Soft tissue sarcomas are rare malignant connective tissue tumors. Therapy is multidisciplinary and should be determined by a sarcoma center. Whoops lesions are unplanned excisions of soft tissue sarcomas without prior diagnosis or treatment. Imaging. Whoops lesions occur in 20-50% of all patients with soft tissue sarcomas. Whoops lesions are associated with an increased rate of local recurrence and poorer prognosis. Tumor tissue remains after unplanned resections. Therefore, extensive resection must be performed, which can lead to great morbidity, increased complications, or even loss of the limb. In Switzerland, all sarcoma disciplines have organized themselves on a national level (www.sarcoma.ch) and published therapy guidelines to avoid misdiagnosis and mismanagement of soft tissue sarcomas.

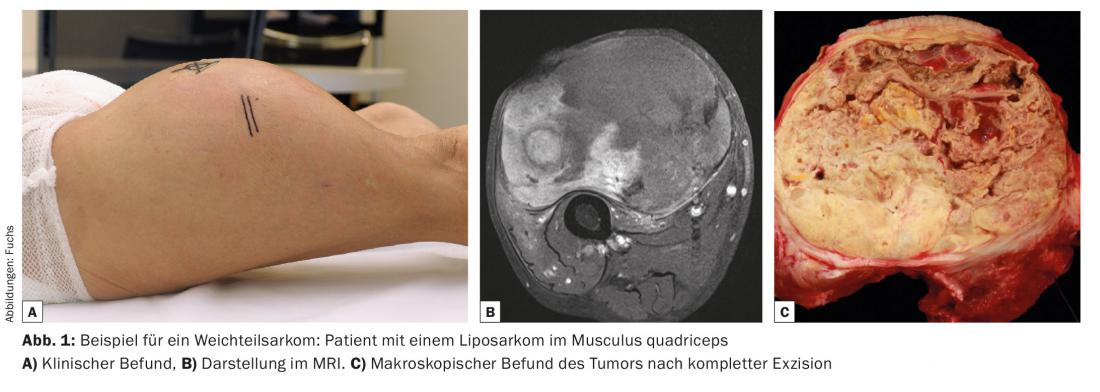

Soft tissue sarcomas represent less than 1% of all adult malignancies. Soft tissue sarcomas can occur in patients of any age and occur with about equal frequency in women and men. Approximately 50% of soft tissue sarcomas are localized to the extremities, with the lower extremity more commonly affected. However, in principle, the occurrence at any localization is possible. Histologically, soft tissue sarcomas form a very heterogeneous group, and the nomenclature is correspondingly complex. With the exception of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors of neuroectodermal origin, they are derived from mesodermal cells and are grouped according to the presumed cell origin: Liposarcomas arise from fat cells (Fig. 1), rhabdomyosarcomas from striated skeletal muscle, and leiomyosarcomas from smooth muscle. However, there are also entities, such as pleomorphic spindle cell sarcoma, in which the cell origin is unknown. Despite the immense diversity, the majority of which is structural, the biological behavior of all soft tissue sarcomas is very similar, and therefore they are often considered a uniform group in diagnosis and management.

Soft tissue sarcoma diagnostics

Most patients with soft tissue sarcoma present to the office with painless soft tissue swelling. There are no clear clinical signs to distinguish a malignant from a benign soft tissue tumor. Suspicious for malignancy are rapid growth of the tumor or a size greater than 5 cm, especially if located subfascially. If the mass is smaller than 5 cm but adherent to the deep fascia or surrounding structures, malignancy is also suspected. Because of the often clinically unclear findings, further diagnosis by imaging and, if necessary, biopsy is crucial in the management of soft tissue sarcomas. If sarcoma is suspected, further imaging is mandatory. MRI is considered the procedure of choice. Additional contrast agent administration (gadolinium) increases the diagnostic accuracy. Advantages of MRI examination compared to ultrasound are better morphologic representation of the tumor and better mapping of the anatomic location with reference to important neurovascular structures.

The Swiss National Sarcoma Advisory Board has established guidelines to guide the treating physician (“minimal work-up requirements”). The guidelines are freely available at www.sarcoma.ch and provide valuable guidance on the situations in which further imaging or biopsy is appropriate.

Biopsy

In principle, all superficial subcutaneous soft tissue tumors larger than 5 cm and all subfascial tumors should be biopsied before surgical resection. It is mandatory that the biopsy be performed by a member of the team that will subsequently perform the surgical resection. Most often, soft tissue sarcomas are biopsied under ultrasound guidance; in some cases, CT-guided biopsy is necessary. Fine-needle aspiration often yields too little tissue to make a clear diagnosis histologically and molecularly. Punch biopsy is therefore considered the gold standard. The biopsy is simple in terms of manual technique, but often intellectually demanding in terms of planning. Since there is a risk of carrying tumor cells into the surrounding tissue with the biopsy, the biopsy tract must also be excised during subsequent surgery. For this reason, the biopsy must be in line with the subsequent surgical skin incision. The biopsy path should never pass close along vessels or nerves or cross anatomic compartments not yet affected. Similarly, the formation of a hematoma must be avoided at all costs to prevent further local spread of the tumor.

Therapy of soft tissue sarcomas

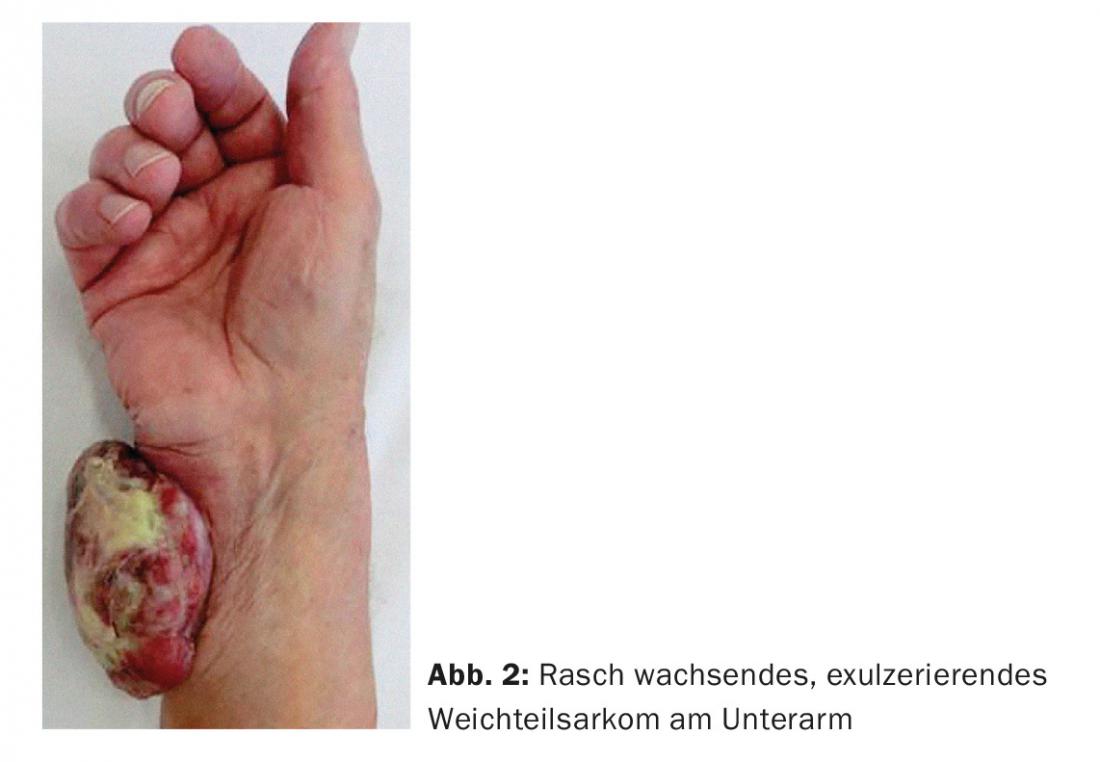

If the diagnosis of soft tissue sarcoma has been confirmed by biopsy after initial suspicion on MRI imaging, a treatment plan is determined at the multidisciplinary sarcoma board. Local treatment is usually by combination therapy, i.e. surgical resection combined with radiation. Whether or not metastases are already present at diagnosis, patients with soft tissue sarcoma require local treatment to avoid local complications. If left untreated, the tumor can become very large, compromising neurovascular structures and ulcerating through the skin (Fig. 2), eventually compromising the limb as a whole.

The goal of surgical resection is to completely remove the sarcoma while preserving tumor-free resection margins and, at the same time, to preserve limb function as much as possible. This is often a balancing act that must be discussed with each patient individually preoperatively.

Radiation therapy is given to all patients to sterilize the surrounding area for better local control than surgery alone. Radiotherapy can be given before or after surgery, although in a randomized controlled trial from Canada, preoperative therapy showed slightly better results [1]. However, the main advantage of preoperative radiotherapy is that the dose and volume of radiation are smaller than in postoperative radiotherapy, which in turn leads to fewer long-term side effects.

Chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas remains not a standard of care but optional in high-risk patients. Meta-analyses show a response rate of about 5-10% with respect to survival and metastases. Thus, the benefit of this therapy is small and often cannot be predicted.

The Whoops lesion

Whoops lesions are defined as tumor resection without prior preoperative diagnosis and without the surgeon having considered the possibility of sarcoma. Frequently, a suspected diagnosis of a benign change (“lipoma”) is made on the basis of a palpation finding. The nodule is then surgically resected, and pathological analysis reveals a malignant finding, to the surgeon’s surprise. Since soft tissue sarcomas are very rare and therefore not thought of as a diagnosis, the literature reports inadequate and inappropriate treatment by surgical practitioners in up to 20-50% of cases.

Clarifications after Whoops lesion

After an unplanned resection of a soft tissue sarcoma, it is imperative that further treatment be pursued at a sarcoma center. The first step is a complete review of all existing findings, reports and images. The available tissue samples should be re-evaluated by a reference pathologist for control to avoid diagnostic errors. The patient is examined clinically with particular attention to the location and course of the surgical scar, presence of hematomas, any drainage sites, and type of wound closure. All these factors can lead to the spread of tumor cells to originally unaffected anatomical compartments and must therefore be taken into account in further treatment.

Next, a complete staging is performed to show local and systemic tumor involvement. Local staging is performed using MRI and contrast to look for remaining tumor tissue in the surgical area and to assess potential contamination from previous unplanned resection. There is often the difficulty that normal postoperative scarring changes cannot always be clearly distinguished from residual tumor tissue. Thus, the sensitivity of MRI after unplanned resection is only 64%. Systemic staging in all cases includes CT thorax and CT of abdomen and pelvis if there is a diagnosis of myxoid liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma.

Treatment of a Whoops lesion

In the vast majority of cases, a resection of the surgical area is performed. The goal here is to remove the remaining sarcoma and potentially contaminated tissue with adequate resection margins. The rationale for resection is based on the observation that residual tumor tissue is almost always found after an unplanned resection, at least microscopically (24-60%). This fact may influence the further prognosis of the patient. Post-resection is often difficult; reasons include scar tissue, altered anatomic layers, and lack of a mass to use as a guide. Inconveniently located scars and exit sites from previous drains further complicate the situation.

In addition to surgical post-excision, radiation therapy may be performed. In contrast to planned primary resections of soft tissue sarcomas, where radiation is an integral part of therapy, the role of radiotherapy in the treatment of Whoops lesions remains less clear and must be discussed individually in the sarcoma board. Radiation alone is used only when postresection would be too mutilating for the patient. Current data show a slightly better prognosis when surgery is combined with radiation [2].

Chemotherapy is controversial in the treatment of Whoops lesions. The available data are sparse and often of insufficient quality. However, if metastases are already present at initial staging prior to resection, chemotherapy must certainly at least be discussed with the patient.

Consequences of a Whoops lesion

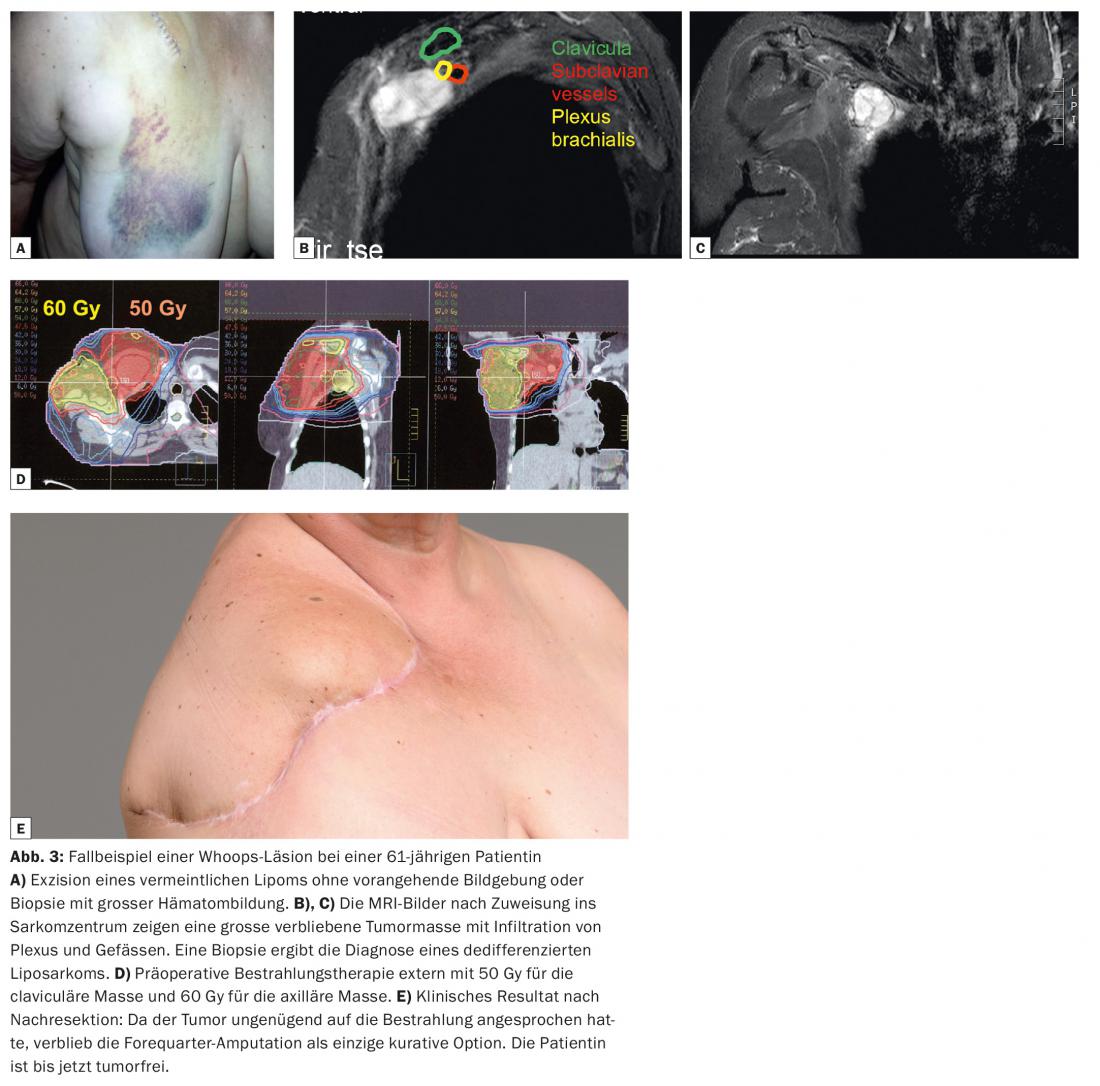

Unplanned, incorrect excisions of soft tissue sarcoma have far-reaching consequences for the affected patient. Overall, the 5-year survival rate is lower and the local recurrence rate is higher than in patients with adequate interdisciplinary therapy [3–5]. Local recurrence rates after Whoops lesions of up to 39% have been reported in the literature. In addition, disease-specific survival at five years (69.8%) is significantly lower than with planned resection (87.5%). Post-resection of the former surgical site may result in large skin and soft tissue defects. Thus, a soft tissue flap or skin graft must be used much more frequently (in up to 30% of cases) to achieve sufficient soft tissue coverage. This leads to a higher perioperative complication rate and poorer functional outcomes. As shown in our case study (Fig. 3), in some cases even amputation must be considered, which would have been primarily avoidable.

Summary

Unplanned excisions of soft tissue sarcomas may occur in 20-50% of patients with newly diagnosed soft tissue sarcoma. These should therefore already be referred primarily to a sarcoma center. Resection of the tumor bed is usually recommended after an unplanned resection, often in combination with radiation therapy to remove as much of the often remaining tumor tissue as possible. Post-excision surgery is more extensive than primary surgery, results in greater morbidity, and more often requires extensive soft tissue reconstruction. After a Whoops lesion, radiation alone appears to be insufficiently effective, but it is used as adjuvant therapy to surgery if surgery to mutilate must be considered. Unplanned excisions of soft tissue sarcomas are associated with a higher rate of local recurrence and a generally worse prognosis. The Swiss National Sarcoma Advisory Board (www.sarcoma.ch) has therefore established guidelines to prevent diagnostic errors and mismanagement.

Literature:

- O’Sullivan B, et al: Preoperative versus postoperative radiotherapy in soft-tissue sarcoma of the limbs: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 359(9325): 2235-2241.

- Jones DA, et al: Management of unplanned excision for soft-tissue sarcoma with preoperative radiotherapy followed by definitive resection. Am J Clin Oncol 2014.

- Chandrasekar CR, et al: The effect of an unplanned excision of a soft-tissue sarcoma on prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008; 90(2): 203-208.

- Noria S, et al: Residual disease following unplanned excision of soft-tissue sarcoma of an extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78(5): 650-655.

- Potter BK, et al: Local recurrence of disease after unplanned excisions of high-grade soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466(12): 3093-3100.

Further reading, Key paper:

- Pretell-Mazzini J, et al: Unplanned excision of soft-tissue sarcomas: current concepts for management and prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015; 97(7): 597-603.

Further literature list from the publisher

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(8): 26-29.