Atopic eczema is a chronic recurrent skin disease based on a genetically determined dysfunction of the epidermal barrier. Every fifth to sixth child in Western civilization today is affected by this eczema condition. Effects can be chronic inflammation and excruciating itching, combined with sleep disturbances. There is a risk that growth and development will be delayed. This has social consequences for the whole family. The following article provides an overview of the causes, clinic, and treatment options in infants.

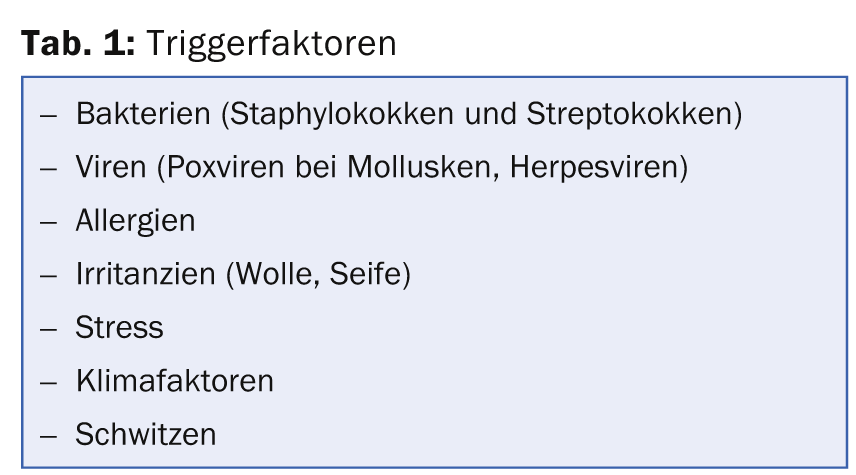

Not primarily an allergic reaction, but a genetically determined disturbance of the epidermal barrier is causally in the foreground in patients with atopic dermatitis. Filaggrin mutations are relevant to disease severity and also define the likelihood of association with allergic asthma. They lead to a skin barrier defect with increased transcutaneous allergen penetration, transepidermal water loss and consecutive dry skin. Various trigger factors can worsen eczema (Table 1).

Often trigger factors are wrongly interpreted as the cause of the eczema and parents tie the expectation of a cure to various elimination efforts, which can be seen, for example, in radical, even health-threatening diets and the rejection of vaccinations. However, it should be borne in mind that, contrary to common belief, only a relatively small proportion of affected infants have relevant food allergies (max. 20%). Thus, the role of food allergies is greatly overestimated by parents (and often by physicians). Moreover, the incidence of atopic dermatitis is the same in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. Rather, the unwarranted failure to vaccinate eczema children results in additional risk.

In principle, atopic dermatitis has a good prognosis. It heals in three-quarters of cases by the age of ten. Approximately one-third of children later develop allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and/or allergic asthma.

Clinic

Atopic dermatitis may develop in infants from initial seborrheic scalp eczema. In most cases, however, the characteristic symptoms are not found until the third month of life. A central feature is itching. On the body, trunk (excluding the diaper area) and extremity extensor side infestations are typical. The head and facial skin are most severely affected, often with weeping, bacterially superinfected cheek eczema (Figs. 1 and 2). As a variant, nummular atopic eczema may be observed in approximately 10-15% of children.

Bacterial complications are common in infancy: Colonization with Staphylococcus aureus is 90-100% (compared to 20-25% in control infants). Especially in the head area, this can cause weeping, impetiginized eczema and pyoderma. A single cycle of treatment with oral antibiotics is often very effective, especially in young children. However, it is important to implement topical anti-inflammatory therapy and antiseptic skin care simultaneously.

Eczema herpeticatum with grouped punched-out small erosions and vesicles that rapidly transform into pustules and crusts should be urgently known and recognized as a complication.

In infancy, an allergological diagnosis is useful if there is severe, persistent atopic eczema, evidence of immediate allergic type reactions such as angioedema, urticaria, vomiting, etc., or if there is failure to thrive.

How to treat?

The goal of controlling eczema for as long as possible and bringing it to healing in the course of time can be achieved with a combination of different therapeutic approaches. The guiding principle “no tolerance for eczema” is central with regard to a good prognosis with prevention of chronification of eczema, and proactive management is indicated. On the one hand, it is important to restore the epidermal barrier by means of adapted basic therapy (skin cleansing and lipid-replenishing care). In addition, prophylaxis and treatment of cutaneous superinfections by means of adapted basic therapy incl. regular skin cleansing and anti-inflammatory local therapy (antiseptics, antibiotics, corticosteroids) should be emphasized. Lastly, consistent anti-inflammatory therapy with the aim of promptly bringing eczema flare-ups to healing and preventing further flare-ups forms an important principle.

The basic therapy is adapted to the stage of eczema, localization and age of the child. Regular skin cleansing and hydration by means of daily lukewarm baths with an oil additive is of great importance, especially in infancy. By gently removing microorganisms, crusts and residues of emollients, bathing counteracts unfavorable microbial colonization of the skin, moisturizes it and improves the penetration of subsequently applied skin care products. The first ten minutes after the bath allow for improved topical absorption in the epidermis, so the products should be applied during this period. And last but not least, bathing is simply fun for many children and helps them fall asleep afterwards. In addition, if there is a tendency to bacterial superinfection, the use of an antiseptic, skin-friendly wash lotion (e.g. with triclosan) may be helpful. The moisturizing care product, especially its lipid content, should be chosen individually (rather cream base in case of weeping acute eczema). Care must be taken to ensure that it contains as few fragrances as possible, as well as few preservatives and emulsifiers. Urea-containing topical preparations should be avoided in infants because of frequent irritations (or depending on the skin type).

Fight the inflammation

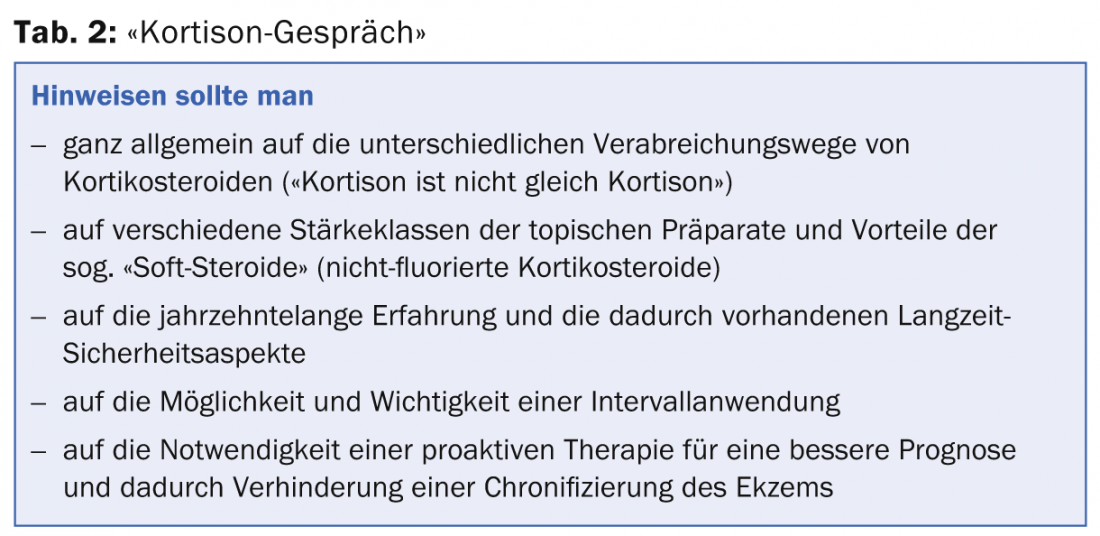

Topical corticosteroids have now been established in the local therapy of atopic dermatitis for more than five decades and can usually be used safely. Nevertheless, when prescribing these products, the “cortisone talk” with parents cannot be avoided in cases of widespread steroid phobia. It is advisable to address various aspects in this context (Tab. 2).

In principle, a single application daily is sufficient (preferably in the evening, after bathing), as the topical steroids form a depot in the stratum corneum. One should use steroids that are strong enough to deal with the eczema within five days. In young infants, dilute corticosteroids of strength class III or preparations of strength class I-II are recommended. In the acute phase, it is worthwhile to treat the patient for five consecutive days, followed by two days off, etc. If an improvement occurs, a reduction to a so-called interval therapy of e.g. two to three treatment days per week can take place (Fig. 2).

In cases with severe extensive eczema, it is worthwhile to use topical steroids under moist wraps/bandages (so-called. Wet Wraps with TubeGaze®, TubiFast Garments), the effect of which can be very impressive (Fig. 1) . The evaporation of moisture helps inflamed skin and increases hydration. In chronic cases, the involvement of a specialized caregiver or Kispex can help achieve a breakthrough.

Topical corticosteroids should not be discontinued abruptly but phased out slowly (rebound prevention). This is done by reducing the duration of application (to e.g. 2 days/week) (Fig. 2). This is a proactive therapy with the aim of preventing new eczema flare-ups without the fear of typical steroid side effects such as skin atrophy. In cases of persistent but already well-controlled eczema, this proactive therapy can also be performed with topical calcineurin inhibitors such as Protopic® ointment or Elidel® cream. Their effectiveness has been proven in children. The efficacy of Protopic® Ointment 0.1% is approximately equivalent to that of a class II corticosteroid, and that of Elidel® Cream to a class I corticosteroid. Unlike corticosteroids, collagen synthesis is not affected by these immunomodulators. Thus, there is no risk of skin atrophy even with long-term use without a break. Infections of the skin with herpes simplex viruses as well as Mollusca contagiosa or HPV mean a contraindication for Protopic® ointment or Elidel® cream.

Calcineurin inhibitors are particularly suitable for moderate eczema without microbial superinfection in regions with thinner skin (diaper area, face, eyelids) – e.g. as maintenance therapy (Fig. 2). Although not officially approved for use below 24 months of age and principally as second-line therapeutics, calcineurin inhibitors are ideal for successful long-term control and healing, particularly in persistent eyelid, cheek, and perioral eczema in infancy. Fortunately, more safety data are now available for calcineurin inhibitors, including in children. So far, not a single case of malignancy has been detected. It is still necessary to address the issue of calcineurin inhibitor safety with parents. A synergistic immunosuppressive effect of calcineurin inhibitors in combination with UV exposure should be noted, so that the preparations should be used in the evening and accompanied by adequate sun protection measures.

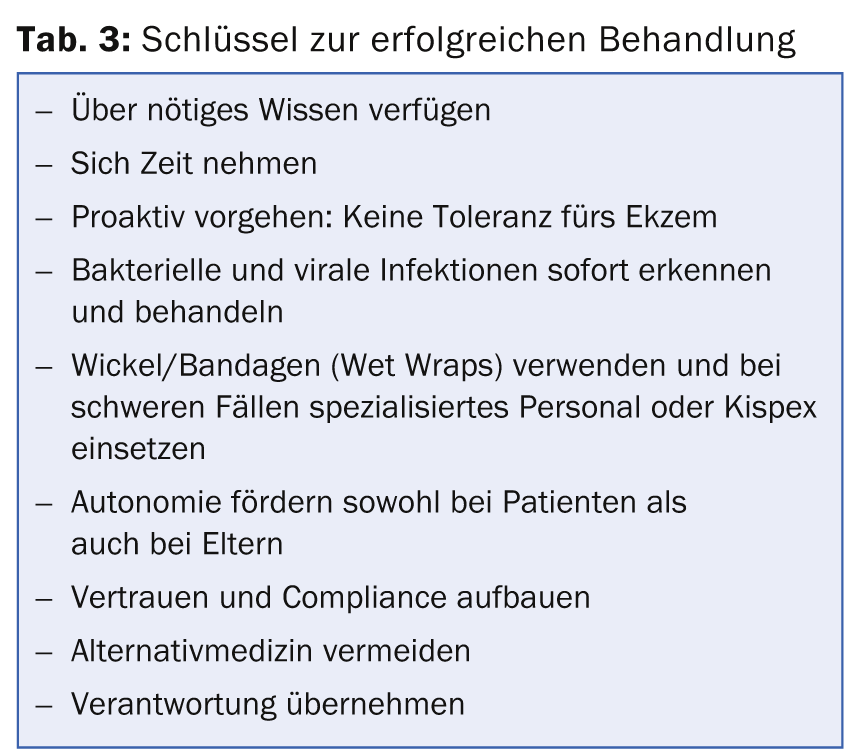

The most important rules for successful treatment in atopic dermatitis are shown in Table 3.

What to do with severe eczema and parents who prefer alternative medicine?

Point out to parents who want to forego effective therapy for a severely affected child and use only alternative medical measures the dangers of their approach. Such children may develop sleep disorders from which they may suffer for life. Children’s growth may also be impaired, and the risk for conditions such as ADHD or certain immune deficiencies increases.

Further reading:

- Höger PH: Pediatric dermatology. Differential diagnosis and therapy in children and adolescents. Stuttgart: Schattauer 2011.

- Tilles G, Wallach D, Taieb A: Topical therapy of atopicdermatitis: controversies from Hippocrates to topical immunomodulators. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56: 295-301.

- Atopic eczema in children: Management of atopic eczema sin children from birth up to the age of 12 years. NICE Clinical Guidelines, 2007.

- Luger T, Nieto A: Pimecrolimus cream 1% in infants with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis: efficacy and safety results from a 5-year randomized study. 12th World Congress of Paediatric Dermatology, 27th September 2013, Madrid.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- In persistent acute eczema (e.g., facial area), a bacterial superinfection is

- (S. aureus) is relevant and a single course of oral antibiotic therapy is effective.

- Topical corticosteroid therapy alone also reduces S. aureus colonization of the skin.

- Daily brief bathing followed by application of cream is essential for successful eczema therapy.

- Topical corticosteroids should be used proactively and continued as interval therapy (2 days/week) over time following acute treatment.

- Calcineurin inhibitors are particularly suitable in infants with already controlled eczema without superinfection in regions with thinner skin (diaper area, eye region, face) – also in the longer term to prevent recurrences.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(6): 16-22