DOAK are at least equal to standard therapy with VKA in non-valvular VCF and venous thromboembolism in terms of safety and efficacy. The intracranial bleeding risk is halved. Consequently, they represent a valid alternative to VKA. In case of renal insufficiency, the limits of use must be closely observed. With a short half-life of DOAK and thus a high demand for medication adherence, compliance and good instruction play an important role. Further studies that directly compare DOAKs with each other and test additional indications are important to enable individualized treatment.

For more than 50 years, vitamin K antagonists (VKA) were the only peroral form of anticoagulation. Despite excellent efficacy and a high degree of familiarity, their use is subject to various limitations such as interactions with drugs and diet, close monitoring of therapy and dose adjustments. These, in turn, together with respect for severe bleeding, have a critical impact on patient and physician acceptance and may ultimately be partly responsible for the underrepresentation of VKA in AF (approximately 50%) [1, 2].

In recent years, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) with rapid onset of action without the need for parenteral bridging and favorable pharmacokinetics with a predictive dose-response relationship and no need for close therapeutic monitoring have entered the market. With good efficacy and safety of these preparations, there are points to be aware of, such as dependence on renal function, drug interactions, and specific antidotes not yet available in clinical practice. In the following, an overview of the clinical aspects of oral anticoagulation from an internal medicine perspective will be developed. The goal is to facilitate the growing therapy selection options in the sense of individualized medicine.

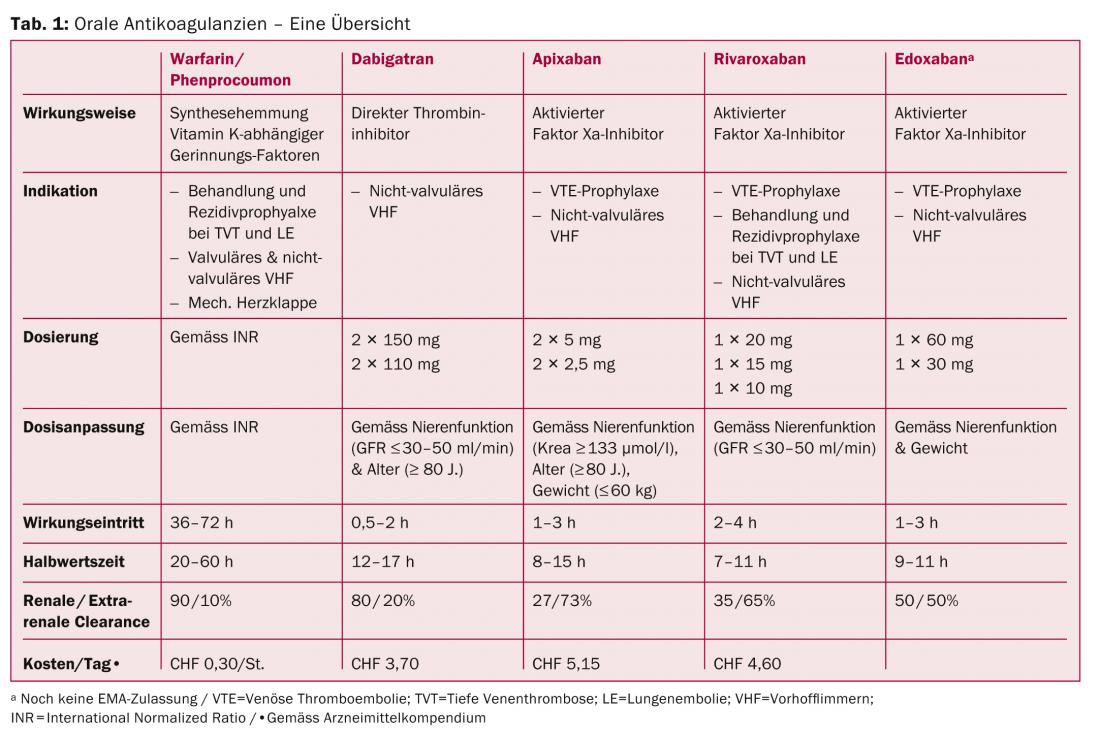

New DOAK – An Overview (Tab. 1)

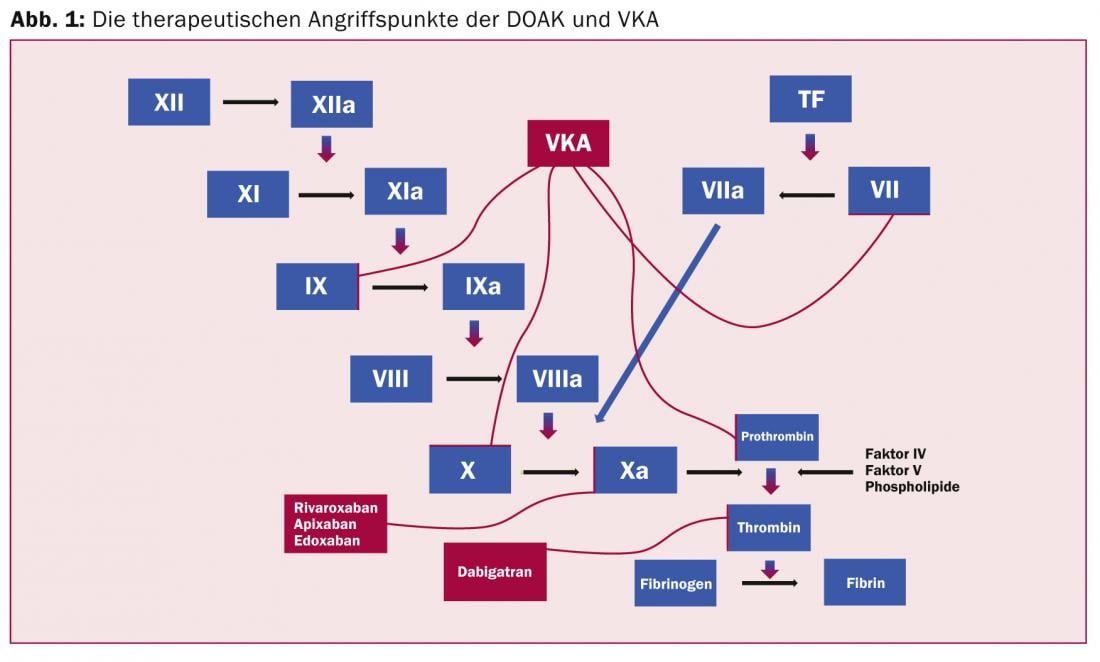

Direct factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban; apixaban; edoxaban): The anticoagulant effect unfolds via direct inhibition of factor Xa (Fig. 1) and secondarily via indirect inhibition of thrombin generation.

One factor Xa molecule can generate over 1000 thrombin molecules in the prothrombinase complex.

Direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran): The enzyme thrombin converts fibrinogen to fibrin and amplifies its own formation by activating factors V, VIII and XI. In addition, it activates the fibrinogen-stabilizing factor XIII, as well as the platelets in a receptor-dependent manner. Indirect thrombin inhibition via antithrombin has been known with unfractionated heparin for years. The indirect mechanism, however, only inhibits free, but not fibrin-bound thrombin, which, however, also plays an important role in thrombus growth. The direct thrombin inhibitors are able to inhibit both free and bound thrombin [3].

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) and DOAK

Until now, the standard treatment for venous thromboembolism (VTE) has been parenteral blood thinning with a heparin preparation for at least five days followed by treatment with VKA. In addition to the need for regular monitoring, this also entailed an increased risk of bleeding in the context of overlapping anticoagulation.

The RECORD and EINSTEIN studies demonstrated an effect for rivaroxaban in thromboprophylaxis after orthopedic surgery (hip and knee TP) and in the treatment and secondary prophylaxis of pulmonary embolism including VTE equivalent to standard therapy (VTE recurrence 2.1% for rivaroxaban and 3% for VKA) with a statistically significant lower bleeding rate (1.1% vs. 2.2%; HR 0.49, CI 0.31 – 0.79; p=0.003) [4, 5]. The direct peroral route of administration is an important advantage.

Apixaban as postoperative thromboprophylaxis after orthopedic surgery and as treatment and secondary prophylaxis of venous thromboembolic events was investigated in the ADVANCE and AMPLIFY trials, respectively. Outcome was equal to standard therapy in terms of primary endpoints (VTE, death) with smaller bleeding rate (0.6% vs. 1.8%, HR 0.31; 95% CI 0.17- 0.55) [6, 7].

In the RE-COVER trials, dabigatran had an equivalent preventive effect on recurrent VTE (HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.45-1.48) after initial parenteral anticoagulation of approximately nine days duration compared with a VKA, with comparable major bleeding rates (1.6% for dabigatran vs. 1.9% for VKA, HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.45-1.48) and lower overall bleeding rate (16.1% vs. 21.9%, HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.59-0.85).

Intracranial hemorrhage rates were lower with all preparations compared with VKA.

All three DOAKs have had successful extension studies, apixaban also at a reduced dose of 2×2.5 mg and dabigatran also compared with VKA.

Currently approved in Switzerland for the treatment and secondary prophylaxis of VTE is rivaroxaban at a dose of 2×15 mg over three weeks followed by 1× 20 mg. Apixaban and rivaroxaban are both approved for postoperative thromboprophylaxis after hip and knee TP at doses of 2×2.5 mg and 1×10 mg, respectively.

Atrial fibrillation and DOAK

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia with great clinical and health economic relevance.

In addition to VKA, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban are now approved for prophylaxis of thromboembolic events in non-valvular VCF.

The ROCKET-AF trial demonstrated non-inferior prevention of stroke and systemic embolic events for rivaroxaban compared with VKA treatment in over 14 000 patients (event rate 2.12% vs. 2.42%, HR 0.88) with even significant superiority in the on-treatment analysis. Besides, significantly decreased intracerebral hemorrhage rate (HR 0.67, CI 0.47-0.94, p=0.019) and also significantly less fatal hemorrhage (HR 0.50, CI 0.31-0.79, p=0.003) were shown with increase in gastrointestinal bleeding risk (HR 1.25, CI 1.01-1.55, p=0.04) [8].

In the ARISTOTLE trial, apixaban was compared to VKA in over 18 000 patients with similar efficacy against ischemic stroke (0.97% vs. 1.05%, HR 0.92, CI 0.74 -1.13, p=0.42) with significant reduction in hemorrhagic stroke (HR 0.51, CI 0.35-0.75, p<0.001) and mortality (HR 0.89, CI 0.80 – 0.99, p=0.047) [9].

For dabigatran at the higher dose, the RE-LY trial demonstrated a significantly reduced ischemic stroke rate (RR 0.76, CI 0.60-0.98, p=0.03, ARR 0.28%/patient-year) compared to VKA therapy with reduction in intracranial hemorrhage risk. In addition, there was a slight increase in the rate of coronary events (0.82% vs. 0.64%, p=0.09), which became significant in the meta-analysis, with no effect on all-cause mortality [10, 11].

A meta-analysis of phase III trials of the four DOAKs demonstrated a favorable benefit-risk profile for the entire group, with a significant reduction in mortality of approximately 10% and intracranial hemorrhage rate of approximately 50%, with the same efficacy against ischemic events and, however, increased gastrointestinal bleeding rate.

Similarly, for clinically relevant risk groups for ischemic and hemorrhagic events (age >75 years, history of CVI, renal insufficiency), consistency of efficacy and safety of DOAK treatment was demonstrated

[12].

Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions

Although DOAKs are characterized by fewer interactions than VKAs, there are some pharmacokinetics considerations for the prescribing clinician to keep in mind.

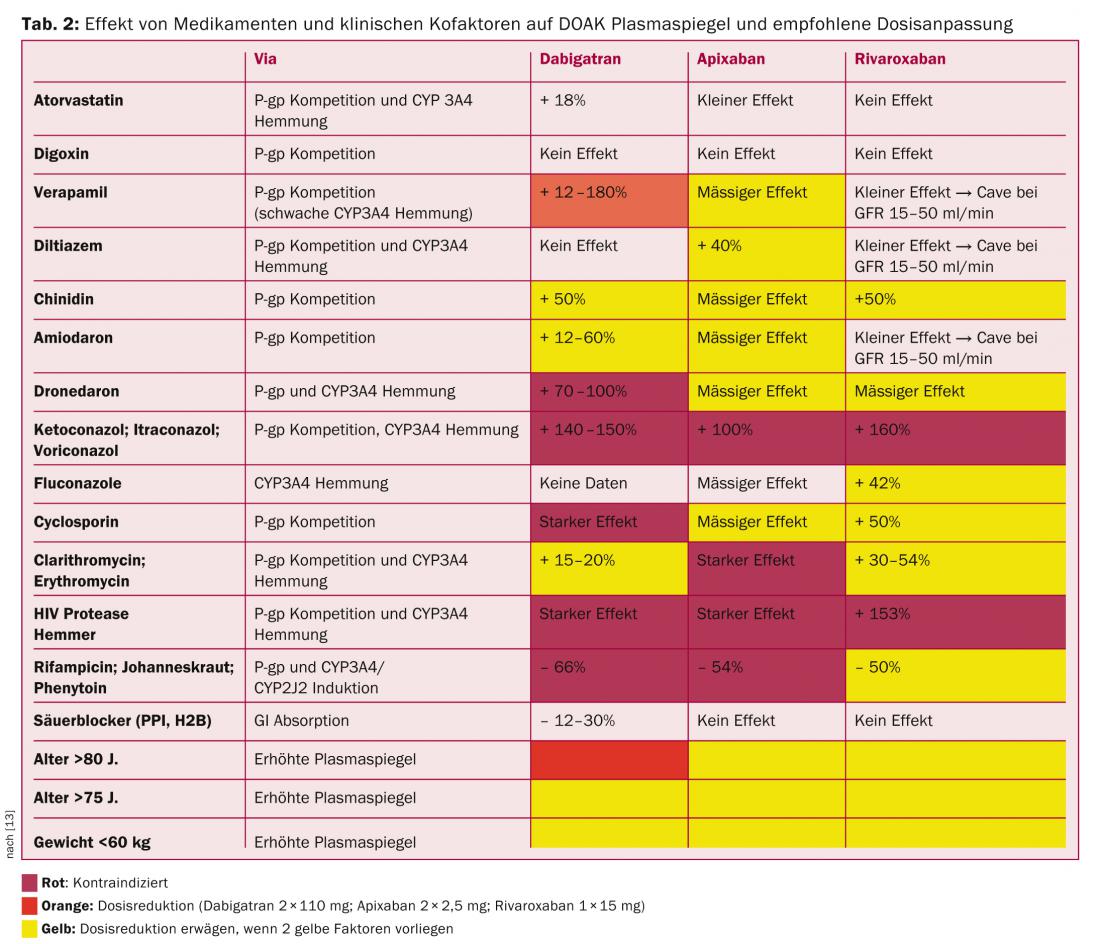

Thus, significant intestinal re-secretion via the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) transporter is significant with all DOAKs except rivaroxaban. Competitive inhibition of this pathway causes increased plasma levels. Many drugs, often used in patients with VHF, are P-gp substrates and should be used with caution or not at all, especially with dabigatran (verapamil, dronedarone, amiodarone, quinidine).

The CYP3A4 enzyme system is significantly involved in the hepatic elimination of rivaroxaban and apixaban. In this sense, combinations with potent inhibitors of this pathway (clarithromycin, erythromycin, ritonavir, ketoconazole, fluconazole) and inducers (rifampicin, St. John’s wort, carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital) must be avoided if possible (Table 2) [13].

The DOAKs themselves do not affect the aforementioned enzyme systems and can be combined with other substrates (midazolam, atorvastatin, digoxin).

Combinations of all DOAKs with antiplatelet agents and NSAIDs increase the risk of bleeding by at least 60% [14, 15] and should be treated with caution, with up to 30% of patients on additional antiplatelet therapy in the large trials.

With 30-40 percent increase in bioavailability of rivaroxaban with accompanying food intake, it should be taken with meals.

Therapy control under DOAK

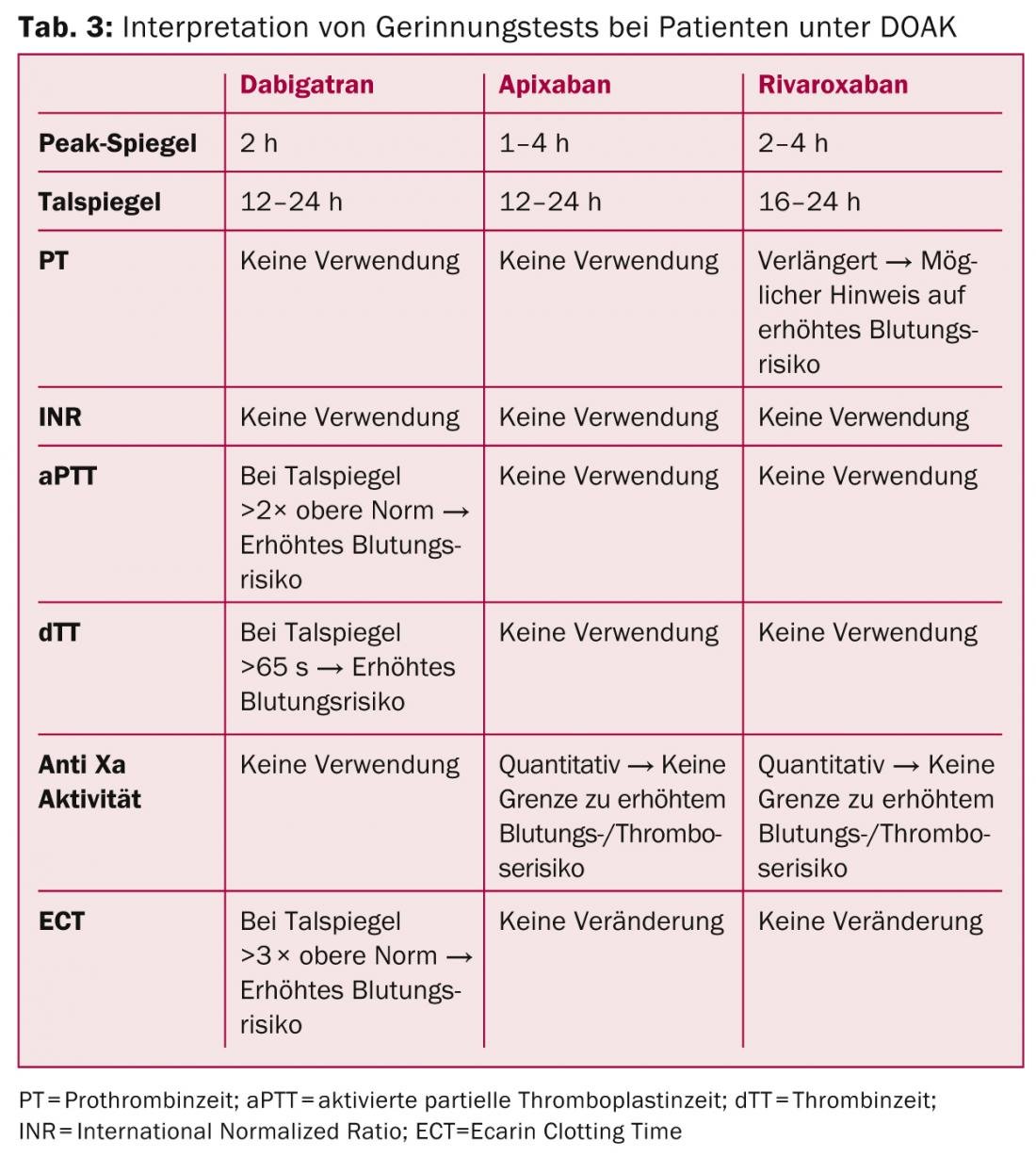

An important advantage of DOAK is that regular therapy checks are no longer necessary. In certain cases, however, statements about the anticoagulant effect of a treatment would be of clinical relevance. For example, severe bleeding, thromboembolic event, urgent surgical intervention, possible overdose, or problematic compliance.

In the case of thrombin inhibitors, the “Ecarin Clotting Time” (ECT) provides a direct indication of their activity, albeit with limited availability. Prolongation of aPTT to double at 12 hours (valley level) may indicate an increased risk of bleeding with dabigatran. A standardized thrombin time measurement (e.g., Hemoclot® for dabigatran) can more accurately reflect clotting status, with a direct thrombin time of >65 seconds and a dabigatran plasma concentration of >200 ng/ml (valley) indicating an increased risk of bleeding.

For the factor Xa antagonists, there is a concentration-dependent prolongation of the prothrombin time (PT). In addition, factor Xa activity can be specifically determined using plasma calibrated for the corresponding drug, although direct associations between coagulation parameters and bleeding risk are currently not confirmed (Table 3) [13].

DOAK in renal failure

Chronic renal failure is considered a risk factor for both thromboembolic and hemorrhagic events in patients with VHF [16].

In the absence of clinical data, DOAKs are not used in advanced renal failure (GFR <30 ml/min) according to current ESC guidelines, whereas they appear to be a valid alternative to VKAs in moderately impaired function (GFR 30-50 ml/min) at adjusted doses [17]. Personally, the authors are already cautious above a GFR of 40 ml/min.

In general, patients with impaired renal function taking DOAK should undergo at least six-monthly follow-up visits. Even more common in elderly and polymorbid patients and in risk factors of acute deterioration (e.g., infections, heart failure).

Hemorrhagic complications with DOAK.

Like all anticoagulants, DOAKs carry an increased risk of major bleeding. Specifically, additive antiaggregatory therapy, combination with NSAIDs, and renal dysfunction increase the rate of bleeding. Specific antidotes are not yet available (currently in phase II trials). Experts recommend the administration of activated or regular prothrombin complex concentrate (PKK, e.g. Beriplex®; aPKK Feiba®), as well as activated factor VII (Novoseven®), in addition to the usual, non-specific measures.

If dabigatran is dialyzable, therapeutic hemodialysis is an option (especially in renal insufficiency).

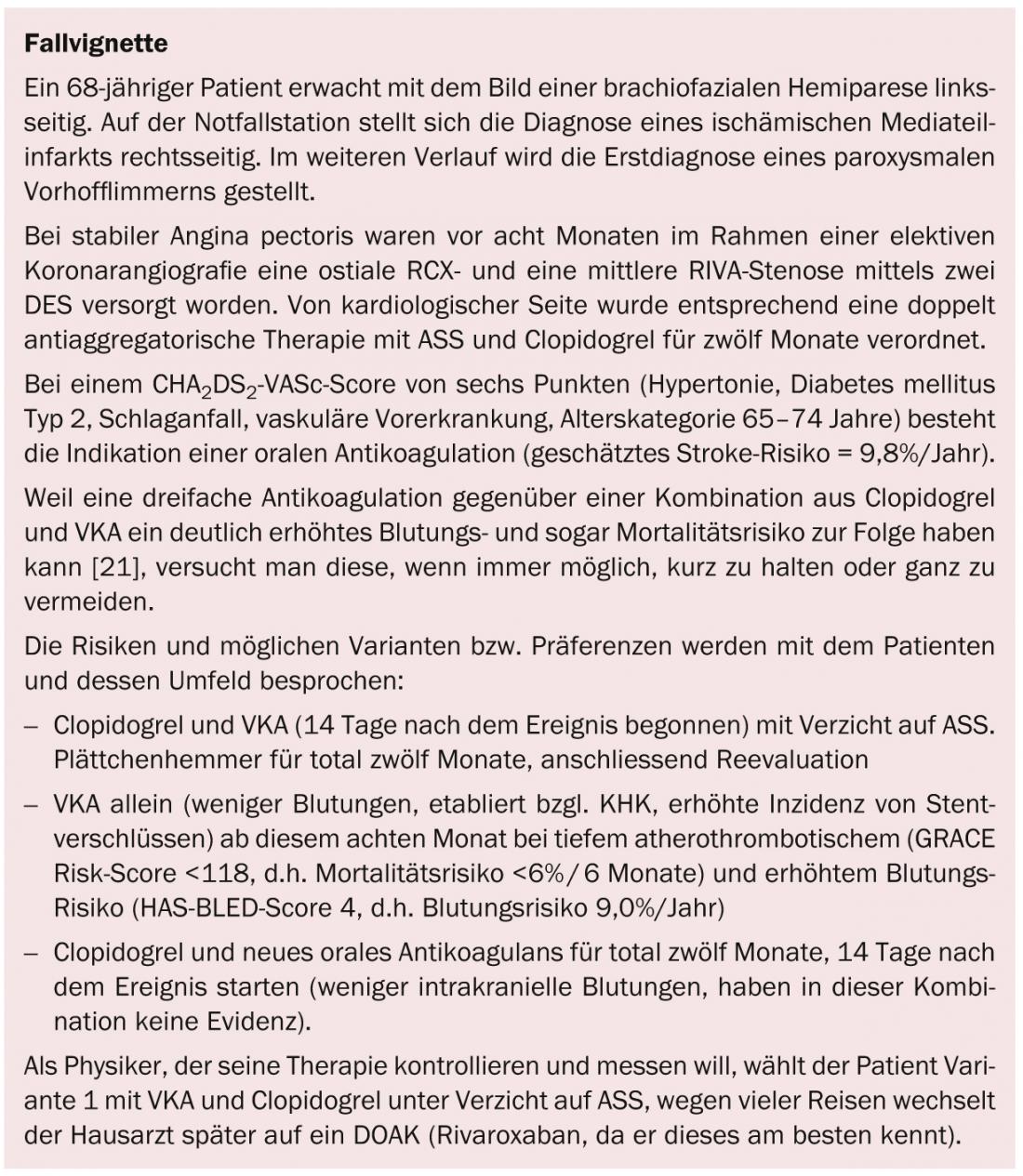

Coronary artery disease and VHF under OAK.

The combination of VCF and coronary artery disease is not only common but also complex and associated with significantly increased mortality [18].

In the acute setting, current guidelines should be followed and OAK should be paused in favor of dual antiplatelet therapy with parenteral anticoagulation.

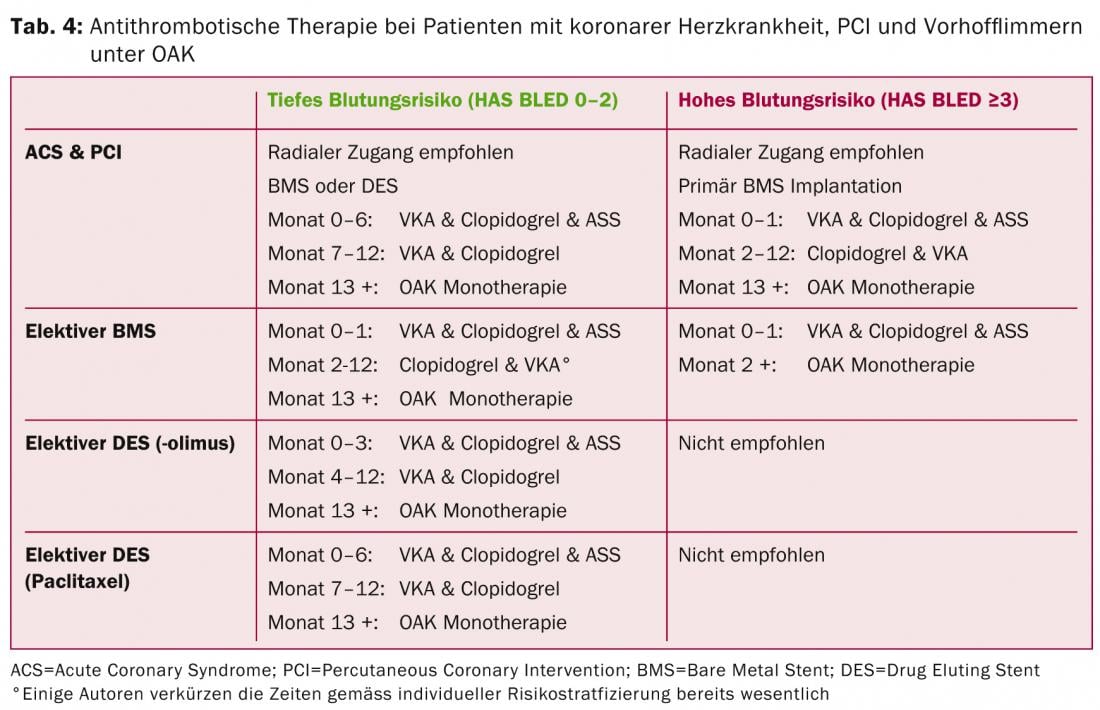

In stable coronary artery disease, the benefit-risk ratio of combination therapy should be evaluated using common scores for thromboembolic (CHA2DS2-VASc), atherothrombotic (GRACE), and bleeding risk (HAS-BLED score).

The basic point to note is that triple therapy with dual antiaggregation and OAK at least doubles the risk of bleeding and should be kept as short as possible [19]. DOAKs are also an alternative to VKAs in combination therapy. The new P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel, ticagrelor) are not recommended in triple therapy because of increased bleeding tendency (exception: clopidogrel allergy, stent thrombosis under clopidogrel). Table 4 provides an overview of the current ESC recommendations in different clinical scenarios [20].

Mechanical heart valves and DOAK

The RE-ALIGN trial compared dabigatran with VKA in patients with mechanical prosthetic valves.

The trial had to be stopped early in phase II after an increased stroke rate (5% vs. 0%) was shown alongside an increased major bleeding rate (4% vs. 2%; HR 1.76, 95% CI 0.37-8.46) [21].

In this sense, VKA remain the only peroral form of anticoagulation in patients with mechanical heart valves.

Conclusions

DOAK are at least equal and in some cases even significantly superior to standard therapy with VKA in non-valvular atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism with regard to safety and efficacy, with a simultaneous halving of the intracranial bleeding risk, and represent a valid alternative to VKA (ESC class IIa recommendation, evidence level A). Routine monitoring of the anticoagulant effect is not required. In case of renal insufficiency, the limits of use must be closely observed. Laboratory monitoring of renal function is recommended annually in patients with preserved function and at least semiannually in those with impaired function (<40 ml/min; formally from GFR 30-60 ml/min). In addition, subgroups such as frail and elderly, oncologic patients, special events (infection, dehydration, heart failure, etc.), increased gastrointestinal bleeding risk, and drug interactions must be kept in mind. With a short half-life of DOAK and thus a high demand for medication adherence, compliance and good instruction are particularly important. All patients should carry a medication card and have clearly defined instructions for use. Further studies with a direct comparison of DOAK and indication testing in additional patient groups (e.g., pediatric and oncologic patients) are important to enable individualized treatment.

Nicole R. Bonetti

Literature:

- Birman-Deych E, et al: Use and effectiveness of warfarin in Medicare beneficiaries with atrial fibrillation. Stroke 2006; 37: 1070-1074.

- Hylek EM, et al: Major hemorrhage and tolerability of warfarin in the first year of therapy among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2007; 115: 2689 -2696.

- Weitz JI, Crowther M: Direct thrombin inhibitors. Thrombosis research 2002; 106: V275 – 84.

- The EINSTEIN Investigators: Oral Rivaroxaban for Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2499-2510.

- The EINSTEIN Investigators: Oral Rivaroxaban for symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1287-1297.

- Agnelli G., et al: Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 799 – 808.

- Lassen MR, et al: Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2487-2498.

- Patel MR, et al: Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 883-891.

- Granger CB, et al: Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 981-992.

- Connolly SJ, et al: Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1139-1151.

- Hohnloser SH, et al: Myocardial ischemic events in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with dabigatran or warfarin in the RE-LY trial. Circulation 2012; 125: 669-676.

- Ruff CT, et al: Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. The Lancet 2013; DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0.

- 13 Heidbuchel H, et al: European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. European Society of Cardiology 2013; doi:10.1093/europace/eut083.

- Mega JL, et al: Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 9-19.

- Alexander JH, et al: Apixaban with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 699 -708.

- Olesen JB, et al: Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 625-635.

- Fox KA, et al: Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism with rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with non valvular atrial fibrillation and moderate renal impairment. Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 2387-2394.

- Lopes RD, et al: Antithrombotic therapy and outcomes of patients with atrial fibrillation following primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the APEX-AMI trial. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 2019 -2028.

- Lamberts M, et al: Bleeding after initiation of multiple antithrombotic drugs, including triple therapy, in atrial fibrillation patients following myocardial infarction and coronary intervention: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation 2012; 126: 1185-1193.

- Freek WA Verheugt: Antithrombotic Therapy During and After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2013; 128: 2058-2061.

- Eikelboom J, et al: Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1206-1214.

CARDIOVASC 2014; 13(2): 5-10