PPIs are very effective and largely safe medications. A prescription must be well justified, especially for long-term therapy. For long-term therapy, the lowest effective dose should be used. If rebound symptoms occur, the second discontinuation attempt should be made by slowly tapering off over several weeks.

The introduction of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to the market nearly 30 years ago revolutionized the treatment of gastroduodenal ulcers and gastroesophageal reflux disease. In the meantime, the preparations are among the most frequently prescribed drugs. They are highly effective and mostly well tolerated. However, excessive use and incorrect indication (both in primary care and in hospitals) lead to high health care costs and there is also increasing evidence of possible long-term side effects [1]. Certain preparations are now available over the counter and are skillfully marketed, so that a further increase in the use of these PPIs can be expected even without proper indication.

Mechanism of action and optimal administration

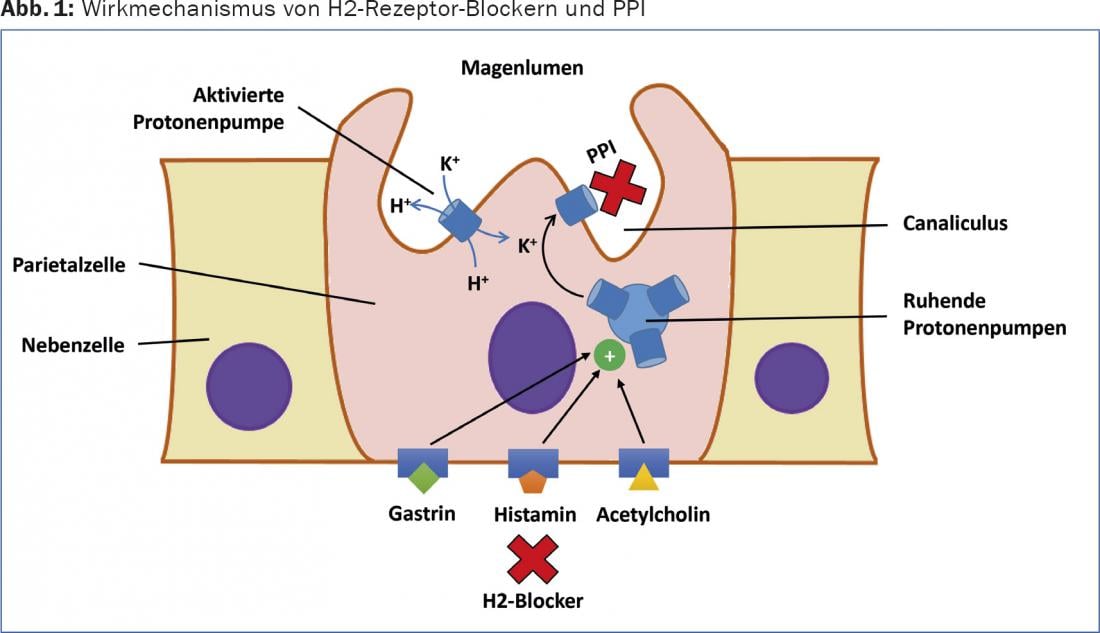

Acid secretion in the stomach is stimulated by endocrine, paracrine and neuronal modulators, including acetylcholine (vagus nerve), gastrin and histamine (Fig. 1) . Gastrin, which is released after gastric distension, not only directly stimulates acid secretion but also contributes significantly to the release of histamine from ECL cells. Histamine, in turn, causes increased acid secretion by binding to the H2 receptor. This explains the good efficacy of the specific H2 receptor blockers in principle, but this is limited in time by the interactions and redundancy of the different activation pathways. Direct inhibition of apical/luminal proton pumps of parietal cells (H+-K+-ATPase) can efficiently inhibit acid secretion for a long time if the medication is administered correctly [2].

PPIs are pro-drugs that accumulate in the acidic secretory channel system of stimulated parietal cells, where they theoretically reach a concentration 1000-fold higher than in blood at pH 1. In the channel system of the voucher cell, the substances are converted into the active metabolites, where they exert their effect by covalent binding to the proton pump. PPIs bind only to activated proton pumps and accordingly act most efficiently on parietal cells in the postprandial secretory phase. Food intake increases acid secretion and thus the proportion of active proton pumps. Therefore, due to the very short half-life, relatively early peak plasma level (1-2 hours after ingestion), and reduced postprandial absorption, PPIs should be taken approximately half an hour before eating for optimal effect.

H2 receptor blockers should not be administered concomitantly with PPIs because they potentially limit their efficacy. Animal studies indicate that concomitant administration of H2 receptor antagonists and a PPI can greatly reduce the acid inhibitory effect of the PPI. The H2 receptor antagonist reaches the vestibular cell before the PPI and reduces the acid concentration in the secretory canal system. However, PPIs are theoretically reduced in their acid-inhibiting effect by 90% even when the pH is raised from 1 to 2. If both drugs must be administered together, the optimal timing of the two administrations is not clear. Typically, H2 receptor blockers are administered just before bedtime for nocturnal symptoms.

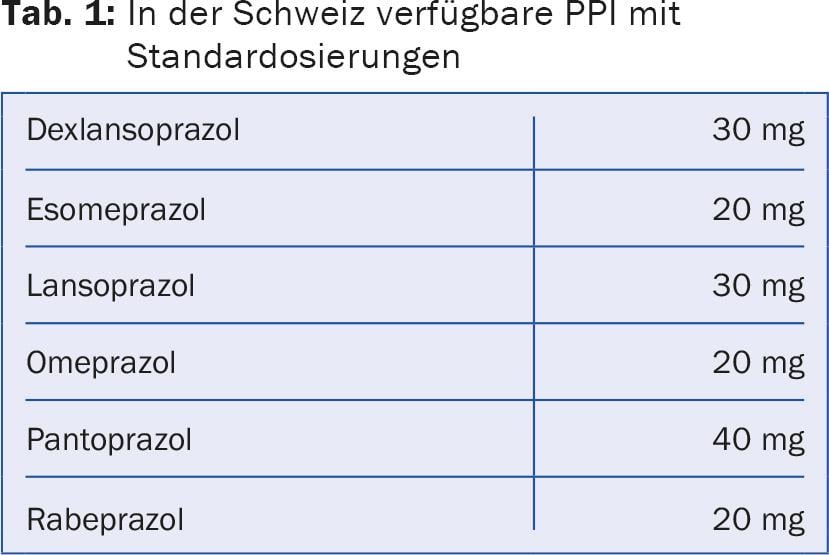

Six different PPI active ingredients are now available in Switzerland (Tab. 1). These differ, among other things, in terms of bioavailability and peak plasma levels. The efficacy of the different agents was compared in some studies, but no clinically relevant differences were demonstrated.

Interactions and safety

PPIs are metabolized by different hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes. The resulting interactions are usually not clinically relevant, but should be examined in any case. Pantoprazole appears to have the lowest interaction potential compared to the other preparations. Specific concerns remain regarding possible interaction of PPI with clopidogrel, but the data in this regard remain controversial [3]. Furthermore, acid suppression may impair the absorption of certain medications.

In short-term use, PPIs are considered very safe. Gastrointestinal side effects such as diarrhea, constipation, flatulence, or nausea are most common. No dose adjustment (at standard dosage) is necessary in renal or hepatic insufficiency. However, there are now concerns about the consequences of long-term administration. Prolonged acid suppression is thought to promote colonization of the gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tracts. Meta-analyses of observational studies partially indicate an increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection or pneumonia [4]. However, no reliable causality can be deduced from these data so far.

In addition, there is evidence of some malabsorption in the setting of long-term PPI therapy. Decreased absorption of magnesium, iron, and vitamin B12 has been described, but clinical relevance is not established [5]. If PPI therapy has been used for many years, regular (for example, annual) level determinations may be considered. However, the data for this is unclear. There are also increasing studies showing a correlation of increased fracture risk with long-term PPI use [6]. An underlying calcium malabsorption is suspected.

PPI for the treatment of peptic ulcers

PPIs heal gastroduodenal ulcers significantly faster than H2 receptor antagonists [7]. A four- to eight-week course of therapy is usually recommended. Healing of gastric ulcers must always be secured endoscopically to avoid missing a gastric carcinoma. If an underlying Helicobacter infection is treated, eradication success should also be assessed. Maintenance therapy after gastroduodenal ulcers with a PPI is usually not indicated. In complicated gastroduodenal ulcers (with bleeding or perforation) in which no correctable or preventable cause can be found (NSAID use, Helicobacter pylori), permanent therapy should be given for secondary prophylaxis. Continuous therapy is also recommended after ulcer bleeding under an anticoagulant substance that cannot be discontinued.

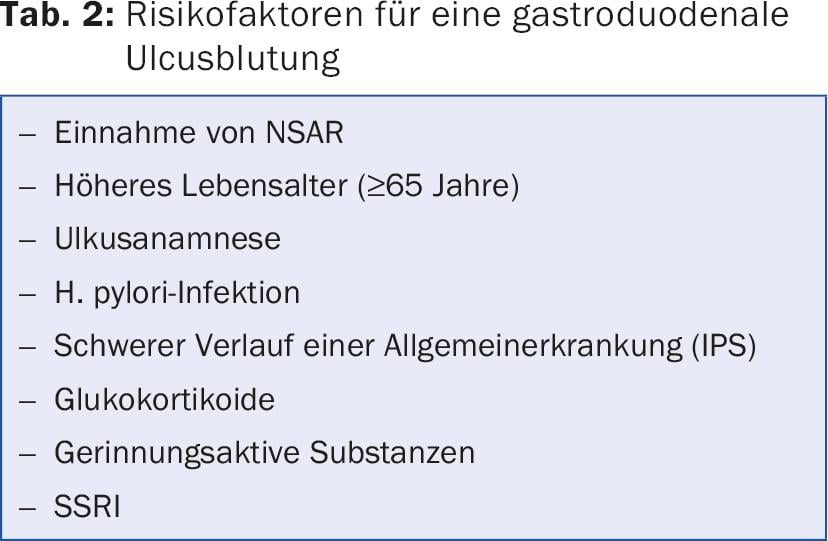

Furthermore, there are certain circumstances that make primary prophylaxis useful. Important risk factors for gastroduodenal ulcer bleeding are listed in Table 2. If therapy with an NSAID is initiated and at least one risk factor is present, concurrent therapy with a PPI is recommended. With alternative use of COX-2 inhibitors, a PPI may not be needed in this situation. PPI prophylaxis should be given when an NSAID is used with an anticoagulant medication or when two or more anticoagulant medications are used concurrently. In critically ill patients undergoing intensive care treatment, a PPI is often administered for prophylaxis of so-called stress ulcers. For this temporary indication, it is best to discontinue the PPI during the course of hospitalization to prevent unnecessary long-term therapy. An often neglected risk factor for gastrointestinal bleeding is the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). A recently published meta-analysis shows a moderately increased risk with SSRI therapy alone, and the risk increases relevantly in combination with NSAIDs [8]. PPI prophylaxis is recommended for this drug combination. In addition, the indication for SSRIs should always be critically questioned, especially after bleeding has occurred.

PPI for eradication of Helicobacter pylori

PPIs are an integral part of any eradication therapy. This usually lasts 7-14 days. If there is uncomplicated Helicobacter-associated gastritis without concomitant ulcer, the PPI does not need to be taken longer than the antibiotic medication. Eradication control should not be performed until four weeks after completion of antibiotic therapy. In addition, for reliable verification of eradication success (avoidance of false negative results), the PPI must be discontinued two weeks beforehand.

PPI for gastroesophageal reflux disease

If gastroesophageal reflux disease is suspected in the absence of typical reflux symptoms, empiric PPI therapy at standard doses can initially be given for four weeks without further diagnostic testing. Thereafter, after successful acute therapy, treatment with a PPI at half the standard dose can be given on demand. Patients who have undergone endoscopy are treated with a standard dose PPI for four weeks for mild reflux esophagitis and eight weeks for severe reflux esophagitis. In mild reflux esophagitis, an outlet attempt is made after acute therapy. If long-term therapy is required, the minimum effective dose should be determined. In severe reflux esophagitis, patients usually require low-dose long-term therapy due to frequent recurrences and risk of complications (bleeding, stenosis) [9].

PPI for functional dyspepsia.

In the absence of alarm symptoms, a time-limited PPI trial can be performed (2-4 weeks). If there is no response, further investigations should be performed.

Correct discontinuation of the PPI

Two placebo-controlled studies in healthy volunteers showed that dyspeptic complaints in the sense of an acid rebound frequently occur after four- and eight-week therapy with a PPI when it is abruptly discontinued [10,11]. The data on this are not conclusive when using PPIs in patients with reflux. The risk of rebound appears to increase with therapy duration.

In principle, PPIs can be stopped without tapering the dosage, regardless of the duration of intake. In the event of an unsuccessful discontinuation attempt (recurrence of symptoms within the first two weeks), the therapy should be restarted and slowly phased out. A clear strategy for this is not recommended, but a tapering over several weeks seems reasonable (reduction to lowest dose, then steady extension of the dose interval). The alternative use of H2 receptor blockers cannot be recommended because they also lead to acid hypersecretion after discontinuation [12]. At best, neutralizing substances can have a supporting effect.

Literature:

- Pasina L, et al: Evidence-based and unlicensed indications for proton pump inhibitors and patients’ preferences for discontinuation: a pilot study in a sample of Italian community pharmacies. J Clin Pharm Ther 2016 Apr; 41(2): 220-223.

- Wolfe MM, et al: Acid suppression: optimizing therapy for gastroduodenal ulcer healing, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and stress-related erosive syndrome. Gastroenterology 2000; 118(2 Suppl 1): S9-31.

- Vaduganathan M, et al: Efficacy and Safety of Proton- Pump Inhibitors in High-Risk Cardiovascular Subsets of the COGENT Trial. Am J Med 2016 Apr 30, pii: S0002-9343(16)30438-7.

- Kwok CS, et al: Risk of Clostridium difficile infection with acid suppressing drugs and antibiotics: meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1011.

- McColl KE: Effect of proton pump inhibitors on vitamins and iron. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104 Suppl 2: S5.

- Yu EW, et al: Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of 11 international studies. Am J Med 2011; 124(6): 519-526.

- Fischbach W, et al: [S2k-guideline Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal ulcer disease]. Z Gastroenterol 2016; 54(04): 327-363.

- Anglin R, et al: Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 811-819.

- DGVS Guideline Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/021-013.html, accessed 07/2016.

- El-Omar E, et al: Marked rebound acid hypersecretion after treatment with ranitidine. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91: 355-359.

- Niklasson A, et al: Dyspeptic symptom development after discontinuation of a proton pump inhibitor: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1531-1537.

- Reimer C, et al: Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology 2009; 137: 80-87.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(9): 8-13