At the Internal Medicine Update Refresher in Zurich, Christine Franzini, MD, from the Stadtspital Triemli, vividly explained the tasks that cardiac pacemakers can perform in modern medicine. She discussed the indications, provided an overview of device programming, and presented several pacing complications that are also relevant to the internist.

“The indications for a pacemaker are very diverse and can be found in detail in guidelines [1],” says Christine Franzini, MD, from the Stadtspital Triemli, by way of introduction. “In principle, pacing is indicated in higher-grade AV block and symptomatic bradycardia without reversible cause.” In asymptomatic bradycardia, a wait-and-see approach is warranted (exception higher-grade AV block).

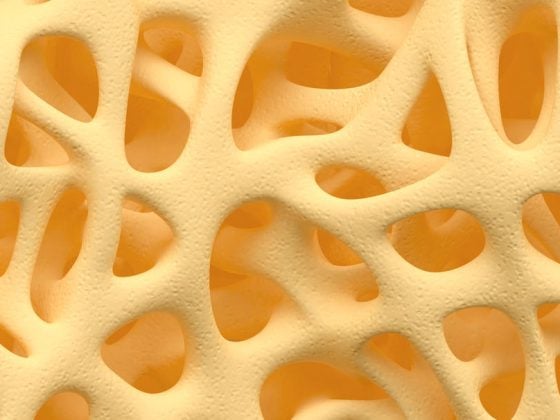

A functioning pacemaker consists of a pulse generator (battery, electronics, connectors) and electrodes (cathode and anode); it also always requires viable, healthy myocardium. In the past, there were exclusively unipolar electrodes, where the positive pole was the battery and the negative pole was the electrode tip. Today, almost only bipolar models are in use. Here, both anode and cathode are attached to the heart. The different pacemaker types can be classified according to the abbreviated pacing mode designations (Tab. 1) . The abbreviations, together with other important programming information (battery status, base frequency, maximum frequency, additional functions such as sensor and hysteresis), can be found in the so-called pacemaker ID card, which the patient ideally carries in his wallet.

Functionality and programming of the pacemaker

Very basically, the pacemaker performs two functions: It has the ability to detect an electrical signal (sensing), and it delivers sufficient energy to depolarize the myocardium (pacing). “By setting the sensitivity, we tell the pacemaker what it may and may not sense. Sensitivity, then, defines the minimum intrinsic electrical activity of the heart that is detected by the pacemaker. The lower the programmed value of sensitivity, the more sensitive the pacemaker becomes,” Dr. Franzini elaborated. Over- and undersensing must be prevented. The stimulus threshold is defined as the minimum energy required to excite the myocardium. The energy delivered by the pacemaker is fixed as output with a double safety margin.

Basic programming includes the base frequency and, for dual-chamber pacemakers, the AV/PV time and maximum frequency. Other functions depend on the company or product. The base rate is the minimum heart rate at which the pacemaker stimulates in the absence of intrinsic activity. AV time is the time between an atrial and a ventricular stimulus. PV time is the time between a sensed atrial event and a ventricular stimulus. The maximal rate includes the so-called “tracked rate,” i.e., maximal ventricular pacing in response to intrinsic activity of the atrium, and the “sensed rate,” i.e., maximal sensed pacing rate in the atrium/ventricle.

An important additional function that allows the patient’s natural frequency to fall below the basic stimulation frequency is called hysteresis. Thus, a lower frequency is programmed in addition to the basic frequency, thus preventing stimulation in physiologically bradycardic phases, e.g. during sleep. This promotes self-activity.

Complications

Especially malfunctions of pacemakers and related complications should also be known to internists. The medical history includes the date of implantation, a survey of symptoms (dyspnea, syncope, electrical stimulation symptoms, new diseases unrelated to the pacemaker), and the question of whether pacemaker control has been performed. The aforementioned pacemaker identification card already provides important information, and a 12-lead ECG and a long rhythm strip also help. Also practical for checking electrode position and continuity is an X-ray thorax pa/lateral. “If you’re still not sure, you have to interrogate the pacemaker and measure the function,” she said. Known complications are:

Twiddler syndrome (rare): Individuals who constantly rotate the unit in the pacemaker pocket cause the electrodes to unwind. This leads to dysfunction of the pacemaker. The diagnosis is made by means of X-ray. Unfortunately, surgical revision is necessary. To prevent recurrence of dysfunction, the aggregate can be sutured into the pocket.

Electrode perforation (rare, 0.1-0.8%): This complication may be acute, subacute, or chronic. In some cases, there are few or no symptoms because the puncture site is small and is auto-tamponated by the body. When symptoms do occur, they are varied and range from pericarditis, shoulder pain, skeletal muscle or diaphragmatic pacing, to dyspnea, hypotension, and hiccups. The workup can be done by device interrogation, x-ray, echocardiography, and CT scan. Surgical revision is also necessary in this case.

Electrode breakage (1-4% of electrodes): “Unfortunately, electrodes can break over time because they are exposed to multiple mechanical forces. Athletically active individuals are particularly affected,” explained Dr. Franzini. The fracture is usually localized between the clavicle and the first rib. It leads to a malfunction of the pacemaker with the known symptoms. The clarification is carried out by means of device interrogation and X-ray. Surgical revision is the only solution.

pacemaker infection (1.9% per 1000 device-years): The undisputed “worst case” of all complications is infection, with two-thirds of cases being pocket infections. Patients with diabetes mellitus, renal/cardiac insufficiency, and status post endocarditis are particularly at risk. Also favorable are a previous provisional pacemaker, a long operation time, generator change or upgrade. For example, at presentation, patients may find localized swelling, redness, fluctuation, erosion, skin adherence, and may also have pain. In addition, there may be inappetence and fatigue. Fever and systemic signs are usually absent. Diagnosis is made clinically, by laboratory/blood cultures, echocardiography (TTE/TEE) with question of endocarditis, intraoperative tissue sampling, and swabs. Only superficial infections (e.g., suture abscesses) can be treated exclusively with antibiotics for seven to ten days; all other pocket or electrode infections require removal in toto with adjuvant antibiotic therapy.

Pacemaker syndrome (up to 20%): This is a worsening of symptoms after implantation (more common with single-chamber pacemakers). The principle: The ventricular contraction initiated by the pacemaker takes place before the natural atrial contraction. Thus, the cardiac action is non-physiological, AV synchrony is absent. This results in dilatation of the atrium and jugular veins. Signs of heart failure and reflex vasodepression occur. Symptoms include fatigue, performance intolerance, cough, chest pain, and bloating. Fortunately, one-third of patients adapt rapidly and symptoms resolve, another third need an update to a dual-chamber pacemaker, and the final third fall into neither category.

MRI and pacemaker

“For a long time, MRI caused problems with pacemakers. Since 2008, however, pacemakers and electrodes suitable for MRI have been on the market,” she said. “Under certain conditions, therefore, MRIs can be performed on patients with MRI-capable equipment.” In principle, it should be said on the subject of “electromagnetic interference” that this is mainly a threat in everyday medical practice (MRI, defibrillation, electrocautery, therapeutic irradiation, lithotripsy, etc.), but rarely occurs in the everyday life of the patient.

Source: “Pacemaker. What the Internist Needs to Know”, lecture at the Update Refresher Internal Medicine, June 16-20, 2015, Zurich.

Literature:

- Brignole M, et al.: 2013 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the Task Force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Eur Heart J 2013 Aug; 34(29): 2281-2329.

GP PRACTICE 2015; 10(9): 37-39