Fall and fracture prevention are particularly important in the elderly, as such injuries can contribute not insignificantly to increased morbidity and concomitant loss of autonomy. To prevent falls and fractures, the causes must be understood and treated. A review of the contribution of vitamin D and calcium supplementation to this problem.

If the clumsy fall of a toddler is still perceived as cute and harmless, the assessment of a fall changes with increasing age. Especially in seniors, the risk of accompanying bone fractures in falls always resonates. A study by Melton et al. was able to prove that 75% of all vertebral body, radius, and hip fractures occur in the age group of ≥65 years [1]. The frequency with which older people fall in everyday life should also not be underestimated. 30% of all >65-year-olds and 50% of all >80-year-olds fall at least 1×/year [2]. In addition to some exogenous factors, such as trip hazards, inadequate lighting conditions, or ill-fitting footwear, intrinsic factors also play their part in the development of falls and the increased risk of injury from falls in old age. For >65-year-olds, two key factors in the context of fall and injury risk are bone and muscle health, according to Prof. Bischoff-Ferrari, Clinic Director Geriatrics UniversitySpital Zurich, Chief Physician University Clinic for Acute Geriatrics, Waid City Hospital, and Director Center Age and Mobility, University of Zurich.

Sarcopenia, which is the age-related decrease in muscle mass and the accompanying decrease in muscle strength, increases the risk of falling; osteoporosis, which is the decrease in bone mass associated with decreased bone stability, contributes to an increased risk of bone injury. Due to the frequent presence of comorbidities and an altered healing process, a fall with subsequent fracture quickly endangers the autonomy of a senior citizen who has previously been able to care for himself independently. Last but not least, 40% of all nursing home admissions occur due to fall events and their consequences [2]. A fall can thus not only become a personal catastrophe, but also has the potential for drastic health economic consequences.

Influence of vitamin D

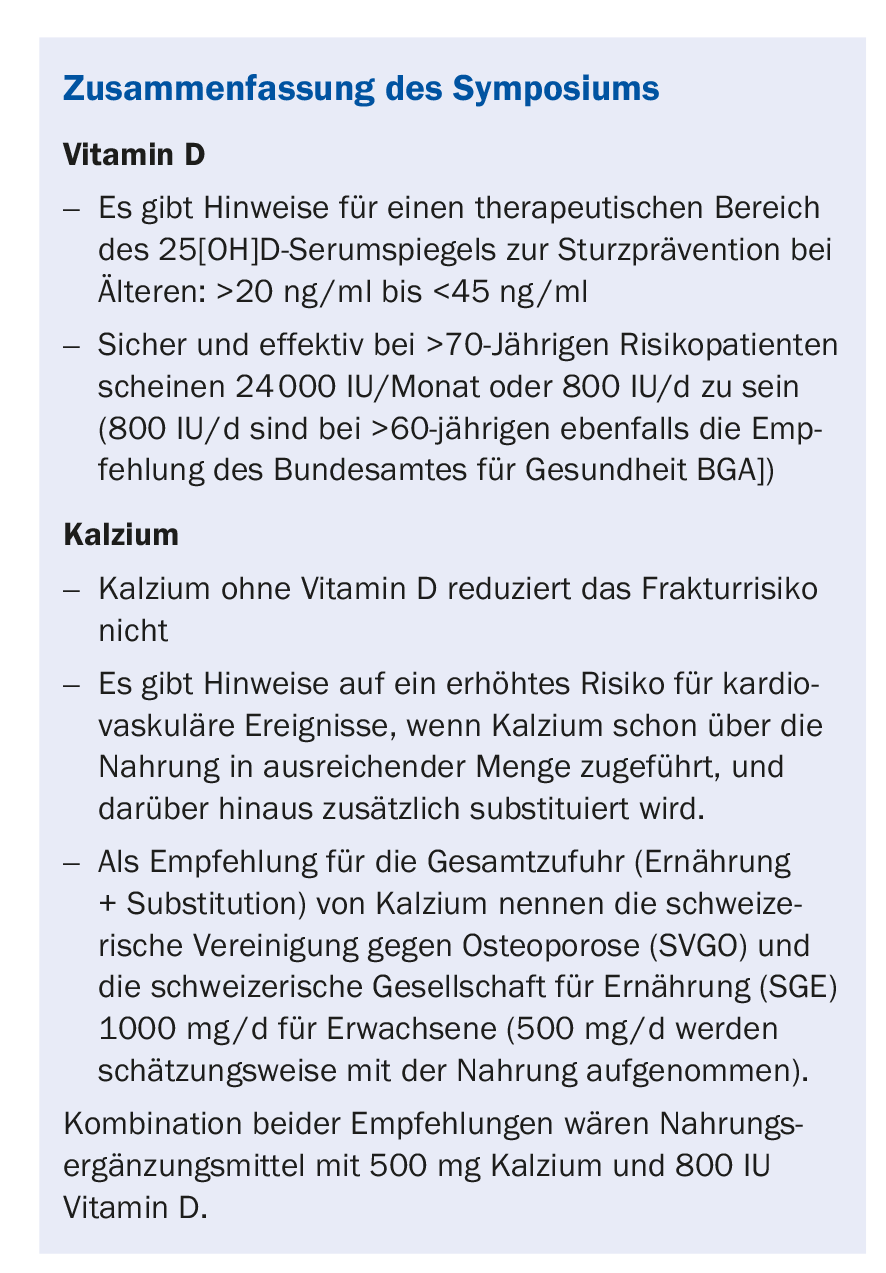

Much discussed in the context of fall and fracture prevention in old age is the role of vitamin D. Vitamin D is an important factor in maintaining bone health. It stimulates calcium absorption from the intestine and promotes bone mineralization. Among a variety of other functions, the vitamin is thought to have a direct effect on muscle via the vitamin D receptor (VDR) [3–5]. Hypovitaminosis D can lead to impaired physical functionality in daily life [6] and myopathy with muscle weakness, symptoms that can be improved by vitamin D supplementation [7]. Studies have shown that vitamin D supplementation at a dose of 700-1000 IU/d can reduce the risk of falls in the elderly by 19% [8]; vitamin D administration of approximately 800 IU/d (in some cases combined with calcium in the studies analyzed) can reduce the risk of hip fracture by 30% in ≥65-year-olds [9].

Vitamin D supply

Humans are able to produce the majority of the required vitamin D endogenously with the help of sunlight (UVB radiation), in addition, the vitamin is also found in a small number of foods (fatty fish, liver, egg yolk, some types of mushrooms) and can be supplied externally. Serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D), the precursor of biologically active vitamin D, are determined to verify adequate supply of the vitamin. A deficiency is present at a value <20 ng/ml.

In order to cover the need for vitamin D through food, it would take, for example, the twice-daily intake of fatty fish such as herring, salmon or sardines, or 12-14 eggs per day, according to Prof. Bischoff-Ferrari. However, the sole supply via endogenous provision of vitamin D has limiting factors. In northern European latitudes, there is a risk that the irradiance and angle of incidence of the sun’s rays in the months of November to May are not optimal for stimulating sufficient production of vitamin D in the skin. In addition, the carcinogenic effect of UV radiation leads to sunlight exposure of insufficiently large areas of skin or the use of high SPF sunscreens, two measures recommended for prophylaxis of skin cancer, but which impede endogenous production of sufficient vitamin D. The elderly population is particularly at risk for developing hypovitaminosis-D. Older people tend to have less exposure to sunlight, and the skin’s ability to produce vitamin D also decreases with age [10]. All these factors result in about 50% of healthy people aged ≥65 years and 80% of all elderly people with hip fracture having vitamin D deficiency [11].

The more the better?

Thus, if exogenous intake via food and endogenous endogenous production are insufficient to meet vitamin D requirements, dietary supplements can fill the gap. Different dosage forms and dosages exist. As mentioned above, a preventive effect with regard to falls was found for certain dosages. So would higher doses of vitamin D prevent even more falls in the elderly, and how safe is this approach? This question is also interesting with regard to a monthly dosage, as this is highly practical for elderly patients due to their usually limited mobility. In her presentation, Prof. Bischoff-Ferrari reported on a clinical study from Zurich in which different vitamin D doses were compared.

Zurich Disability Prevention Trial

In the Zurich Disability Prevention Trial [12], a double-blind, randomized clinical trial, 200 Swiss women and men ≥70 years living independently at home were assigned to three different intervention groups. In the year prior to study entry, 100% of participants had fallen at least once. Vitamin D was given at different monthly doses: 24 000 IU/month, 60 000 IU/month, or 24 000 IU/month plus 300 µg calcifediol/month. The primary endpoint was improved lower extremity function and 25[OH]D serum levels of at least 30 ng/ml at six and 12 months. Secondary endpoint was the number of fall events per month.

Pre-existing vitamin D deficiency was resolved after 12 months of study in all groups. It was found that the higher doses of vitamin D (60,000 IU and 24,000 plus calcifediol) were more effective in achieving the established threshold of 30 ng/ml 25[OH]D. Leg function also improved in all three groups compared with baseline values, but there was no significant difference between groups. Overall, 61% of patients fell during the 12-month study period. In the group with a monthly dosage of 24,000 IU vitamin D, this was 48% of the group members, compared to 67% with 60,000 IU and 66% with 24,000 IU combined with calcifediol (p=0.048). In terms of the 25[OH]D serum levels, the range of 21.3-30.3 ng/ml showed the fewest falls; this level was most achievable with monthly dosing of 24 000 IU. Study participants who reached 25[OH]D serum levels of >45 ng/ml also had the greatest risk of falls. None of the patients in the 24,000 IU monthly vitamin D dosage group reached this high 25[OH]D blood level.

Based on these study results, the authors recommend 24,000 IU vitamin D monthly (equivalent to 800 IU/d) in ≥70-year-olds with a history of falls and discourage doses ≥60,000 IU/month (equivalent to 2000 IU/d) in this patient group.

And calcium?

The calcium found in the human body is present to approx. 99% in bound form in bones and teeth and gives these structures stability through calcium-rich compounds. In addition, calcium has a number of other functions in the organism, among others it is involved in muscle contraction as well as blood clotting. Due to its stabilizing function on the bone, an adequate supply of calcium in old age is considered important, especially with regard to the prevention of osteoporosis and bone fractures. In Switzerland, the Swiss Association against Osteoporosis (SVGO) and the Swiss Society for Nutrition (SGE) recommend a total intake of 1000 mg of calcium per day for adults, including dietary sources of calcium and any additional substitutions. In practice, calcium supplementation is increasingly performed in combination with vitamin D administration, with the aim of achieving a synergistic effect in terms of bone health. This combination is already practiced, for example, in the form of milk supplemented with vitamin D, as sold in supermarkets in the USA.

In the symposium, Prof. Bischoff-Ferrari gave an overview of studies that investigated the effect and risks of calcium supplementation in the context of bone health.

In a meta-analysis published in 2007, it was shown that the administration of calcium alone (without vitamin D) did not result in any advantage with regard to non-vertebral fractures compared to placebo administration; with regard to hip fractures, there was even evidence of a possibly increased fracture risk [13].

In another meta-analysis, calcium supplementation of ≥500 mg/d showed an overall 31% increased risk of myocardial infarction compared with placebo, with increased risk among study participants who were already achieving adequate dietary calcium intake above 805 mg/d [14]. However, the study evidence on cardiovascular events during high-dose calcium substitution is inconclusive. The data presented by Lewis JR, et al. conducted meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed no significantly increased risk of coronary heart disease or clinical manifestations (such as e.g. myocardial infarction) or increase in all-cause mortality when taking ≥500 mg/d calcium with or without vitamin D, in this case studied in postmenopausal women [15].

Milk, as a dietary source of calcium, showed none of the risks mentioned, Prof. Bischoff-Ferrari said. According to various studies, milk neither leads to hypercalcemia nor to an increased risk of heart attack. A meta-analysis also suggested that there is a protective effect per glass of milk with respect to hip fractures, at least in men [16]. More study data would be needed to confirm this. Last but not least, dairy products are valuable nutritional ingredients because they contain high-quality protein, another important factor for bone and muscle health.

Source: 19th Continuing Education Conference of the College of Family Medicine (KHM), June 22-23, 2017, Lucerne.

Literature

- Melton LJ3rd, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM: Osteoporos Int 1999; 9(1): 29-37.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA: Primer of Metabolic Bonde Diesease9th Edition 2017-07-10

- Ratchakrit Srikuea, et al: Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2012; 303(4): C396-C405.

- Lisa Ceglia, et al: J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98(12): E1927-E1935.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: Histochem J 2001; 33(1): 19-24.

- Sohl E, et al: J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98(9): E1483-90.

- Glerup H, et al: Calcif Tissue Int 2000; 66(6): 419-424.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: BMJ 2009; 339: b3692.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: N Engl J Med 2012; 367(1): 40-49.

- MacLaughlin J, Holick MF: J Clin Invest. 1985; 76(4): 1536-1538.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: Bone 2008; 42(3): 597-602.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176(2): 175-183.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 86(6): 1780-1790.

- Bolland MJ, et al: BMJ 2010; 341: c3691.

- Lewis JR, et al: J Bone Miner Res 2015; 30(1): 165-175.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26(4): 833-839.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(8): 49-52