“We are not our genes!” With this statement, Prof. Katharina Domschke from Freiburg referred to the importance of environmental influences – and how they shape our mental health through epigenetic processes. This mechanism is particularly important in anxiety disorders and could open up new therapeutic options.

A highlight at this year’s anniversary symposium of the Swiss Society for Anxiety and Depression (SGAD) was the lecture by Prof. Dr. Dr. med. Katharina Domschke, Medical Director of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the University Hospital Freiburg (D). She drew focus to the epigenetic dimension of anxiety disorders. After all, anxiety disorders in particular are largely determined by our genes.

Frequent, burdensome and expensive

Anxiety disorders represent the most common disorders in the neuropsychiatric specialty, affecting 14% of patients across Europe. They are twice as common as unipolar depression or insomnia, which are the next largest groups in terms of frequency. Due to their high chronicity, anxiety disorders are also very expensive illnesses: After affective disorders, dementia and psychotic illnesses, anxiety disorders rank fourth in terms of cost: . This burden on sufferers, family members, and the health care system is exacerbated because anxiety disorders often result in psychological and/or somatic illnesses. Thus, anxiety disorder predisposes highly significantly to the development of a subsequent depressive episode or depressive disorder [1].

Epigenetics as an interpreter between environment and genetics

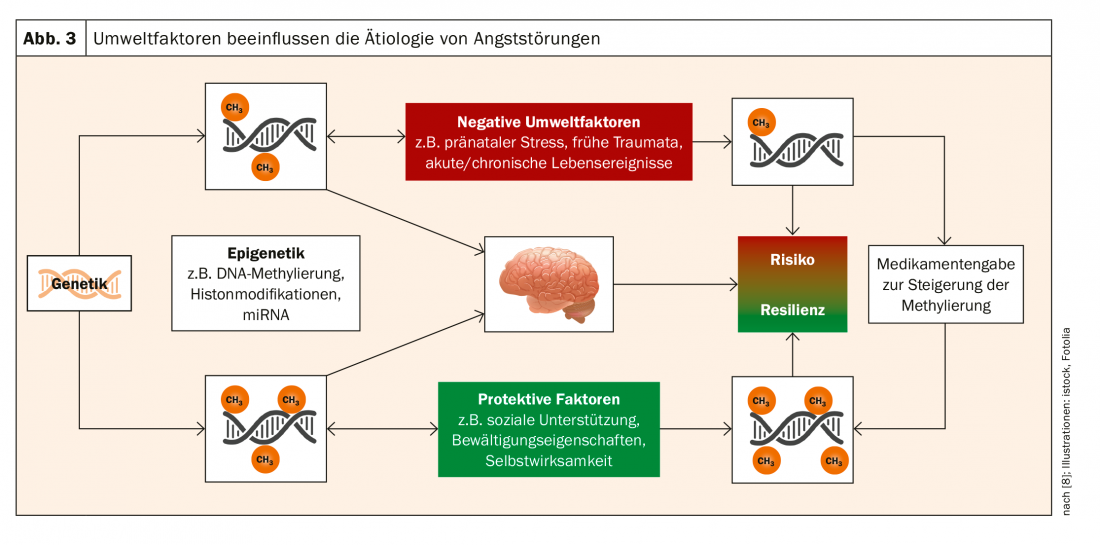

Against this background, understanding the etiology is of high importance. Anxiety disorders are polygenetic, meaning they are formed by a variety of genes. In 30-60% of all patients, there is already a genetic predisposition for an anxiety disorder. However, this disposition does not determine the form of the disease directly, but via a concatenation of factors: the alteration of nerve messenger systems and neuronal networks, certain psychophysiological settings (e.g.,CO2 sensitivity and corresponding physiological responses), and environmental factors such as noxious agents, trauma, and early childhood or prenatal events (Fig. 1).

Epigenetics plays the role of mediator between environmental factors and genetics. This is highly relevant to psychiatry, which is based on the stress vulnerability model. In this model, individual vulnerability is assumed to be determined genetically as well as by triggering environmental factors. Epigenetics takes over the “interpreter function”, so to speak, between the level of environmental factors and that of genetics. Epigenetics refers to biochemical processes that modify the function of specific genes by altering DNA and its spatial structure. “This contradicts the deterministic model,” explains Prof. Domschke. “We are indeed co-determined by our genes, but: we are not our genes!”. So genes can be changed via epigenetics – but how?

How epigenetics shapes our health

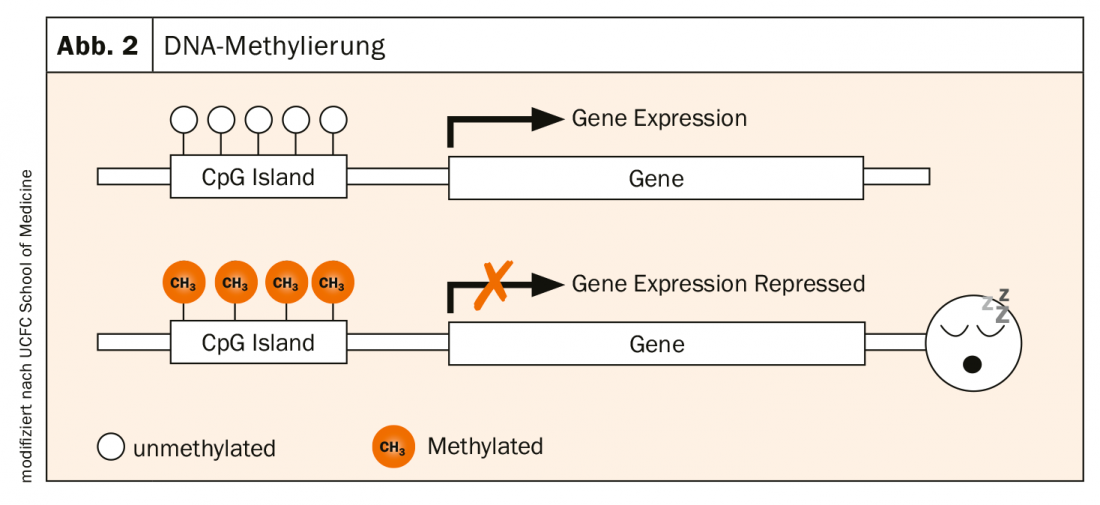

The activity of genes is determined by various processes. A very central one is DNA methylation: the enzymatic attachment of methyl groups (-CH3) to the nucleic bases (CpG islands) of DNA. This is a natural modification caused by environmental influences. CpG islands are often found in the promoter region of genes. If this region is not methylated, the gene is active and can be transcribed. If it is methylated, i.e. if a CH3 group docks there, the gene in question is no longer expressed. It “sleeps” (Fig. 2).

A risk gene for both anxiety disorders and depression is monoamine oxidase A (MAOA). It breaks down serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. The enzyme is well known from everyday practice through the use of MAO inhibitors. In a study, Prof. Domschke and colleagues were able to show that methylation of MAOA leads to reduced function of the gene – a significant finding for the therapy of diseases linked to the activity of this gene [2]. This peripheral methylation affects neuronal processes: The lower the peripheral MAOA methylation, the higher the MAOA activity in the brain. For example, Prof. Domschke and colleagues found a correlation between hypomethylation of the MAOA promoter and panic disorder [3]. Thus, MAOA methylation appears to be a biomarker for anxiety and depression.

Prof. Domschke and colleagues investigated whether epigenetics can also help predict therapy response in a study over six weeks. They compared the response to SSRI administration in patients with high MAOA methylation vs. patients with low MAOA methylation. This showed that patients with high MAOA methylation responded significantly better to SSRIs. Further studies are still needed to better understand the mechanism. But a practical implication of this finding might be that patients who have already low MAOA methylation should be treated with an SNRI or an MAOA inhibitor rather than an SSRI.

Preventing mental illness through epigenetics?

“The exciting thing, however, is not only this pathogenetic-functional mechanism, but that there is a bidirectionality,” Prof. Domschke emphasizes. “Genetics is immutable. But epigenetics, methylation, is dynamic. It responds to environmental influences.” Subjectively negative perceived life events contribute to reduced MAOA methylation. Trauma can thus lead to an epigenetic risk status. The good news in reverse: positive events correlated positively with MAOA methylation. Resilience-promoting measures can contribute to the prophylaxis of mental illness (Fig. 3).

In this context, the role of psychotherapy was also examined. Psychotherapy was also shown to normalize methylation, leading to symptomatic improvement. In the medium term, an epigenetic understanding of the mechanisms of action of psychotherapy could lead to its augmentation by drugs that raise patients with low MAOA methylation to the level of the highly methylated, Prof. Domschke said.

Overall, according to current knowledge, epigenetics represents a possibility to predict individual therapy response in the sense of personalized pharmacotherapy and – possibly – to explain mechanisms of action of psychotherapy.

What’s new in pharmacotherapy?

Specific phobias are not treated with medication, but with cognitive behavioral therapy. For social phobia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, SSRIs and SNRIs are the treatment of choice. According to a study published in 2017, agomelatine appears to be effective not only in depression, for which it is approved, but also in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder [4]. Off-label, agomelatine thus represents a good supplement. Quetiapine, approved for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, also showed significant efficacy as monotherapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder [5]. Lavender oil extract, which is indicated for anxiety and mood disorders, has also been shown in studies to be effective in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder [6].

A word about pregabalin: While this active ingredient has a clear efficacy and corresponding Ia evidence, it is suspected of being addictive. Therefore, pregabalin currently has only a B recommendation. A similar situation applies to gabapentin. However, it must be pointed out that the hazard posed by these substances is the lowest compared to other agents with dependence potential. In addition, dependence on gabapentinoids is regularly associated with other addictions, particularly opium addiction and politoxicomania. It follows that neither pregabalin nor gabapentin should be omitted from therapy – except in the treatment of already dependent patients. Rather, the administration of benzodiazepines should be avoided. The widely discussed (endo)cannabinoids currently lack sufficient evidence, so they are not a treatment option either.

Source:10th Swiss Forum for Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Literature:

- Meier SM, et al: Secondary depression in severe anxiety disorders: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. Lancet Psychiatry 2015; 2(6): 515-523.

- Ziegler C, Domschke K: Epigenetic signature of MAOA and MAOB genes in mental disorders. J Neural Transm 2018; 125(11): 1581-1588.

- Domschke K, et al: Monoamine oxidase A gene DNA hypomethylation – a risk factor for panic disorder? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2012; 15(9): 1217-1228.

- Stein DJ, et al: Efficacy and safety of agomelatine (10 or 25 mg/day) in non-depressed out-patients with generalized anxiety disorder: A 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2017; 27(5): 526-537.

- Maneeton N, et al: Quetiapine monotherapy in acute treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016; 10: 259-276.

- Kasper S, et al: Lavender oil preparation Silexan is effective in generalized anxiety disorder – a randomized, double-blind comparison to placebo and paroxetine. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014; 17(6): 859-869.

- Domschke K: Predictive factors in anxiety disorders. Neurologist 2014; 85(10): 1263-1268.

- Ziegler C, Schiele M, Domschke K: Patho- and therapy epigenetics of mental diseases. Neurologist 2018; 89: 10.1007/s00115-018-0625-y.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(3): 24-29.