Case Report: The four-year-old patient in Figure 1 presented with episodic papules and hemorrhagic crusted vesicles. The mother reported that three to four months earlier, barely itchy “pimples” – especially on the décolleté and trunk – had appeared for the first time. Since then, repeated relapses have occurred. During a vacation at the seaside, the skin condition had improved significantly, but afterwards at home further and more pronounced relapses occurred again. The girl was always in excellent general health, reported minimal itching, and was hardly affected by the skin lesions. Previous personal history and family history were unremarkable.

Findings: Extensive erythematous, partially hemorrhagic encrusted papules are seen on the entire integument with emphasis on the trunk. Face, mucous membranes and capilitium are omitted (Fig. 1).

Quiz

Based on this information, which diagnosis is the most likely?

A Varicella

B Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP)

C Insect sting reaction

D Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA).

E Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

F Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Diagnosis and Discussion: The history as well as the clinical picture are highly characteristic for the presence of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) (Answer D). A biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis and exclude other differential diagnoses. This revealed a massive interface dermatitis with multiple apoptotic keratinocytes and a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate in the upper and middle corium, consistent with the suspected diagnosis of PLEVA.

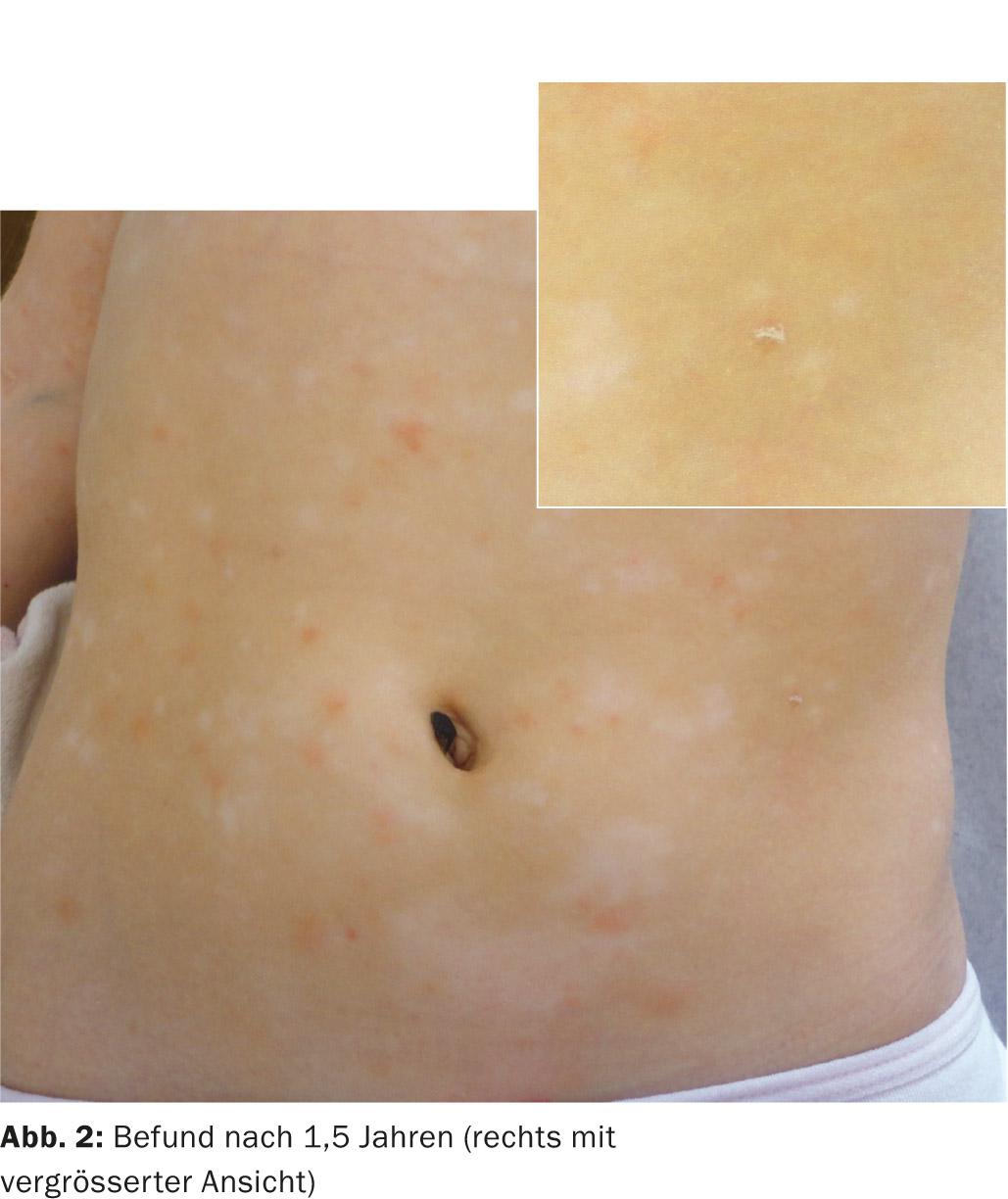

In addition to topical steroids, we initially used peroral therapy with erythromycin p.o. (40 mg/kg/KG for three weeks). Unfortunately, anti-inflammatory therapy did not result in significant improvement of the skin condition. However, in the subsequent year and a half, episodes were much less frequent. In contrast to the initial presentation with vesicles and hemorrhagic encrusted papules, increasingly erythematous papules with a central oblate scale and disseminated hypopigmented lesions were now seen, consistent with the transition to pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC, Fig. 2).

Pityriasis lichenoides, with its two clinical presentations PLEVA and PLC, is not uncommon in childhood, with PLEVA showing a peak of disease between two and three years of age, and PLC between five and seven years of age. However, occurrence is possible at any age. Spontaneous healing is usually expected, and the disease can last from a few weeks to several years. A retrospective study of 71 children with PLEVA [1] showed a median disease duration of 18 months (4-108). As in our patient, lesions of a PLEVA and PLC may be present simultaneously [2] and eventually progress to a PLC, although a PLC may already be present initially without acute lesions.

The pathogenesis and etiology remain unknown. Generally, a reactive, probably infection-triggered hypersensitivity reaction is now assumed. Since clonal T-cell subpopulations are sometimes found in the infiltrates, PLEVA is also discussed as a primary lymphoproliferative disease, but this has not been clearly confirmed so far [1].

Transitions of pityriasis lichenoides into usually CD 30+ cutaneous T-cell lymphoma have been described in previous literature [3]. However, this is controversially discussed and is likely to correspond – if at all – to individual cases. These patients may have had lymphomatoid papulosis at baseline, an important differential diagnosis of PLEVA.

If PLEVA is suspected, we recommend performing a small skin biopsy in addition to a laboratory check (differential blood count and routine chemistry) to confirm the diagnosis. If the findings are unremarkable, no further diagnostic measures are required.

Data on therapy for PLEVA in children is limited; generally, a trial of therapy with macrolide antibiotics (erythromycin 30-50 mg/kg/d for three weeks, or tetracyclines in older children) is recommended. Here, the focus is on the anti-inflammatory effect of the macrolide antibiotics. In therapy-resistant or chronic courses, phototherapy with UVB 311 nb may be considered, especially in older children and adolescents. Rare highly acute courses require systemic steroids, at most in combination with methotrexate.

Due to the chronic course in our patient, we discussed with the family the initiation of light therapy, but it has been declined so far with very little distress.

Literature:

- Ersoy-Evans S, et al: Pityriasis lichenoides in childhood:a retrospective review of 124 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2007; 56: 205-210.

- Fernandes NF, et al: Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. International journal of dermatology 2010; 49: 257-261.

- Fortson JS, Schroeter AL, Esterly NB: Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (parapsoriasis en plaque). An association

- with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in young children. Archives of dermatology 1990; 126: 1449-1453.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(1): 26-27