Drug interactions can end dangerously. Family physicians in particular have a lot to do with multimorbid elderly patients. Interactions of the most common drugs should therefore be known.

A 62-year-old man with a major depressive episode, adjusted with 40 mg/d citalopram and 300 mg/d bupropion, presents to the primary care physician’s office with acute back pain. Since acetaminophen has no effect, 50 mg of tramadol is prescribed on an eight-hourly basis, resulting in the man presenting to the emergency department three days later with extraneous history of anxiety, confusion, and profuse sweating. Clinical examination reveals a blood pressure of 160/90 mmHg, a pulse of 110/min, a respiratory rate of 18/min, and a body temperature of 37.5°C.

Interpretation: “If serotonergic toxicity or a serotonin syndrome is suspected, extrapyramidal motor signs should be examined in addition to signs of autonomic and cognitive dysfunction,” says PD Dr. med. Michael Bodmer, Head of Internal Medicine, Cantonal Hospital Zug. Indeed, the patient showed increased reflexes and inducible clonus.

A 46-year-old with major depression treated with 100 mg/d sertraline per day gets over-the-counter dextromethorphan (Nyquil®: 30 mg/30 ml and doxylamine/paracetamol) at the pharmacy and drinks 240 ml during one night. The following day, he presents to the emergency department with BP 155/89 mmHg, pulse 110/min, and temperature 39°C, as well as dilated pupils, hyperreflexia, tremor, and increased muscle tone in the lower extremities.

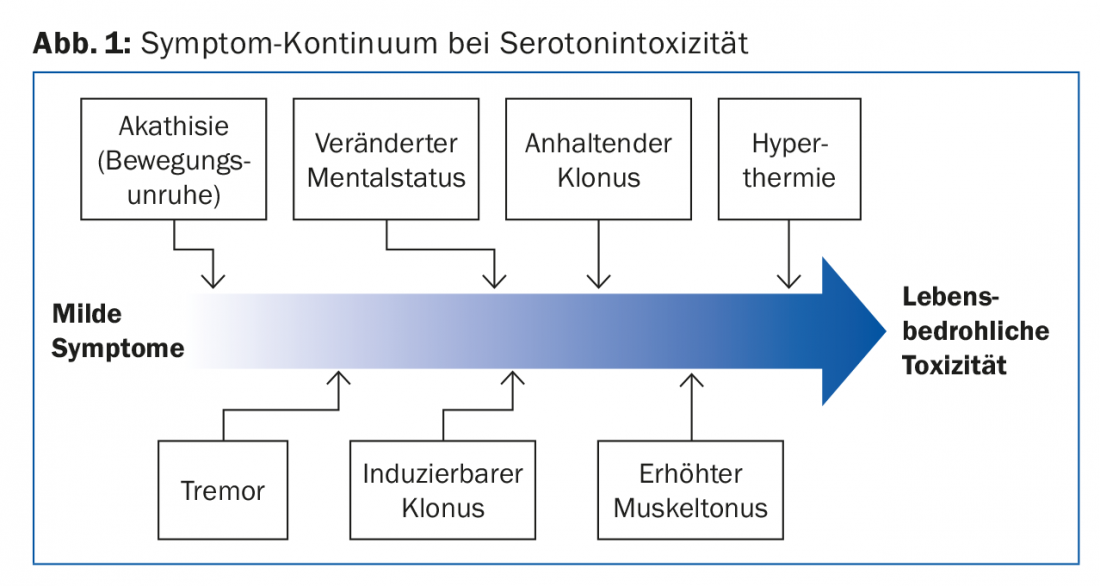

Interpretation: “At the latest with hyperthermia, acute serotonin toxicity, which is due to an oversupply of serotonin in the synaptic cleft, becomes dangerous or life-threatening. The effect is found rapidly and is dose-dependent. Mild, non-specific symptoms may occur at the beginning,” the speaker explained. Initially, one often encounters gastrointestinal signs (bloating, stool irregularities, possibly diarrhea). The continuum from mild to life-threatening symptoms is shown in Figure 1 . The phenomenon usually only becomes relevant when two substances are taken. Among the best known and most common in everyday life:

- Antidepressants: (selective) serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, hypericum extracts (SRI), moclobemide.

- Opioid analgesics: especially tramadol (SRI and serotonin-releaser)

- Miscellaneous: For example, linezolid (MAO A inhibitor), dextromethorphan, chlorphenamine.

Hyperkalemia

An 82-year-old man with NYHA IV heart failure is hospitalized (BP 110/90 mmHg, pulse 100/min, saturation 90% below RL, discontinuous collateral pulmonary murmurs bilaterally, jugular veins congested). His medication history includes spironolactone 25 mg (1-0-0), ramipril 5 mg (1-0-1), aspirin cardio 100 mg (1-0-0), metoprolol 100 mg (1-0-1), and torasemide 10 mg (2-0-0).

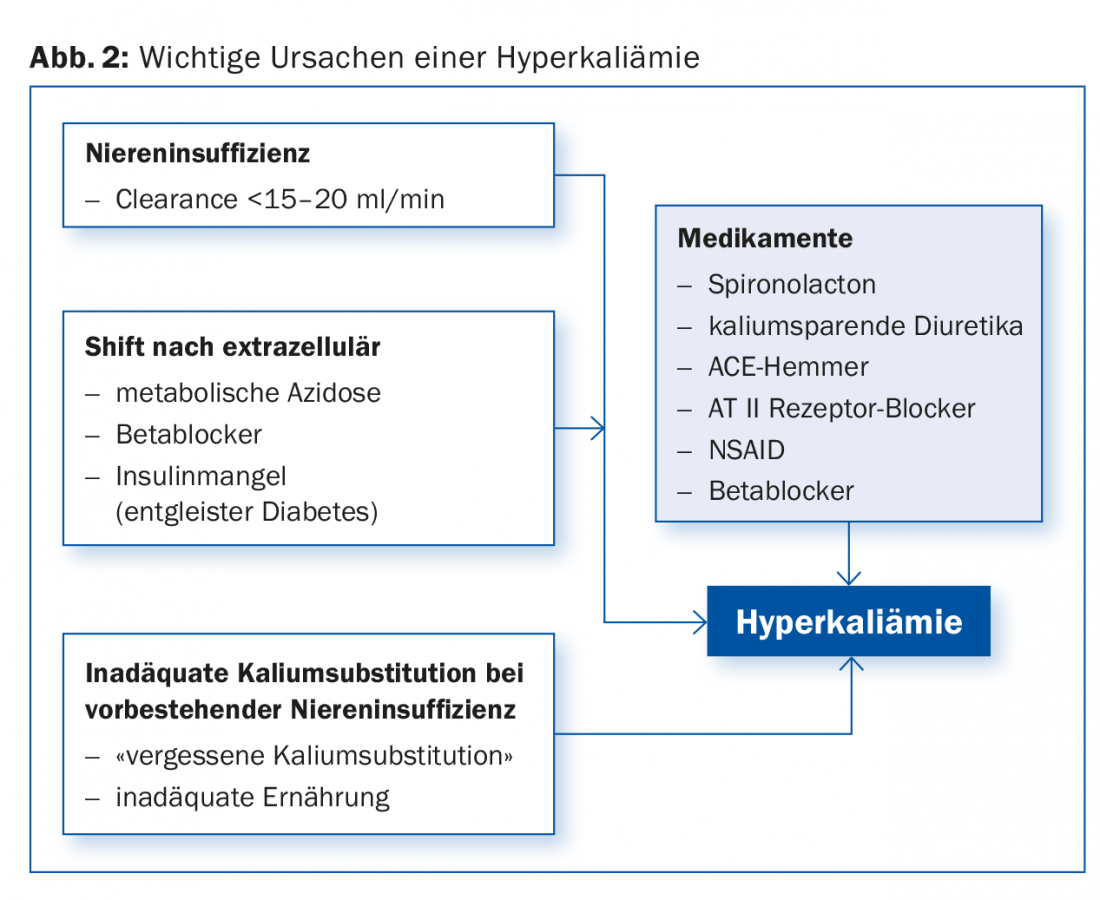

Interpretation: “The working hypothesis of hyperkalemia was consistent with the ECG findings. In the laboratory, we found a severe form with 8.2 mmol/l (normal would be 3.6-4.5 mmol/l) as well as severe renal insufficiency with a calculated creatinine clearance (eGFR) according to Cockcroft-Gault of 29 ml/min,” says Dr. Bodmer. Figure 2 provides an overview of the most important causes of hyperkalemia.

Since the RALES trial, which demonstrated a survival benefit of spironolactone in severe symptomatic HI with impaired ejection fraction, spironolactone prescriptions have steadily increased. ACE inhibitors are additionally indicated in this patient group. However, combination with ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II antagonists, and potassium-sparing diuretics, indomethacin, trimethoprim, and other hyperkalemia-causing drugs may result in life-threatening hyperkalemia. There is epidemiologic evidence that hospitalizations and death rates due to hyperkalemia have also increased since RALES [1]. Another case illustrates the problem.

A 64-year-old type 2 diabetic with systolic heart failure presents for generalized weakness. Previously, he took trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for seven days due to pyelonephritis. History reveals status post myocardial infarction and arterial hypertension. In terms of medication, he receives lisinopril, metoprolol, furosemide and insulin. The laboratory shows marked hyperkalemia.

Interpretation: The following risk factors could play a role in the patient: First, heart failure predisposes to reduced arterial blood volume (less urinary flow distal-tubular, less potassium secretion). Second, diabetes is often associated with hypoaldosteronism or aldosterone resistance. Metabolic acidosis, in turn, predisposes to hyperkalemia, and lisinopril directly leads to decreased aldosterone release. Finally, trimethoprim is a potassium-sparing diuretic with comparable efficacy to amiloride. The addition of the latter drug was probably crucial for the hyperkalemia in this case [2].

NOAC

A 53-year-old epileptic (taking 600 mg carbamazepine every twelve hours) is given thrombosis prophylaxis postoperatively after implantation of a knee prosthesis, first with enoxaparin, then in the course change to rivaroxaban 10 mg/d (because the patient does not want injections). After discharge, he suffers from acute respiratory distress within days. Pulmonary embolism is found.

A 45-year-old epileptic presents to the emergency department with a swollen lower leg. Circumferential difference is 3.5 cm, livid coloration and calf tenderness are found. Finally, deep vein thrombosis is diagnosed and rivaroxaban 20 mg/d is started. In the course after six days phlegmasia coerulea dolens on the right leg.

Interpretation: “First, in the latter case, it is striking that the starting dose of rivaroxaban was incorrectly chosen. Second, carbamazepine is a potent inducer of CYP 3A4 and P-glycoprotein. It can therefore reduce the plasma concentrations of concomitantly administered substances that are metabolized mainly via CYP 3A4,” the speaker said.

Rivaroxaban is metabolized a good %–65% times by CYP 3A4 as well as CYP 2J2. Concomitant administration of rivaroxaban and strong CYP 3A4 inducers such as rifampicin, phenytoin, phenobarbital, St. John’s wort, or even carbamazepine may thus result in decreased plasma concentrations of rivaroxaban. “A medication history is therefore mandatory with NOAC administration,” Dr. Bodmer noted. “Especially with rivaroxaban and apixaban, comedication with strong CYP 3A4 and/or P-glycoprotein inducers, but also inhibitors, should be avoided. The latter include, for example, ketoconazole or ritonavir. They may increase the plasma concentration of NOAC to a clinically relevant extent.”

With edoxaban, comedication with potent P-glycoprotein inhibitors should be avoided. In pharmacokinetics studies, concomitant administration of edoxaban and the P-gp inhibitors ciclosporin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, quinidine, or verapamil resulted in increased edoxaban plasma concentrations.

Antibiotics absorption

A 62-year-old woman on metformin, lisinopril/HCT, ibandronate, and Calcimagon D-3 is prescribed ciprofloxacin (2×500 mg/d p.o. for one week) for uncomplicated pyelonephritis. In addition, she takes Riopan® Gel. Where is the danger here?

Interpretation: “Both calcium and antacid use can be problematic when combined with an antibiotic,” the expert explained. “Whereby calcium preparations still perform somewhat better.” The potential loss of effect of the antibiotic here is based on polyvalent cations (chelate) and reduced solubility/precipitation with antacids [3,4]. Ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin are most affected by the interaction. Therefore, these very antibiotics should be added two hours before taking polyvalent cations.

Take-Home Messages

In St. Gallen, PD Dr. med. Michael Bodmer gave an overview of the dangers and pitfalls of drug interactions. He used case histories to guide the visitors of the Eastern Switzerland Emergency Symposium through this complex topic. This involved medications that are also commonly prescribed in practice. The focus was on multimorbid elderly patients with complex medication regimens. The family doctor, as the first point of contact, plays a crucial role here.

Source: East Switzerland Emergency Symposium, March 16, 2017, St. Gallen

Literature:

- Juurlink DN, et al: Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med 2004 Aug 5; 351(6): 543-551.

- Palmer BF, Clegg DJ: Hyperkalemia. JAMA 2015 Dec 8; 314(22): 2405-2406.

- Sahai J, et al: The influence of chronic administration of calcium carbonate on the bioavailability of oral ciprofloxacin. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1993 Mar; 35(3): 302-304.

- Nix DE, et al: Effects of aluminum and magnesium antacids and ranitidine on the absorption of ciprofloxacin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1989 Dec; 46(6):700-705.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(4): 52-54