At the SGIM Congress in Basel, Prof. Roland von Känel, MD, Head of Psychosomatic Medicine, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the Barmelweid Clinic, gave an update on the relationship between stress, depression and heart disease. It turned out that psychological problems are not only important risk factors for an infarction, but are also inversely caused by the traumatic experience of an infarction actually taking place. Such depression and post-traumatic stress disorder pose a challenge in practice – not least because they require different diagnostic and therapeutic strategies than the classic forms of these disorders.

“Emotional triggers for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are common and thus clinically relevant,” Prof. Roland von Känel, MD, Chief of Psychosomatic Medicine, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Barmelweid Clinic, introduced his presentation. Psychosocial risk factors such as acute emotional stress, chronic social stress, negative affect, certain personality factors, and fatigue states show comparable increases in risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) as established parameters (e.g., smoking, diabetes, obesity, lack of activity). Studies particularly support the evidenced role of stress: anger outbursts cause a nearly fivefold increase in risk of myocardial infarction/ACS according to a meta-analysis [1] (incidence rate ratio 4.74; 95% CI 2.50-8.99). The critical time interval is two hours after an outburst of anger. Apparently, there is also a dose-effect relationship: the more trouble, the higher the danger. In contrast, regular aspirin and beta-blocker use reduced the risk of ACS.

Even after such an event, patients are not immune to negative effects of stress: stress-induced platelet activation is significantly higher in individuals who had experienced an ACS with a (negative) emotional trigger event 2 hours before symptom onset approximately 1 year ago than in those with occurred ACS without emotional triggers. Platelet recovery time is also prolonged [2].

Modulators that reduce stress-induced hypercoagulability include dietary flavanoids, nonselective beta-blockers, aspirin, calcium antagonists, positive emotions, and melatonin. Flavanoid-rich dark chocolate was shown to significantly lower stress-induced fibrin formation (D-dimer) in a healthy population compared with placebo chocolate [3]. The same is true for 3 mg oral melatonin one hour before the standardized stress test [4].

Chronic stressors as psychosocial risk factors for myocardial infarction.

A major chronic stressor is workplace stress. It increases the risk of CHD by approximately 23% [5] and remains dangerous even after infarction: László et al. found a 73 percent increase in risk for the combined endpoint consisting of nonfatal myocardial infarction and cardiac mortality and a 65 percent increase in all-cause mortality [6]. Furthermore, the lack of functional and structural social support is relevant for patients with pre-existing CHD: meta-analyses suggest a 1.4-1.7-fold increase in mortality risk [7].

The heart attack as a stressor

20% of patients feel very stressed during the infarction and have great fear of death. Another 50% report moderate-severe stress and fear of death. Approximately 10-15% develop post-traumatic symptoms of clinically relevant magnitude (post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD) in the months thereafter [8]. “These factors, in turn, increase the risk of hospital readmission due to a cardiovascular event,” Prof. von Känel said. According to Edmondson et al. the risk of poor prognosis (mortality and/or ACS recurrence) even doubles [8]. “Also not to be forgotten: In the partner, stress experience, anxiety and depressive moods are sometimes more pronounced than in the infarct patient himself.”

Depression news

Major depression is common in infarct patients (19.8%). Clinically relevant symptoms are found in approximately 7-31% [9]. Depression is also a relevant risk factor for poor prognosis after myocardial infarction, with an approximately twofold increase in all-cause mortality risk and an almost threefold increase in cardiac mortality risk.

“According to DSM-IV/V, depression is a heterogeneous complex of different symptoms, the most important of which are depressed mood and decreased interest or pleasure in activities,” the speaker said. In the pathogenesis of depression in the myocardial infarction patient, infarct experience and inflammation play an important role. According to various studies, these two parameters interact in the formation of depressive symptoms. For example, fear of death during infarction correlates positively with TNF-α at hospital admission and with depressiveness one week and three months afterward. Because of these specific conditions, “cardiac depression” should be distinguished from “psychiatric” depression and probably treated differently.

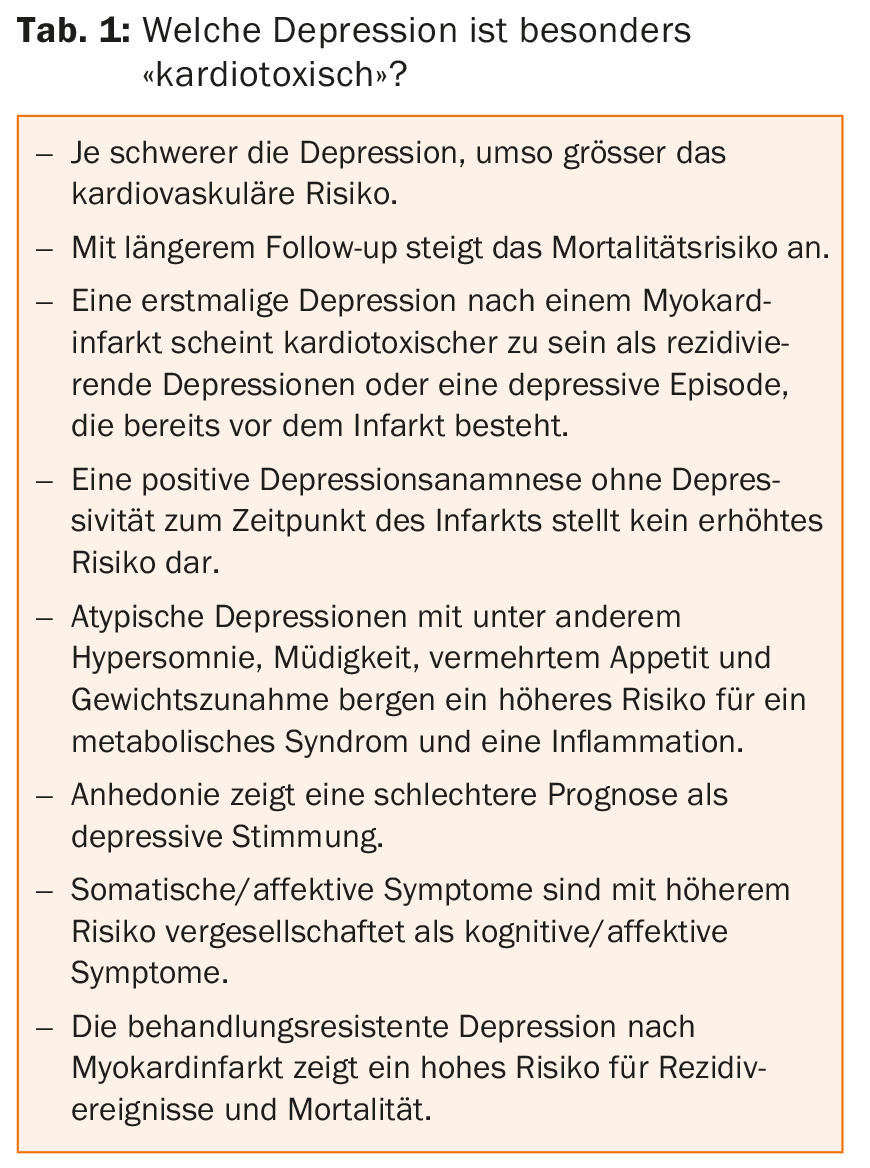

If depression were divided into cardiotoxic dimensions (Table 1) and therapies or new models of care were derived from them, prognosis could be improved.

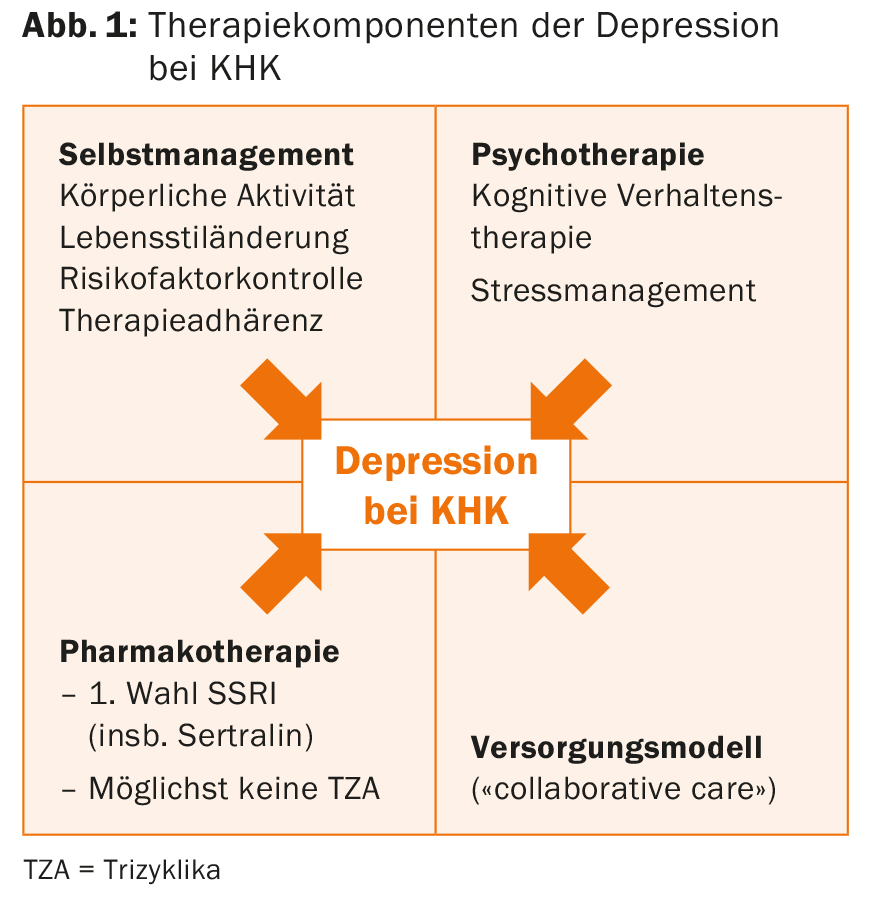

Preventive approaches to reducing traumatic infarct experience have potential in this regard [10]. In principle, the following therapeutic components are part of antidepressant treatment in CHD: self-management, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and integrated team-based care models (Fig. 1).

It should be remembered that SSRIs, although the first choice in pharmacotherapy, also have their pitfalls. For example, bleeding tendency is increased with antiplatelet agents [11]. Furthermore, interactions with other drugs have to be considered (SSRI inhibit CYP450 enzymes) and regarding citalopram there is the question of QTc interval prolongation at a dose >40 mg/d [12].

Source: “Stress, Depression and Coronary Artery Disease – An Update,” presentation at SGIM Congress, May 20-22, 2015, Basel.

Literature:

- Mostofsky E, Penner EA, Mittleman MA: Outbursts of anger as a trigger of acute cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2014 Jun 1; 35(21): 1404-1410.

- Strike PC, et al: Pathophysiological processes underlying emotional triggering of acute cardiac events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006 Mar 14; 103(11): 4322-4327.

- von Känel R, et al: Effects of dark chocolate consumption on the prothrombotic response to acute psychosocial stress in healthy men. Thromb Haemost 2014 Dec; 112(6): 1151-1158.

- Wirtz PH, et al: Effect of oral melatonin on the procoagulant response to acute psychosocial stress in healthy men: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Pineal Res 2008 May; 44(4): 358-365.

- Kivimäki M, et al: Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2012 Oct 27; 380(9852): 1491-1497.

- László KD, et al: Job strain predicts recurrent events after a first acute myocardial infarction: the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. J Intern Med 2010 Jun; 267(6): 599-611.

- Barth J, Schneider S, von Känel R: Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2010 Apr; 72(3): 229-238.

- Edmondson D, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence and risk of recurrence in acute coronary syndrome patients: a meta-analytic review. PLoS One 2012; 7(6): e38915.

- Thombs BD, et al: Prevalence of depression in survivors of acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med 2006 Jan; 21(1): 30-38.

- Meister R, et al: Myocardial Infarction – Stress PRevention INTervention (MI-SPRINT) to reduce the incidence of posttraumatic stress after acute myocardial infarction through trauma-focused psychological counseling: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013 Oct 11; 14: 329.

- Labos C, et al: Risk of bleeding associated with combined use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and antiplatelet therapy following acute myocardial infarction. CMAJ 2011 Nov 8; 183(16): 1835-1843.

- Vieweg WV, et al: Citalopram, QTc interval prolongation, and torsade de pointes. How should we apply the recent FDA ruling? Am J Med 2012 Sep; 125(9): 859-868.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(4): 34-36.