Chronic pruritus is a multidisciplinary leading symptom associated with a high disease burden and great suffering. The updated S2k guideline provides detailed treatment recommendations for specific forms and manifestations of pruritus and emphasizes the importance of assessing the subjective distress of those affected and including it in the evaluation of the course of the disease and in the treatment.

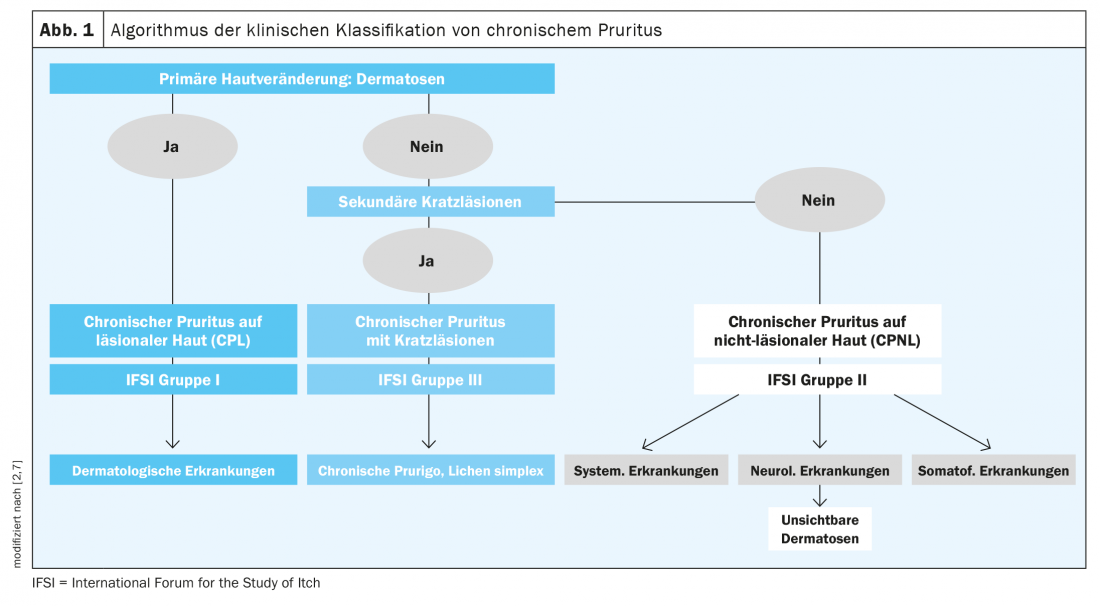

Not only dermatoses are associated with chronic pruritus: “Some people will immediately think of the skin, neurodermatitis or psoriasis when they think of itching. However, pruritus is a multidisciplinary leading symptom of numerous diseases,” explains Prof. Dr. med. Dr. h. c. Sonja Ständer, head of the “Competence Center Chronic Pruritus” at the Department of Dermatology at Münster University Hospital [1]. Chronic pruritus – that is, over at least one year. 6 weeks of persistent itching – can occur in the context of diabetes or chronic kidney disease, but also as an accompanying symptom of iron deficiency anemia or infections such as HIV or herpes zoster, as well as many other diseases.

Interdisciplinary approach is propagated

“We recommend that those affected keep a symptom diary. This is now also available in app form. The information collected in this way then makes it easier to make the right therapeutic decisions when talking to the doctor, and it is optimal for assessing the course of the disease,” adds Prof. Silke Hofmann, MD, Chief Physician at the Center for Dermatology, Allergology and Dermatosurgery at Helios University Hospital Wuppertal (D) [1]. “Pruritus is an interdisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, and it therefore makes sense to focus on the symptom of chronic pruritus regardless of the underlying disease,” emphasizes Prof. Ständer. To improve the care of patients with chronic pruritus, the guideline, which has been in place since 2005, was updated [2]. A total of 17 professional societies and organizations were involved. Patients were involved via focus groups [1]. “The implementation of the recommendations will lead to an improvement in the quality of life of patients. Above all, the multidisciplinary approach and the collaboration of experts from other professional societies will help to disseminate these important contents widely,” said Prof. Hofmann [1].

Symptom-oriented therapy: overview of the most important points

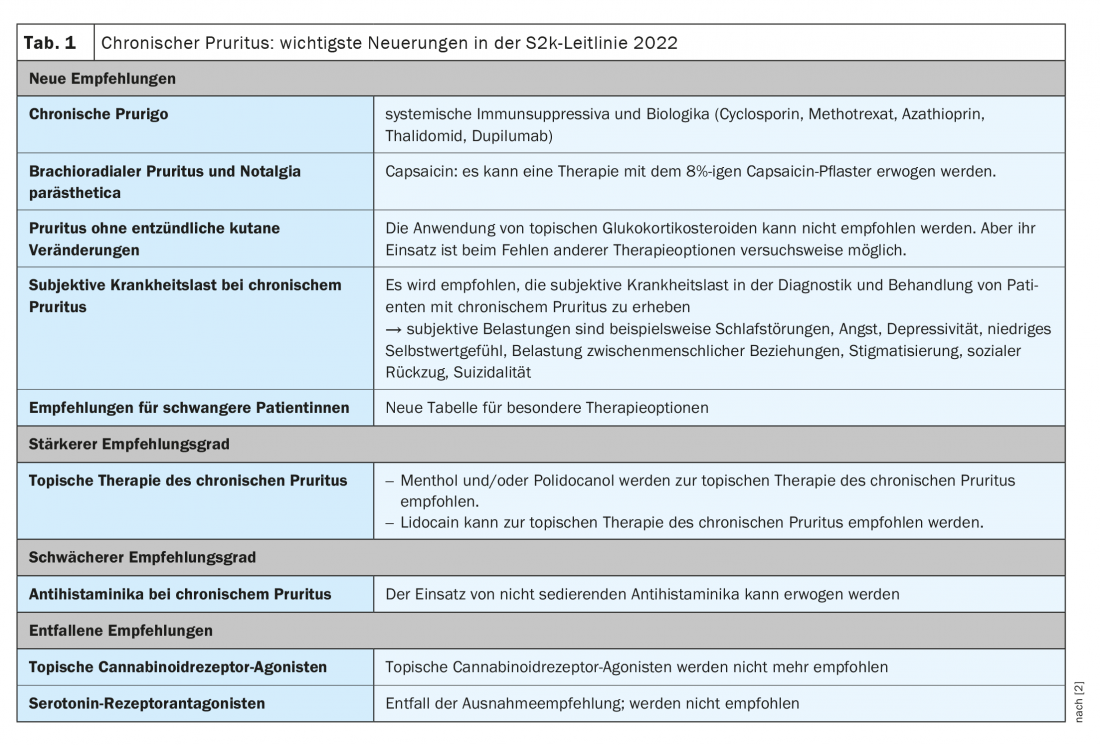

The guideline provides a comprehensive overview of evidence-based symptomatic treatment recommendations consisting of phototherapy, topical and systemic medications. Table 1 summarizes the main changes in treatment recommendations compared with the previous guideline [2]. Based on case reports and studies in prurigo nodularis, a skin condition characterized by itchy skin nodules that occur especially on the extremities, the expert group comes to some new recommendations. As a systemic immunosuppressant, cyclosporine A may be recommended for therapy in chronic nodular prurigo, and methotrexate and azathioprine may be considered as therapy. Thalidomide/lenalidomide, on the other hand, is not recommended. The biologic dupilumab may also be considered for therapy in chronic nodular prurigo (currently off-label).

It is important to note that therapy plans must be individually adapted to the problem at hand. “There is no universal, uniform therapy for chronic pruritus, as there is a high diversity of possible underlying causes and different patient collectives,” said Prof. Ständer [1].

This also applies to the strategies recommended by the guideline to break the itch-scratch cycle that is common in patients with chronic pruritus [2]:

- When itching, first apply cooling and itch-relieving lotions, creams or ointments to the skin instead of scratching it.

- Redirect the need to scratch: Instead of scratching the skin, “maltreat” the bedspread, pillow or sofa .

- Relax body and soul through autogenic training, progressive muscle relaxation or acupuncture.

Subjective patient perspective is weighted more heavily

“It is known from numerous studies that chronic pruritus is associated with considerable subjective suffering,” emphasized Prof. Ständer [1]. For many people, the itch-scratch cycle is a vicious circle that perpetuates inflammation, leads to bleeding, scabs and scars over and over again. The burden of illness on those affected manifests itself in sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and the experience of stigma. The consequences can be social withdrawal, depression or even suicidal tendencies. “The guideline explicitly recommends that patients’ subjective distress and psychological impact be assessed for diagnosis and therapy,” says Prof. Ständer [1]. In addition, there are numerous structured questionnaires that are suitable for recording findings and assessing the course of subjective complaints.

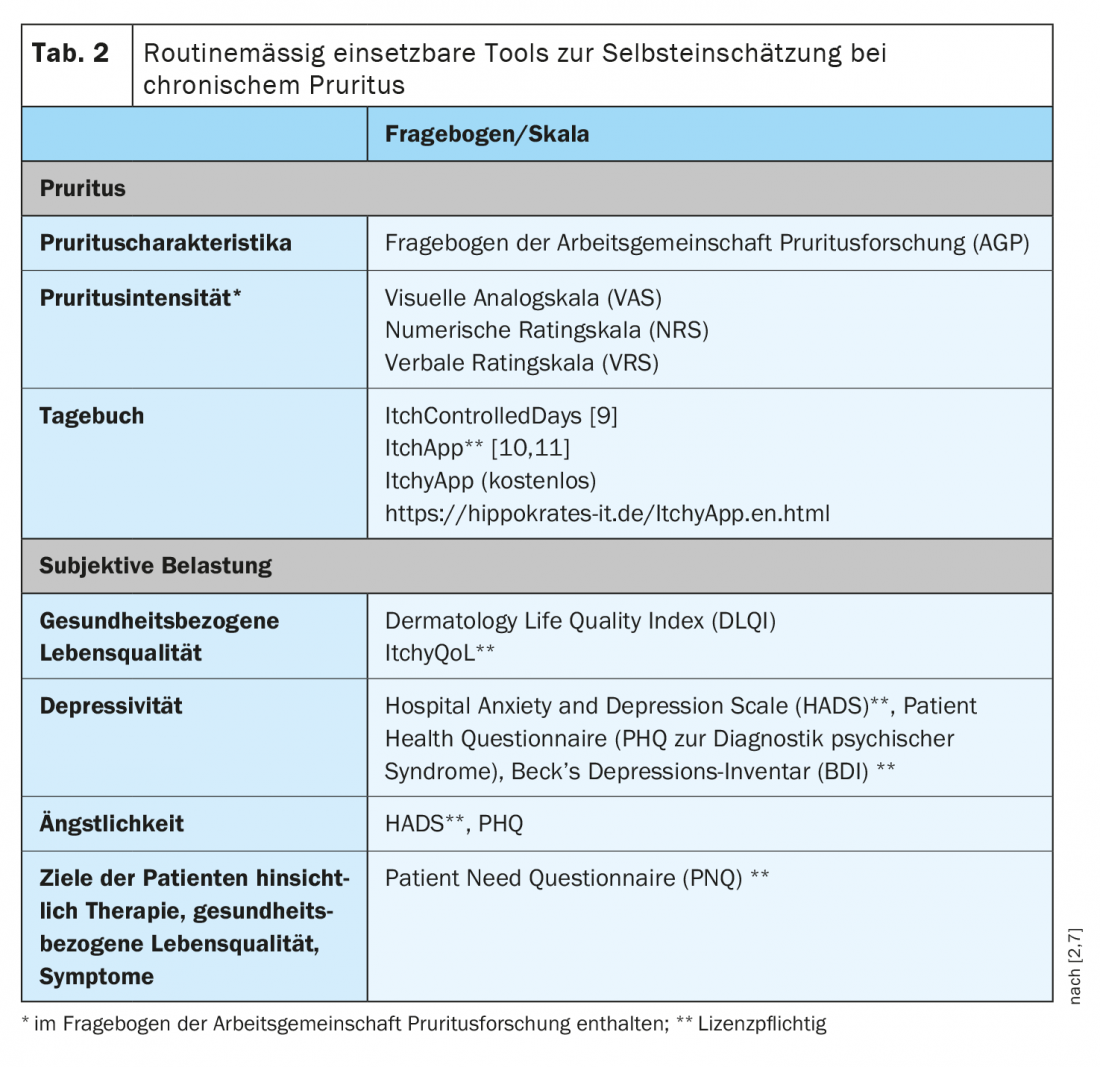

Which survey instruments to use?

The survey instruments recommended by the guideline are summarized in Table 2 [2,3]. In practice, the recording of subjective pruritus intensity has proven useful for the assessment of progression, and a visual analog scale (VAS), numerical rating scale (NRS), or verbal rating scale (VRS) is recommended for regular recording of the symptom [7]. The reminder period usually queried is 24 hours. Furthermore, it becomes difficult for those of the patients to make a reliable assessment. The average and/or most severe pruritus within this time can be queried. Assessment of health-related quality of life using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) for dermatoses or the German version of the ItchyQoL for chronic pruritus of any cause can be recommended for use in daily routine [4,5]. A recommendation is available for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) to assess the presence of anxiety and depression [6,7]. This questionnaire provides information on patient self-assessment without claiming to capture etiologic or therapeutic clues [7]. The Patient Benefit Index for Pruritus (PBI-P) questionnaire is predominantly a clinical trial instrument [7]. The first of the two pages, called the patient need questionnaire (PNQ), captures patient goals. Use of the PNQ in practice may be considered for documenting and recording patient goals prior to the initial therapy goal setting consultation. The Prurigo Activity and Severity Score (PAS) is used to objectively document the severity and extent of chronic prurigo . This is a physician’s survey form, which includes assessment of the spread, severity, number, activity, and healing of lesions [8].

Depending on the psychological effects of pruritus on subjective well-being, it may be considered to refer patients to further specialized diagnostics or treatment. In addition to offers in the context of psychosomatic primary care or special training programs, outpatient and inpatient facilities that provide psychosomatic or psychiatric care may be considered for this purpose. Existing mental comorbidities and their (pre-)treatment should always be taken into account.

Literature:

- “When itching becomes chronic, body and soul suffer: S2k guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pruritus”, Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft, 02.05.2022.

- Ständer S, et al: S2k-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie des chronischen Pruritus, 2022, AWMF-Register-Nr.: 013-048.

- Pereira MP, Ständer S: Allergology international: official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology 2017; 66 (1): 3-7.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK: Clinical and experimental dermatology 1994; 19 (3): 210-216.

- Krause K, et al: Acta dermato-venereologica 2013; 93 (5): 562-568.

- Snaith RP: Health and quality of life outcomes 2003(1): 29. DOI: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-29.

- Stand S, et al: The dermatologist; Journal of Dermatology, Venereology, and Related Disorders 2012; 63(7): 521-522; 524-531.

- Pölking J, et al: Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2018; 32(10): 1754-1760.

- Steinke S, et al: Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2018; 79(3): 457-463.e5.

- Gernart M, et al: Acta dermato-venereologica 2017; 97(5): 601-606.

- Schnitzler C, et al: Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2019; 33(2): 398-404.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2022; 32(3): 40-42