While bariatric surgery has become established for the treatment of obesity, surgical treatment of its concomitant diseases (metabolic surgery) opens up additional therapeutic options for arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, or sleep apnea syndrome, among others. Better understanding of how bariatric and metabolic surgery work will be critical to the future application of these surgical approaches to the treatment of obesity-associated comorbidities.

Morbid obesity with a BMI above 35 kg/m2 is becoming a growing socio-medical problem worldwide. Bariatric and metabolic surgery in the treatment of morbid obesity and its obesity-associated comorbidities is very effective and is considered the treatment of choice in patients after failed conservative therapy attempts due to its lasting influence on physiological, psychological, and also lifestyle influences on the patient’s weight loss.

In Switzerland, the guidelines of indications and surgical follow-up are legally regulated by the Federal Office of Public Health (www.bag.admin.ch) and the “Swiss Society for the Study of Morbid Obesity and Metabolic Disorders” (SMOB – www.smob.ch) [1].

What are obesity-associated comorbidities?

Morbid obesity is one of the responsible risk factors for chronic diseases; it is closely related to the very common obesity-associated comorbidities (Fig. 1).

Arterial hypertension: untreated hypertension and associated coronary sclerosis and myocardial infarction are common in obese patients. Since weight reduction can normalize blood pressure, it is part of the basic therapy for arterial hypertension.

Stroke: Obesity is a major risk factor for stroke (apoplexy). Larger fat deposits in the abdomen and hip area significantly increase the risk of stroke even in cases of slight overweight (BMI over 30 kg/m2).

Diabetes mellitus: Obesity is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Adult weight gain of more than 5 kg within a few years increases the incidence of developing diabetes mellitus. Almost 80% of patients with type 2 diabetes are overweight.

Sleep apnea syndrome: people who suffer from brief cessation of breathing during sleep often have a BMI above 35 kg/m

2

. A very effective treatment for sleep apnea syndrome is sustained weight loss.

Malignancies: Obesity increases the risk of certain malignancies. These include colon and prostate cancer, as well as uterine cancer.

Dyslipidemia/liver steatosis: fatty degeneration of the liver with development of hepatic fibrosis to cirrhosis can cause progressive hepatic dysfunction and is a risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis.

Osteoarthritis: Obesity favors the development of osteoarthritic joint changes, which often exacerbates already existing obesity due to the associated restriction of physical activity.

Operative procedures

All bariatric and metabolic surgical procedures involve a more or less simple anatomic transformation of the upper gastrointestinal tract in terms of reducing the available gastric volume [2]. This leads to a faster onset of satiety during food intake, which significantly limits the amount of meals (restriction). The associated physiological changes in hormonal, nervous, microbiological and gastrointestinal processes are complex and not yet fully understood in detail. Together with the associated behavioral changes in the patient’s daily routine, they bring about a significant reduction in weight and improvement in metabolic metabolism. In bypass procedures, a malabsorptive component is added to the restriction.

Sleeve gastrectomy: Nearly ten years ago, bariatric and metabolic surgery began to introduce sleeve gastrectomy as a one-step procedure because of its relative ease of performance, with only optional secondary conversion to gastric bypass (gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch – see below). This showed that patients after sleeve gastrectomy alone had a weight reduction comparable to that after gastric bypass. In the meantime, sleeve gastrectomy has become established as a one-step procedure in the treatment of morbid obesity, not least because of the supposed simplicity of the operation. However, patients show significantly more reflux symptoms in contrast to patients with gastric bypass. In this context, the achievable weight loss cannot be explained solely by a restrictive component of the tube stomach. In addition to the effect of accelerated emptying of ingested food from the gastric tube into the duodenum during sleeve gastrectomy, surprisingly, gastrointestinal hormone production after sleeve gastrectomy is comparable to that after gastric bypass without eliminating the duodenum and proximal jejunum.

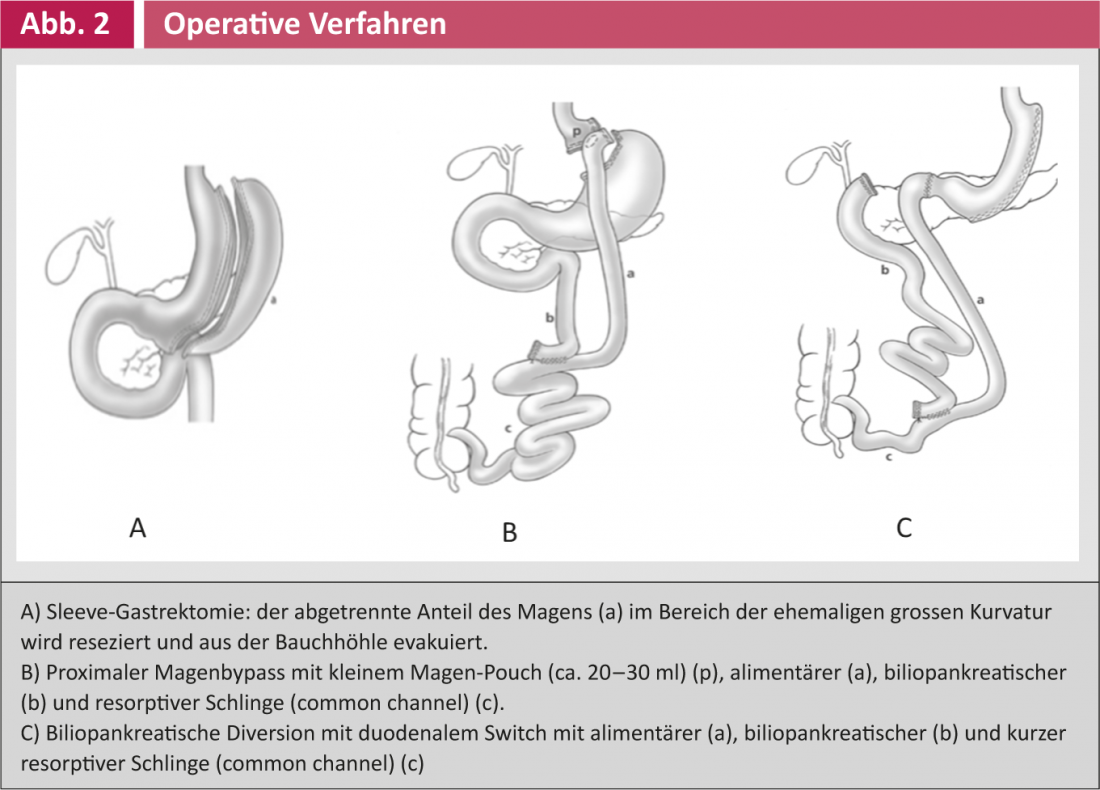

An essential dissection step in sleeve gastrectomy is the complete dissection of the large gastric curvature close to the stomach wall with transection of the gastrocolic and gastrosplenic ligaments with the vasa gastricae breves (Fig. 2).

After completion of the dissection to the left diaphragmatic thigh, stapler resection begins approximately 4-6 cm orally of the pylorus with appropriate calibration with a calibration probe (32-40 French). Salvage of the resected stomach is performed via extension of a trocar incision.

Gastric Bypass: Developed in the early 1960s from the early experience of jejuno-ileal bypass and ulcer surgery, gastric bypass is the most commonly performed of all bariatric and metabolic surgeries worldwide after the introduction of laparoscopic surgery in the 1990s. Gastric bypass (Fig. 2) involves the formation of a small (approx. 20-30 ml) gastric pouches from the subcardiac stomach. This is separated from the rest of the stomach and connected to a jejunal loop eliminated according to Roux-Y. Footpoint anastomosis is usually performed approximately 50-100 cm aborally of the ligamentum Treitz and 100-150 cm aborally of the superior anastomosis (gastrojejunostomy). In proximal gastric bypass, the length of the resorptive small intestinal tract (common channel) is usually much more than 200 cm; in distal gastric bypass, this is usually limited to approximately 120 cm.

Biliopancreatic diversion with/without duodenal switch: In the late 1970s, biliopancreatic bypass was developed as an additional method for weight reduction in morbid obesity. The aim of the operation was to induce fat malabsorption by shortening the absorptive small intestinal tract without affecting the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. Later, distal gastric resection was replaced by sleeve gastrectomy analogous to sleeve gastrectomy. During this operation, the duodenum was initially closed with a linear stapler shortly after the pylorus. Anastomosis to the ileum was performed proximal to this closure. These modifications are referred to as the duodenal switch (Fig. 2). Due to surgery-related malabsorption with consecutive deficiency states, this operation is now rarely used, and if so, only in cases of extreme obesity (BMI >60 kg/m2).

Bariatric and metabolic surgery options.

Immediate weight loss after bariatric and metabolic surgery leads to a drastic change in lifestyle habits, which sometimes also often has a positive impact on body image and self-esteem. This is often associated with a significant increase in quality of life, which is best documented in the cohort of conservatively and surgically treated obese patients established in Sweden in the early 1990s (“Swedish Obese Subjects Study”, SOS study) [3]. Just recently, the first 20-year follow-up data have been presented. These show the full range of obesity-associated comorbidities. The most important findings are briefly presented below.

Weight reduction: in the long term, weight reduction of approximately 50-75% of excess weight or an average of 30% of total weight can be expected after bariatric and metabolic surgery [3, 4]. In comparison, the SOS study clearly shows that, in contrast, patients treated conservatively are unable to further reduce their initial weight on average in the long term after a short-term therapeutic success, despite the continuation of conservative treatment measures.

As it turns out, standardized follow-up (at least 5 years) in an interdisciplinary team (obesity specialists together with nutritionists and psychologists/psychiatrists) is crucial. Nevertheless, there is a rate of “treatment failure” of about 20% of patients in the long-term course, who continuously regain weight for years after the procedure. Especially here, the aftercare must be intensive and strict – with the goal of stabilizing the weight.

Often, sustained weight loss after bariatric surgery leads to sagging and excess skin (dermatocholasis), especially in the abdomen, chest, arms, and thighs, which becomes a central problem for many patients as they progress. Consultation with a reconstructive surgeon is indicated at this time, who will help manage the patient as he or she progresses.

Long-term survival: Based on data from the earlier 1990s, the SOS study was able to demonstrate that, although surgery-related mortality was still relatively high at that time at 0.5% after bariatric and metabolic surgery, “overall” long-term survival after approximately five years had improved significantly in the group of patients who underwent surgery compared with those who received conservative therapy [4]. This is primarily related to the effective treatment of obesity-associated comorbidities. In the meantime, the perioperative risk has been further significantly reduced to date; it is now only 0.1% in some cases after bariatric and metabolic surgery.

Diabetes mellitus: As early as the early 1990s, it was observed that significant weight reduction in overweight patients with diabetes mellitus resulted in significantly better glycemic control or a reduction in the use of antidiabetic drugs, incl. diabetes medication. Insulin enables. This has also been demonstrated in the context of bariatric and metabolic surgery, even independent of weight loss, which is why these surgical interventions are now beginning to be used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus.

A recently published study prospectively compared overweight (BMI >35 kg/m2) patients with elevated HbA1c levels (>7.0%) using intensive conservative and mixed conservative/surgical approaches [5]. In the operated group, 42% (proximal gastric bypass) and 37% (sleeve gastrectomy) of patients experienced remission of diabetes mellitus at one year. This was significantly better than in the conservatively treated group (12%).

Another consideration is the prevention of diabetes mellitus in obese patients. The SOS study demonstrated that 15 years after bariatric and metabolic surgery, the incidence rate of developing diabetes mellitus was reduced from 28.4 cases/1000 patient-years in the conservatively treated group to 6.8 cases/1000 patient-years [6].

Sleep apnea syndrome: Treatment of sleep apnea syndrome usually involves nocturnal positive pressure ventilation, which can be achieved by means of an oral-nasal mask during sleep. Compliance, especially in the long-term, is correspondingly limited by sleep comfort. A two-year follow-up in bariatric and metabolic surgery patients clearly shows a significant reduction in snoring (65.5% vs. 21.6%) and sheep apnea (71.3% vs. 27.9%) compared with patients receiving conservative weight loss therapy [7].

Malignancies: Another effect of bariatric and metabolic surgery in the treatment of morbid obesity that cannot be directly explained by metabolism is seen in the incidence of malignancies over a ten-year follow-up. Thus, the incidence of operated patients with significant weight loss was significantly lower (117/2010 patients – 5.8%) than in conservatively treated patients (169/ 2037 patients – 8.3%). In which tumors a significant reduction was achieved by weight reduction cannot be inferred from the current studies, since obesity- and non-obesity-related differences exist here as well, but the overall effect is significant [8].

Conclusion

Bariatric and metabolic surgery has been the most effective and sustainable therapeutic option to achieve significant long-term weight reduction (approximately 30% of body weight) in morbid obesity. This is usually associated with a rapid improvement in obesity-associated comorbidities, which has been shown to result in significantly improved quality of life and longer life expectancy.

Literature:

- Swiss Study Group for Morbid Obesity (SMOB), www.smob.ch

- Nett PC: Bariatric and metabolic surgery. Ther Umsch 2013; 70(2): 119-122.

- Sjöström L: Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med 2013; 273(3): 219-234.

- Sjöström L, et al: Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007; 357(8): 741-752.

- Schauer PR, et al: Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(17).

- Carlsson LM, et al: Bariatric surgery and prevention of type 2 diabetes in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(8): 695-704.

- Grunstein RR, et al: Two year reduction in sleep apnea symptoms and associated diabetes incidence after weight loss in severe obesity. Sleep 2007; 30(6): 703-710.

- Sjöström L, et al: Effects of bariatric surgery on cancer incidence in obese patients in Sweden (Swedish Obese Subjects Study): a prospective, controlled intervention trial. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10(7): 653-662.