Significant progress has been made in both Alzheimer’s and Lewy body dementia in recent years. This mainly concerns the understanding of the disease and diagnostics. New substances are in advanced clinical testing.

AD and DLB are expressions of the most common neurodegenerative pathologies of older age. Both underlie the increasing deposition of misfolded proteins (AD: beta-amyloid and tau/DLB: alpha-synuclein) resulting in progressive loss of synapses and neurons and worsening cognitive impairment. With increasing age, comorbidities of both pathologies and especially combinations with cerebrovascular-related brain damage become more frequent.

In recent years, the main innovations have been in the field of diagnostics and understanding of disease. In both forms of dementia, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and ginkgo continue to be the mainstay of therapy; memantine is also available for moderate Alzheimer’s dementia. New substances with a causal approach to the disease process are in advanced clinical testing in Alzheimer’s disease.

New diagnostic systems

New diagnostic systems reflect a changing understanding of disease and promote early diagnosis.

Both DLB and AD have a biologic antecedent of pathology that accumulates over years and initially progresses without cognitive impairment that can be reliably diagnosed. Then there is a stage in which cognitive losses are neuropsychologically detectable, but lead at most to a minor impairment in everyday life in complex activities. This is well defined, especially in AD, and defined in specific diagnostic guidelines as “mild cognitive impairment due to AD” or “prodromal AD” [1,2].

If independent living is impaired, the term “dementia” is used. In common practice, it is often not until this stage that the cause is assigned.

In DSM V, the dementia term is omitted and a diagnosis of “minore” or “majore neurocognitive disorder” can be made. In both stages, an etiologic classification is made, e.g., “minore cognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease.” The basic requirement is a cognitive deterioration noticed subjectively or by a third party (relative, treating physician) and a measurable impairment in one of the following cognitive domains: complex attention, executive functions, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor skills, and social cognitions. In the case of major dysfunction, these lead to a certain lack of independence, i.e. dependence on help with complex tasks, which is not the case in minor dysfunction.

These changes promote early diagnosis by allowing disease diagnosis independent of the dementia term. Also, unlike DSM IV and ICD 10, the diagnosis can be made independent of the presence of memory impairment. This is timely because many diseases that lead to dementia do not primarily involve memory.

In current clinical practice, however, the dementia concept remains of great importance, as it is an integral part of the joint communication between patients, relatives, caregivers, insurers, neuropsychologists, and physicians, which currently cannot be dispensed with [3].

Inclusion of biomarkers in diagnostic systems

Biomarkers can increase diagnostic confidence in both AD and DLB. The publication of diagnostic systems incorporating biomarkers should facilitate their clinical application. However, there are few studies that prospectively demonstrate a benefit of biomarker use on therapeutic outcome or quality of life. This is implicitly assumed via the increase in diagnostic certainty. In addition, there are still few studies overall comparing the utility of different biomarkers with respect to specific questions [4].

The use of biomarkers therefore depends on the question in each individual case and requires the physician to have detailed knowledge with regard to the diagnostic significance of the different biomarkers and their uncertainties. Above all, it is also important to examine together with the patient what benefit can be expected from earlier and more precise diagnostics.

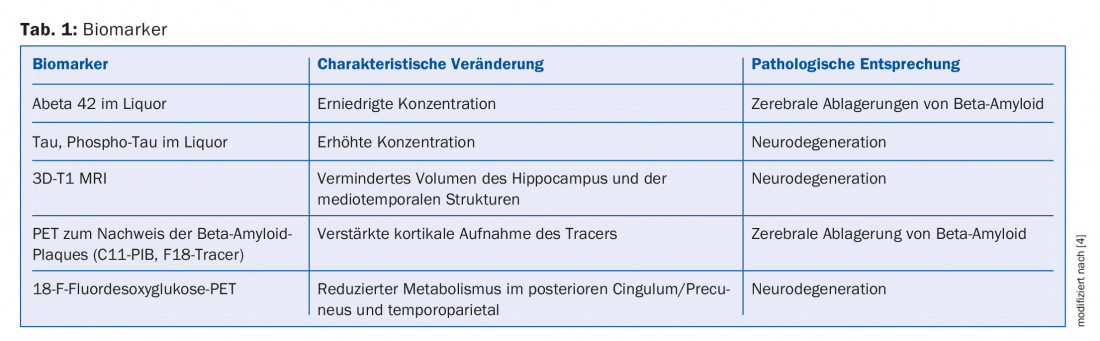

Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease (AK).

Table 1 lists the most commonly used biomarkers to support the diagnosis of AK in early and differential diagnosis [4].

Early diagnosis and patient management

AK can be diagnosed at both mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia stages with good diagnostic confidence. The optimal timing of diagnosis again depends heavily on the needs of the individual case. Careful and early exclusion of other, possibly reversible causes is crucial. Further arguments in favor of an earlier diagnosis are clear consequences for the patient’s future planning and social situation (e.g., patients still working, for whom incapacity for work would be foreseeable). Early diagnosis can serve to avoid complications through risk-minimizing measures. The spectrum here ranges from social withdrawal and bad business decisions to delirium or traffic accidents. The focus should be on the needs of the patient, who, through early diagnosis, will be able to use this knowledge to plan his or her future life. However, he should also have the option of adopting a wait-and-see observational approach if this suits him more [5]. Efficacy of drug therapy is assured in the mild AD stage.

Drug therapy for Alzheimer’s disease

In recent years, no new drugs for Alzheimer’s disease have received approval in Switzerland. Furthermore, cholinesterase inhibitors are approved for mild to moderate AD, memantine for moderate and severe AD, and Ginkgo biloba. Many studies have shown that antidementive medication has a beneficial effect on cognition and neuropsychiatric symptoms as well as on other endpoints that are highly relevant for patients and relatives. For example, the time to nursing home entry is extended. Several studies indicate a superior effect of the combination of memantine and cholinesterase inhibitors compared with monotherapy, especially in intermediate stages. However, there is no obligation to pay benefits by the health insurance companies in this respect [6].

Clinical studies

Currently, compounds with clear biological activity targeting beta-amyloid are in advanced clinical testing (Phase III). Beta-secretase inhibitors decrease new beta-amyloid formation; strategies involving the administration of antibodies to beta-amyloid attempt to reduce beta-amyloid in the brain. For example, in a phase Ib study, the antibody aducanumab produced a dose-dependent reduction in beta-amyloid plaques in the brain after administration for approximately one year. This was also accompanied by a slowing of clinical deterioration [7]. The target groups of such studies are currently predominantly patients with mild AD or mild cognitive impairment due to AD, as it is suspected that the compounds have better efficacy at earlier stages. The hope is that a new effective therapeutic approach will then be available here in the foreseeable future. In addition, the first large studies are also being undertaken with participants without cognitive impairment but with biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease [8].

New diagnostic criteria of DLB

DLB tends to be underdiagnosed and often an AD diagnosis is made instead. This is despite the fact that there are clear differences in the clinical symptoms and the expected difficulties in the course of the disease.

To remedy this, DLB diagnostic criteria were implemented and a new revision was published in 2017. The basic prerequisite for a diagnosis of DLB is cognitive decline leading to impaired performance in social life and work or in coping with daily life. Unlike AD, there are not yet specific criteria for early diagnosis.

The core clinical criteria are fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, and Parkinson’s-like movement disorders. REM sleep behavior disorder is now also included among the core criteria.

Fluctuating cognition may manifest itself, for example, in periods of drowsiness, staring ahead, or incoherent speech, while in other periods there is cognitive clarity. The visual hallucinations are typically fleshed out and often have people or animals as their content. Movement disorders often include only one of the characteristic Parkinson’s symptoms of rigor, bradykinesia, or tremor. The hallmark of REM sleep behavior disorder is the acting out of dream content that is often escape or attack in nature. This due to a lack of muscle atonia during this sleep phase. The severity of REM sleep disorder may change and even attenuate over the long-term.

If two of these core symptoms are present, a diagnosis of probable DLB can be made. Strongly suggestive biomarkers of DLB include evidence of reduced dopamine transporter binding of specific PET or SPECT tracers in the striatum or reduced postganglionic sympathetic innervation of the heart (cardiac scintigraphy with metaiodobenzylguanidine). Polysomnographic evidence of absent atonia in REM sleep is also an indicative biomarker. If one is present, the combination with one of the core symptoms is sufficient to diagnose probable DLB.

Critical to the course of the disease are common clinical features of DLB, although these are nonspecific. In particular, a strong sensitivity to antidopaminergic substances, instability in posture, falls, signs of autonomic dysfunction e.g. constipation, incontinence or orthostatic hypotension should be mentioned [9].

Drug therapy of DLB

Drug therapy is very complex and is strongly geared to the symptoms. The clearest evidence is for the use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, with evidence of improvement in cognition and level of function in daily life and delay in disease progression. Neuropsychiatric symptoms such as visual hallucinations, delusional phenomena, or apathy may also improve with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Antidopaminergic substances must be avoided. In the treatment of movement disorders, it should be noted that L-dopa tends to have a worse effect than in Parkinson’s disease and may lead to worsening of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Therefore, the principle “start low, go slow” is particularly recommended here. Due to the complex drug therapy and the multifaceted possible symptoms, close therapeutic management with the involvement of relatives or other helpers is highly recommended [9].

Literature:

- Dubois B, et al: Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. The Lancet Neurology 2014; 13(6): 614-629.

- Albert MS, et al: The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2011; 7(3): 270-279.

- Maier W, Barnikol UB: [Neurocognitive disorders in DSM-5: Pervasive changes in the diagnostics of dementia]. The Neurologist 2014 May; 85(5): 564-570.

- Frisoni GB, et al: Biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in clinical practice: an Italian intersocietal roadmap. Neurobiology of aging 2017; 52: 119-131.

- Gietl AF, Innocence PG: [Screening and prevention of cognitive disorder in the elderly]. Revue medicale suisse 2015; 11(491): 1944-1948.

- Kressig RW: [Dementia of the Alzheimer type: non-drug and drug therapy]. Ther Umsch 2015; 72(4): 233-238.

- Sevigny J, et al: The antibody aducanumab reduces Abeta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2016; 537(7618): 50-56.

- Aisen P, et al: EU/US/CTAD Task Force: Lessons Learned from Recent and Current Alzheimer’s Prevention Trials. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2017; 4(2): 116-124.

- McKeith IG, et al: Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2017; 89(1): 88-100.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(2): 23-27