What should be considered regarding diagnosis and treatment of pituitary adenomas? To what extent is a distinction between hormone-secreting and hormone-inactive incidentalomas relevant to treatment? The endocrinology session at this year’s Medidays provided information on important aspects of the workup of pituitary adenomas.

Incidentalomas are lesions found incidentally during imaging studies for other diseases or nonspecific symptoms (e.g., headache). The prevalence of incidentalomas of the pituitary gland varies depending on study data (CT, MRI, autopsy) and is in the range of 4-40%, with the majority being less than 10 mm in size, Dr. Tschopp said. The vast majority of incident pituitary tumors are adenomas, benign tumors of the parenchymatous cells of the anterior lobe of the pituitary [1]. However, the speaker emphasized that the differential diagnosis is very broad and that collaboration between endocrinologists and neuroradiologists is important. The etiology included other neoplasms (e.g., craniopharyngeomas, germinomas, metastases or lymphomas, very rarely carcinomas), inflammatory/granulomatous diseases (neurosarciodosis, histiocytosis, abscess, hypophysitis), and cystic changes (Rathke’s cysts, colloid cysts).

Clinical guidelines

According to clinical guidelines, in addition to targeted sellar imaging, the following workup should be performed in all patients with incidentaloma of the pituitary gland (including those without symptoms) [2]:

- Clinical examination and laboratory test regarding hormonal hypofunction (hypopituitarism).

- Clinical examination and laboratory testing regarding hormonal hyperfunction (hormone hypersecretion).

Diagnosis should be guided by the following three guiding questions:

a) Is there a mass effect?

(Headache, visual field loss due to compression of the optic chiasm or double vision?)

b) Is there evidence for pituitary insufficiency?

(Anterior lobe insufficiency and/or diabetes insipidus?)

c) Is it a hormone-secreting adenoma?

(Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly or hyperprolactinemia?)

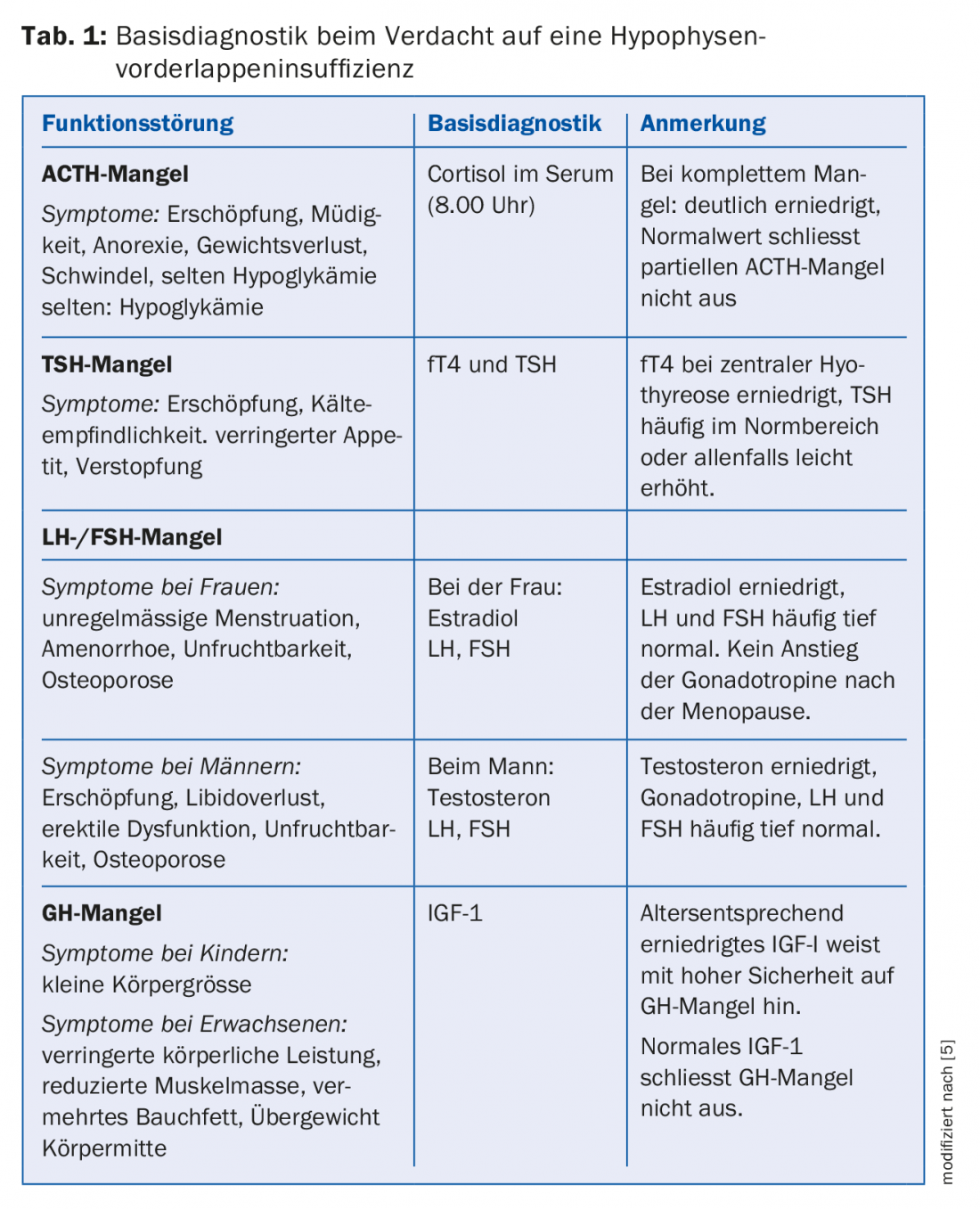

Is there evidence for pituitary insufficiency?

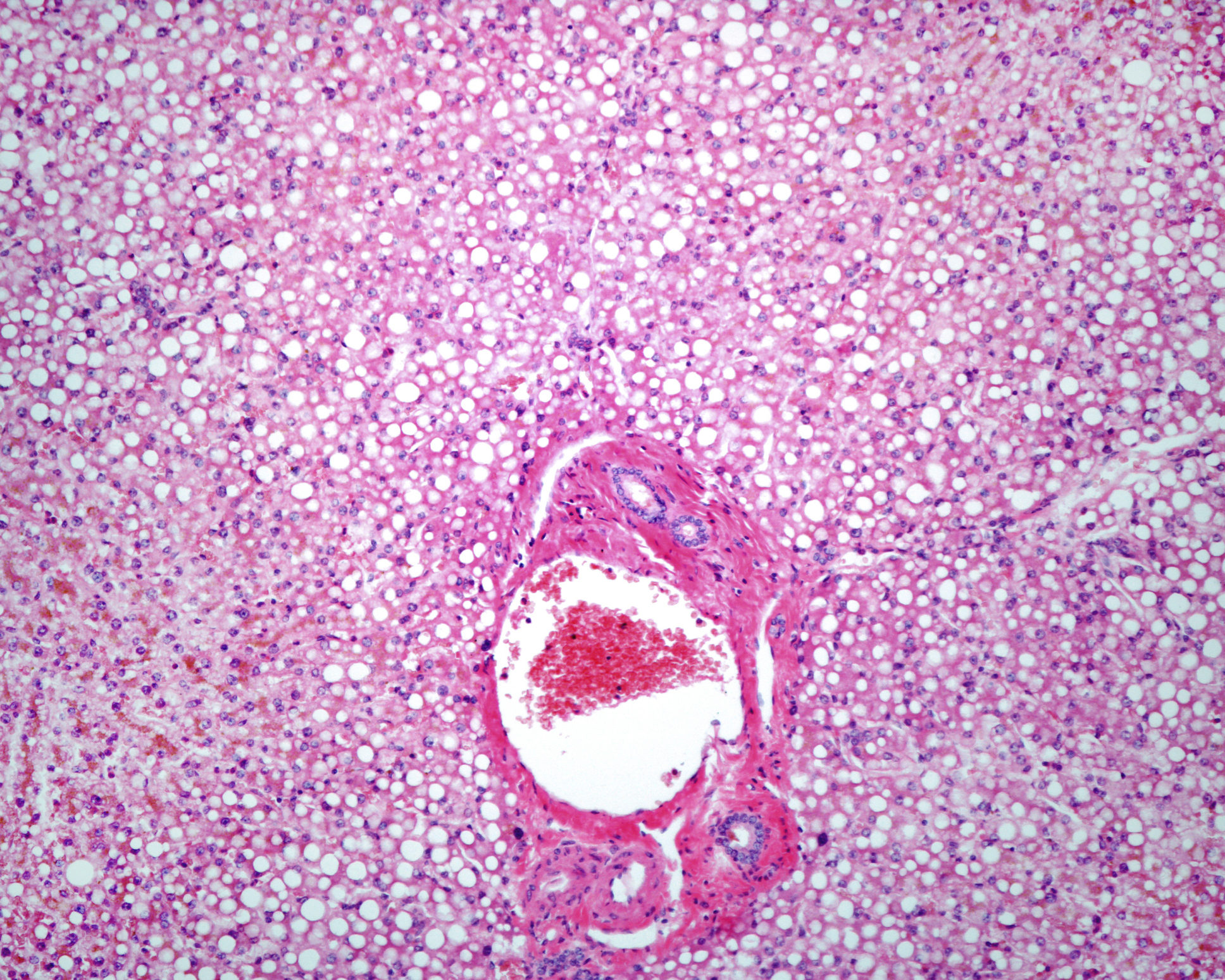

Symptoms of pituitary insufficiency are often nonspecific (e.g., fatigue, decreased performance, etc.) and sometimes occur insidiously over months or years (Table 1). Pituitary adenomas are the most common cause of pituitary insufficiency, although this is especially true for macroadenomas [5]. If pituitary insufficiency is suspected, peripheral hormones (cortisol, fT4, testosterone/estradiol, IGF1) should be measured for extended diagnosis. Determining only the pituitary hormones (ACTH, TSH, LH/FSH, GH) is unreliable because they are often within the normal range (“inadequate-normal”) and suggest an intact hormonal axis, Dr. Tschopp said. If pituitary hyper- or hypofunction due to a pituitary adenoma is suspected, the following baseline parameters can be determined: *cortisol, GH, *IGF-1, TSH, *fT4, LH/FSH, *testosterone/estradiol, and prolactin [1] (*according to the speaker, the most important hormones for the diagnosis of insufficiency).

Blood samples for diagnosis should be taken in the early morning, as cortisol and testosterone in particular are subject to strong circadian rhythms. If the findings are inconclusive, further tests may be required, which are usually performed by a specialist in endocrinology [5]. It was specifically pointed out that the measurement of cortisol in the morning is an appropriate parameter in adrenal insufficiency, but has no reliable significance with regard to hyperfunction (Cushing’s disease); there are strong overlapping values in healthy individuals and patients. It should also be noted that diabetes insipidus with polyuria/dipsia is not a typical finding in pituitary adenomas, rather this should direct the differential diagnostic workup in another direction (craniopharyngeoma, germinoma, granulomatous disease).

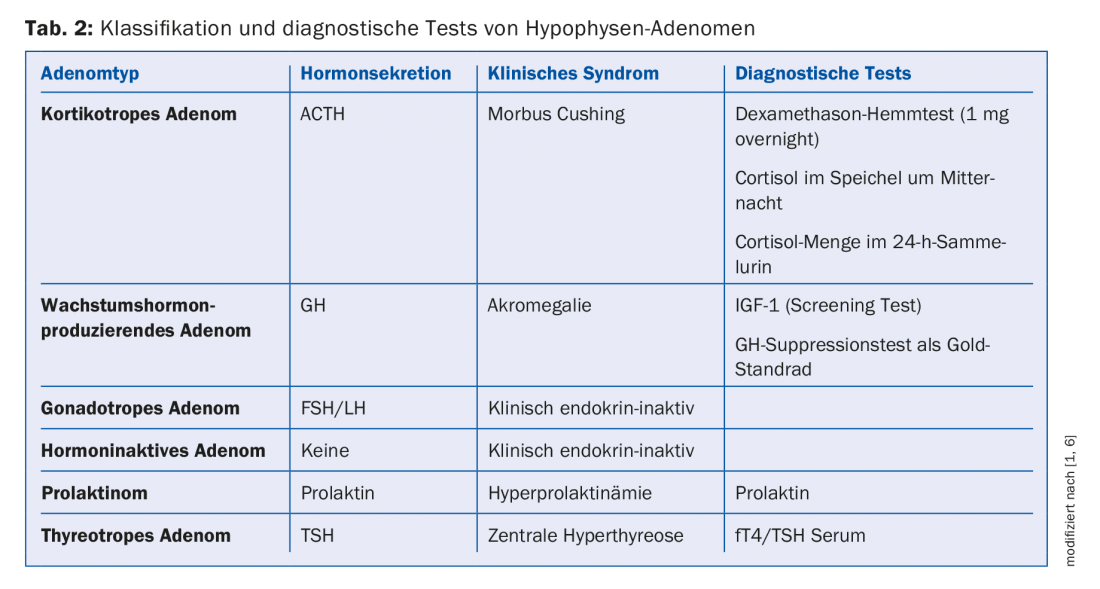

Is it a hormone-secreting adenoma?

Prolactin and IGF-1 are meaningful parameters in the diagnosis of hyperfunction. If prolactin levels are normal, prolactinoma can be ruled out. If IGF levels are not elevated, acromegaly can be excluded with high probability.

Cushing’s disease: For the diagnosis of Cushing’s disease, further examinations are necessary: In addition to the determination of the amount of cortisol in the 24h collection urine, the circadian rhythm can be examined by measuring the cortisol in saliva at midnight or the regulation of cortisol self-production can be checked (dexamethasone suppression test, 1 mg overnight). It should be taken into account that elevated cortisol levels and pathological test results can be found in the context of other diseases (e.g., pseudo-Cushing’s in alcohol dependence, depression, hyperglycemia, stress, infection). It is important to note that elevated basal cortisol levels are not evidence of the presence of Cushing’s syndrome, and in the case of normal basal cortisol levels, Cushing’s syndrome cannot be ruled out. In patients who are first clinically suspected of having Cushing’s syndrome, the above diagnostics should be performed primarily and hyperphysiologic imaging should be sought only if the excess is confirmed.

Acromegaly: Acromegaly is also a rare disease. Clinical features of acromegaly include (incomplete): altered facial features, enlargement of the hands and feet, sleep apnea syndrome, arthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, hyperhidrosis, high blood pressure and blood sugar. Due to the slow progression of the disease, acromegaly is often diagnosed after a period of about ten years and, according to the speaker, can lead to a significant reduction in life expectancy. In patients with typical clinical features of acromegaly, it is recommended to determine IGF-1 levels as screening. In patients with incidentaloma, measurement of IGF-1 levels is also recommended to reliably exclude acromegaly in oligosymptomatic patients. If there is strong evidence of acromegaly, the suspected diagnosis can be confirmed by a GH suppression test (oral glucose tolerance test with 75 g glucose).

Prolactinemia: Prolactinomas are relatively common and account for about 30-40% of all pituitary adenomas. Prolactinomas represent a special case of pituitary adenomas, since prolactinomas can usually be very well treated with medication (dopamine receptor agonists, e.g. cabergoline). It was emphasized that an elevated prolactin level in an incidentaloma is not automatically indicative of a prolactinoma; differential diagnosis should be thought of disinhibition hyperprolactinemia (pedicle compression in microadenoma). Medications are an important cause of hyperprolactinemia, and a careful history is essential in this regard. Elevated prolactin levels are occasionally found with the following medications; antipsychotic medications, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), medications used to treat nausea and gastric motility disorders. An incomplete medication history resp. Non-reporting by the patient often leads to findings of unclear and transient hyperprolactinemia. It is recommended that a baseline determination of prolactin be performed before starting therapy with antipsychotic medications, as this value can help to narrow down the cause and avoid unnecessary investigations during the course.

Due to the complexity of the disease, interdisciplinary care of patients by neurosurgeons, neuroradiologists, endocrinologists, ophthalmologists, and radiation oncologists in a center with a high number of cases is recommended. For this purpose, the University Hospital Zurich offers colleagues in private practice the opportunity to present their own cases at the Interdisciplinary Pituitary Board.

Source: Medidays, September 3-6, 2018, Zurich

Literature:

- Maldaner N, et al: Modern Management of Pituitary Adenomas-Current State of Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up. Praxis 2018; 107(15): 825-835. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a003035.

- Freda PU, et al. : Pituitary incidentaloma : an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011 ; 96(4) : 894-904. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1048.

- Molitch ME: Nonfunctioning pituitary tumors and pituitary incidentalomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2008; 37: 151-171.

- Molitch ME: Pituitary tumors: pituitary incidentalomas. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 23: 667-675.

- Möller-Goede DL, Sze L, Schmid C: Hypopituitarism. Swiss Med Forum 2014; 14(49): 927-931.

- Lake MG, Krook LS, Cruz SV: Pituitary adenomas: an overview. Am Fam Physician 2013; 88: 319-327.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(9): 42-44