The terms interstitial l ung disease or diffuse lung parenchymal disease refer to a group of pathologies affecting the epithelium of the alveoli (alveolar epithelium), the endothelium of the pulmonary capillaries, the basement membrane, or the perivascular and perilymphatic tissues of the lung. Fibrosis may develop during the course of most ILDs.

The terms interstitial lung disease ( [ILD]) or diffuse parenchymal lung disease ( [DPLD]) refer to a group of pathologies that affect the epithelium of the alveoli (alveolar epithelium), the endothelium of the pulmonary capillaries, the basement membrane, or the perivascular and perilymphatic tissues of the lung. Bronchioles and bronchi are often additionally affected. For example, ILDs do not include obstructive airway disease or directly pathogen-related pneumonia. Fibrosis may develop during the course of most ILDs.

Division

The group of ILDs is heterogeneous and can be subdivided in different ways. The simplest classification is into so-called idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) on the one hand and ILDs with a known cause on the other. ILD can be caused by systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis or collagenoses as well as by external influences such as exogenous allergic alveolitis (EAA), pneumoconioses of drug toxicity or radiogenic pneumonitis.

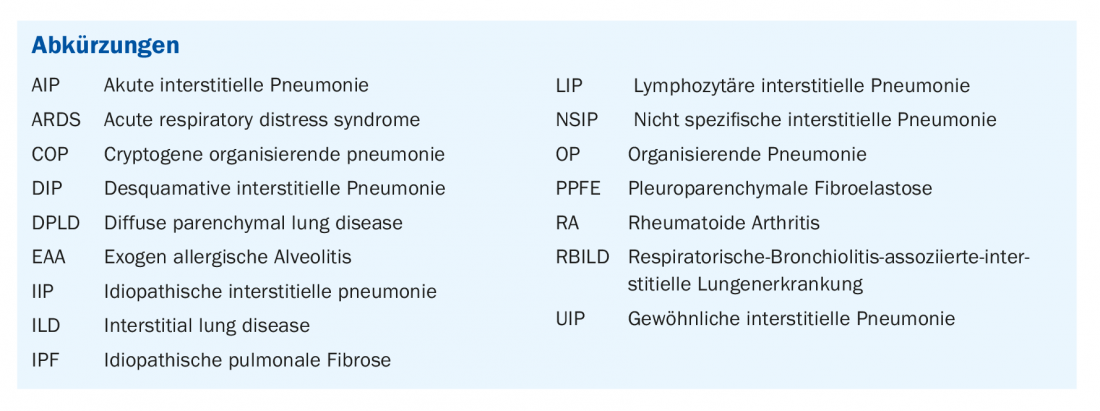

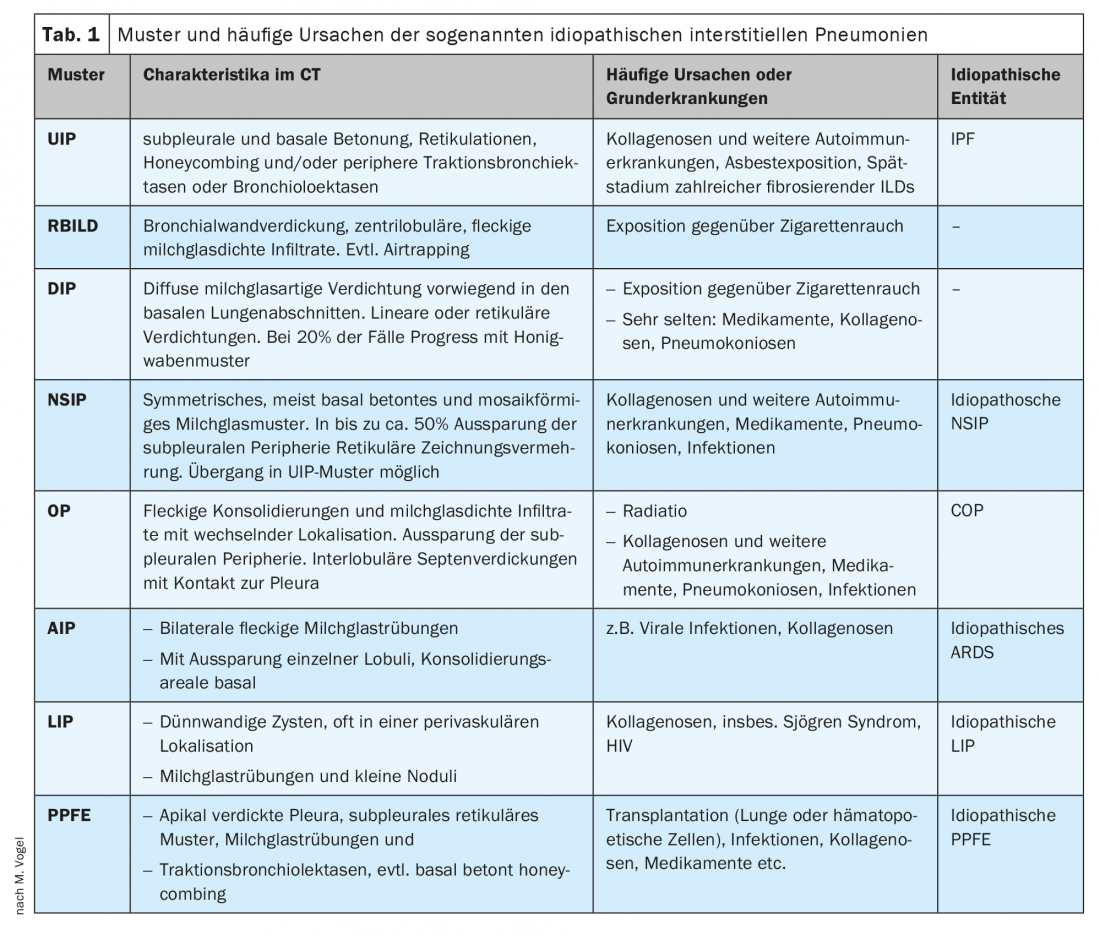

Among IIPs, thin-slice CT and histological specimens predominantly distinguish eight patterns and associated entities:

- The pattern of usual (“usual”) interstitial pneumonia (UIP) in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

- The pattern of respiratory bronchiolitis (RB) in respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease (RBILD).

- The pattern of desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) in eponymous DIP.

- The NSIP pattern in non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP).

- The pattern of organizing pneumonia (OP) in cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP).

- The pattern of acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) with the clinical presentation of ARDS.

- The LIP pattern in lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP).

- The pattern of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis in eponymous disease (PPFE).

These patterns are not synonymous with a disease. Rather, on the one hand, they may be idiopathically triggered or, on the other hand, various known causes may be present: Cigarette smoking for RBILD and DIP and, among others, collagenoses for UIP, NSIP, OP, LIP, and AIP [1] or viral pneumonias for AIP, NSIP, and OP (see Table 1 for patterns and common causes). There is no clear relationship between pattern and triggering disease: the same disease can trigger different patterns in different patients. In addition, the patterns show a different spectrum with sometimes large variations and similarities with other patterns. The gold standard for the diagnosis of ILDs is therefore the interdisciplinary consensus of at least pneumology, radiology and pathology [2,3]. Other specialist disciplines such as rheumatology must also be consulted on a regular basis. In this regard, although the pattern in thin-section CT is usually directional, this article will demonstrate the importance of all relevant disciplines and, in particular, the anamnestic and clinical information from the entire course of the disease for the diagnosis. The focus here will be on the classification of the UIP pattern.

UIP pattern and IPF

IPF is the most common and, with a median survival of 3-4 years, the most prognostically unfavorable IIP. The prevalence is 2-29 per 100 000, and the incidence is approximately 10 per 100 000/year [4]. Therapy with specific fibroblast inhibitors can delay progression but cannot reverse the disease [4]. Anti-inflammatory therapy, which is indicated in many other IIPs, has a negative impact on prognosis [5]. The UIP pattern present in IPF may also be non-idiopathic, e.g., in the setting of collagenoses, fibrosing EAA [6], after exposure to asbestos, or sarcoidosis.

A typical constellation for IPF is the following: Male gender, age over 60 years and smoking history, which may date back several years or alternatively an increased familial occurrence of IPF [3,7]. If no corresponding underlying disease or influence can be identified in a patient with a UIP pattern, the diagnosis of IPF is made. This is an independent, treatable disease whose genesis appears to be multifactorial. The “typical UIP pattern” (category 1) is characterized CT morphologically by subpleural and basal emphasis of fibrotic changes. Reticulations and a honeycomb-like lung skeleton, the so-called honeycombing pattern, with or without peripheral traction bronchiectasis or bronchioloectasis are found. Asymmetry occurs in approximately 25% [8].

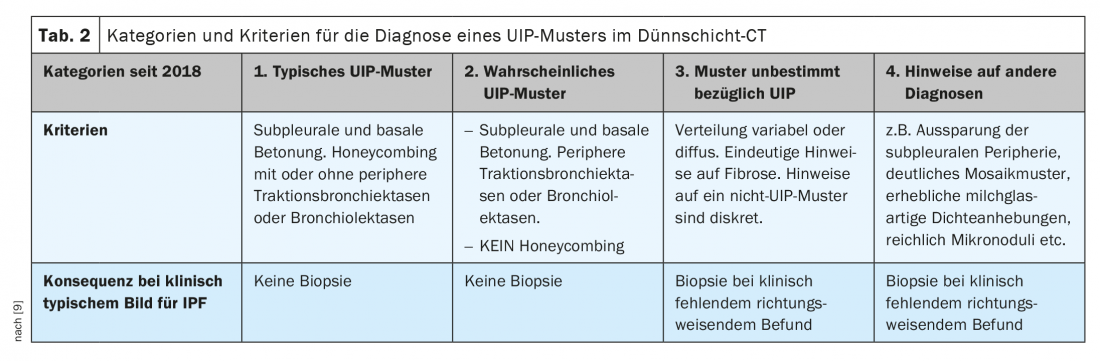

Not every case of IPF shows the typical morphological changes: If only the honeycomb pattern is absent, one speaks of a “probable UIP pattern” (category 2). In addition, clinical information is usually not fully available when the CT scan is reported. Therefore, first, the certainty or probability of a UIP pattern is determined based on the thin-slice reconstructed CT images. For this purpose, new criteria were defined in 2018 (Table 2) [9].

The consequence of the classification into one of the categories is guiding for the further diagnostic procedure. In a clinical context typical of IPF, lung biopsy is not performed for category 1 and 2. [3,7,9].

Category 1: typical UIP pattern

An 82-year-old patient presents with exertional dyspnea that has been progressive for 3-4 weeks. There is a cough without sputum. Exposure to hazardous materials has not occurred. The family history is unremarkable. Until 45 years ago, there was occasional nicotine abuse with a cumulative 4-5 pack-years.

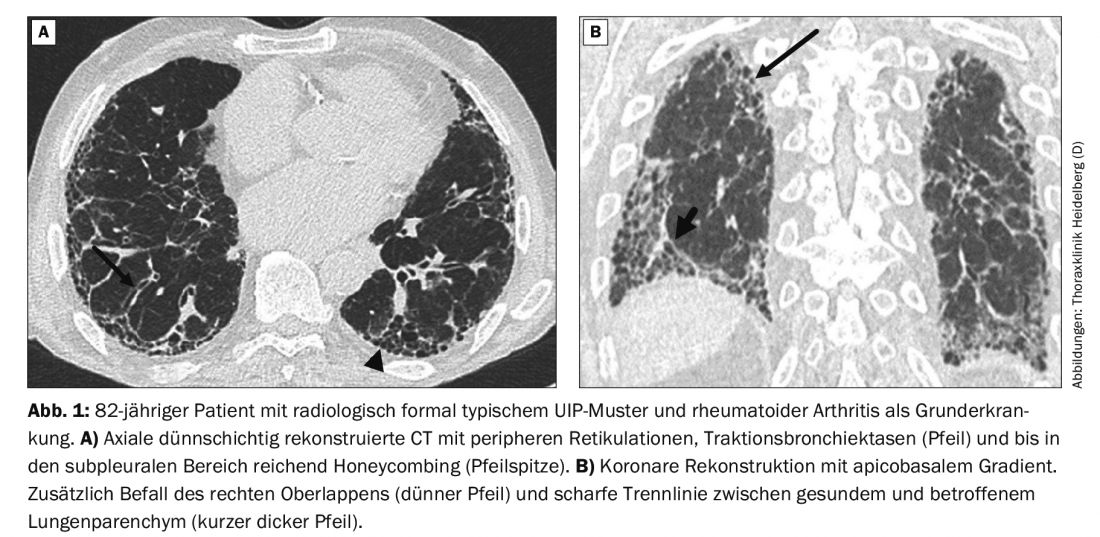

The subsequent native CT scan with thin-layer reconstructions shows a typical UIP pattern (Fig. 1A) . During the interdisciplinary discussion of the findings, it becomes known that the patient also suffers from rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Therefore, the diagnosis is not IPF but RA-associated ILD.

If an ILD pattern occurs in the setting of collagenosis, the prognosis for patients is better than in the case of IPF. Even with a formally typical, probable, or indeterminate UIP pattern, in some cases there is additional morphologic evidence in the lung parenchyma of association with autoimmune disease [10]. In the case of the 82-year-old patient, these are the additional involvement of the right upper lobe and the sharp oblique-horizontal dividing line between healthy and affected lung (Fig. 1B). However, these signs are not conclusive and can also be found in cases of IPF.

Data on the incidence of interstitial lung disease (ILD) directly caused by RA vary, because respiratory symptoms often appear late due to exercise limitation. Clinically significant ILD may occur in approximately 7% of RA patients [11]. However, radiological evidence of ILD (usually still asymptomatic) can be detected on thin-slice reconstructed native CT scans in up to 60% of RA patients [12]. Nicotine abuse, which may date back several years, also increases the risk of collagenosis-associated ILD with UIP pattern [13].

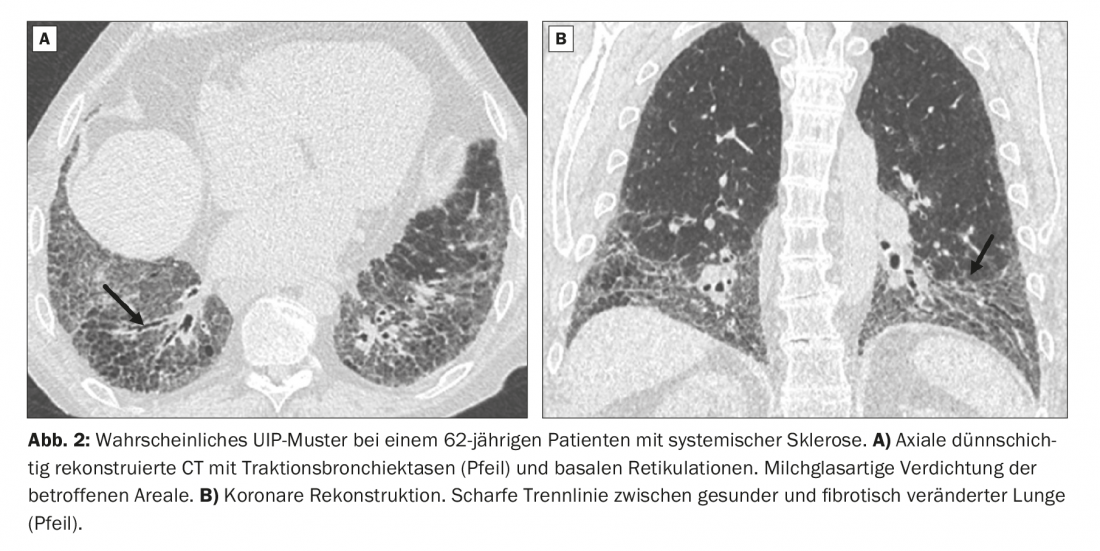

Category 2: probable UIP pattern

A 62-year-old patient presents with exertional dyspnea on mild exertion. Systemic sclerosis is already known. CT images show a striated pattern with peripheral traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis with subpleural and basal emphasis. In addition, slight milky glass-like density enhancement in the affected areas (Fig. 2A).

CT morphologically, the image formally corresponds to that of a probable UIP pattern and would have to be classified as such without knowledge of the history. In this case, however, the diagnosis is ILD in the setting of systemic sclerosis. The sharp horizontal dividing line between healthy and affected lung can be easily seen on the coronary reformatted CT images (Fig. 2B).

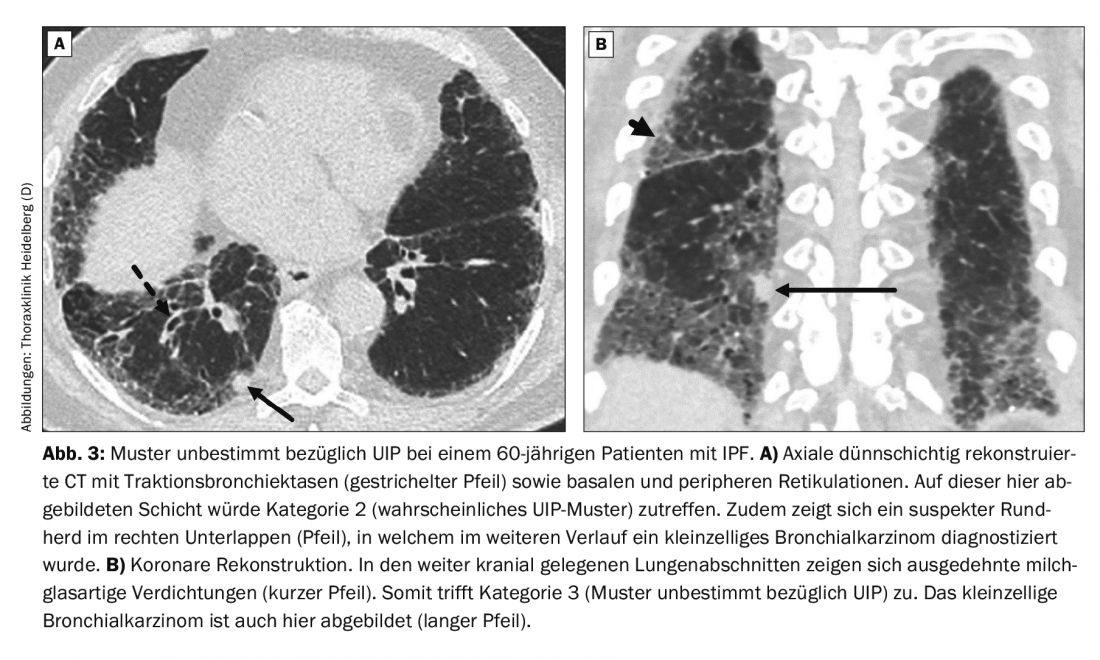

Category 3: Pattern indeterminate with respect to UIP or CT not indicative of any of the diagnoses.

A 60-year-old patient presents with dyspnea. Until 10 years ago, there was nicotine abuse with a total of 20 pack years. Allergies, autoimmune diseases or exposure to hazardous substances are not known. Thin-slice CT showed an indeterminate pattern with respect to UIP (Fig. 3). Histological examination of a subsequent surgical biopsy from the right lower lobe revealed a UIP pattern. IPF was diagnosed. An additional finding was small cell bronchial carcinoma.

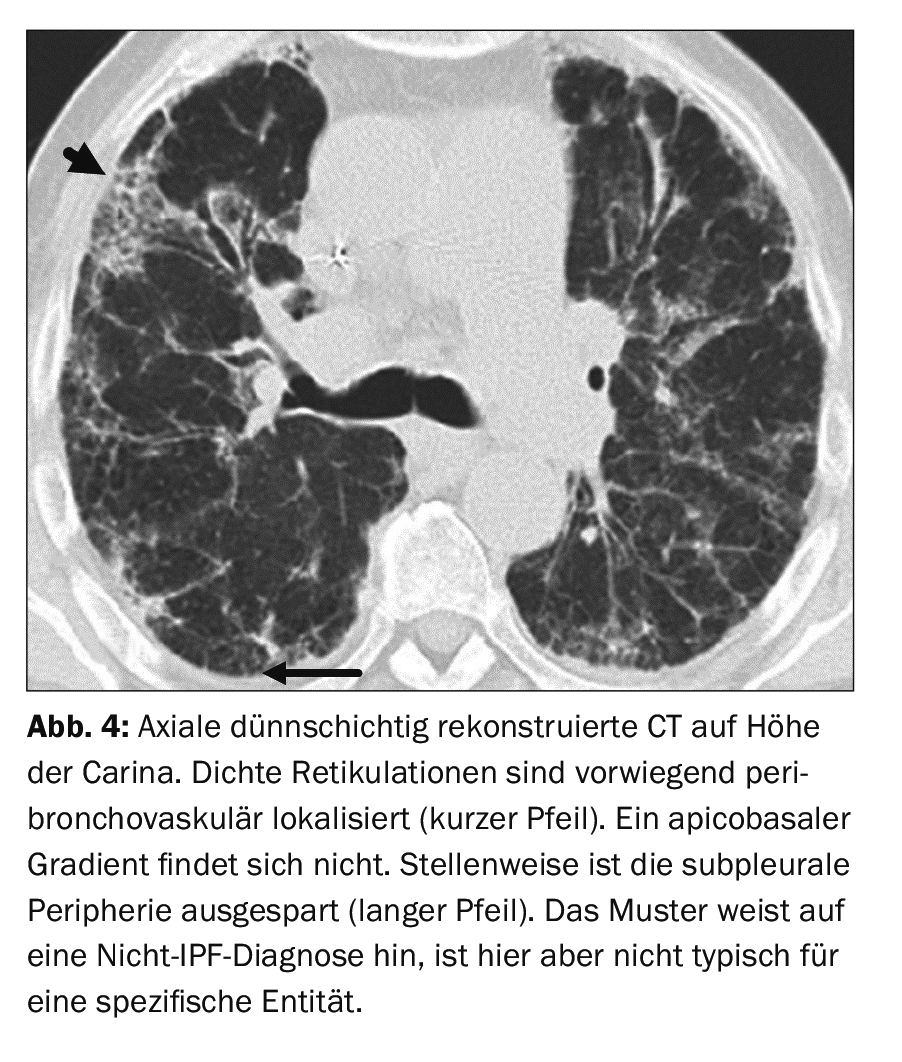

Category 4: morphologic evidence of a non-IPF diagnosis.

A 71-year-old patient with dilated cardiomyopathy and 5 years of therapy with amiodarone presents with slowly increasing dyspnea. Bodyplethysmography revealed moderately severe restrictive lung disease. The pattern on thin-slice CT is not compatible with a UIP pattern (Fig. 4). Inconsistent with a UIP pattern are, for example, the recess of the subpleural periphery and considerable milky-glass-like density elevations even outside the areas affected by fibrosis. There is an exception here: in pathogen-induced interstitial pneumonia or acute exacerbation of IPF, planar milky vitreous dense infiltrates in combination with preexisting fibrotic changes are the typical picture [14].

Consolidation may be indicative of surgery. Distribution predominantly peribronchovascular, perilymphatic, or exclusively in the apical or middle lung segments also indicates a non-IPF diagnosis. A distinct mosaic pattern, especially with three different density levels and/or micronodules are indicative of EAA (hypersensitivity pneumonia in English, corresponding to the term hypersensitivity pneumonia). Incidentally, a new guideline was also published for the diagnosis of EAA in 2020 [6]. In the case of the patient on Figure 4 , ILD due to drug toxicity was diagnosed. This disease does not have a specific or pathognomonic pattern.

Take-Home Messages

- The so-called idiopathic interstitial lung diseases have characteristic patterns on CT imaging.

- The gold standard for diagnosis of interstitial lung disease is interdisciplinary consensus (internal medicine, radiology, pathology).

- The UIP pattern is divided into 4 categories.

- The radiologic classification of the UIP pattern, in combination with clinical data, has a direct impact on the decision for or against additional lung biopsy and on the treatment decision.

Literature:

- Capobianco J, et al: Thoracic Manifestations of Collagen Vascular Diseases. RadioGraphics 2012; 32: 33-50.

- Travis WD, et al: An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188: 733-748.

- Lynch DA, et al: Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Fleischner Society white paper. The Lancet Respiratory medicine 2018; 6: 138-153.

- Behr J: Diagnostics and therapeutic options in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Dtsch Arztebl International 2013; 110: 875-881.

- Raghu G, et al: Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1968-1977.

- Raghu G, et al: Diagnosis of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis in Adults. An Official ATS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: e36-e69.

- Brownell R, et al: The use of pretest probability increases the value of high-resolution CT in diagnosing usual interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 2017; 72: 424-429.

- Tcherakian C, et al: Progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: lessons from asymmetrical disease. Thorax 2011; 66: 226-231.

- Raghu G, et al: Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2018; 198: e44-e68.

- Chung JH, et al: CT Features of the Usual Interstitial Pneumonia Pattern: Differentiating Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease From Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. American Journal of Roentgenology 2017; 210: 307-313.

- Turesson C, et al: Extra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis: incidence trends and risk factors over 46 years. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2003; 62: 722-727.

- Brown KK: Rheumatoid lung disease. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 2007; 4: 443-448.

- Kumar A, et al: Current Concepts in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management of Smoking-Related Interstitial Lung Diseases. Chest 2018; 154: 394-408.

- Akira M, et al: Computed tomography findings in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 178: 372-378.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2021; 3(3): 6-10.