Fingerprinting before entering a foreign country? Quickly unlock your smartphone using fingerprint technology? What seemed self-evident yesterday can become impossible for cancer patients within a very short time. Although the loss of the fingerprint is not one of the dangerous side effects of oncological therapies, it can still lead to problems in daily life.

53-year-old Markus K. suffers from advanced rectal cancer with liver and lung metastases. Under chemotherapy with capecitabine/oxaliplatin, his condition stabilizes to the point that he wants to visit his sister in the U.S. one last time. But then comes the shock: he is refused entry because the quality of his fingerprints is insufficient. Only after consultation with the treating oncologists and much frustration does Markus K. manage to enter the USA despite his declining health. He dies six months later.

Markus K. is not an isolated case; the reason for his disappearing papillary lines is the therapy with capecitabine. However, other chemotherapeutic agents and certain targeted oncologic agents can also lead to loss of fingerprinting (or: phlebotomy). Apart from a few case reports, only a few systematic studies exist on this phenomenon – and these provide quite unexpected results.

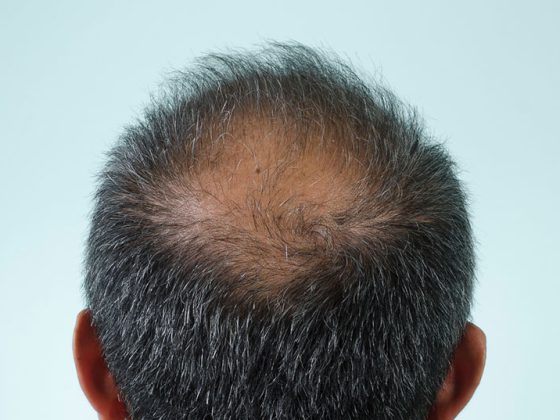

No clear association with hand-foot syndrome

Contrary to the earlier assumption that the loss of papillary lines should be considered a direct consequence of hand-foot syndrome and thus a known chemotherapy side effect, several recent studies conclude that the fingerprint can disappear even without clinical signs[1–3]. Thus, changes in the fingerprint of varying degrees were observed in corresponding studies in almost 70% of patients receiving capecitabine therapy and about 55% of patients receiving paclitaxel treatment – without association to the occurrence of hand-foot syndrome [1,2]. While some study participants developed clinically definite hand-foot syndrome without severe changes in fingerprints, others developed clear changes in papillary lines – without symptoms of hand-foot syndrome such as dysesthesia, swelling, redness, or blistering. Also, in one study, treatment with sunitinib led to a marked decrease in fingerprint quality in one patient without subjective complaints [3]. Unlike hand-foot syndrome, neither dose nor duration of therapy appears to have a clear effect on papillary lines. What effects other substances that can trigger hand-foot syndrome have on the fingerprint cannot be assessed on the basis of the current state of studies. These agents include, for example, doxorubicin, docetaxel, cytarabine, and 5-fluorouracil, as well as small molecule kinase inhibitors such as axitinib, dabrafenib, and sunitinib [4]. In any case, an impairment of the quality of the fingerprints cannot be ruled out.

The bottom line: who gets hit by the uncomfortable condition of drug-induced vein matoglyphics is largely unclear so far. This makes it all the more important to educate potentially affected patients at an early stage – especially those who are being treated with capecitabine or paclitaxel. This is the only way to intercept frustration, apply for the biometric passport before therapy, and change the cell phone lock to facial recognition. Since fingerprint decline is currently only listed in the prescribing information for capecitabine – and even there only as a consequence of hand-foot syndrome – there is an even more important role for practitioners in this regard [5]. The physician is also important in dealing with the little-known adverse drug effect of papillary line loss. Thus, corresponding travel plans can be significantly simplified by a medical certificate.

The good news

Aside from the often asymptomatic course of the fading fingerprint, there is another piece of good news. Indeed, even if there is no clear correlation with clinically manifest hand-foot syndrome, the loss of papillary lines after discontinuation of therapy behaves similarly: it is reversible within weeks after the end of treatment, and permanent damage is rare [3]. However, discontinuation of effective treatment because of asymptomatic choroidal matoglyphia seems quite excessive – another reason for comprehensive patient education.

Literature:

- Yaghobi Joybari A, et al: Capecitabine induced fingerprint changes. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019; 44(5): 780-787.

- Azadeh P, et al: Fingerprint changes among cancer patients treated with paclitaxel. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017; 143(4): 693-701.

- van Doorn L, et al: Capecitabine and the Risk of Fingerprint Loss. JAMA Oncology. 2017; 3(1): 122-3.

- Heyn G: Oncological therapy: targeted prevention of skin damage. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2019. www.pharmazeutische-zeitung.de/hautschaeden-gezielt-vorbeugen.

- Swissmedic drug information: www.swissmedicinfo.ch (last accessed 09.11.2021).

InFo ONcOLOGy & heMATOLOGy