In a study involving patients at the University Hospitals of Zurich and Basel, researchers are comprehensively and extremely precisely investigating the molecular and functional characteristics of tumors. This should enable physicians to better determine which treatment is particularly well suited to a patient’s cancer and therefore effective.

Researchers from the University Hospitals of Zurich and Basel as well as ETH Zurich, the University of Zurich and the pharmaceutical company Roche set themselves the goal of improving the diagnosis of cancer using a variety of state-of-the-art molecular biological methods. In the “Tumor Profiler” project, they determine the molecular profile of the tumor in cancer patients, on which the effectiveness of many new cancer drugs depends. This profile makes it possible to provide treating physicians with personalized and improved therapy recommendations. Three years ago, the researchers started a large-scale clinical trial in 240 patients with metastatic melanoma, metastatic ovarian cancer or acute myeloid leukemia. The scientists are comprehensively studying the tumors of these study participants. This gives them a comprehensive insight into the cellular composition and biology of each tumor.

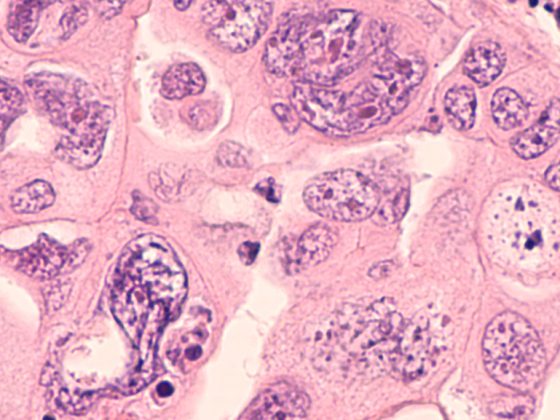

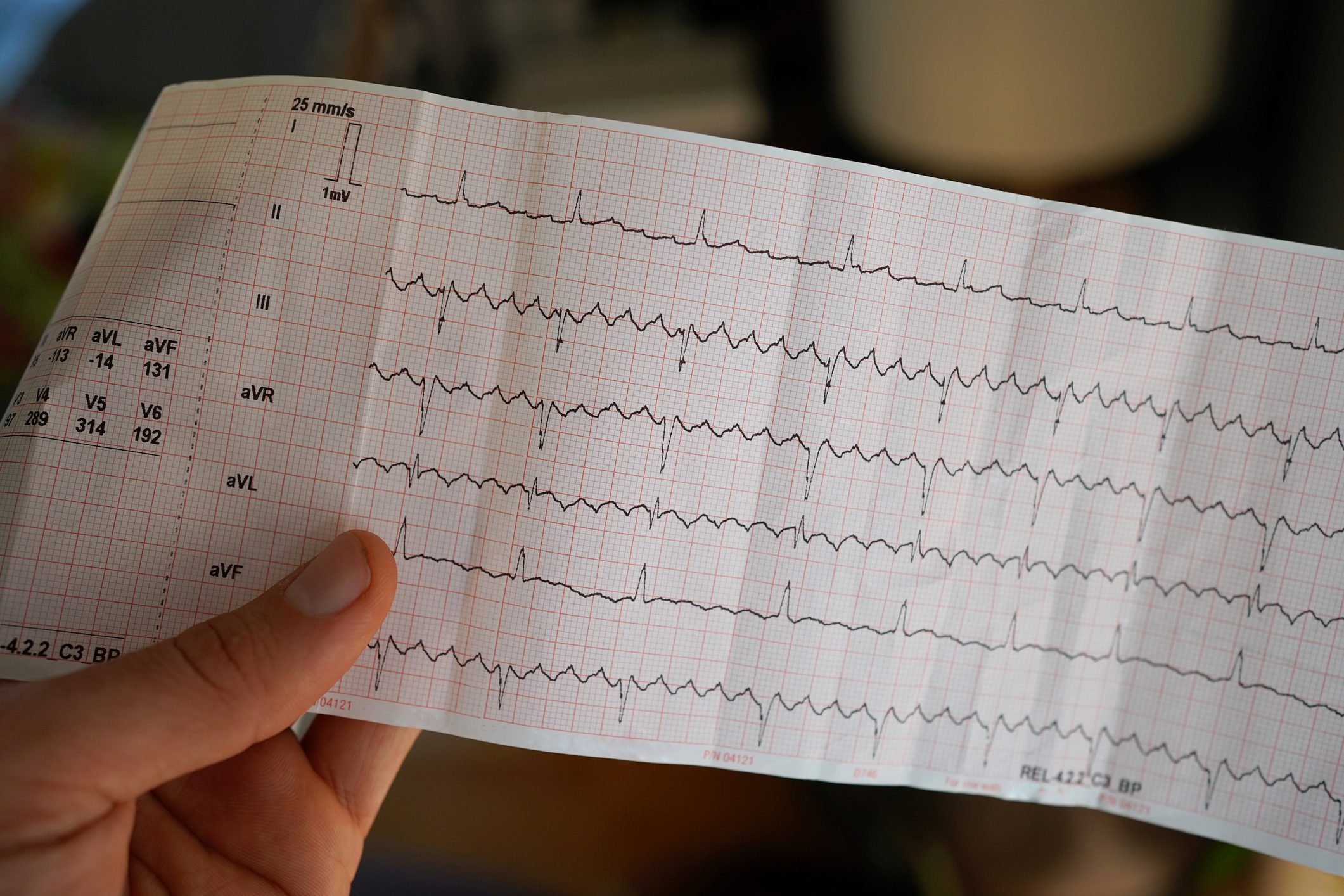

What is new about the Tumor Profiler study is that it examines tumors using a variety of complementary methods in order to gain new insights from their combination. The study thus goes much further than the limited use of molecular biology methods as used in leading hospitals. “We have brought together all the cutting-edge technologies in this field from ETH Zurich and the project partners involved. Together with physicians from Zurich and Basel, we have developed something that advances cancer medicine and serves patients,” says Mitchell Levesque, professor at the University Hospital Zurich and one of the corresponding authors of the technical publication. The studies include those on the DNA, RNA and proteins of the cancer cells. By studying at the single-cell level, the researchers also capture the cellular diversity in a tumor, which includes not only tumor cells but also cells of the immune system. “We examine the whole tumor and its immediate surroundings,” says Andreas Wicki, chief physician at University Hospital Zurich. Part of the analysis also includes functional tests, in which biopsies of the tumor are treated with drugs in the laboratory to determine which drugs work. Information from medical imaging as well as other patient data is also taken into account.

Influence on treatment decisions. “This means that huge amounts of data accumulate per patient, which we process and analyze using data science methods,” says Gunnar Rätsch, professor at ETH Zurich and one of the corresponding authors of the technical publication. The tumor profiler findings are then made available to physicians, who discuss them at interdisciplinary tumor board meetings. Because detailed molecular studies are referred to in science by terms ending in -omics (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics), the approach that encompasses very many “omics domains” is called a multi-omics approach. “With the Tumor Profiler study, we want to show that the broad use of molecular biology methods in cancer medicine is not only feasible, but also has a concrete clinical benefit,” says Viola Heinzelmann, Chief of Gynecological Oncology at the University Hospital Basel. Thus, the researchers in the study are also investigating whether and what influence the molecular analyses had on the physicians’ treatment decisions.

In the long term, the tumor profiler approach is about expanding therapy options for patients in terms of personalized medicine. This includes, for example, the question of whether patients would benefit in certain cases if they were not treated with drugs of standard therapy, but with drugs approved for other types of cancer. Data collection for the Tumor Profiler study will be completed in two months. Subsequently, the scientists involved will evaluate the data. (This study was funded in part by Roche and in part by the participating universities and university hospitals).

Source: Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich)