Proteinuria must always be taken seriously. Further clarification depends on the clinic, the severity of proteinuria, and whether there is concomitant microhematuria and/or renal insufficiency. If glomerular disease is suspected, a kidney biopsy is needed for accurate diagnosis. The focus of antiproteinuric therapy is proper blood pressure control and lowering of intraglomerular pressure using blockers of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Immunosuppressive therapy is indicated for specific glomerular diseases. The following article provides an overview of these different possibilities and presents some casuistry for illustration.

Family physicians and specialists face an ever-increasing number of older patients. This patient group increasingly includes patients with end-stage renal disease. Renal replacement therapy can be life-saving in these patients. In addition to the financial costs, such treatments are costly and often tedious for the affected patient. Therefore, everything should be done to avoid or, if not otherwise possible, at least delay entering this situation of terminal renal failure. To get closer to this goal, it is important to recognize the most common symptoms and causes of kidney disease at an early stage. Indications of renal disease include proteinuria, with/without microhematuria, elevated serum creatinine, and elevated blood pressure. Advanced disease is accompanied by edema and symptoms of uremia such as fatigue, weight loss, and nausea [1–3].

Proteinuria is either an incidental finding on routine examination – and therefore often without symptoms – or it is accompanied by systemic symptoms such as edema in nephrotic syndrome or other signs of generalized disease. More “innocuous causes” of proteinuria include status febrilis from influenza, intense physical activity, dehydration, or menstrual bleeding. A very rare cause may be Munchausen’s disease, where foreign protein (e.g. from chickens) is added to the patient’s own urine. This can be detected in urine protein electrophoresis.

Glomerulonephritis isolated or in systemic disease such as multiple myeloma is one of the serious causes of proteinuria. In isolation, proteinuria is a common sign of kidney disease. For proteinuria to be symptomatic, it requires larger amounts of protein in the urine. Severe proteinuria, as in nephrotic syndrome, may be manifested by foaming of the urine, accompanied by generalized edema [3, 4]. Regardless of the severity of proteinuria, it should always be taken seriously as it is associated with progressive kidney disease.

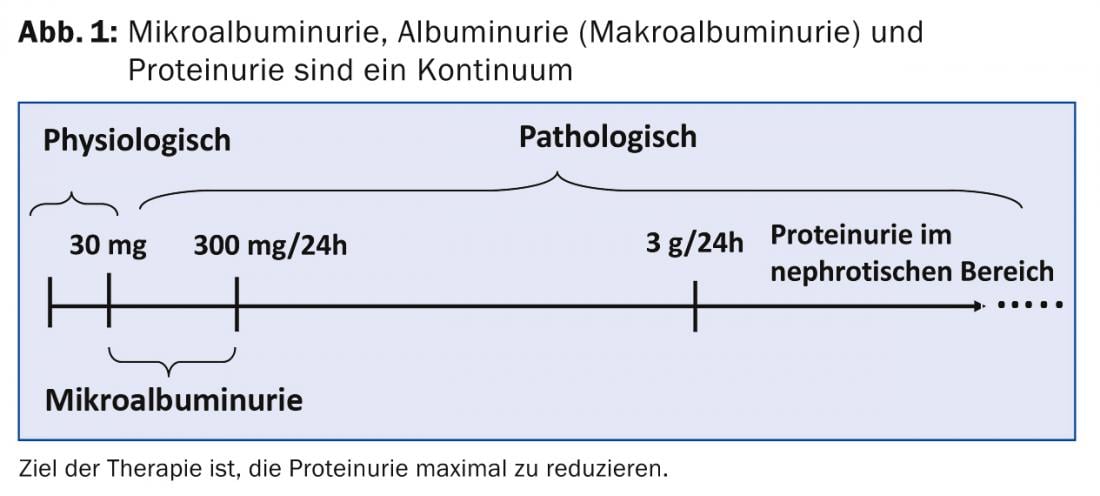

Proteinuria – a continuum

Proteinuria is a continuum. Low values are considered physiological. If mainly albumin is excreted, we speak of microalbuminuria. If more than 300 mg/d albumin or protein is excreted, it is proteinuria. If there are large amounts of protein in the urine, i.e., more than 3 g/d, we speak of proteinuria in the nephrotic range or even of a nephrotic syndrome (Fig. 1).

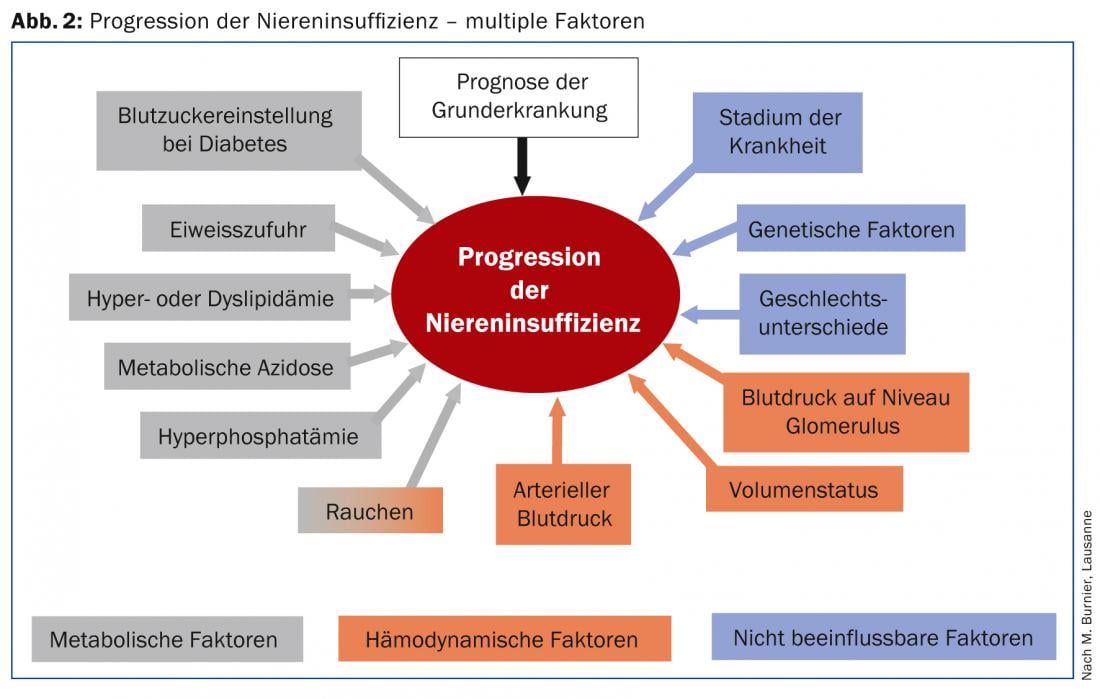

Proteinuria is one of the factors contributing to the deterioration of renal function (Fig. 2).

Causes of proteinuria

Proteinuria can have several causes. As discussed above, fever, great exertion, etc., may cause transient proteinuria; otherwise, a renal cause must be sought (Table 1) . Proteinuria >3 g/d and proteinuria associated with microhematuria are glomerular in origin. Mild proteinuria may or may not be glomerular in origin. Glomerular disease must be further clarified with a renal biopsy [1–3].

Case description 1

A 19-year-old young man had microhematuria and two episodes of macrohematuria, the first after a minor traffic accident, the second during an upper respiratory tract infection. Blood pressure was 110/65 mmHg, sitting; heart rate 72/min, reg. No edema on clinical examination.

Renal function was mildly impaired with serum creatinine of 108 µmol/l. Microhematuria and proteinuria were noted in the urine stix. 24-h urine collection revealed proteinuria of 1.5 g/d.

A renal ultrasound showed no pathologic findings. Based on the microhematuria and proteinuria, a renal biopsy was performed. Histopathological examination revealed a “maladie de Berger,” i.e., IgA nephropathy (deposits of IgA in the mesangium), with signs of activity in terms of glomerular crescents. Steroid therapy was given for six months and treatment with an ATII blocker was started (the ACE inhibitor was not tolerated). Under steroid therapy, hypertension worsened and the dose had to be reduced. One year after treatment, blood pressure was normal on ATII blocker and proteinuria <0.3 g/d.

This case report illustrates the need for accurate diagnosis by renal biopsy in a young patient with proteinuria. Immunosuppressive therapy was administered with good results, but side effects such as hypertension and weight gain occurred. Glomerulonephritis persists and may recur, so regular checks must be performed.

Case description 2

A 26-year-old young man from the Cape Verde Islands presented to the emergency for severe headache. He worked in the metal industry and had been having headaches for a week. He came straight from work because the pain was becoming unbearable, so his boss sent him straight to emergency.

Blood pressure lying at 270/130 mmHg. No edema. Serum creatinine 355 µmol/l, with microhematuria as well as proteinuria of 1 g/d. After lowering of blood pressure and persistence of proteinuria and detection of glomerular erythrocytes in urine, renal biopsy was performed. Histology revealed rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, i.e., aggressive IgA nephropathy with crescents and necrosis. In addition to blood pressure control, strong immunosuppression with steroids and cyclophosphamide was performed, with stabilization and eventual improvement of renal function.

Case description 3

A 52-year-old woman came to the consultation for evaluation of renal insufficiency. There was a history of long-standing untreated arterial hypertension, which was controlled by the primary care physician with amlodipine 10 mg, an ACE inhibitor, and hydrochlorothiazide. BP values were 125/82 mmHg sitting, heart rate 64/min. No edema was palpable. There was renal insufficiency with a serum creatinine of 214 µmol/l, and microalbuminuria (280 mg/d). Renal biopsy showed nephroangiosclerosis and severe chronic changes with interstitial fibrosis. The indication for renal biopsy can be discussed in this case. A wait-and-see approach would also have been justifiable. No change in therapy was performed.

Glomerular diseases

Glomerulopathies are caused by structural and functional damage to the renal glomeruli. They can be inflammatory or non-inflammatory. The term glomerulonephritis refers to an inflammatory change in the glomeruli. Examples of diseases of the glomeruli of non-inflammatory origin are diabetic nephropathy and amyloidosis [3].

The exact diagnosis can only be made with a kidney biopsy. There is hope that noninvasive methods will be available in the near future, such as biomarkers to diagnose membranous glomerulonephritis, or functional MRI to differentiate between glomerulonephritis and acute tubular injury. These methods are still under evaluation and it is too early to apply them routinely.

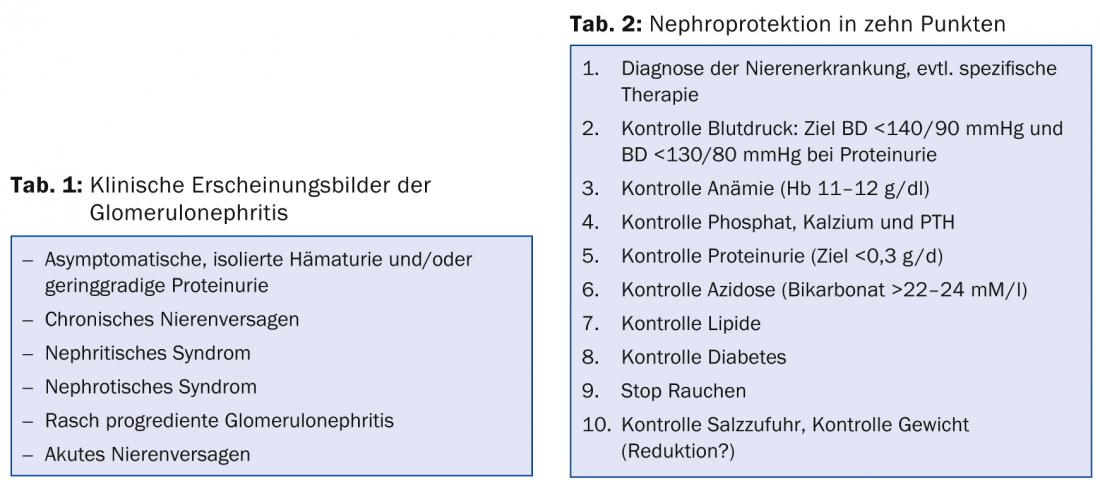

Glomerulopathies may arise as a primary renal disorder or secondary to systemic diseases, particularly diabetes mellitus, infections, vasculitides, or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The classification and nomenclature of glomerulopathies and specifically glomerulonephritis is complex. This is historically based on how renal disease is defined: histologically, based on clinic or history, or using genetic analysis or specific biomarkers. Table 1 lists the classic clinical presentations. Histology is required for specific immunosuppressive therapy.

Therapy

The therapy of proteinuria consists of two pillars: non-immunosuppressive and immunosuppressive therapy [5–8].

Non-immunosuppressive therapy is now referred to as “nephroprotection” and is summarized in Table 2. The most important factors for progression are high blood pressure and proteinuria. Therefore, good blood pressure control is very important. Lowering blood pressure also reduces proteinuria. Furthermore, insertion of blockers of the renin-angiotensin system (ACE inhibitors, ATII blockers) lowers intraglomerular pressure, which leads to reduction of proteinuria.

These include cessation of smoking, good lipid control, control of anemia, calcium/phosphate metabolism, acidosis, and weight loss, etc. This can often slow down the progression of kidney disease and even block it in certain situations.

The indication for immunosuppressive therapy is based on the exact diagnosis with histology of the renal tissue. Since these are immunosuppressive therapies with sometimes severe side effects, these treatments belong in the hands of a renal specialist [3, 4].

Summary

The most important goal of treatment for renal patients is and remains to avoid or, if not possible, at least to delay the development of end-stage renal failure. Patients with evidence of glomerulonephritis must be rapidly evaluated and the indication for renal biopsy considered. Only an accurate diagnosis makes it possible to initiate a suitable therapy. In addition to specific therapy of kidney disease, it is important to initiate so-called “nephroprotection”, i.e. kidney-protective measures as discussed above.

In the continuing care of these patients, close collaboration between the primary care physician and nephrologist is important for optimal therapy to treat the underlying disease and control blood pressure, anemia, and hyperparathyroidism. Additional noxae such as renal toxic drugs or smoking must be avoided.

Prof. Dr. med. Bruno Vogt

Literature:

- Bourquin V, Giovannini M: Proteinuria. Part 1. pathophysiology, detection, quantification. Switzerland Med Forum 2007; 7: 708-712 (Curriculum).

- Bourquin V, Giovannini M: Proteinuria. Part 2. procedure for clarification and care. Significance of microalbuminuria. Switzerland Med Forum 2007; 7: 730-734 (Curriculum).

- Marti HP, et al: Glomerulopathies. Schweiz Med Forum 2003; 46: 1108-1117 (Curriculum).

- Hricik DE, Chung-Park M, Sedor JR: Glomerulonephritis. New Engl J Med 1998; 339: 888-899 (Review).

- Ruggenenti P, Schieppati A, Remuzzi G: Progression, remission, regression of chronic renal diseases. The Lancet 2001; 357: 1601-1608 (Review).

- De Seigneux S, Martin PY: Management of patients with the nephrotic syndrome. Swiss Med Wkly 2009; 139: 416-422 (Review).

- Krapf R: Rising creatinine. Switzerland Med Forum 2006; 6: 813 (Editorial).

- Charlesworth JA, Gracey DM, Pussell BA: Adult nephrotic syndrome: non-specific strategies for treatment. Nephrology 2008; 13: 45-50 (Review).

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Any proteinuria should be taken seriously and clarified.

- The indication for histologic diagnosis by percutaneous renal biopsy must be made early.

- Care of patients with proteinuria includes close monitoring of renal function, proteinuria, and arterial blood pressure.

- The decision for additional immunosuppressive therapy is based on the histologic diagnosis and the exact cause of the kidney disease.

- Rapidly progressive proteinuria and/or renal failure is a medical emergency.

A RETENIR

- Toute protéinurie est à prendre au sérieux et doit être investiguée.

- L’indication d’un diagnostic histologique au moyen d’une biopsie rénale percutanée doit être posée précocement.

- La prise en charge de patients protéinuriques nécessite un contrôle étroit de la fonction rénale, de la protéinurie et de la pression artérielle.

- La décision d’instaurer un traitement immunosuppresseur complémentaire se base sur le diagnostic histologique et la cause exacte de l’affection rénale.

- La progression rapide d’une protéinurie et/ou d’une insuffisance rénale constitue une urgence médicale.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(3): 26-29