Every third woman and every fifth man suffers from varicose veins. A variety of treatment options now exist. Is classic variceal stripping “out”? An overview of current therapeutic options.

Varicose vein disease is the most common disease of the veins and has been known for centuries: The pricking of varicose veins was already described by Hippocrates (469-375 BC) in his writing “On Wounds and Ulcers” [1]. Today, on average, one in three women and one in five men suffer from varicose veins of the lower extremities [2]. The prevalence of symptoms and other clinical manifestations depends on the extent of reflux in the superficial truncal veins, which can be quantified duplex sonographically [3,4]. The most common complaints are tendency to swell, feeling of heavy legs, pain after standing for a long time, itching and muscle cramps. Clinically, manifestations range from small spider veins, dilated and elongated veins (varicose veins), edema and hyperpigmentation to chronic dermatofascioliposclerosis and ulceration of the lower leg (“open legs”). The severity of varicose vein disease is described internationally according to the CEAP classification (Table 1) [5].

Surgical treatment of varicose veins has undergone several technical advances in the last century. In 1907, Babcock was the first to describe the classic varicose vein surgery: stripping of the truncal veins [6]. His method, along with its later refinements, was considered the reference standard for varicose vein treatment for over a hundred years.

This article first describes the pathophysiologic basis for successful varicose vein treatment and its evolution with the advent of minimally invasive options. On this basis, it will then be determined to what extent the new methods are able to replace classic varicose vein surgery.

Pathophysiology

The veins transport deoxygenated blood back to the heart – a process that must overcome gravity in the lower extremities depending on the position. The two main mechanisms that ensure return transport against gravity are the muscle pump and the venous valves. The muscle pump drives blood flow, while healthy venous valves dictate the direction to the heart by closing distally each time and preventing backflow.

The main cause of varicose vein disease is dysfunction of the venous valves, which is usually due to weakness of the connective tissue with dilatation of the vein wall, so that the valves no longer close. In addition to a familial predisposition, hormonal influences (female gender, pregnancy), standing or sedentary work for long periods of time, increasing age, lack of exercise, obesity, and any form of drainage obstruction are considered the most important risk factors [7]. Once a primary point of insufficiency has occurred, the increasing hydrostatic pressure in the venous segment inevitably leads to distal progression of venous insufficiency. Natural perforating veins (directional connections between the superficial and deep venous systems) can ultimately create a recirculatory loop, which can lead to volume loading of the deep venous system and thus chronic deep venous insufficiency. The spontaneous course of this severe sequelae is characterized by a high complication rate. The prognosis with adequate and timely treatment of superficial varicose disease, on the other hand, is very favorable.

In the early stages of the disease (CEAP: C0-C3), conservative therapeutic approaches (e.g., vasoactive substances, compression therapy) are usually sufficient to alleviate symptoms and can then also be recommended as the sole measure. In advanced clinical stages, however (CEAP: C3-C6), additional invasive reparative measures are often necessary (e.g., sclerotherapy, classic variceal stripping, or endovenous vein ablation) to offer a sustainable solution and thus improved quality of life.

From variceal stripping to endovenous therapy alternatives

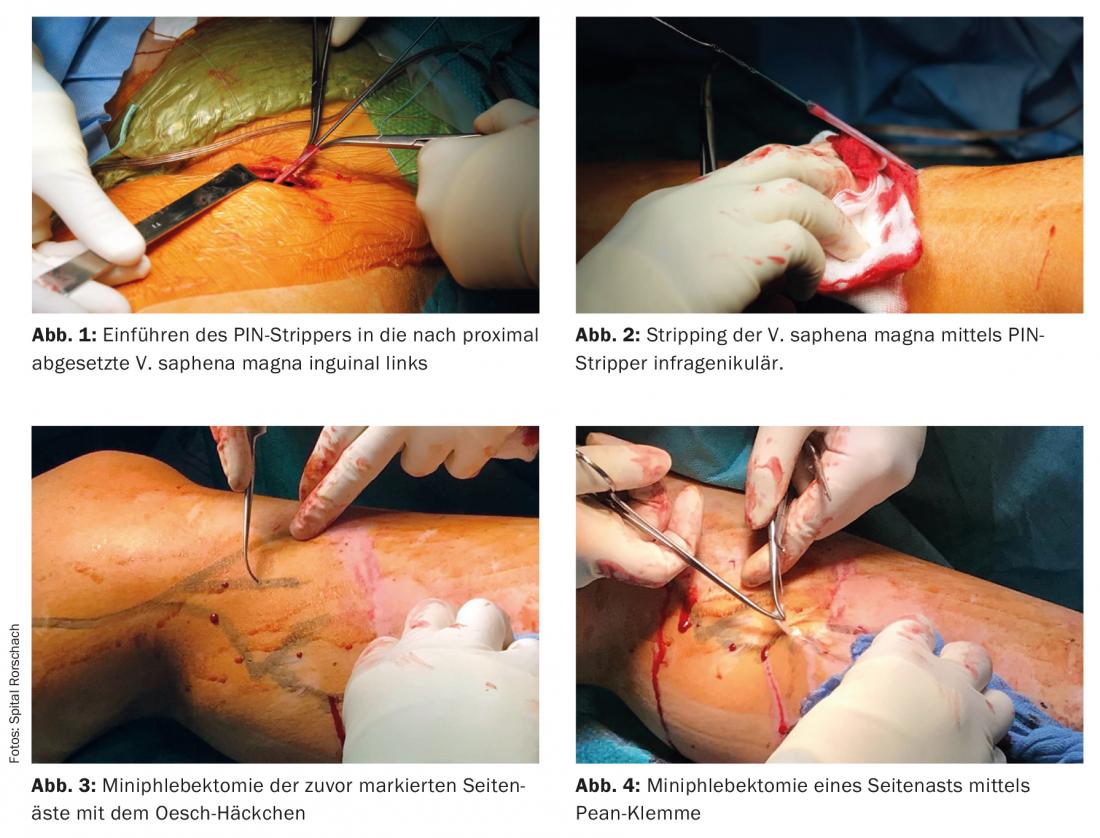

The principle of variceal stripping is the complete removal of the insufficient veins so that the backflow is interrupted. Insufficient truncal veins are exposed through small skin incisions in the groin or popliteal fossa, and separated in the area where they join the deep venous system (crossectomy, Fig. 1), probed to the distal insufficiency point and then pulled out completely (stripping, Fig. 2). Insufficient side branches are removed via additional small stab incisions with the help of various hooks (Varady, Oesch) and fine clamps (miniphlebectomy), Fig. 3 and 4). Insufficient perforating veins are localized via small skin incisions and ligated at the level of their fascial penetration.

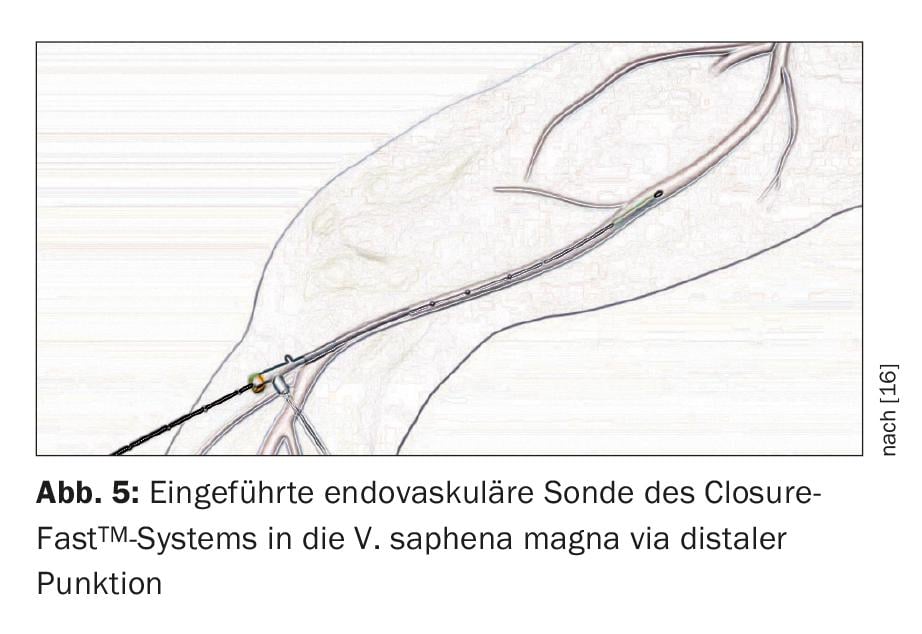

Since the late 1990s, various endovenous, minimally invasive procedures have been available as an alternative. For truncal vein treatment, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and endovenous laser therapy (EVLT) have proven most effective to date. In both methods, a probe is inserted ultrasound-guided into the insufficient truncal vein from distal to the groin or popliteal corse via a system of sheaths. (Fig. 5). After application of a perivenous fluid sheath to protect the surrounding area and, if necessary, anesthesia (tumescence), the insufficient vein is denatured and “sclerosed” from the inside by local heat generation, and the probe is slowly pulled out over its entire length. Both methods dispense with crossectomy.

For minimally invasive treatment of side branch varices, sclerotherapy is the established method. In this procedure, targeted intraluminal injection of a tissue toxic drug into the varicose vein produces local chemical endothelial damage leading to obliteration.

Differential indication

The indication for surgical treatment of varicose vein disease is always relative as long as thrombophlebitis, recurrent bleeding, or venous ulcers have not yet occurred, especially when aesthetic considerations are paramount.

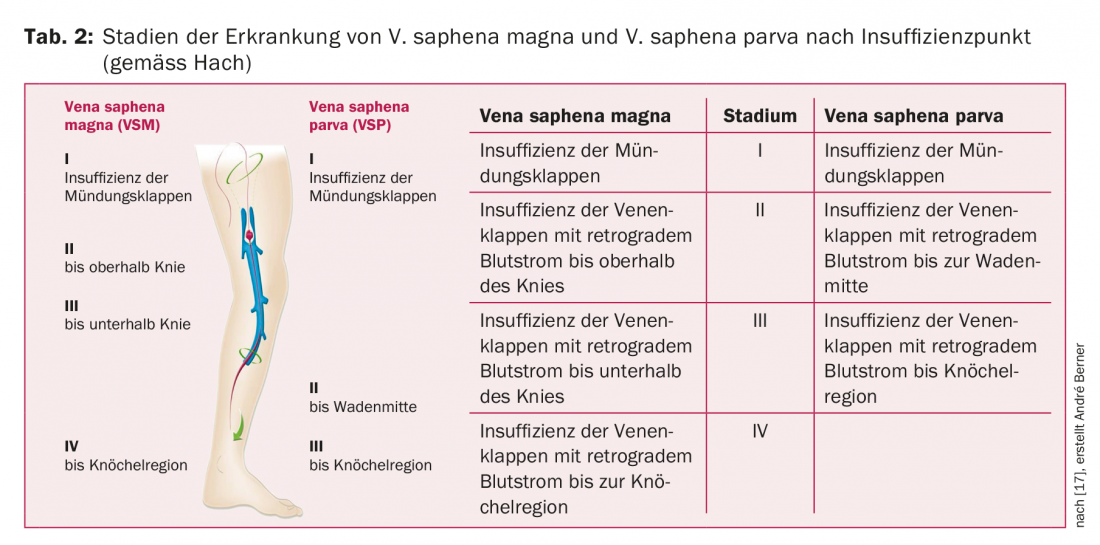

In principle, the time of treatment depends on the patient’s symptoms, while the treatment is based on the anatomical localization and the clinical stage (tables 1 and 2). The goal of therapy is to normalize venous hemodynamics and thus the consequences of congestion (swelling, edema, trophic disorders) [8]. As soon as a truncal vein is affected, a choice can be made between sclerotherapy, classic varicose vein surgery or endovenous truncal vein ablation.

A 1993 randomized trial demonstrates that surgical management is superior to compression therapy alone in patients with stage C2-3 disease [10]. However, later randomized trials failed to demonstrate clear advantages and disadvantages in comparisons between surgical variceal stripping and endovenous therapy, at least in terms of early outcomes [9,11].

Nesbitt et. al. have shown in a 2014 meta-analysis that endovenous procedures provide at least as good results as open surgery in follow-up up to five years. However, the studies compared were very heterogeneous, so that the validity is subject to certain limitations [13]. The UK NICE (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence) guidelines recommend endovenous procedures for the treatment of truncal venous insufficiency even before traditional varicose vein surgery, mainly because of their cost-effectiveness [14]. However, this assessment is not directly transferable to Switzerland because of the different cost and tariff structures [15].

The decision for a specific ablation procedure can thus be made individually and is ideally based on the clinical picture (e.g., associated thrombophlebitis, stasis dermatitis, ulcers), the duplex sonographic findings (morphology, course and diameter of the veins), the experience of the treating physician, comorbidities and, last but not least, the patient’s wishes.

Classical varicose vein surgery knows no morphological limitations and is therefore always feasible and, given the indication, never wrong. For a sustainable endovenous treatment, on the other hand, the following anatomical conditions are advantageously fulfilled:

- The truncal vein (V. saphena magna or V. saphena parva) should be at least. 1 cm below the skin to avoid skin damage from the applied thermal energy.

- The variceal diameter should not exceed a maximum of 10-15 mm [12], otherwise recurrences due to insufficient ablation increase.

- There should be neither previous thrombophlebitis with complete venous obliteration nor severely tortuous venous course. Both may make endovenous passage of the ablation probe impossible.

If these conditions are not met, crossectomy with variceal stripping is still the treatment of choice. In the presence of isolated recurrence of the cornea, surgical recrossectomy is also the treatment of choice.

Complications

Comparing the most frequent complications, wound healing disorders are found in 3-10% of cases after open varicose vein surgery. Nerve injuries are encountered in 7-39% but are rarely clinically relevant, and deep venous thrombosis is found in 0.5-5% of patients [12].

After endovenous treatment, serious complications such as deep vein thrombosis or skin burns are rarely observed in well-selected patients ( <0.5% each). The guidelines report local paresthesias at 3%, thrombophlebitis at 1%, ecchymosis at 6%, and hyperpigmentation of the skin at 2% [12].

Serious complications after sclerotherapy are also rare (<1%). Mainly headache (4%), thrombophlebitis (5%) and skin changes (hyperpigmentation 18%) occur [12].

Summary

After a century of proven surgical varicose vein therapy using vein stripping, equivalent minimally invasive procedures have become established over the past three decades, leading to an increasing shift in treatment numbers. The development of materials and technology, the independence from the operating room, the good early results, the high patient acceptance, and not least the resulting opening of varicose vein treatment to non-surgical subjects favor low-threshold treatment indications and thus contribute to a possible expansion of treatment numbers, which must be critically evaluated. The indication for treatment must be strictly based on clinical criteria (e.g., CEAP) and the extent of insufficiency (e.g., Hach stages) and not on the availability of the treatment method. Ideally, the available methods do not compete with each other, but complement each other to form a complete treatment spectrum within which the optimal therapy can be tailored for each patient. Such comprehensive treatment concepts improve outcomes and make varicose vein treatment increasingly attractive not only for patients but also for the physicians involved.

Despite modern procedures, classical varicose vein surgery has not lost its justification, but is increasingly specializing its range of indications to the limits of endovenous procedures.

Regardless of the therapeutic method chosen, it is crucial to inform the patient comprehensively about all available methods, their specific advantages and disadvantages, possible risks of complications, and the expected improvement in quality of life. An optimally informed patient is not only better able to understand the recommendations of his physician, but will also better support the decision for certain therapy procedures with all their consequences.

Take-Home Messages

- In the case of tired, heavy legs or a tendency to swelling in the evening, a venous insufficiency diagnosis should be considered even without superficially visible varices.

- The indication for surgery is relative if the clinical picture is uncomplicated (CEAP: C0-C3): Conservative measures to alleviate symptoms may be sufficient.

- In case of advanced or complicated clinical picture (CEAP: C4-C6, variceal bleeding, thrombophlebitis, stasis dermatitis, ulcers), surgery is indicated.

- Invasive treatment options include classic variceal stripping, sclerotherapy, and minimally invasive endovenous treatments (laser therapy, radiofrequency ablation).

- Treatment should be individualized: If the anatomical conditions are ideal, minimally invasive procedures are usually preferable; in all other cases, classic variceal stripping is still the treatment of choice.

Literature:

- Noppeney T: History of varicose vein treatment. In: Noppeney T, Nüllen H, eds: Diagnosis and therapy of varicosis. Heidelberg: Springer, 2010: 3-7.

- Rabe E, Pannier-Fischer F, Bromen K, et al: Bonn Vein Study of the German Society of Phlebology. Epidemiological study on the question of frequency and severity of chronic venous diseases in the urban and rural residential population. Phlebology 2003; 32(1): 1-14.

- Nicolaides AN, Hussein MK, Szendro G, et al: The relation of venous ulceration with ambulatory venous pressure measurements. J Vasc Surg 1993; 17(2): 414-419.

- Araki CT, Back TL, Padberg FT, et al: The significance of calf muscle pump function in venous ulceration. J Vasc Surg 1994; 20(6): 872-877.

- Eklof B, Perrin M, Delis KT et al: Updated terminology of chronic venous disorders: the VEIN-TERM transatlantic interdisciplinary consensus document. J Vasc Surg 2009; 49(2): 498-501.

- Babcock WW: A new operation for the extirpation of varicose veins. NY Med J 1907; 86: 153-156.

- Brand FN, Dannenberg AL, Abbott RD, et al: The epidemiology of varicose veins: the Framingham Study. Am J Prev Med 1988; 4(2): 96-101.

- Cheatle TR, Chittenden SJ, Coleridge Smith PD, et al: The effect on skin blood flow of short-term venous hypertension in normal subjects. Angiology 1991; 42(2): 114-122.

- Darwood RJ, Theivacumar N, Dellagrammaticas D, et al: Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation with surgery for the treatment of primary great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg 2008; 95(3): 294-301.

- Michaels JA, Brazier J, Campbell W, MacIntyre J, Palfreyman S, Ratcliff J: Randomised clinical trial comparing surgery with conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins. Br J Surg 2006; 93(2): 175-81.

- Rasmussen LH, Bjoern L, Lawaetz M, et al: Randomized trial comparing endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein with high ligation and stripping in patients with varicose veins: short-term results. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46(2): 308-315.

- Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, Dalsing MC, et al: American.

- Venous ForumThe care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2011; 53(5. Suppl.): 2-48.

- Nesbitt C, Bedenis R, Bhattacharya V, et al: Endovenous ablation (radiofrequency and laser) and foam sclerotherapy versus open surgery for great saphenous vein varices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 7: CD005624.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre, ed: Varicose Veins in the Legs. The Diagnosis and Management of the Varicose Veins. NICE Clinical Guidelines 2013; 168.

- Rosemann A: Guideline Varicosis. Medix, as of 2016. www.medix.ch/media/medix_gl_varikose_2016.pdf (accessed 7/3/2018).

- Medtronic. http://medtronicendovenous.com/patients/7-1-closurefast-procedure (accessed 7/3/2018).

- Hach W, Girth E, Lechner W: Classification of truncal varicosis of the great saphenous vein into four stages. Phlebu Proctol 1977; 6: 116-123.

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(4): 25-29