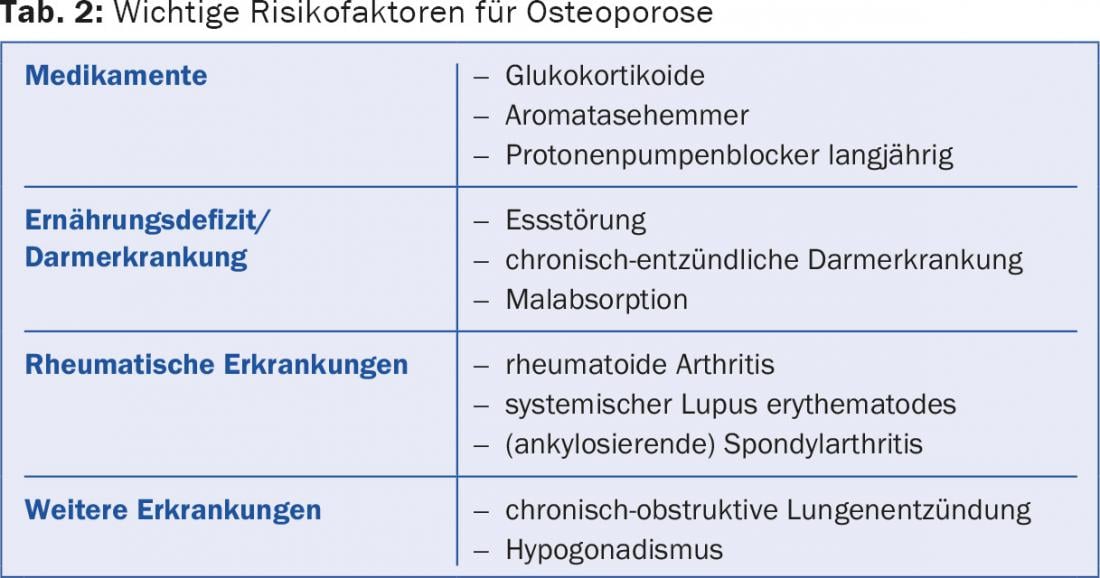

There is currently insufficient evidence to support calcium substitution in the healthy general population for primary prevention of osteoporosis. Although a small increase in bone density was measured densitometrically, no clinically relevant effect in the general population is likely to be derived from this [1]. On the other hand, the recommendation of sufficient calcium and vitamin D intake (Tab. 1) as a basis for any osteoporosis therapy and as primary prophylaxis of osteoporosis in risk groups (Tab. 2) undisputed. Here, too, calcium intake should primarily come from food.

Calcium and vitamin D are essential for bones. Without them, the formation and maintenance of the bone structure is not possible. It was shown many years ago that calcium (1.2 g/d) and vitamin D (800 IU/d) supplementation can significantly reduce the likelihood of hip, vertebral, and other fractures in older, institutionalized, postmenopausal women [2].

Vitamin D

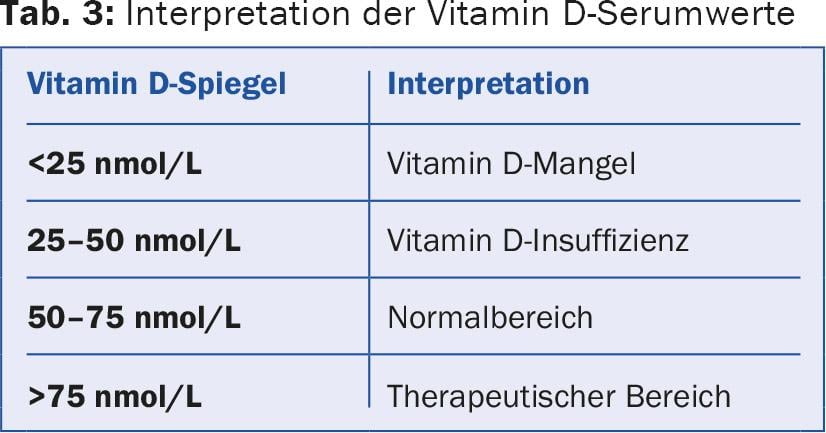

On the one hand, vitamin D is formed in the skin under UV radiation, on the other hand, it is also absorbed with various foods such as fish, meat and dairy products. Internationally, a serum level of >50 nmol/L is considered adequate and a serum level of <20 nmol/L is considered deficient (Table 3) [3]. Severe vitamin D deficiency leads to bone structure loss via secondary hyperparathyroidism, and this in turn leads to an increased fracture tendency.

In many people over the age of 65, a deficiency of vitamin D can be detected by laboratory tests. The vitamin D synthesis capacity of aging skin decreases because the cutaneous 7-dehydrocholesterol concentration of a 70-year-old is only 25% of that of a 20-year-old. Even in young people, vitamin D synthesis in our latitudes is actually only sufficient in the sunny summer months, and only with pale skin without sunscreen.

Vitamin D substitution demonstrated a reduction in hip and non-vertebral fractures. However, this reached statistical significance only in the high-dose groups (>800 IU/d) [4].

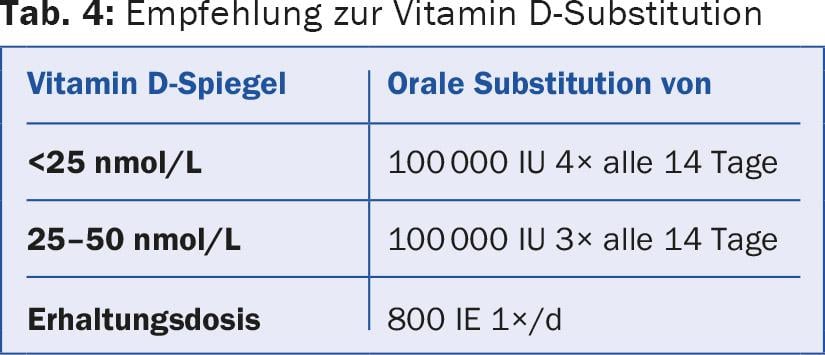

The level should be determined before starting vitamin D substitution and during the course (Tab. 4) [3]. Vitamin D substitution is generally considered safe and is now predominantly performed perorally, whether with daily, weekly, or monthly drop doses. Toxicity is not expected until serum levels reach >150 nmol/L. Symptoms of overdose include nausea, vomiting, constipation, sensory disturbances, weight loss, and kidney stones or calcium deposits in other organs.

Calcium

Recommendations for daily calcium intake are currently in flux. Currently, the Swiss Association against Osteoporosis (SVGO) recommends a daily intake of 1000-1200 mg calcium. Ideally, calcium should be taken in with food, as this ensures a steady supply throughout the day. Calcium is found in milk and dairy products as well as in vegetables, cereals and mineral water. Various calculation tables are available online for calculating daily dietary calcium intake (e.g. calcium calculator at www.rheumaliga.ch).

Under different circumstances and in different diseases, the enteral absorption of calcium and vitamin D is reduced. In such cases, the diagnosis of the underlying disease (e.g., enteropathy) must be made first. In addition, risk factors should be eliminated if possible ( Tab. 2) . Special mention should be made of the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI). Gastric acid is critical for calcium homeostasis. Long-term PPI therapy not only decreases bone mineral density, but has been shown to increase fracture risk.

The body compensates for too low calcium intake in the longer term with secondary hyperparathyroidism, which is also the pathogenetic process in PPI use. This leads to calcium resorption from the bones, and consequently to a decrease in bone density and finally to an increase in the probability of fractures. These groups of people benefit from regular calcium substitution, as do people on glucocorticoid therapy.

Dietary calcium does not increase cardiovascular risk [5]. Some studies even described a minimal protective effect. In contrast, the results with regard to calcium supplementation are not consistent, which is probably due to the different study design, the different study populations, and their regional dietary habits. Overall, populations with low dietary calcium intake and low vitamin D levels benefit the most. Conversely, patient groups with calcium supplementation are more likely to have increased cardiovascular risk, whereas this has not been demonstrated for high dietary calcium.

One potential side effect is nephrocalcinosis. As a primary endpoint, this has not been studied to date, and most studies do not mention kidney stones. A single paper reports the incidence as 2.3% in the calcium group compared with 1.9% in the placebo group [6]. Gastrointestinal complaints are also assessed differently. These range from mild constipation to acute colic that can lead to hospitalization. Again, there is little data on incidence.

Benefits for the general population

It remains undisputed that adequate calcium intake combined with vitamin D can reduce the incidence of fractures in the elderly and institutionalized. This effect is stronger the higher the deficiency of vitamin D or calcium intake. It is much less pronounced in the healthy general population. Six large randomized trials showed at most a slight increase in bone density (without statistical significance). The authors conclude that the small beneficial effect does not justify the costs and possible side effects [7].

Literature:

- Tai V, et al: Calcium intake and bone mineral density: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015; 351: h4183.

- Chapuy M, et al: Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 1637-1642.

- Rizzoli R, et al: Vitamin D supplementation in elderly or postmenopausal women: a 2013 update of the 2008 recommendations from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Curr Med Res Opin 2013; 29(4): 305-313.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 40-49.

- Waldmann T, et al: Calcium and cardiovascular disease: a review. Am J Lifestyle Med 2015: 9(4): 298-307.

- Jackson R, et al: Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation on the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:669-683.

- Bolland MJ, et al: Calcium intake and risk of fracture: systematic review. BMJ 2015; 351: h4580.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(12): 15-17