imaged, although the focus here is currently still more in the scientific field than in clinical practice.

lies.

Genetic diagnostics

Genetic diagnostics in ALS has been extended by several aspects in recent years. Over many years, mutations in the Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene SOD1 in particular have been sought, which are responsible for about 10-15% of familial ALS cases. Thereby, paradoxically, there are families in which the detection of the mutation does not correlate with the occurrence of the disease, indicating that other disease-causing factors or genes must exist [7]. In the meantime, an essential new gene locus has been found in this regard with the gene C9orf72. Mutations in this gene are responsible for about 25% of familial cases and about 10% of sporadic cases. Interestingly, mutations in this gene also exist in a similar proportion of cases of fronto-temporal dementia, highlighting the link between the two diseases at the genetic level as well [8].

Genetic tests of the most common mutations are commercially available today. It must be emphasized all the more that genetic diagnostics belong in experienced hands, especially in ALS. It should only be ordered after detailed examination and consultation with neurologists and human geneticists familiar with the disease, as the result may have great relevance, especially for counseling asymptomatic family members.

Further diagnostics

If cognitive abnormalities are suspected, neuropsychological testing is recommended. Depending on the duration of the disease, up to 50% of ALS patients develop dysexecutive symptoms, and in about 15% a diagnosis of fronto-temporal dementia can be made. This observation contradicts previous doctrines that did not see cognitive impairment in ALS. Moreover, patients with fronto-temporal dementia should also be thoroughly examined for signs of motor neuron disease, which also occurs frequently during the course of the disease. Otherwise, further diagnostics essentially serve to exclude differential diagnoses [2].

Drug therapy

Furthermore, riluzole is the only approved drug for the treatment of ALS, and a prescription as early as possible in the course of the disease is recommended. The medication is safe; in addition to mild fatigue, elevation of liver enzymes rarely occurs. The course of the disease can be slowed somewhat with riluzole. In addition, other symptom-oriented drug therapies may be used, such as amitriptyline or atropine drops for troublesome salivation. Potentially sedating drugs such as benzodiazepines and opiates can be used very well to treat anxiety, pain, and dyspnea, subject to relatively narrow therapeutic limits.

Nutrition

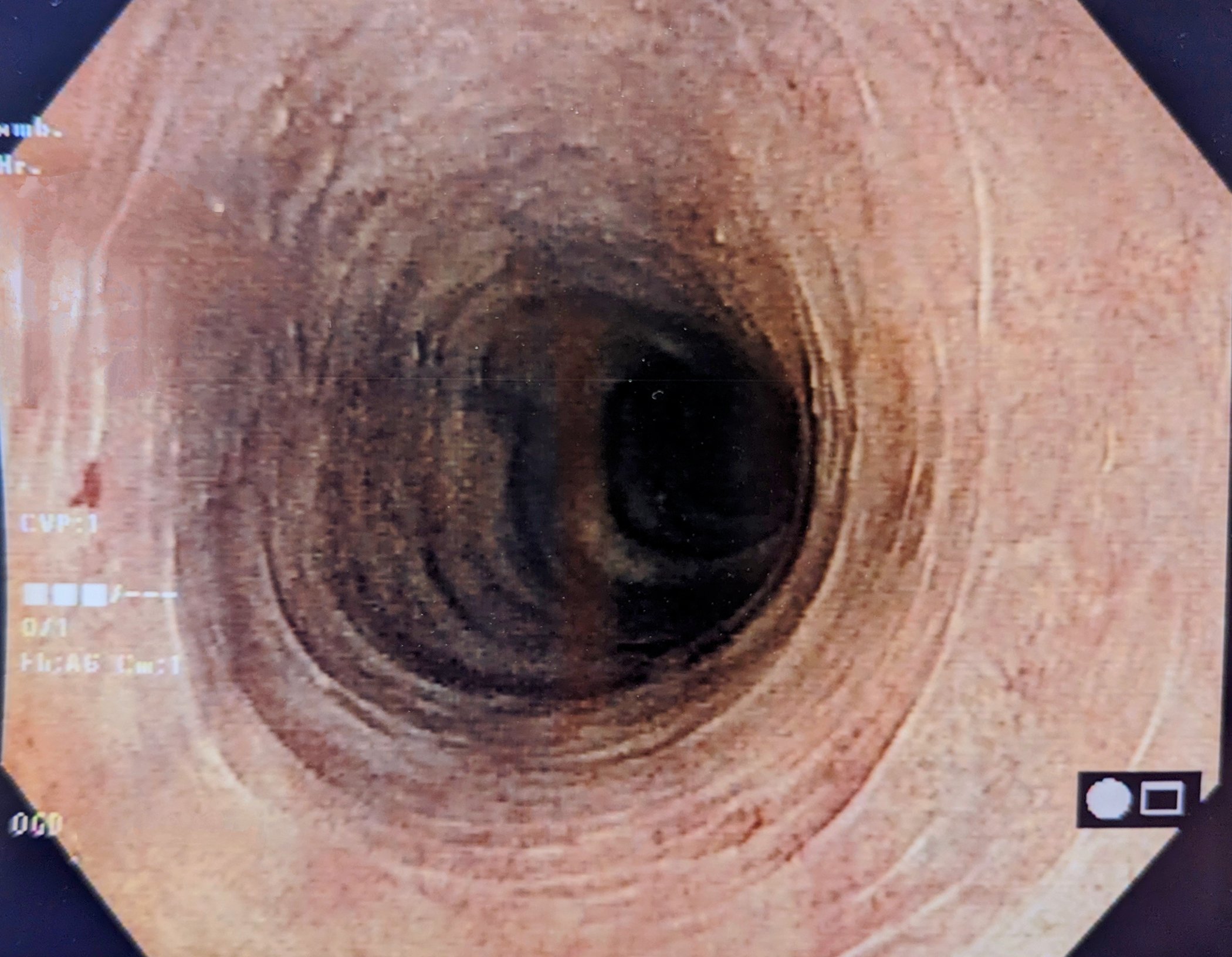

Weight loss represents a negative prognostic marker that should be avoided if possible. The patients and their relatives can be advised accordingly and nutritional supplements can be offered. Close logopedic monitoring for early detection of dysphagia is of great importance so that the offer of percutaneous enteral nutrition by means of a PEG tube can be made as early as possible. The earlier in the course of the disease a PEG is placed, the lower the risk of complications and the more likely the measure can contribute to an improvement in quality of life and survival. What is important for those affected is the fact that additional oral food intake remains possible as a matter of course.

Ventilation

At any time during the course of the disease, watch for symptoms of hypoventilation, especially at night. In addition to dyspnea, these include daytime sleepiness, morning headache, or orthopnea. These symptoms can be treated very effectively with non-invasive home ventilation, which significantly improves the quality of life of those affected. This effective symptomatic treatment should be discussed with all affected persons at an early stage when corresponding symptoms occur, since it can improve the quality of life of the affected persons, at least for a limited time, like hardly any other therapy [9]. Invasive ventilation, on the other hand, is only considered for a select group of patients. If at some point during the course of the disease the patient wishes to discontinue ventilation, this must be respected and accompanied accordingly. Usually, this measure soon leads toCO2 retention, and patients die in slow-onsetCO2 anesthesia.

Other therapy

Very essential for the optimal care of ALS patients is a close-meshed specialized and multiprofessional treatment, such as that provided in an ALS center or comparable institutions. On the one hand, the aforementioned therapies can be applied at an early stage and optimally coordinated, and on the other hand, other therapeutic measures such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy can be usefully supplemented, the aim of which is to preserve functions that are still intact, such as the ability to communicate, for as long as possible.

Literature:

- Schweikert K: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Swiss Medical Forum 2015; 15: 1068-1073.

- Andersen PM, et al: EFNS guidelines on the clinical management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MALS) – revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19: 360-375.

- Brooks BR, et al: El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2000; 1: 293-299.

- Carvalho MD, et al: Awaji diagnostic algorithm increases sensitivity of El Escorial criteria for ALS diagnosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009; 10: 53-57.

- Schulte-Mattler WJ, et al: MUNIX – a promising biomarker in ALS. Clin Neurophysiol 2015; 46: 186-189.

- Schreiber S, et al: Experience status and significance of imaging methods in ALS-induced neuromuscular changes. Clin Neurophysiol 2016; 46: 173-181.

- Felbecker A, et al: Four familial ALS pedigrees discordant for two SOD1 mutations: are all SOD1 mutations pathogenic? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010; 81: 572-577.

- Rohrer JD, et al: C9orf72 expansions in frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 291-301.

- Boentert M, et al: Ventilation and secretion management in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neurophysiol 2015; 46: 163-172.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(2): 26-29.