Diagnosis of bipolar disorder is complex and usually occurs late. Many bipolar people are misdiagnosed as unipolar depressive and treated only with antidepressants. The leading symptoms of mania (inadequate elevated mood, increased drive, accelerated thinking, and overestimation of self) should therefore always be taken into account and interrogated. Drug therapy for bipolar disorder (atypical antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, lithium, and combinations thereof) is challenging and is usually discontinued by the psychiatric specialist. Family physicians have the invaluable advantage of knowing the family environment, the career and, unfortunately, often the crises of the affected bipolar people. Their function in long-term therapy and drug controls is very important.

Bipolar disorders are common and show a diverse pattern of progression called the bipolar spectrum. It is often a “roller coaster of emotions” with each individual course. Once more in the tunnel, more “saddened to death”, the other time “sky high” and at the peak of manic happiness. The ticket is often a family ticket with clustered, affective and psychotic disorders in relatives and suicides. The suicide rate is alarmingly high, at 15-20%. The ticket is usually bought early in life, often before the age of 20. The range of accompanying conditions is broad, ranging from substance addictions, panic, and anxiety to compulsions and other psychiatric disorders. Differentially, personality disorders and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are difficult to distinguish.

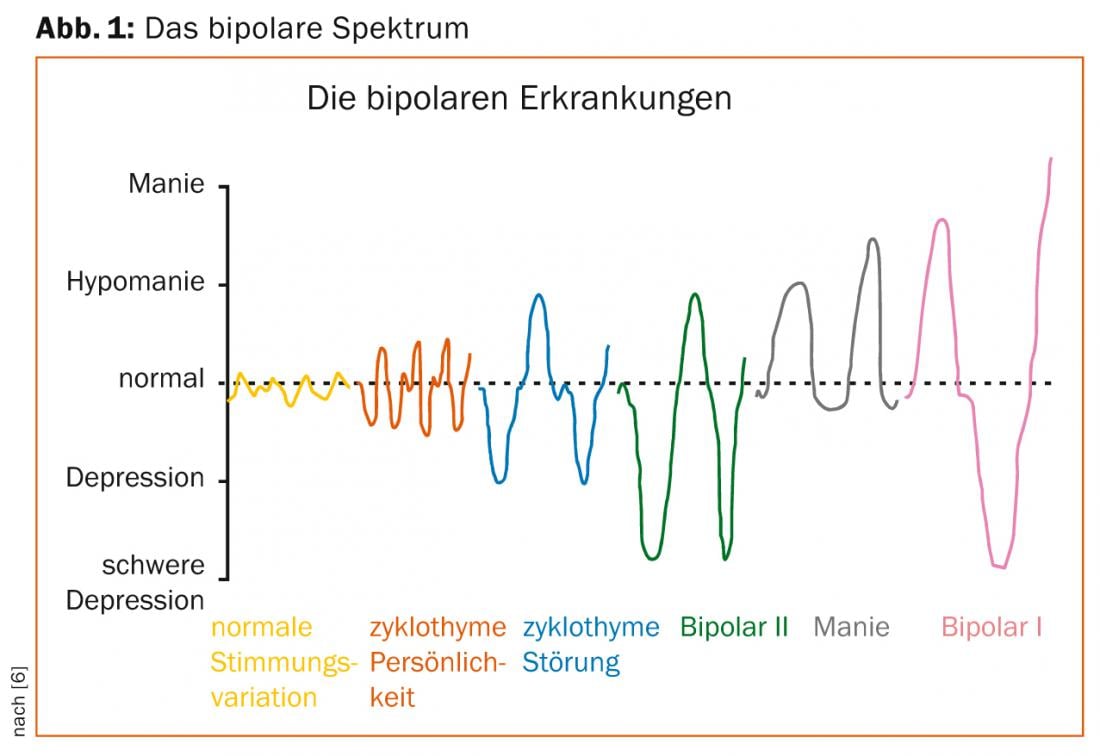

Bipolar spectrum

The bipolar spectrum (Fig. 1) ranges from mood swings that go beyond the normal-psychological or usual-to cyclothyme disorder, which is a chronic fluctuating affect disorder with excursions into hypomanic or subdepressive symptomatology. In addition, the so-called bipolar II disorder, which is characterized by the occurrence of depressive episodes and at least one hypomanic episode. The complete picture is represented by Bipolar I disorder, which includes the occurrence of manic or mixed and depressive episodes in varying degrees of severity (mild, moderate, severe).

The severity classification for mania according to ICD-10 is as follows:

- Hypomania = mild episode; ICD-10: F30.0

- Mania without psychotic symptoms = moderate manic episode (occupational and/or social functioning interrupted); ICD-10: F30.1

- Mania with psychotic symptoms = severe manic episode possibly with additional delusions (delusions of grandeur, love, relationships or persecution); ICD-10: F30.2.

Depressive symptoms dominate at doctor’s visit

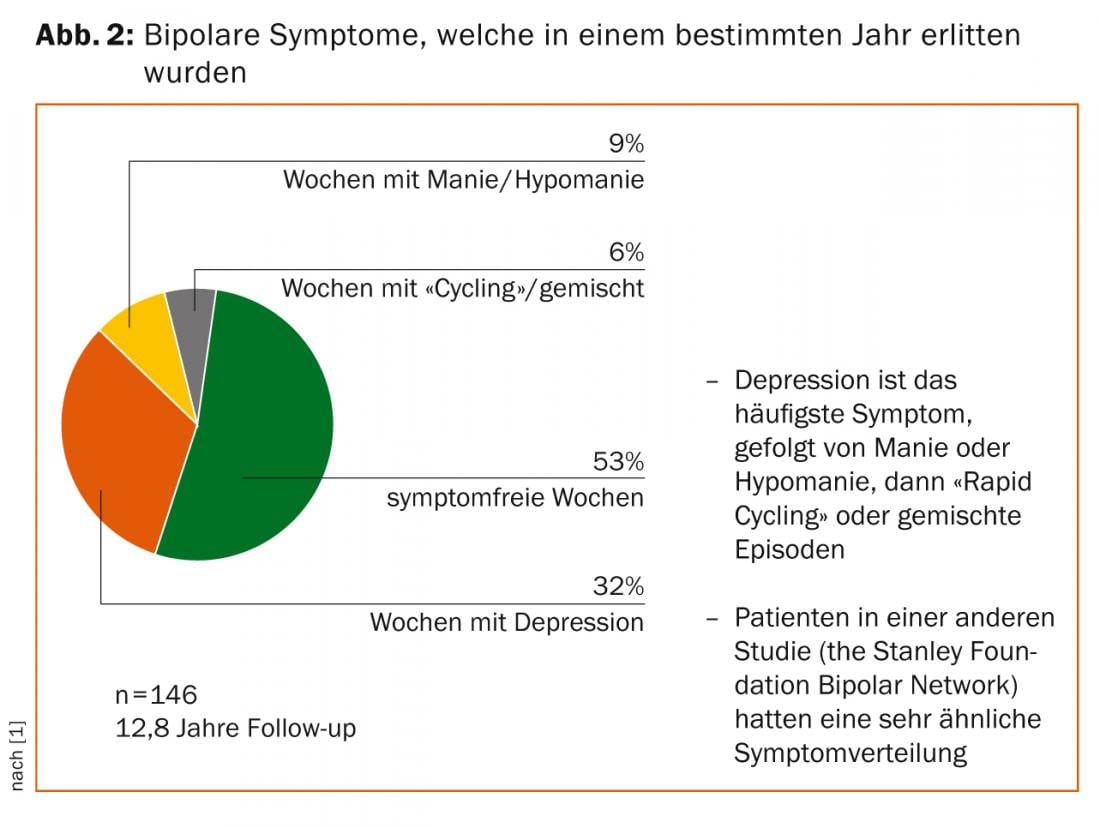

By nature, most bipolar people value the “good” times when they are hypomanic or manic (even though they may harm themselves professionally and personally in these states) more than when they are depressed and “in the hole.” In addition, affected bipolars spend much more time longitudinally in depressive states (approximately 32%) than in hypomanic or manic episodes (approximately 9%) (Fig. 2) [1].

Accordingly, these people will talk to the doctor almost exclusively about their depressive symptoms. Times when they are manic, they are less likely to respond. Thus, many bipolar people are misidentified as “depressives” with unipolar depressive disorder and are treated accordingly with antidepressants only. It is important for the diagnosis to examine affected persons closely and to question them accordingly. Hypomanic or manic symptoms must be specifically sought and queried in a non-pathologizing manner. An appropriate survey should include the following facts:

- Family history for affect disorders

- Appearance of first symptoms: exact age, first phase

- History pattern incl. Occurrence of residuals, seasonal occurrence and, at most, “rapid cycling

- Occurrence of psychotic symptoms

- Detailed medication history

- Presence of comorbidities such as personality, anxiety, dependence disorders as well as somatic diseases (diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, hypothyroidism and others more).

Special emphasis must be placed on the questions about the highs in particular. We recommend the following questions: “Are there times when you feel much better, more enterprising, more active, less fatigued, less in need of sleep than usual? Are there times when you talk more, accomplish more, do more, or travel around, for example? Have you gotten into trouble because of it? Or did others think something was wrong with you because of it?” [2].

Symptomatology of mania and depression

The leading symptoms of mania are inadequately elevated mood, increased drive, accelerated thinking, and overconfidence. Other symptoms include inappropriate cheerfulness (euphoria), hyperactivity, urge to talk, many ideas, which may increase to the point of flight of ideas, and decreased need for sleep. Typical, and unfortunately often difficult for treatment, is the absence of the feeling of illness.

The depressive states in the context of bipolar disorder are often difficult to distinguish from ordinary depression. Often, bipolar depressive moods occur more rapidly and develop into severe states with psychotic symptoms. Occasionally, they can also lighten up just as quickly or turn into hypomanic states. This corresponds to the classic manic-depressive pattern of illness described by Kraepelin as early as 1913, then summarized as manic-depressive mania. The rapid change from depressive states to manic episodes is referred to as the “switch” in the American literature. Switches may be due to the natural pattern of progression in terms of manic-depressive or depressive-manic illness; however, they may also be due to the unilateral administration of antidepressants that trigger the switch.

Treatment recommendations for bipolar disorder.

The Swiss Society for Bipolar Disorders (SGBS) has published treatment recommendations, based on German and Canadian guidelines [3]. I am happy to recommend this one. Classically, the treatment of bipolar disorder is based on four pillars [4]:

- Psychopharmacological and other biological therapies

- Psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational therapies

- Social therapeutic measures incl. Rehabilitation

- Self-help

Analogous to the three treatment phases of depression, a distinction can be made in bipolar disorders between acute treatment (until remission), maintenance therapy (approx. six months until recovery) and relapse prophylaxis (“maintenance”/possibly over years and decades). Patients’ prior experience and preferences play an important role in the selection of psychotropic drugs. The goal is to strive for both long-term stability and long-term tolerance. Accordingly, a precise treatment history is needed to find out whether previous episodes occurred under antidepressant administration or, if so, under the influence of stimulants or drugs. It is important to know whether psychotic symptoms have occurred in the past and how many affective episodes (manic and depressive) have been experienced. In addition, the severity of these episodes is critical. Based on these course parameters, it can be determined whether the course tends more toward the depressive pole, which is much more common (especially in women), or more toward the manic spectrum.

Pragmatic goals in the psychotherapy of bipolar disorder.

An important goal is to make those affected “experts on their disorder.” They should learn to know and pay attention to their individual early warning symptoms. They should learn to take a step back and strive for success even in the background. Regular medication is critical for long-term stabilization. Alcohol and drug excesses should be avoided and sufferers should get enough sleep. Not the large, but the stable and close circle of friends wants to be cultivated. Affected persons should be masters of their impulses; in the case of bipolar crises, damage limitation should be sought.

Long-term follow-up of bipolar people, apart from crisis management, can be interesting and mutually enriching for us physicians. Bipolar people, if they can accept their illness, are inquisitive and competent experts and have lived through (often painfully) a wide range of life experiences. It is these accompaniments where family physicians can make decisive contributions to the stability of bipolar people.

Drug therapy

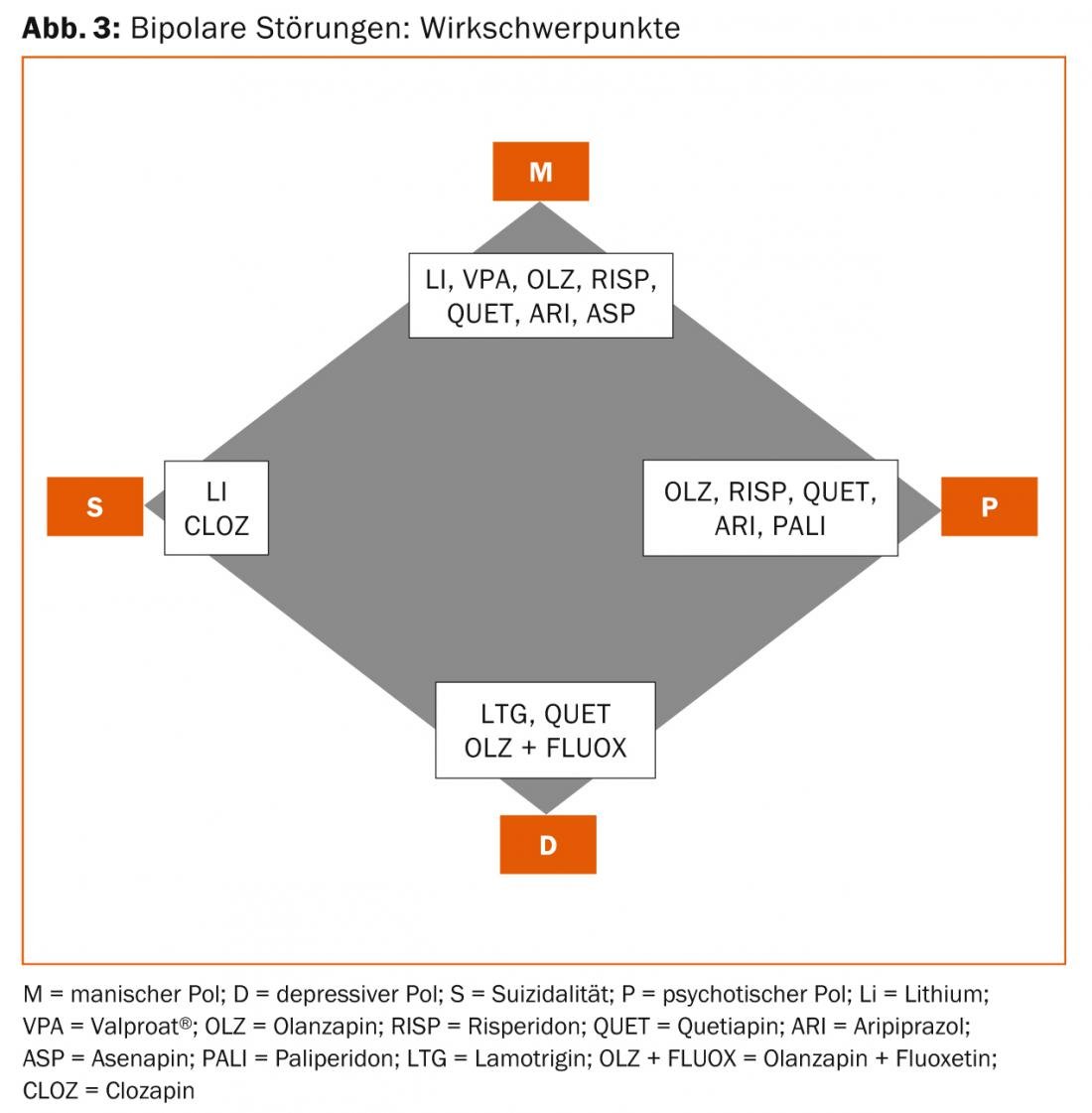

Psychopharmacologically, virtually all atypical antipsychotics, all mood stabilizers, as well as lithium and, of course, various combinations of these can be considered today. As mentioned above, which variant you choose depends on the course parameters. Basically, the four poles mania, depression, psychosis, suicidality can be distinguished. W. Greil postulated these foci of action years ago and they have been expanded and adapted to today’s indications by the author (Fig. 3).

Final tip from practice

Finally, I recommend the following procedure, which has grown out of more than 30 years of clinical experience: If there is no acute need for action (acute manic state or severe depression with suicidal tendencies), changes in medication should first be discussed in detail with the person affected and well considered. In this context, the prior experience, especially of family physicians and psychiatrists in private practice, is worth its weight in gold. Long-term mood-stabilizing therapy, e.g., with lithium, should never be discontinued without a clear indication. Conversions should be planned and implemented gradually. Combination therapies are the rule and, accordingly, possible interactions must also be taken into account. Patients should know that living with bipolar disorder can be meaningful and rewarding, even if they have gone through or will go through difficult experiences during the course. Abrupt discontinuation of the medication is dangerous.

Philipp Eich, MD

Literature:

- Judd LL, et al: The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59: 530-537.

- Anxiety J, quoted from lecture on bipolar disorder. Zurich, 2000.

- Hasler G, et al: Treatment recommendations for bipolar disorder. Switzerland Med Forum 2011; 11(18): 308-313.

- Bauer M: Therapy of bipolar disorders. In: Voderholzer U, Hohagen F: Therapy of mental illness. 9th edition, Urban & Fischer 2014.

- Angst J, et al: The HCL-32: Towards a self-assessment tool for hypomanic symptoms in outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders 2005; 88: 217-233.

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic-depressive illness. Oxford University Press 1990.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2014; 12(5): 12-16.