There is clear evidence for oral anticoagulation in mechanical valves. However, individual adjustments of the target INR are sometimes necessary. Moreover, additional platelet inhibition to OAK is becoming routine. The new anticoagulants are not currently approved in valve-operated patients. If there is any doubt regarding proper anticoagulation, consultation with cardiac surgeons or cardiologists should be sought.

In recent years, there have been changes in antithrombotic therapy. New drugs, such as orally administered direct thrombin inhibitors and some potent platelet aggregation inhibitors, as well as the increased use of combined anticoagulation strategies, have made the field complex.

For example, until a few years ago, anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists (VKA) in combination with antiplatelet therapy was the exception. A significantly higher number of bleeding complications were expected with this therapy. In the meantime, such a combined therapy is indicated in many indications.

The recommendations for anticoagulation after heart valve interventions in current guideline publications have become correspondingly more comprehensive and differentiated. On the implanted heart valve side, the variety of prostheses used with different materials and design principles has also increased. After heart valve surgery and the numerically increasing percutaneous interventions on the heart valves (TAVI, MitraClip etc), a differentiated follow-up of the patients must also take place with regard to anticoagulation.

We intend to bring some order to the different anticoagulation regimens with this review, which is strongly based on the latest guidelines of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC 2014) [1,2] and the European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (ESC/EACTS 2012) [3].

How to anticoagulate?

The anticoagulation requirements after heart valve surgery mainly result from the operation performed and the implantation material used: In open cardiac surgery, a distinction is primarily made between reconstruction procedures and valve replacement.

In the reconstruction of a heart valve, there is relatively little contact of foreign material with blood (Fig. 1) and thrombogenicity is thought to be low after three months and endothelialization of the foreign material has occurred.

When the heart valve is replaced, the difference in terms of anticoagulation is given by the use of mechanical (Fig. 2) or biological (Fig. 3) prosthetic valves.

Biological valves are significantly less thrombogenic overall than mechanical valves. In addition, the position of the valve in which the procedure is performed or the position of the valve in which the procedure is performed is decisive for anticoagulation. the prosthesis implantation was performed. Thrombogenicity is lowest in the aortic valve position, which is due to the flow and pressure characteristics present here. Significantly higher risks exist with interventions in mitral valve position due to the lower pressure conditions on the atrial side and corresponding turbulent flow around the foreign material [4,5].

The incidence of bleeding complications with oral anticoagulation (OAK) with VKA is highly dependent on the INR(International Normalized Ratio) target value [6]. Severe bleeding requiring revision under OAK is reported at 1.4-2.6% per year [4,6]. Self-measurement by patients after intensive training can reduce thromboembolic complications and is also cost-effective. However, self-measurement has no significant effect on the rate of bleeding complications [7]. High fluctuations in INR are also associated with reduced survival after valve surgery. If the INR is difficult to adjust, a more stable setting can be achieved by low-dose vitamin K administration.

When OAKs are combined with antiplatelet agents, a minimal increase in severe bleeding complications can be expected with a significant reduction in thromboembolic complications at the current dosage of 100 mg acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) daily [8].

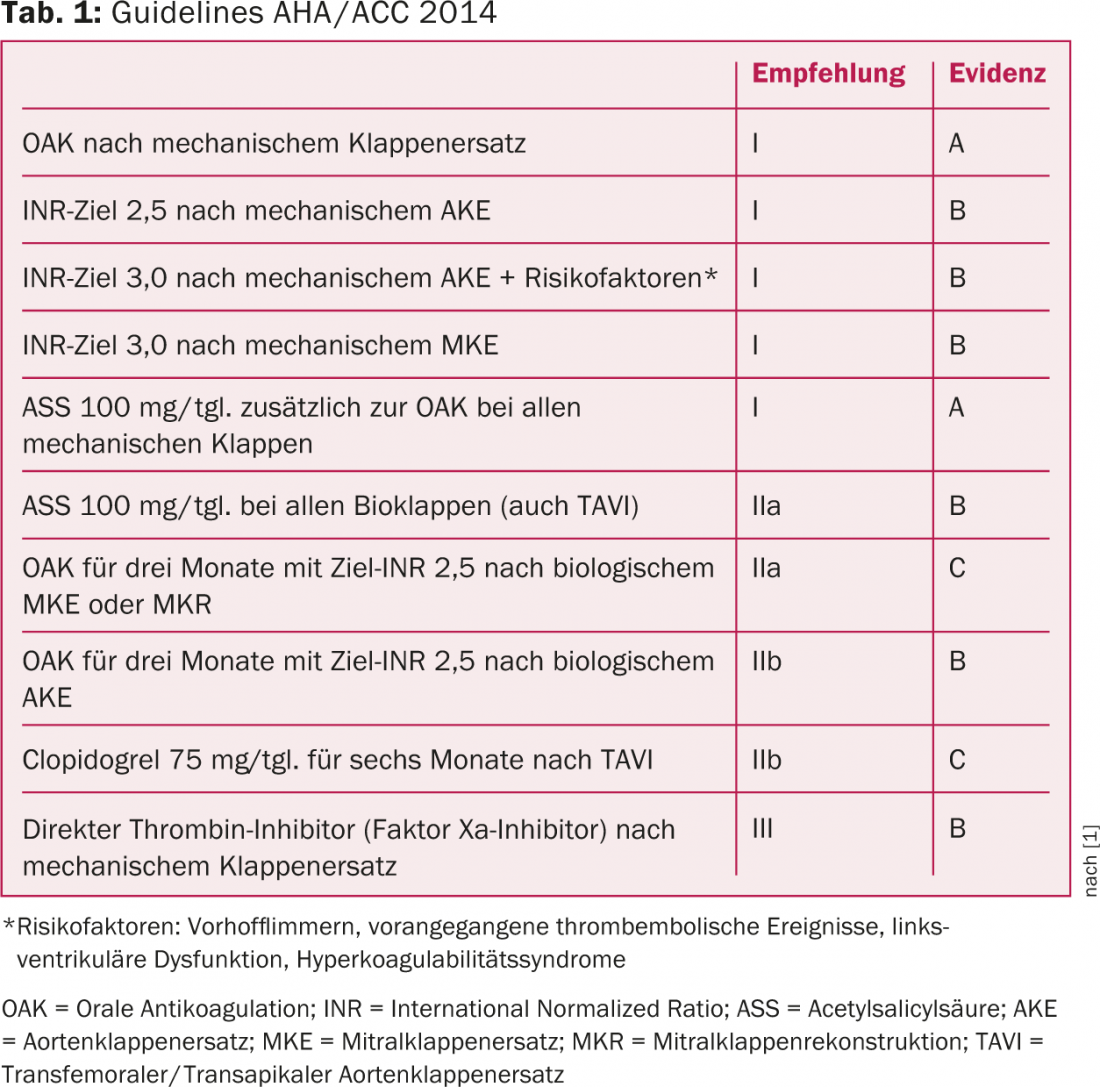

The recommendations for anticoagulation after valve surgery summarized here are based primarily on the latest guidelines of the American professional societies (AHA/ACC 2014) (Table 1) [1–3].

In clinical practice, the INR target values are often still given as a range, e.g., 2.0-3.0. The guidelines recommend that the target value be specified with a margin of variation of 0.5 in each case (e.g., 2.5 +/- 0.5), so that orientation is to the mean value and not to the extreme values.

Aortic valve

After mechanical aortic valve replacement (ACE) with the modern valve types (“bileaflet valves”/”double tilt valves”, Fig. 2), the OAC should be adjusted to an INR of 2.5 and additionally ASA should be administered for life, provided there is no hemorrhagic diathesis. Additional prophylaxis with ASA is new and is a I A recommendation in the latest guidelines (tab. 1) . After biological ACE, it is recommended to administer ASA for life (IIa B recommendation) and to additionally perform OAC with VKA for the first three months postoperatively with a target INR of 2.5 (IIb B recommendation).

At present, these latest recommendations of the 2014 Guidelines are understandably not yet integrated into clinical routine. For example, in our clinic, we have so far dispensed with OAK in the first three months for biological aortic valve prostheses and exclusively recommend ASA for life. For mechanical valves, we prescribe additional antiplatelet therapy with ASA for only three months after valve replacement rather than for life.

Regarding optimal anticoagulation after catheter-based aortic valve implantation (TAVI, Fig. 4) , there are no results from larger prospective or even randomized trials.

The guidelines recommend dual antiplatelet therapy with ASA and clopidogrel (Ilb C recommendation), with clopidogrel stopped after six months. It should be noted, however, that the TAVI population is a patient group that is either at a significantly advanced age or at high surgical risk and, accordingly, often has concomitant indications for OAK with VKA. In this case, a combined anticoagulation is to be carried out in individual consideration, whereby in clinical practice the use of a triple therapy (oral anticoagulation and dual platelet inhibition) is usually dispensed with.

Mitral valve

For mechanical valves in mitral position, OAK with target INR of 3.0 (I B recommendation) and additional ASA for life (I A recommendation) and for biological valves, OAK with target INR of 2.5 for three months and ASA for life is recommended (Tab. 1). Again, there are probably differences in clinical practice between cardiac surgery and cardiology clinics. We currently still recommend ASA for three months in our patients with mechanical mitral valves, and the remaining recommendations are congruent with the AHA. After mitral valve reconstruction, the same recommendations apply as after biological mitral valve replacement.

After MitraClip, our colleagues in cardiology recommend ASA for six months and clopidogrel for an additional three months. If there is a concomitant indication for OAK (e.g., because of atrial fibrillation), this is considered sufficient, even without additional platelet aggregation inhibition. For this still experimental procedure, no long-term studies regarding optimal thrombosis prophylaxis are available so far [9]. MitraClips are not yet listed in the 2014 AHA Guidelines.

Tricuspid valve

The tricuspid valve very rarely requires reconstruction and even more rarely replacement. We treat them according to the same scheme as after mitral valve surgery. Overall, however, the risk of valvular thrombosis is increased in the tricuspid position.

Pulmonary valve

Pulmonary valve surgery is still quite rare except in congenital heart surgery, and evidence-based data on recommendations for anticoagulation are mostly individual considerations, which is why the recommendations of the respective surgeon must be strictly followed, respectively. should be consulted with this. In general, it is believed that the same recommendations apply as for the aortic valve with a target INR of 2.5 for mechanical valve replacement [10].

New drugs for anticoagulation

The hope of many patients, particularly those with mechanical prosthetic valves, lies in the latest oral factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran). These are currently not approved for valve-operated patients in either the United States or Europe. A large multicenter trial (RE-ALIGN) with dabigatran had to be stopped early because of increased bleeding and thromboembolic complications [11], so it will probably be several years before an oral factor Xa inhibitor receives approval for permanent OAK in mechanical valves.

There are no data on the newer antiplatelet agents (prasugrel, ticagrelor) to justify their use in patients undergoing valve surgery.

Summary

In summary, it can be stated that the latest guidelines have not yet been fully adopted in daily practice. Compared with previous recommendations and past practice, there is a clear trend toward stricter OAK with a tendency toward higher target INR. The recommended increase in the INR target value should also be mentioned if, in addition to the indication for OAK because of the valve procedure, there is an additional risk factor for the occurrence of a thromboembolic complication (e.g., atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolic events, left ventricular dysfunction, or diagnosed hypercoagulability syndromes). In addition, the most recent guidelines recommend combined anticoagulation with OAK and ASA much more frequently without time limitation to the first postoperative months.

Literature:

- Nishimura RA, et al: 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129(23): e521-643.

- Nishimura RA, et al: 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129(23): 2440-2492.

- Vahanian A, et al: Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur Heart J 2012; 33 (19): 2451-2496

- Cannegieter SC, et al: Thromboembolic and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Circulation 1994; 89(2): 635-641.

- Roudaut R, et al: Thrombosis of prosthetic heart valves: diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Heart 2007; 93(1): 137-142.

- Cannegieter SC, et al: Optimal oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(1): 11-7.

- Heneghan C, et al: Self-monitoring of oral anticoagulation: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet 2012; 379(9813): 322-334.

- Massel DR, et al: Antiplatelet and anticoagulation for patients with prosthetic heart valves. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; CD003464.

- Alsidawi S, et al: Peri-procedural management of anti-platelets and anticoagulation in patients undergoing MitraClip procedure. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2014; Epub ahead of print.

- Shin HJ, et al: Outcomes of mechanical valves in the pulmonic position in patients with congenital heart disease over a 20-year period. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 95(4): 1367-1371.

- Eikelboom JW, et al: Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(13): 1206-1214.

CARDIOVASC 2014; 13(5): 4-7