The disease hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa was first mentioned in 1839 with superficial abscesses on the axillary, submammary and perianal regions. To date, the disease has had various names: Perifolliculitis capitis abscendens et suffodiens, Pyoderma fistulans significans, Hidradentitis suppurativa in 1956 by Pillsburg et al. and in 1989 acne inversa by Plewig and Steger. Today, the term hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is again preferred in order to clearly differentiate the disease from acne conglobata and the acne forms. Both terms are recognized as equivalent in the guidelines.

You can take the CME test in our learning platform after recommended review of the materials. Please click on the following button:

The disease was first mentioned by Velpeau in 1839 with superficial abscesses on the axillary, submammary and perianal regions. To date, the disease has had various names: Perifolliculitis capitis abscendens et suffodiens, Pyoderma fistulans significans, Hidradentitis suppurativa in 1956 by Pillsburg et al. and in 1989 acne inversa by Plewig and Steger. Today, the term hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is again preferred in order to clearly differentiate the disease from acne conglobata and the acne forms [1–8]. Both terms are recognized as equivalent in the guidelines. In the article, the term HS will be used as a substitute for both names.

One well-known sufferer of HS was Marx, who gave a very dramatic account of his ordeal and the very typical clinical symptoms of the disease: unpleasant smells, self-loathing, devaluation of self-image, restricted movement, itching, pain, aggression, depression, frustration with doctors, attempts at self-healing, in this case posthumous diagnosis. One gets the impression that little has changed for the patients to date: Suffering, frustration, years until diagnosis [9]. There is still a high unmet need for this disease, both in terms of treatment and acceptance by the general public and, to some extent, the medical profession.

“One disease, many names to date and therefore late diagnosis, late treatment and a lot of suffering for those affected.”

Epidemiology and prevalence

The prevalence is up to 1% (data based on Germany) [10], mean age 23-25 years [11,12], usually with onset after puberty and before menopause. The disease occurs more frequently in women than in men, the male-female ratio is 1:2 to 1:5, except in the anal form, where more men than women are affected [11]. One third of all HS patients report a positive family history. The diagnosis is made with a delay of around 12-15 years [12]. The data still show a wide dispersion, which always indicates that we need further epidemiological studies.

Genetics

The extent to which genetic factors play a role in the pathogenesis of acne inversa has not yet been conclusively clarified. It is striking that HS occurs in families [13]. The disease is probably a multifactorial process based on an individual predisposition. There was consensus among the experts at the 1st International Symposium that, from a genetic point of view, HS must be a polygenetic disease with sporadic cases that either have defects in several important genes that are involved in the pathogenesis of HS or that a defective gene is inherited in the family [13,14]. In a Chinese study, the locus on chromosome 1p21.1-1q25.3 in the 76 Mb region flanked by the markers D1S248 and D1S2711 was assigned to HS [15]. However, this locus could not be confirmed by other groups [16,17]. In a study of six Han Chinese families with familial disease, mutations of the γ-secretase complex on chromosome 19p13 were detected [18]. Based on other studies, HS showed different polymorphisms than Crohn’s disease, indicating that Crohn’s disease with its cutaneous manifestations is distinct from HS [14,19]. In short, there is still much research to be done.

Pathogenesis

There are still many unanswered questions here. There is debate as to whether bacterial colonization per se is the cause or the result of the inflammation. The current theory assumes that bacterial or unconditioned lymphocyte infiltration (perifolliculitis) with pus formation leads to occlusion and dilatation of the follicle and ultimately to rupture of the follicle due to hyperkeratosis and keratin plugging. The rupture leads to deep abscesses and tunnel formation with tissue destruction. The destroyed epithelium forms painful sinus tracts and extensive inflammatory plaques. Extensive scarring is another consequence of the severe deep inflammation [20].

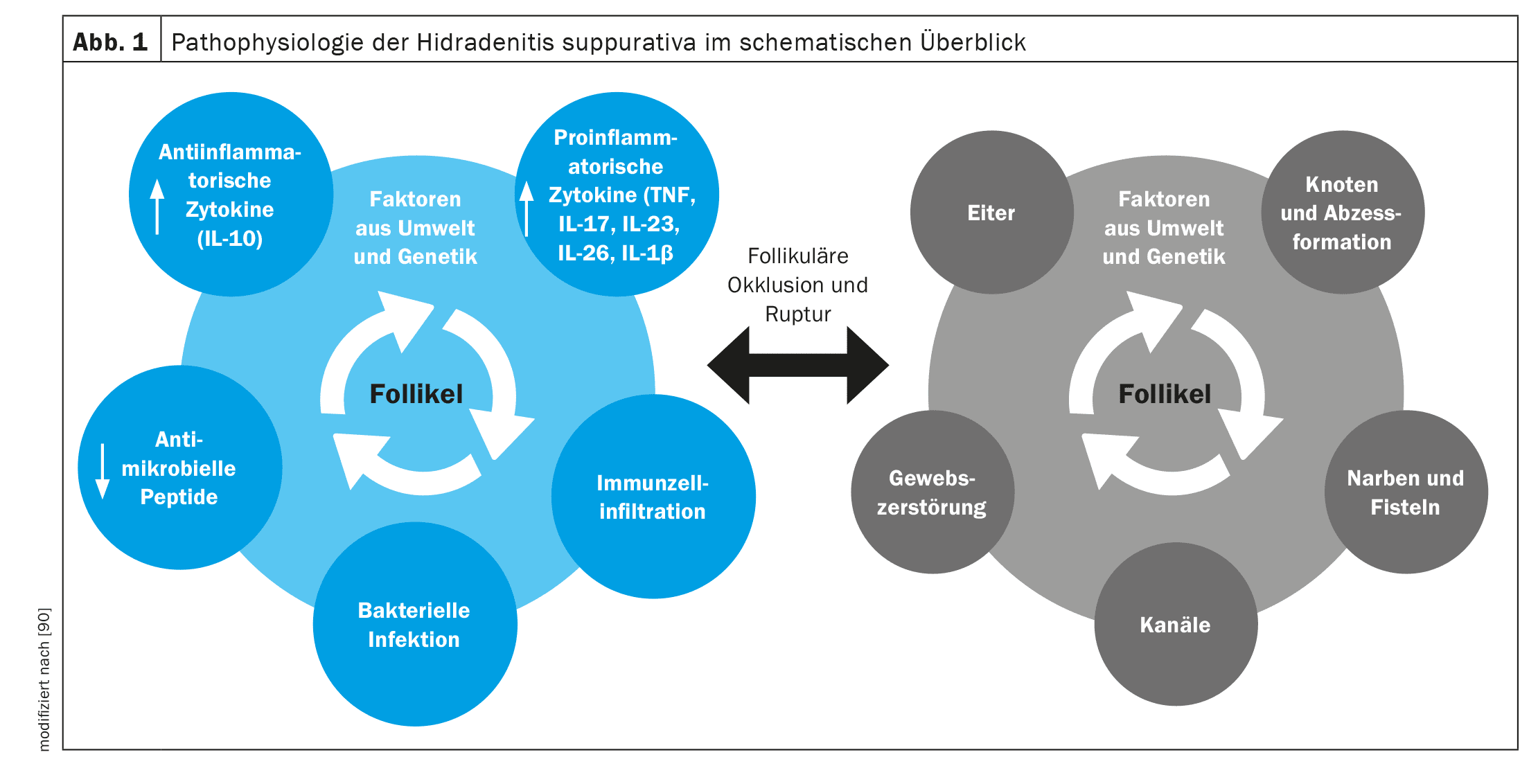

The immunological reaction presumably begins with the occlusion of the follicle triggered by genetic factors (mutations of epsilon-sectretase, PSTPIP1, IL12Rb1) and environmental factors such as obesity and smoking. Prior to follicular rupture, the follicle dilates and inflammatory pathways (e.g. TH17, TNF alpha, IL-17, IL-32) are triggered and release pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β, IL-17A, TNF, IFN-γ, CXCL-8, IL-8, IL-17, IL-32, IL-36a/b/g, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70). These cytokines potentially stimulate keratinocytes to form abscesses. In addition, a decrease in the expression of IL-20 and IL-22 has been demonstrated in skin lesions of patients with HS [21,22]. Ultimately, the immunological and inflammatory processes lead to the typical clinical picture with recurrent abscesses with characteristic tunneling and scarring [23-25].

A 16-week s.c. therapy with the anti-TNF-α drug adalimumab resulted in the inhibition of cytokine expression, particularly of IL-1β, CXCL9 (MIG) and BLC, and the decrease in the number of CD11c+ (dendritic cells), CD14+ and CD68+ cells in lesional skin [26]. The IL-23/Th17 signaling pathway is stimulated in hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa [27] (Fig. 1).

Bacteria

HS is not primarily an infectious disease of the skin [28,16]. Nevertheless, a large number of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria have been detected in hair follicles in the affected region, most frequently S. aureus, Peptostreptococcus species, Propionibacterium acnes as well as Escherichia coli, Proteus and Klebsiellen [29]. Over time, the percentage of NK cells (natural killer cells) decreases and a reduced response of monocytes to bacterial components is observed. Compared to normal skin, the number of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2-expressing infiltrating macrophages (CD68+) and dermal dendrocytes (CD209+) increased in HS lesions. TLR-2 is stimulated by bacterial products and has a pro-inflammatory effect. It is assumed that this can lead to changes in the defense against bacterial infections, e.g. through a weakened response of monocytes to inflammatory stimuli, but further studies must show whether this is really the case.

Furthermore, an altered expression of antimicrobial peptides was found, such as the overexpression of psoriasin in the lower layers of the epidermis, whereas the expression level of human β-defensin-2 (hBD-2) was reduced in the epidermis. In contrast to normal skin, monocytes/macrophages expressing hBD-2 were also found in the subepidermal dermis. This could be due to an increased expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and the detected activation of TLR receptors [30]. The increased expression of C-type lectin receptors, which play a role in the antigen presentation of macrophages and dendrites, suggests an interaction of TLR with C-type lectin receptors as a trigger of chronic inflammation in HS [30]. Recently, a strong expression of cathelicidin (LL-37) has been detected in the apocrine sweat glands, which could be associated with the pathogenesis of HS [31,32].

Clinic

Early signs are pruritus, local hyperthermia, hyperhidrosis, painful subcutaneous nodules, bacterial colonization is rare [33,34]. The primary lesion is a painful, solitary, deep-seated, cutaneous-subcutaneous nodule that may regress spontaneously, persist or transform into an abscess. The abscesses may fuse in depth or rupture outwards. In contrast to acne, the deep parts of the follicle are affected. Later, the deep-seated inflamed nodules lead to abscesses, fistulas and/or scarring. The armpits, inguinal region, perianal region, gluteal region, perineum and submammary region are affected. The course is chronically recurrent.

The disease usually manifests symmetrically and almost exclusively in the apocrine inverse areas [35,36]. The axillary region is most frequently affected with 72%. Women show a different distribution pattern than men. In women, the axillae, the submammary region and the inguinal region are often affected, whereas in men the anogenital and retroauricular region, the neck and the perineum are often more affected [37–39]. Around 90% of patients also develop a pilonidal sinus [40,41]. Spontaneous healing is not to be expected.

Risk factors

89% of patients are smokers [42]. Nicotine presumably causes occlusion of the hair follicles [43], but is also considered a cofactor for a poorer prognosis of inflammation in psoriasis.

There are indications of a genetic disposition and in this case autosomal dominant inheritance [44], 34% of first-degree relatives have the same symptoms [45]. Gene mutations such as those in the secretase gene (Notch signaling) probably also play a role [45], see the genetics section for more information.

A high body mass index increases the odds ratio by 1.126; 77% of men are overweight, 26% are obese, 69% of women are overweight, 33% are obese [46]. Here, the latest data from AAD 2024 also showed that both bariatric surgery and GLP-1 agonist administration resulted in a better response or a reduction in HS, regardless of whether type 2 diabetes mellitus was present or not. Similar data have also been reported in psoriasis, providing clear evidence that the inflammatory insulin resistance that develops due to inflammation plays a significant role in the obesity/inflammation vicious cycle and that these patients simply cannot lose weight without breaking the insulin resistance [47].

Trigger factors

Some of the triggers and risk factors are the same. The recognized trigger factors for HS include smoking, obesity, inflammation of the hair follicles, bacterial colonization – particularly with Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) -, genetic predisposition, regional hyperhidrosis and mechanical irritation [28].

Hormones

Premenstrual relapses of HS are common in about 40% of patients, often with improvement at the onset of menopause.

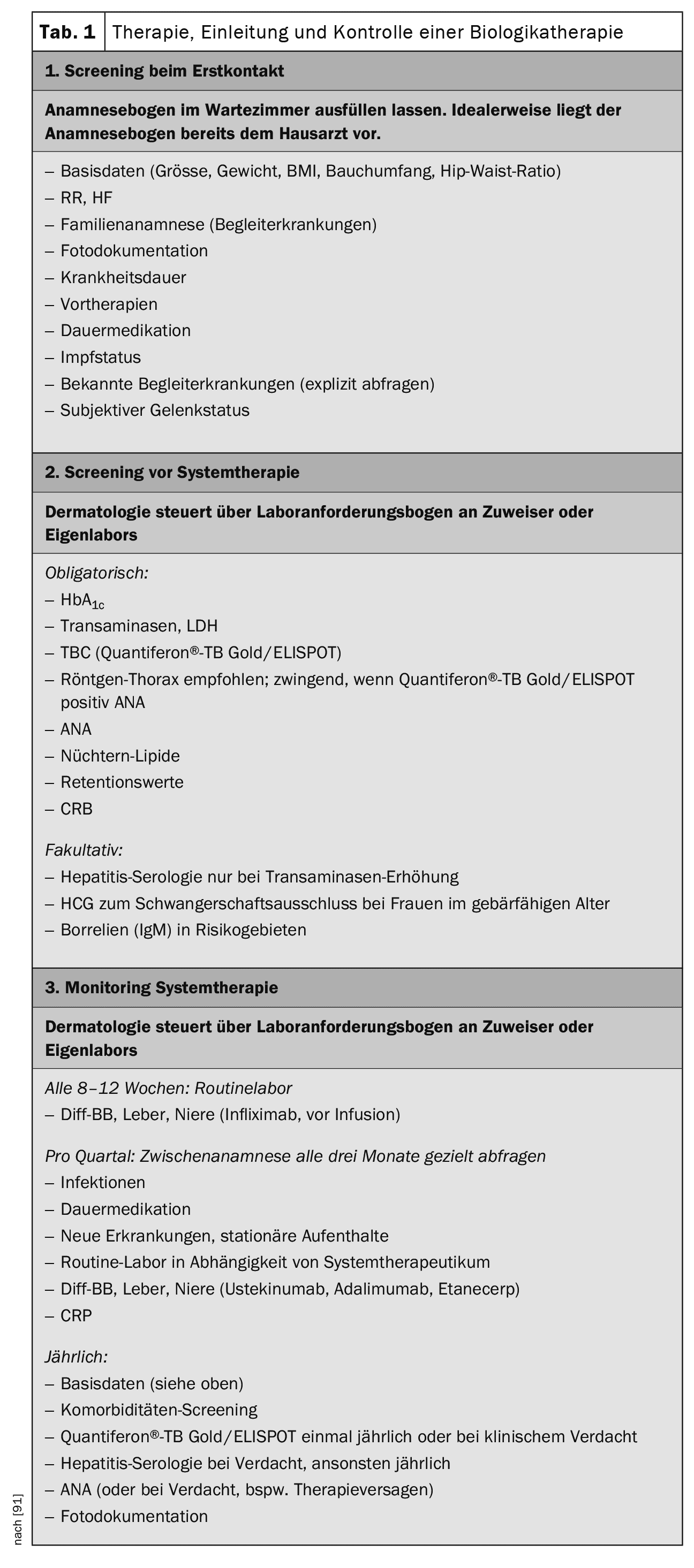

The influence of hormonal factors, in particular androgens, on the development of the disease is still the subject of controversial debate. In contrast to acne vulgaris, their influence is probably not as significant [48,49]. Female patients with HS should be examined promptly for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and insulin resistance [50] (Tab. 1).

Comorbidity and psychosocial consequences of the disease

HS has a high comorbidity with metabolic syndrome (40-51%) [51,52], type 2 diabetes mellitus (9-30%) [53,54], inflammatory bowel disease (1-13%) [51,55,26], Crohn’s disease (1-17%), ulcerative colitis (1-9%), spondyloarthropathies (2-28%) [51,56] and psychiatric disorders (5-36%) [51,53,57]. These comorbidities are also found in other highly inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis and COPD and, in my view, are a comorbidity of inflammation and speak for the severity of inflammation in HS. Comorbidity with inflammatory bowel diseases, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and spondyloarthropathies, involves common pathways and we also see this in other inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis. Specific comorbidities are PCO syndrome with 9-14% [53,58] and squamous cell carcinoma, especially in the anal region, with 5% [57,59].

The psychological consequences are characterized both by the inflammation (neuroinflammation) and by the considerable psychosocial consequences of the disease: stigmatization, shame, sleep disorders, isolation, depression, anxiety disorders and even suicide, sexual dysfunction, subastanzabusus. Aggravating factors are pain, itching, secretion, odor and restricted movement [60].

The high comorbidity has consequences. On average, hidradentitis patients die 14.7 years earlier. Leading causes of death are cardiovascular diseases, cancer and accidents/violence (incl. suicide, increased especially in women), a study from Finnish health registers showed in 4379 patients with HS compared with 40,406 patients with psoriasis vulgaris and 49,201 with melanocytic nevi [61].

The loss of working hours and restrictions at work are considerable, only 53.3% of patients are fully employed and only 25.8% have no restrictions at work due to their illness [62] (Table 1). The limitation of quality of life (DLQI) correlates with: Pain, severity, number of body sites involved, disease duration and progression [63]. Other influencing factors are odor development, anxiety, social isolation and restriction and amount of movement [64–67]. Patients with HS therefore have an even greater impairment of quality of life than other severe inflammatory dermatological diseases such as psoriasis vulgaris.

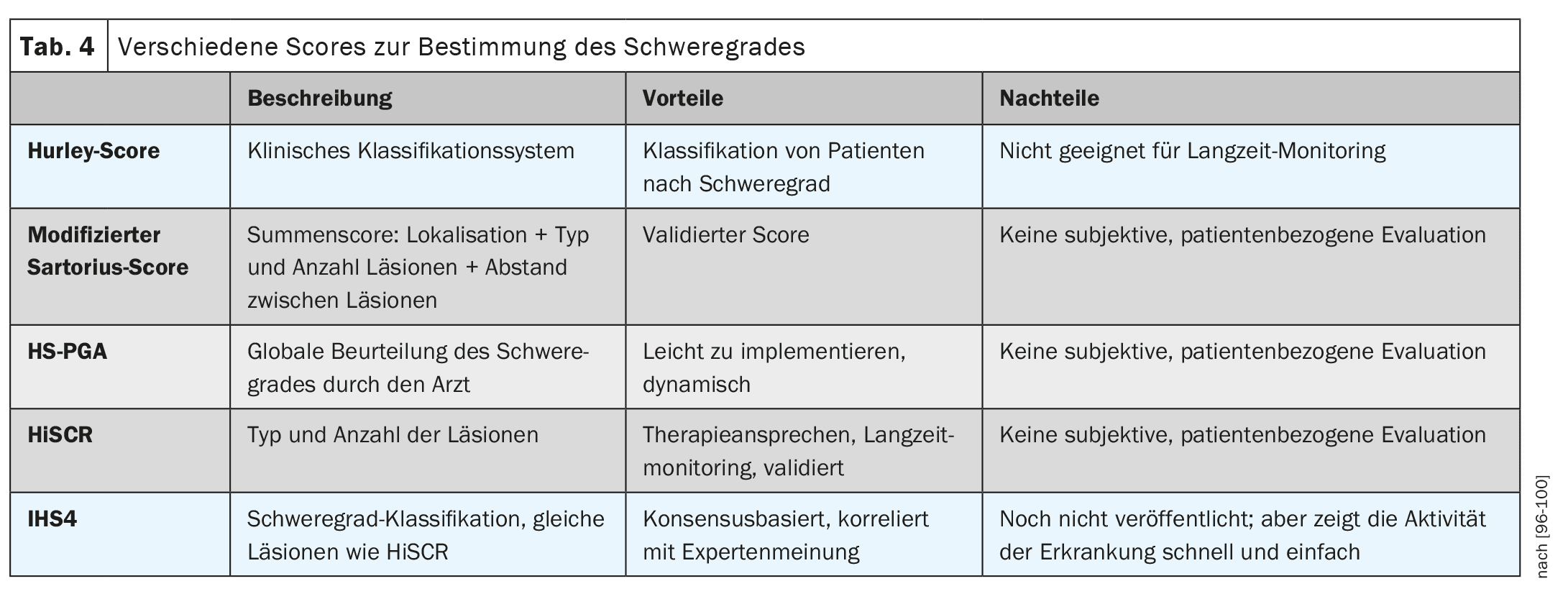

Severity of the disease and scores

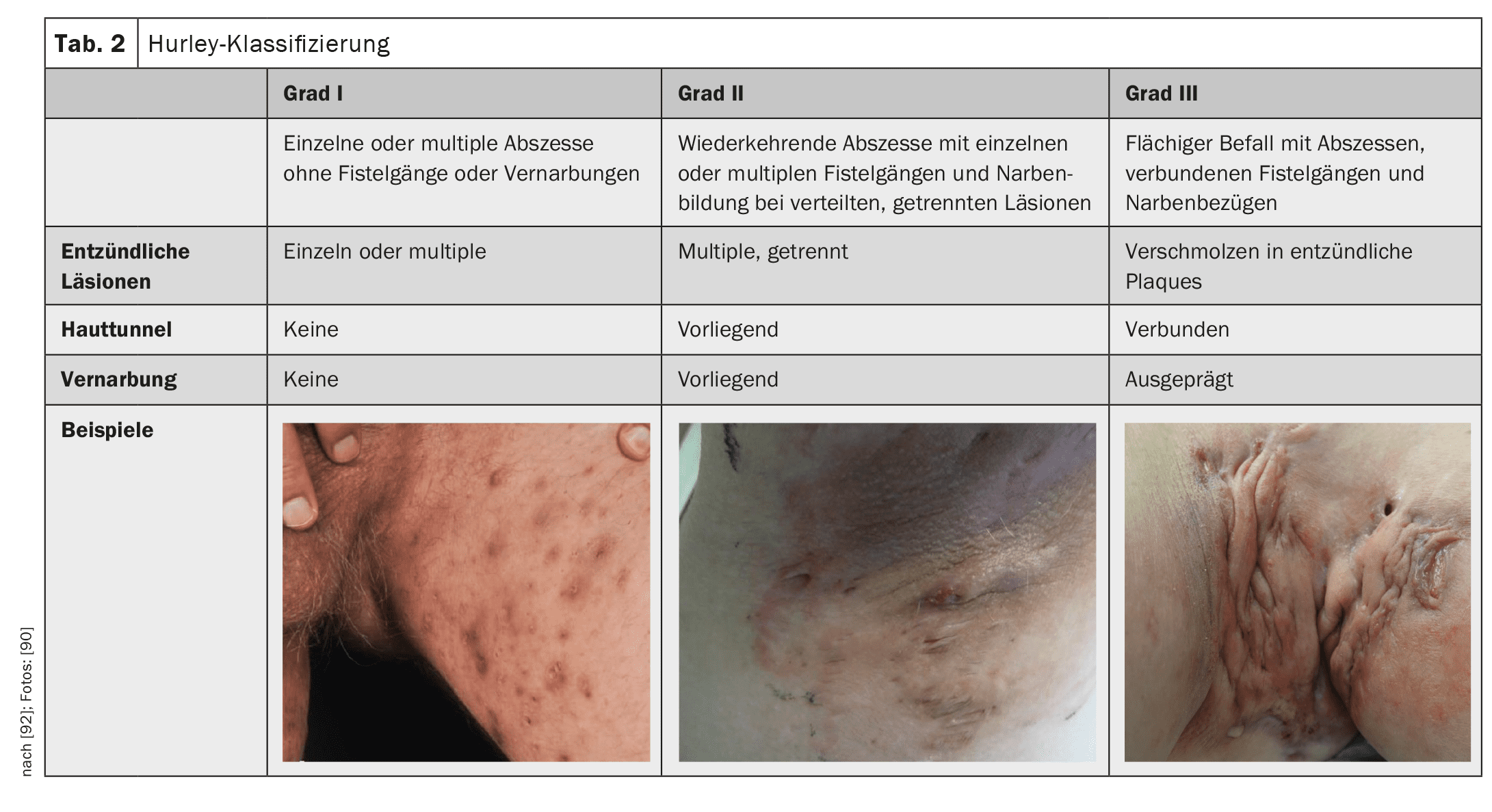

The severity of the disease is classified according to Hurley grade 1-3 (Table 2). The HS-PGA (Physician Global Assessment for HS) – less precise but faster – is another way of determining severity. Here, the examiner rates the severity as appearance-free, mild, moderate or severe, which is quicker, but is also a much more individualized, less objective assessment. The Hurley Score or the HS-PGA is used to classify the severity of the disease, which then determines the further therapy, not the activity of the disease.

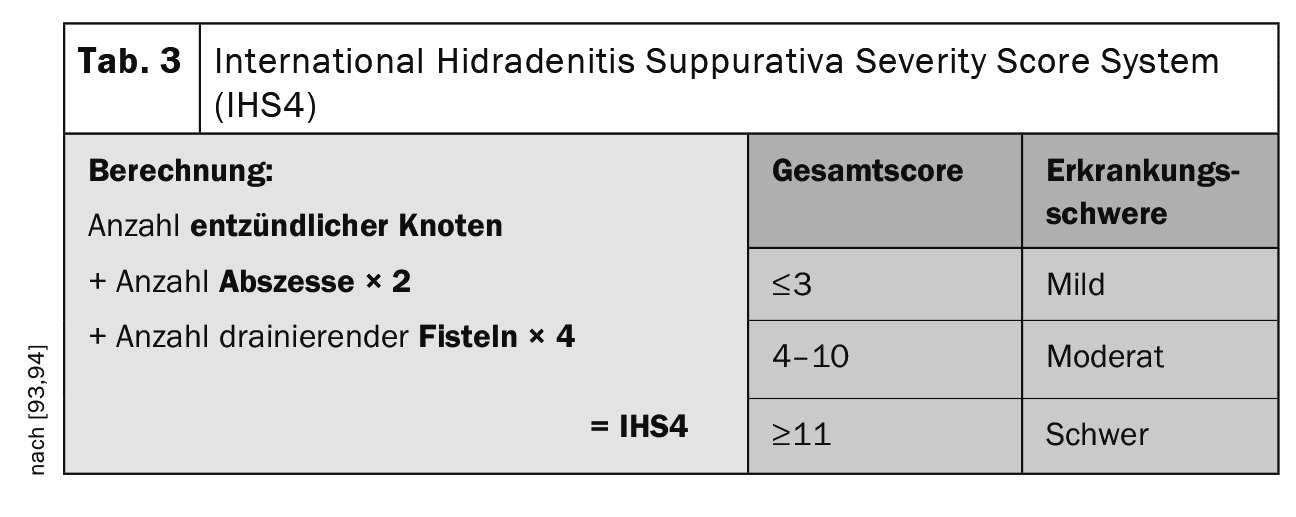

Scores such as the IHS4 (number of inflammatory nodules + number of abscesses ×2 + number of fistulas ×4) are used to determine the activity of the disease (Table 3). Patient-related scores are the DLQI (Dermatology Life Quality Index) known from other diseases or the HiSQOL or the Ool-HS (scores even more specifically tailored to HS) [68–70].

In my opinion, the most important scores in everyday practice are the determination of severity according to Hurley 1-3, the IHS4 and the DLQI and photos. In severe forms, sonography (preferably 3D) can also be useful; often the sinus tracts and “pus lakes” under the skin cannot even be guessed at [71] (Table 4).

Diagnostics and laboratory tests

- Family history survey positive in 30% [72],

- Question about tobacco consumption,

- Survey of the BMI,

- Clinical examination by inspection, palpation and, if necessary, fistula probing,

- Determination of BOD and CRP. Elevated blood sedimentation and C-reactive protein indicate an acute deterioration.

- Bacteriological smears: If a superinfection is suspected, smears must be taken from deep affected tissue areas and not from the skin surface alone.

- Examinations with a high-resolution ultrasound device [73] or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful in determining the depth of expansion.

Therapy

Treatment depends on the severity of the HS and is based on the Hurley 1-3 classification (Table 2).

Lifestyle modification

Weight reduction (hardly possible without a change in diet and attention to inflammatory insulin resistance) and smoking cessation (difficult, as this is often associated with weight gain for patients who are often already overweight and is therefore a further psychological and physical burden). Avoid friction and irritation factors by wearing loose clothing made of soft, naturally sweat-absorbing fibers. Partially absorbent powders are recommended against the trigger factor sweating and avoidance of massive sweating (how should the patient then do sport?). Dietary approaches with reduction of the glycemic index of the diet (insulin resistance!). Nutritional supplements such as zinc and copper are also recommended in some cases [74,75].

Many of our often well-intentioned lifestyle modification tips are often not so easy for patients to put into practice; they not only need our help and support, but also our tolerance and empathy.

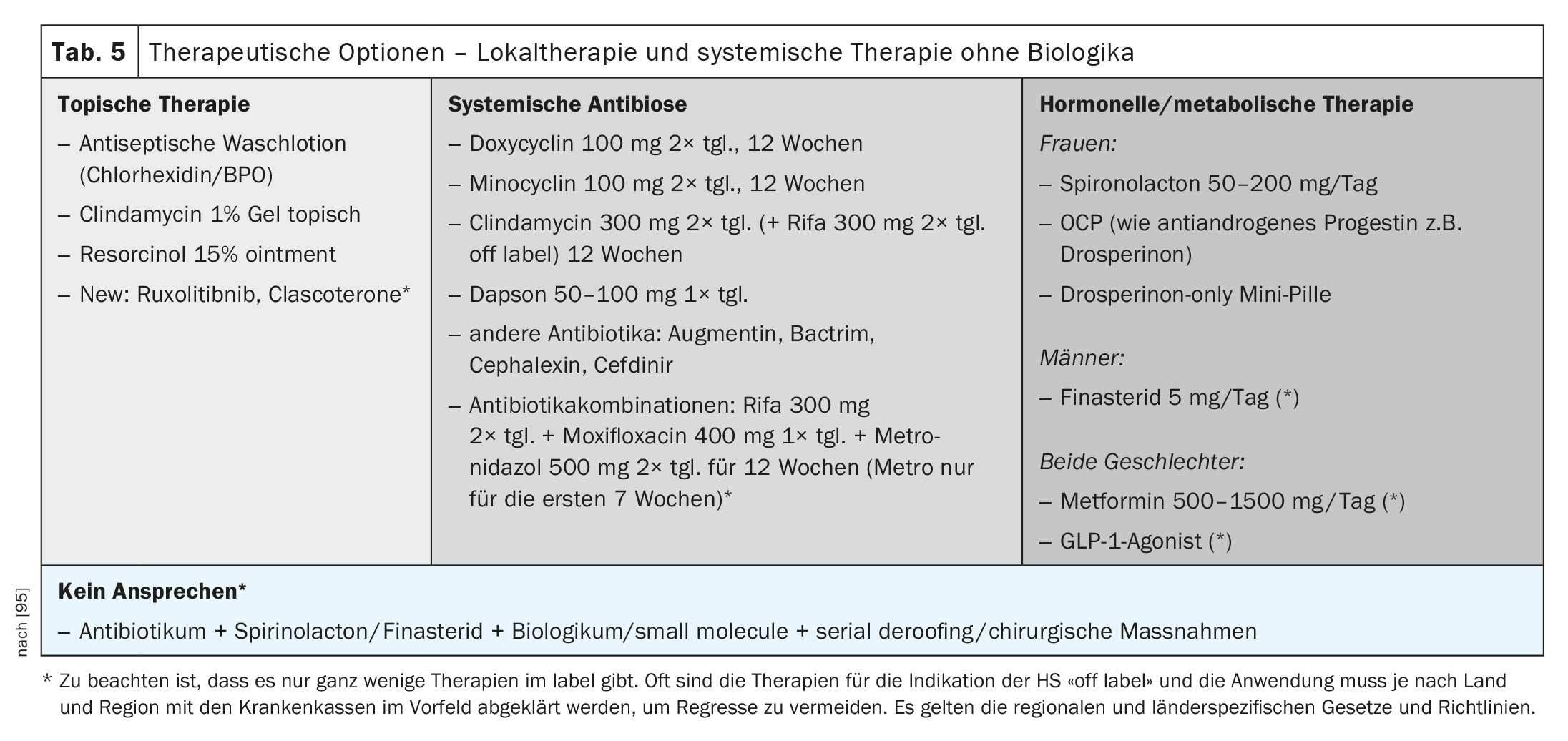

Local therapy

Local treatment with antiseptic washes and local antibiotic therapy is particularly useful in the early stages of HS (Table 5).

Laser therapy/light therapy

For hair removal in the early stages in hairy areas with the Nd: YAG or alexandrite laser [76,77] or the Laight therapy, a combination of IPL + radio frequency [78–82], are to be seen as a useful addition to the therapy, but are often not reimbursed.

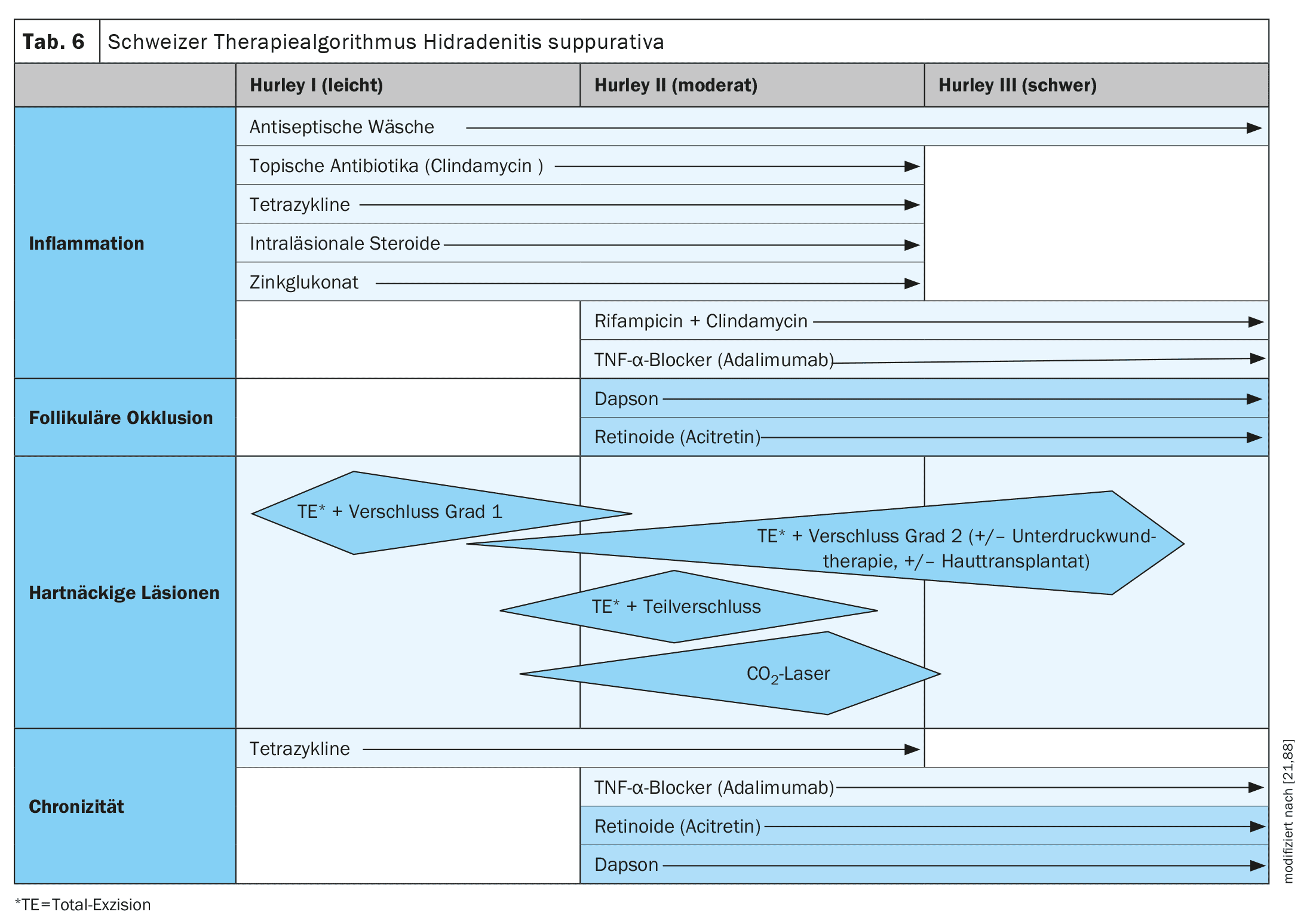

System therapy according to severity (Hurley/guideline)

The guidelines vary slightly from country to country. Although the Swiss guideline has minor deviations, it is closely based on the German and European S3 guideline (Table 6).

Systemic antibiosis

There are only a few approved antibiotics for the treatment of HS, and the therapies recommended in the guidelines are not always on the label (Table 5). Nevertheless, they are useful in stage-appropriate use and are usually the first form of systemic therapy.

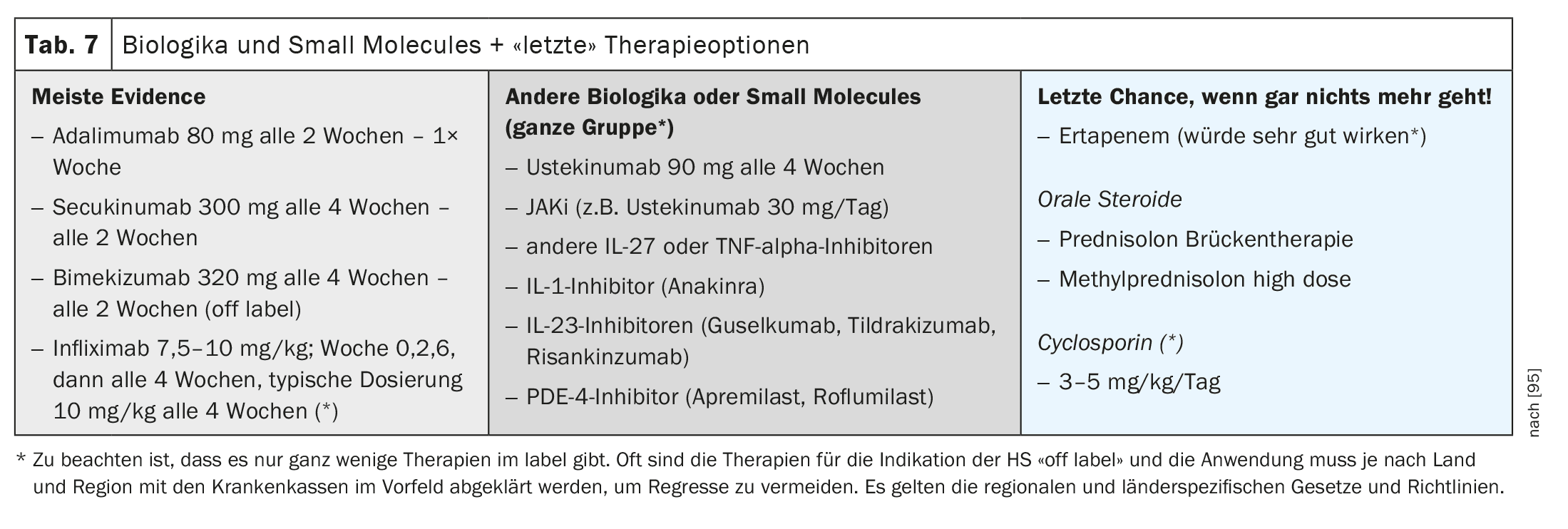

Biologics, small molecules and more (Table 7)

There are currently only three approved biologics: adalimumab (TNF alpha inhibitor), secukinumab (IL-17 AA inhibitor) and bimekizumab (IL-17 AA/AF/F inhibitor). All other biologics are either still in registration studies or can only be used off-label. The so-called “small molecules” such as apremilast (PDE4 inhibitor) have not yet been approved.

Insulin sensitizer

There are now studies for both metformin and the new GLP-1 receptor antagonists that show an independent effect of these drugs on HS by breaking insulin resistance and having anti-inflammatory effects [83–87].

Laboratory value controls

The recommendations for biologics therapy in psoriasis can be used for laboratory value checks before and during therapy (Table 1).

Pregnancy

For pregnancy, the otherwise binding approval restrictions and the information in the prescribing information and the Embryotox registry also apply. Only the TNF-alpha inhibitors adalimumab (on label) and certolizumab-pegol (off label for HS) are actually possible here with conditional approvals for pregnancy as in psoriasis vulgaris. Good information for patients and their partners is essential.

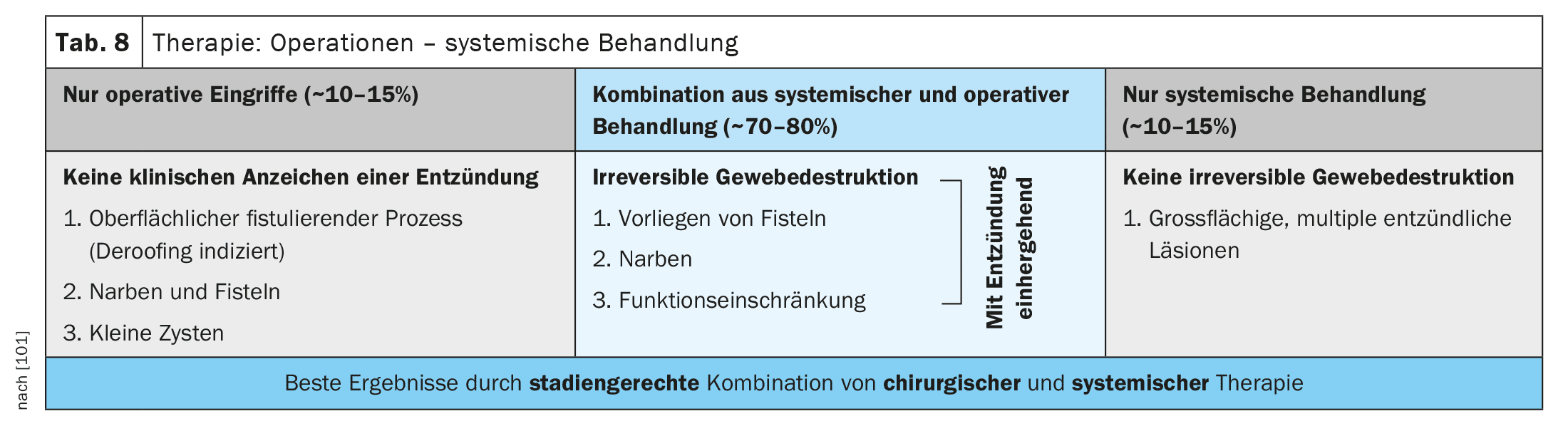

Surgical therapy

Surgical treatment should be seen as a therapeutic option or as a supplement to treatment at all stages. This can range from the individual removal of cysts, so-called deroofing (opening of the abscess cavity with a 6-punch or scalpel), through to the complete treatment of entire areas, depending on the stage (Table 8).

The best results can be seen in a stage-appropriate combination of medical and surgical therapy.

Pain therapy

In my view, there is a very high unmet need here . At the AAD 2024 in San Diego, an entire presentation was dedicated to this point and a step therapy for the treatment of pain was developed (Table 9).

As with all chronic pain patients, the treatment of pain already leads to a considerable improvement in the quality of sleep and life. Sleep, in turn, is also an absolute co-factor in the improvement of depression in depressive patients. This can also be seen in urticaria with a high rate of completed suicides, although there is generally less inflammation here than in HS, but insomnia due to the agonizing itching.

Conclusion and challenges for practice

New therapy options are available in addition to the known local therapies, antibiotic therapies and approved biologics such as adalimumab and its biosimilar and the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and bimekizumab. Many therapy options that would be possible are still off-label and therefore have to be applied for. Nevertheless, the current care situation is challenging, with delayed diagnoses, incorrect diagnoses and the wrong specialist preventing early, stage-appropriate therapy.

Inadequate disease control over an extremely long period of illness leads to destroyed skin with irreversible damage and comorbidity. The internal and psychological comorbidity and social stigmatization lead to a high level of absenteeism from work and a life expectancy that is significantly reduced by years for these patients. Scores and questionnaires help to find the right treatment options, but cost time that we often don’t have in everyday practice.

“Hit hard and early”: Here too, early intervention can prevent or minimize permanent damage and prevent disease progression and comorbidity. In my view, pain therapy is another major unmet need. Interdisciplinary cooperation in therapy is essential, networks are still lacking

My personal wish for the patients and also for us doctors:

- In order to cover the high unmet need in the treatment and care of these really severely affected patients, further medication and the promotion of self-help groups and therapy support measures, also outside of medical care, are an absolutely desirable goal.

- Early start of treatment through early diagnosis and awareness of all doctors involved in the process and close cooperation (dermatologists, gynecologists, surgeons, general practitioners, emergency room physicians, patients and associated healthcare professionals and wound care centers).

- Guideline-based and future-oriented care through reimbursement of the drugs specified in the guidelines and, in severe cases, uncomplicated approval of off-label use therapy in accordance with the current study situation and data. And not just for HS, but for all orphan diseases and severe inflammatory diseases.

- Adjusting payment for the care of these complex patients for practices so that they can take the time to provide care.

Take-Home-Messages

- New treatment options are available in addition to the well-known local therapies, antibiotic therapies and approved biologics such as adalimumab and its biosimilar and the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and bimekizumab.

- Nevertheless, the current care situation is challenging, with delayed diagnosis, incorrect diagnosis and the wrong specialist preventing early, stage-appropriate treatment.

- Inadequate disease control over an extreme disease duration leads to destroyed skin with irreversible damage and comorbidity.

- The internal and psychological comorbidity and social stigmatization lead to a high level of absenteeism and a life expectancy that is significantly reduced by years for these patients.

- Interdisciplinary cooperation in therapy is essential, networks are still lacking.

Literature:

- Velpeau A: In: Dictionnaire de Médecine, un Répertoire Général des Sciences Médicales sous la Rapport Théorique et Practique2nd ed, Vol. 2. Bechet Jeune, 1839; 91.

- Verneuil A: Arch Gén Méd 114: 537-557.

- Hoffmann E: Dermatol Z 1908; 15: 120-135.

- Kierland RR: Minn Med 1951; 34: 319-341.

- Pillsbury DM, Shelley WB, Kligman AM: Dermatology.1st ed.

- Pillsbury DM, et al: Bacteria infections of the skin. Dermatology 1956; 482-484.

- Plewig G, Kligman AM: Acne. Morphogenesis and Treatment. Springer 1975; 192-193.

- Plewig G, Steger M. In: Marks R, Plewig G.: Acne and Related Disorders 1989; 345-357.

- Thadeusz F: Medicine: New blood in the womb. Der Spiegel 51/2007

- Kirsten N: Arch Dermatol Res 2021; 313(2): 95-99.

- Sabat R, Jemer G, Matusiak L, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa. Nature Reviews Disease Primer 2020; 6: 18.

- Kokolakis: Dermatology 2020; 236(5): 421-430.

- Williams HC, Raeburn JA: The clinical genetics of hidradenitis suppurativa revisited. Br J Dermatol 2000; 142: 947-953.

- Fimmel S, Zouboulis CC: Comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). Dermatoendocrinol 2010; 2: 9-16.

- Gao M, Wang PG, Cui Y, et al: Inversa acne (hidradenitis suppurativa): a case report and identification of the locus at chromosome 1p21.1-1q25.3. J Invest Dermatol 2006; 126: 1302-1306.

- Sellheyer K, Krahl D: What causes acne inversa (or hidradenitis suppurativa)? – the debate continues. J Cutan Pathol 2008; 35: 701-703.

- Hurley HJ: Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa and familial benign pemphigus. Surgical approach. In: Dermatologic Surgery. Principles and Practice (Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH Jr, eds)2nd edn. New York 1996; 623-645.

- Wang B, Yang W, Wen W, et al: Gamma-secretase gene mutations in familial acne inversa. Science 2010; 330: 1065.

- Nassar D, Hugot JP, Wolkenstein P, Revuz J: Lack of association between CARD15 gene polymorphisms and hidradenitis suppurativa: a pilot study. Dermatology 2007; 215: 359.

- Saunte: JAMA 2017; 318(20): 2019-2032.

- van der Zee HH, Laman JD, de Ruiter L, et al: Adalimumab (anti-TNF-α) treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa ameliorates skin inflammation: an in situ and ex vivo study. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 298-305.

- Wolk K, Warszawska K, Hoeflich C, et al: Deficiency of IL-22 contributes to a chronic inflammatory disease: pathogenetic mechanisms in acne inversa. J Immunol 2011; 186: 1228-1239.

- Vossen: Front Immunol 2018; 14: 2965.

- Fletcher: Clin Exp Immunol 2020; 201: 121-134.

- Napolitano: Clin Cosmetic Invest Dermatol 2017; 10: 105-115.

- Egeberg: J Invest Dermtol 2017; 17: 1060-1064.

- Schlapbach C, Hönni T, Yawalkar N, Hunger RE: Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 790-798.

- Jansen T, Altmeyer P, Plewig G: Acne inversa (alias hidradenitis suppurativa). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001; 15: 532-540.

- Lapins J, Jarstrand C, Emtestam L: Coagulase-negative staphylococci are the most common bacteria found in cultures from the deep portions of hidradenitis suppurativa lesions, as obtained by carbon dioxide laser surgery. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140: 90-95.

- Emelianov VU, Bechara FG, Gläser R, et al: Immunohistological pointers to a possible role for excessive cathelicidin (LL-37) expression by apocrine sweat glands in the pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. Br J Dermatol 2011.

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Antonopoulou A, Petropoulou C, et al: Altered innate and adaptive immune responses in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 51-56.

- Hunger RE, Surovy AM, Hassan AS, et al: Toll-like receptor 2 is highly expressed in lesions of acne inversa and colocalizes with C-type lectin receptor. Br J Dermatol 2008; 158: 691-697.

- Alikhan A, et al: JAAD 2009; 60: 539-561.

- Jackman RJ: Proc R Soc Med 1959; 52(suppl): 110-112.

- Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, Wolkenstein P, et al: Clinical characteristics of a series of 302 French patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, with an analysis of factors associated with disease severity. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 61: 51-57.

- Poli F, Wolkenstein P, Revuz J: Back and face involvement in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology 2010; 221: 137-141.

- Sabat: Dermatologist 2017; 68: 999-1006.

- Saunte: JAMA 2017; 318(29): 2019-2032.

- Benhadou: Deramtoly 2021: 237; 317-319.

- von Laffert M, Stadie V, Wohlrab J, Marsch WC: Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: bilocated epithelial hyperplasia with very different sequelae. Br J Dermatol 2011; 164: 367-371.

- Jemec GB, Gniadecka M: Sebum excretion in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology 1997; 194: 325-328.

- Satorius: Br J Dermtol 2009; 161(4): 831-839.

- König: Dermatology 1999; 198(3): 261-264.

- Von der Werth: Br J Deramtol 2000; 142(5): 947-953.

- Jemec: N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 158-164.

- Alikhan: J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60(4): 539-561.

- Murina A: Combining Systemic Therapies: Should You Do it? & Porter M: What’s New in Biologics and Small Molecules for HS. AAD Annual Meeting, San Diego 2024.

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen D: Hidradenitis suppurativa: A comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60: 539-561.

- Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Ju Q, et al: New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol 2009; 18: 821-832.

- Von der Werth JM, Jemec GB: Morbidity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, Br J Dermatol 2010; 144: 809-813.

- Cartron: Int J Womens Deramtol 2019; 5: 330-334.

- Jancin B.: Hidradenitis Suppurativa Linked to Metabolic Syndrome; www.mdedge.com/clinicianreviews/article/79681/endocrinology/hidradenitis-suppurativa-linked-metabolic-syndrome; accessed on 4.6.2024.

- Garg: J Am Acad Deramtol 2020; 82: 366-376.

- Alikhan: J. Am Acad Deramtol 2019; 81: 79-90.

- Principi: World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22: 4802-4811.

- Rondags: J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 551-554.

- Chapma: Acta Deramtolvenerol APA 2018; 27: 25-28.

- Garg: J Invest Deramtol 2018; 138: 1288-1292.

- Tzellos: Deamtol Ther 2020; 10: 63-71.

- Tiri: Br J Deramtol 2019; 180(6): 1543-1544.

- Kirten: Dermatologist 2021; 72: 651-657.

- Schneider-Burrus: Br J Dermatol 2023; 188: 122-130.

- Wokenstein P, et al: J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56: 621-623.

- Matusiak L, et al: J Am Acad Dermatol 2010; 62: 706-708.

- Matusiak L, et al: Acta Derm Venerol 2010; 90(3): 264-268.

- Vasquez BG, et al: J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133: 97-103.

- Kurekt A, et al: J Dtsch Deramtol Ges 2013; 11(8): 743-750.

- Finlay: Clin Exp Dermatol 1994; 19: 210-216.

- Kirby: Br J Deramtol 2020; 183(2): 340-348.

- Kirsten: EADV 2021; Poster P0056.

- Wortmann: Dermatol online J 2013; 19(6): 18564.

- Jemec GB: The sympathology of hidradenitis suppurativa in women. Br J Dermatol 1988; 119: 345-350.

- Wortsman X, Jemec GB: Real-time compound imaging ultrasound of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Surg 2007; 33: 1340-1342.

- Grimstad, et al: Am J Clin Derm 2020; 21(5): 741-748.

- Mollinelli, et al: JAAD 2020; 83(2): 665-667.

- Fortoul, et al: Annals of Plastic surgery 2023; 91(6): 758-762.

- Mollinelli, et al: JAAD 2022; 87(3): 674-675.

- Elatif, et al: Intensepulselightversus benzolyperoxide 5%gel in treatment of acne vulgaris. LasersMedSci 201; 29(3): 1009-1015.

- Kawana, et al: Effect of Smooth Pulsed Light at 400 to 700 and 870 to 1,200 nm for Acne Vulgaris in Asian Skin. Dermatol Surg 2010; 36(1): 52-57.

- Taylor, et al: Intense pulsed light may improve inflammatory acne through TNF-α down-regulation. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2014; 16(2): 96-103.

- Min, et al: Comparison of fractional microneedling radiofrequency and bipolar radiofrequency on acne and acne scar and investigation of mechanism: comparative randomized controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol Res 2015; 307: 897-904.

- Yu, et al: Use of a TriPollar radio-frequency device for the treatment of acne vulgaris, J Cosmet Laser Ther 2011; 13: 50-53.

- Verdolini, et al: JEADV 2013; 27(9): 1101-1108.

- Petrasca, et al: Br Journal Deramtol 2023; 189(6): 730-740.

- Jennings, et al: Br Journal Dermatol 2017; 177(3): 858-859.

- Henry, et al: Invest Journal Dermatol 2023; 62(12): 1543-1544.

- Gu, Sebaratnam: Invest Journal Dermatol 2024; 28.

- Hunger RE, et al: Swiss Practice Recommendations for the Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa/Acne inversa. Dermatology 2017; 233(2-3).

- Savage KT, et al: Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. JAAD 2021; 187-199.

- Scala E, et al: Hidradenitis Suppurativa: Where We Are and Where We Are Going. Cells 2021, 10, 2094. www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/10/8/2094# (last accessed 5.6.2024).

- von Kiedrowski R, et al: Psoriasis vulgaris – a practical treatment pathway. Dermatol 2011; 9.

- Zouboulis CC, et al: Dermatology 2015; 231(2): 184-190.

- Zouboulis C, et al: Br J Dermatol 2017; 177, 1401-1409.

- Tzellos T: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2023; 37(2): 395-401.

- Hsiao J: Recalcitrant HA: What to do Next? AAD Annual Meeting, San Diego 2024.

- Kimball AB, et al: Br J Dermatol 2014; 171(6): 1434-1442;

doi: 10.1111/bjd.13270. - Kimball AB: Ann Intern Med 2012; 157: 846-855. (HS-PGA)

- Revuz J: Ann Dermatol Vernol 2007; 134: 173.

- Hurley HJ: Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and familial benign pemphigus: surgical approach. Dermatologic surgery. New York: Marcel Dekker 1989: 39.

- Zouboulis CC, et al: Development and validation of the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4), a novel dynamic scoring system to assess HS severity. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177(5): 1401-1409; doi: 10.1111/bjd.15748.

- Bechara F: Lecture Hidradenitis suppurativa; EADV 2017.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2024; 34(4): 6-15