Pediatric patients are a very heterogeneous patient population. Wound dressings must be adapted to the skin structure of the affected child. Primary healing wounds should be protected from mechanical friction. The potential of rapid cell regeneration in childhood can be optimally exploited. Good pain management is essential from the initial wound care.

The age range of pediatric patients is from neonates (including premature infants) to adolescent youth aged 16-18 years. Children’s skin is very sensitive and can react very quickly to pressure or mechanical impact with slight, usually harmless redness or superficial skin lesions, which usually disappear again on their own. heal.

Both after birth and during puberty, a child’s skin changes significantly. Thus, the skin of a premature baby has physiological and anatomical peculiarities that are associated with corresponding risks. As the largest organ in the preterm infant, the skin accounts for approximately 13% of body weight, as opposed to 3% in the adult [1]. Already from 27-29. During the first week of pregnancy (SSW), all the anatomical structures of the skin are in place, although not yet in a mature form. Only in the 32nd week of gestation and the subsequent further intrauterine maturation until the regular date of birth does the stratum corneum form sufficient protection. After birth, an accelerated maturation process of the skin takes place, so that approximately two weeks postnatally, regardless of the degree of any prematurity, the epidermis protective function is guaranteed [2]. Not only after birth, but also in adolescence, significant changes in the skin occur due to hormonal changes in the organism [1].

Aspects of wound healing

It can generally be assumed that children have primary healing wounds in most cases. Due to the growth of the child and the changing skin structure described above, especially in infancy and adolescence, wound care and treatment must always be adapted according to the age, skin and conditions of the affected areas of the body. Wound dressings are usually not tested by the manufacturers in children and certainly not in different age groups, and experiences from wound treatment in adult patients are often transferred unreflectively to children. It is apparent that the individual needs and requirements of children at different ages are not always taken into account [3].

Taking into account the child’s skin structures, the following aspects are of central importance concerning wound healing in children:

- The skin of the premature/newborn and infant in the first year of life is 60% thinner than the skin of adult patients and therefore susceptible to lesions from dressings, adhesion to the wound and wound edges, and skin tears.

- Skin regeneration, especially in the granulation phase, is significantly faster in children than in adults (greater number of fibroblasts; collagen and elastin production is increased in children).

- The skin as an organ grows rapidly, especially in young children under the age of five.

Scars potentially grow more slowly than the non-scarred surrounding skin and can thus cause functional limitations after only a short time.

Children are therefore not small adults in terms of wound healing and require qualified wound care tailored to the needs of pediatric patients. Pediatric patients with chronic diseases or in the context of intensive and life-sustaining treatments are found to be prone to wound healing disorders or chronic wound healing. These more difficult wound healing issues require the expertise of a multidisciplinary team specializing in pediatric wound care; they are not highlighted in this article.

Wound dressings

To ideally support primary wound healing in children, wounds require protection from mechanical friction. In this way, wound regeneration is not disturbed. Depending on the age of the child, localization and size of the wound, a wound dressing is no longer necessary after approx. 48 hours. Disinfection of the inconspicuous wound is usually not necessary, since the tissue is already closed during the first wound inspection.

In general, children have some peculiarities compared to adult patients, which also influence the choice of appropriate wound dressings [3–5]. First, small and flexible dressings are usually needed for children. The wound dressing must therefore either be available in small sizes or it must be possible to cut it to size accordingly [3]. Fixed borders often do not correspond to the contour of a child and are therefore only suitable to a limited extent. Furthermore, it is usually not necessary to use wound dressings with very high absorbency, because wound secretion in children is usually minimal and therefore less of a problem.

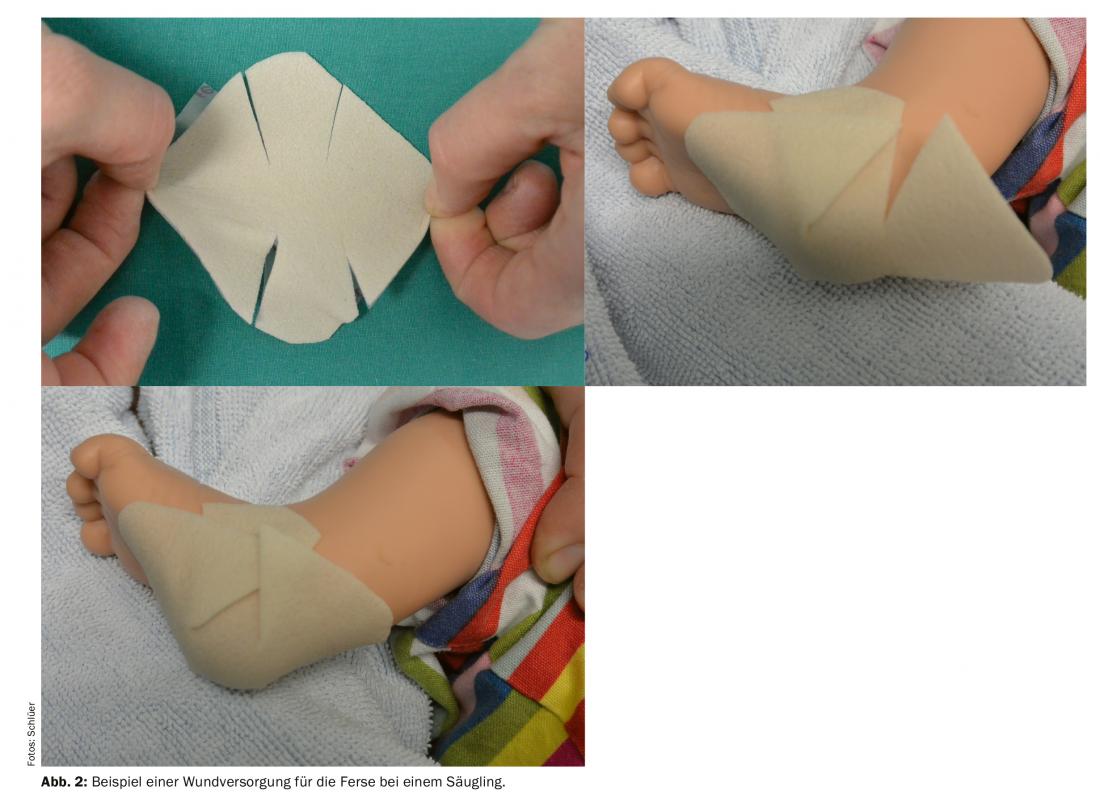

On the one hand, children can experience retraumatization through a dressing change, which reminds them of their accident event, for example. In addition, the anxiety and pain experienced during a dressing change often severely affect the well-being of the child as well as that of his or her family. Fear and pain, as two mutually reinforcing phenomena, cannot always be clearly separated. Accordingly, distinguishing whether a child is now primarily afraid of the pain or really in pain during a dressing change is often difficult. Therefore, it is essential to use wound dressings in pediatrics that are easy to apply, allow long intervals between dressing changes, do not stick to the wound and allow atraumatic dressing changes at any time. It is apparent that suitable wound dressings for children must be one thing above all – flexible in their use (box, Fig. 2).

There are several guidelines available on wound management in adult patients – general guidelines for chronic and general wounds, but also specific guidelines for wounds such as pressure ulcers [6,7]. To the best of the author’s knowledge, there is still no wound treatment guideline adapted to the needs of children of different ages. Although attention must be paid to the ingredients of a dressing, they are not tested for all ages. Similarly, there is a lack of knowledge about the long-term effects of silver-containing dressings in premature infants, neonates, and young children or about the effects of calcium in alginate products in this age group.

Preventing retraumatization, involving the child

Adapted and adequate pain management around dressing changes is imperative to counteract retraumatization of the child and his or her entire family.

Furthermore, it is indispensable to prepare the affected child for an upcoming dressing change with the involvement of his or her family and in an age-appropriate manner and also to involve the child during the intervention [4,5]. This creates a good condition for a child to tolerate a parent removing the dressing and the child reapplying the dressing him/herself. It is useful to explain each step to the child and to perform them slowly.

Likewise, teddy bears and dolls provide a welcome distraction. They can also act as “first-time patients” for whom the dressing change can initially be performed in a playful manner and thus shown to the child (Fig. 1).

Conclusions and recommendations for clinical practice

It is imperative for clinical practice to have present the various aspects that influence wound care in children. Thus, the correct choice of wound dressing must counteract re-traumatization of the skin and the child’s psyche. The child’s activity and freedom of movement are the top priority and yet the wound must be protected from mechanical irritation. Children should be involved in dressing changes and wound care in a playful manner according to their age and capabilities, and their urge to perform actions themselves must not be curbed. It is also important to gain the trust of the family in order to be able to accompany the child in the best possible way. Consideration of the specifics of each age group, skin structure, and the needs of children for minimal manipulation guides the selection of the ideal dressing.

Take-Home Messages

- Pediatric patients are a very heterogeneous patient population.

- Wound dressings must be adapted to the skin structure of the affected child.

- Primary healing wounds should be protected from mechanical friction.The potential of rapid cell regeneration in infancy can be optimally exploited.

- Good pain management is essential from the initial wound care.

Literature:

- Butler CT: Pediatric Skin Care: Guidelines for Assessment, Prevention and Treatment. Dermatology Nursing 2007; 19(5): 471-486.

- Blume-Peytavi U, et al: Skin care practices for newborn and infants: review of the clinical evidence for best practices. Pediatric Dermatology 2012; 29(1): 1-14.

- Bahasterani MM: An Overview of Neonatal and Pediatric wound care knowledge and considerations. Ostomy Wound Management 2007; 53(6): 34-55.

- Bahasterani MM, et al: V.A.C. Therapy in the management of paediatric wounds: clinical review and experience. International Wound Journal 2009; 6(1): 1-26.

- Gabriel A, et al: Outcomes of vacuum-assisted closure for the treatment of wounds in a paediatric population: case series of 58 patients. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 2009; 62: 1428-1436.

- Fan K, et al: State of the art in topical wound healing products. Plastic Reconstructive Surgery 2011; 127(Suppl 1): 44S-59S.

- Warriner RA III, Carter MJ: The current state of evidence-based protocols in wound care. Plastic Reconstructive Surgery 2011; 127 (Suppl 1): 144S-153S.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2020; 30(2): 16-18