In chronic pain, various diagnostic, therapeutic, and expert opinion aspects are of great importance. A careful physical status is still very important. Pain models as a communicative bridge in the doctor-patient relationship are helpful for both sides. A therapeutic multimodal approach is essential. The article explains the importance of psychosocial factors for the subjective experience of pain and the course of diseases with chronic pain, the classification and diagnosis of chronic somatoform pain, important insurance-relevant aspects and a clarification algorithm for the assessment of disability in cases of long-term incapacity to work in the context of chronic pain.

Along with fatigue and dizziness, pain is the most common symptom seen by primary care physicians. As defined by the 1979 ISAP, an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience is one that is associated with actual or potential tissue damage or is described in terms of such damage. Pain leads to significant limitations in fulfilling professional and family obligations. The annual prevalence for idiopathic chronic pain in the general population is approximately 10%. Pain is always subjective; tissue damage need not be obligatory [1].

Definition of chronic pain

A chronic pain experience exists when pain persists beyond the usual healing period after unsuccessful treatment attempts [1]. A lowered pain threshold and impairments on a biological, psychological and social level are the result. Frequently, there is no clinical substrate detectable by instrumentation. Generalization and extension to additional dysfunctions are typical. G. L. Engels’ 1977 biopsychosocial model of disease provides a suitable approach for diagnosis and therapy. A comprehensive anamnesis and diagnosis in a trusting atmosphere are a prerequisite.

Peripheral pain is differentiated from central pain. After tissue damage (e.g., a cut), peripheral pain impulses are transmitted centrally via designated nerve pathways and can be experienced as pain sensations. After healing, pain impulses and, in parallel, central pain perception subside. In the case of so-called central pain, the cause lies in the CNS from the outset. Central neuropathic pain is distinguished from central somatoform pain. Central neuropathic pain develops in about 10% of patients after a cerebrovascular insult or stroke. 50% after spinal cord injury, central somatoform pain occurs, for example, as fibromyalgiaform complaints or after a long history of torture.

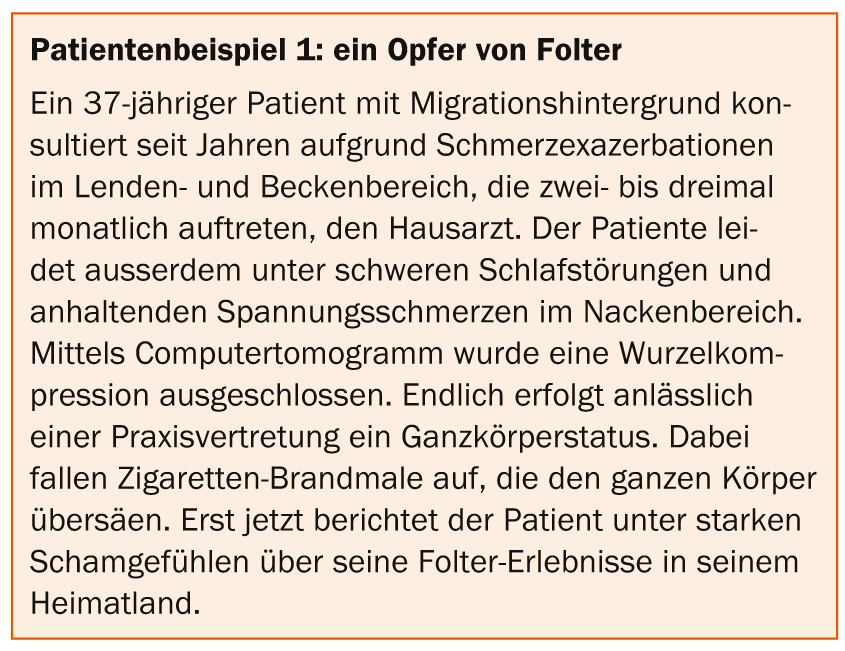

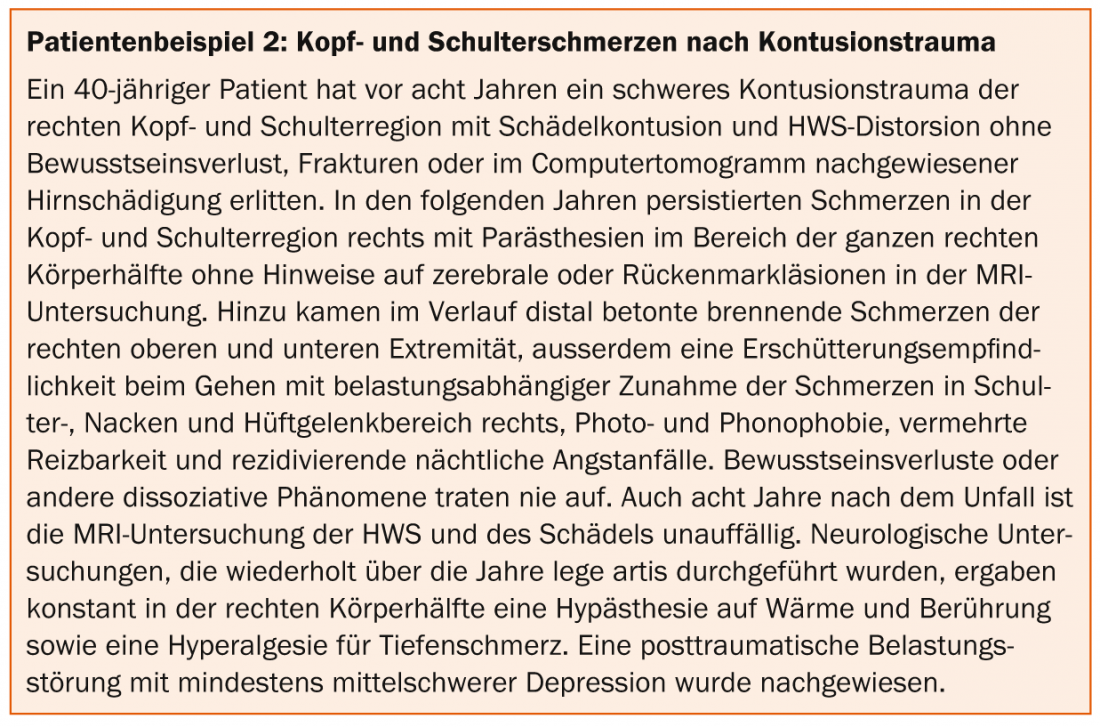

In central somatoform pain, at most only minor structural changes can be detected, but in some studies there is clear evidence of functional changes [2] (patient examples 1 and 2) . About two thirds of all patients with chronic pain after trauma and often consecutive post-traumatic stress disorder and depression develop functional hemisensory disorders with non-dermatome-related ipsilateral thermo- and touch hypoesthesia. The disorder must be actively sought clinically and is by no means hysterical in nature. A complex dysregulation pattern in the somatosensory and limbic cerebral pain matrix is hypothesized.

Pain models

Patients with chronic central pain often request an explanation from their treating physicians and also feel compelled to justify their complaints to their social environment. Over the course of medical history, the conception of the origin of chronic central pain has expanded. Five pain models are briefly outlined below:

- In the 17th century, at the time of René Descartes, it was assumed that after peripheral tissue damage, nerve impulses transmitted to the brain would interact with an immaterial spirit, resulting in a corresponding pain sensation (interactionist substance dualism).

- At the beginning of the last century, additional factors were already influencing pain perception (e.g., psychological stress), as Freud outlined in his theory of conversion pain [3].

- The gate control theory indicated an inhibition resp. The pain impulses in the spinal cord are regulated depending on how far the body keeps the “pain gate” open or closed [4]. Peripheral pain impulses in skin, muscles, joints, and internal organs may be amplified at the level of nociception, innervated in the second pain neuron at the posterior horn, or innervated in the thalamus and sensory cortex resp. be modified by influences of the limbic system. This pain model is well suited to explain neuropathic pain or the effects of acupuncture, hypnosis, autosuggestion, or placebo. The theory also makes it easy to understand why pain is often perceived less in severe acute injuries, or rather, why pain is perceived less in severe acute injuries. current mood states and sleep duration also influence the perception of pain. The gate-control theory also underlies the central mechanism of action of opioid analgesics.

- The bio-psycho-social model fundamentally assumes a central nervous disposition and holds somatosensory stimulus amplification responsible for inter- and intraindividual differences in pain perception [5]. Subjective perception of psychological stress, cognitive interpretation of pain, and influences of neighboring associated brain areas have unequal effects on pain pathways.

- The current valid human scientific view of pain causation is based on the so-called pain matrix [6]. This primarily refers to primary and secondary somatosensory cortex (S1 and S2), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and insula, which are involved in subjective pain perception, as demonstrated in numerous hemodynamic, clinical, neuroelectrical, and neurochemical studies. Not to be forgotten in patient care, however, are individual pain models, which should be inquired about in each patient in a patient-centered manner, using open-ended questioning and active listening in all diagnostic and therapeutic steps [7].

Influence of psychosocial factors

Numerous studies demonstrate a greater influence of psychosocial factors on the intensity and course of chronic pain than the structural damage itself. Workplace stress, couple conflict, and negative childhood memories are more important than structurally underlying spinal damage in the chronification of low back pain [8]. The intensity of osteoarthritis pain is predominantly dependent on daily stress, personality factors, and socioeconomic status. Depressive moods or assumptions about causes of pain are more decisive for the subjective perception of pain than tumor size and metastases.

Classification and diagnosis of chronic pain

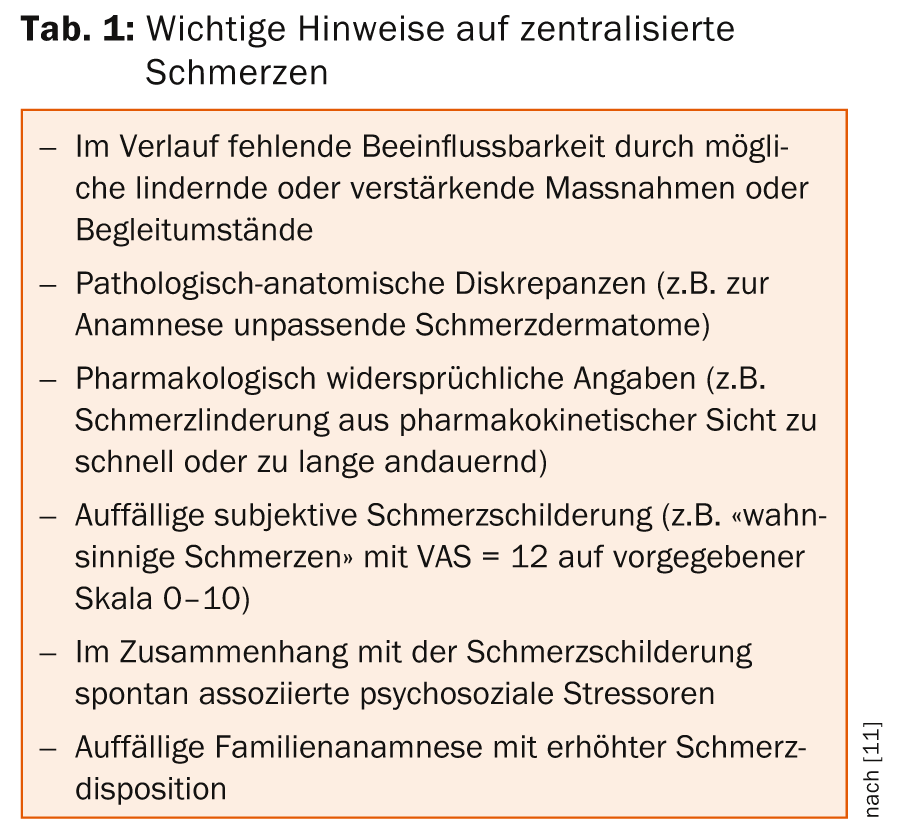

A semistructured biopsychosocial interview and a careful physical examination are indispensable for diagnosis. This provides important clues for the diagnosis and classification of centralized pain (Table 1) .

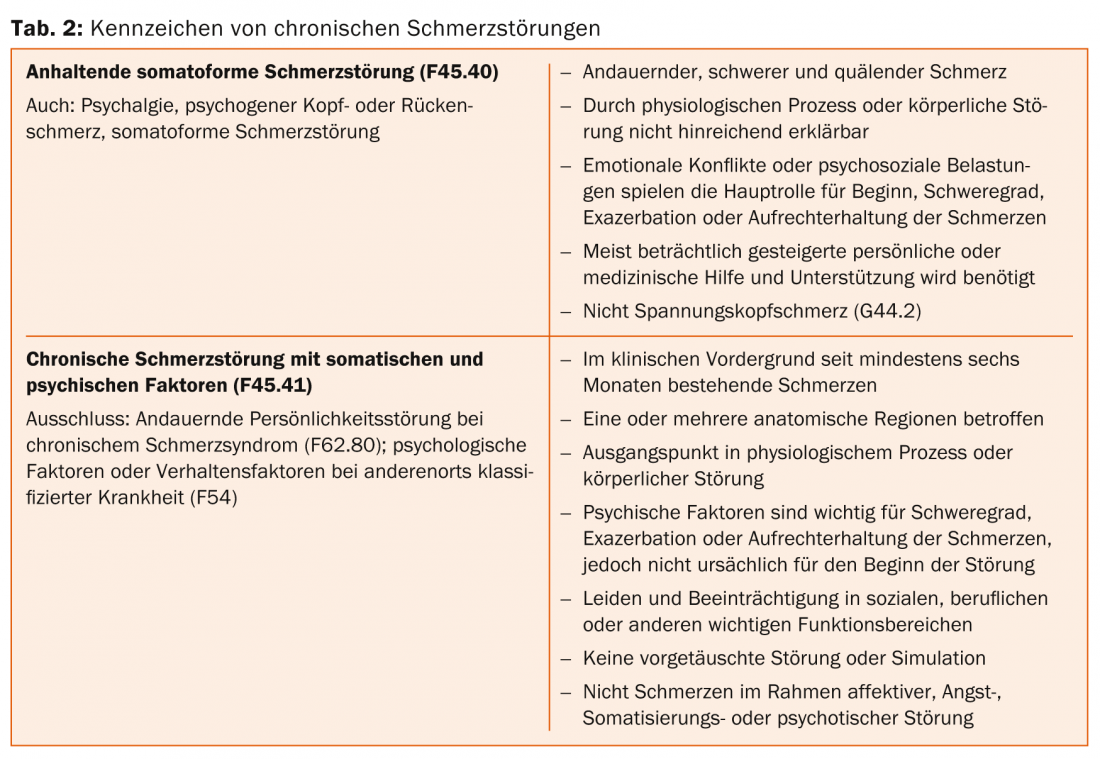

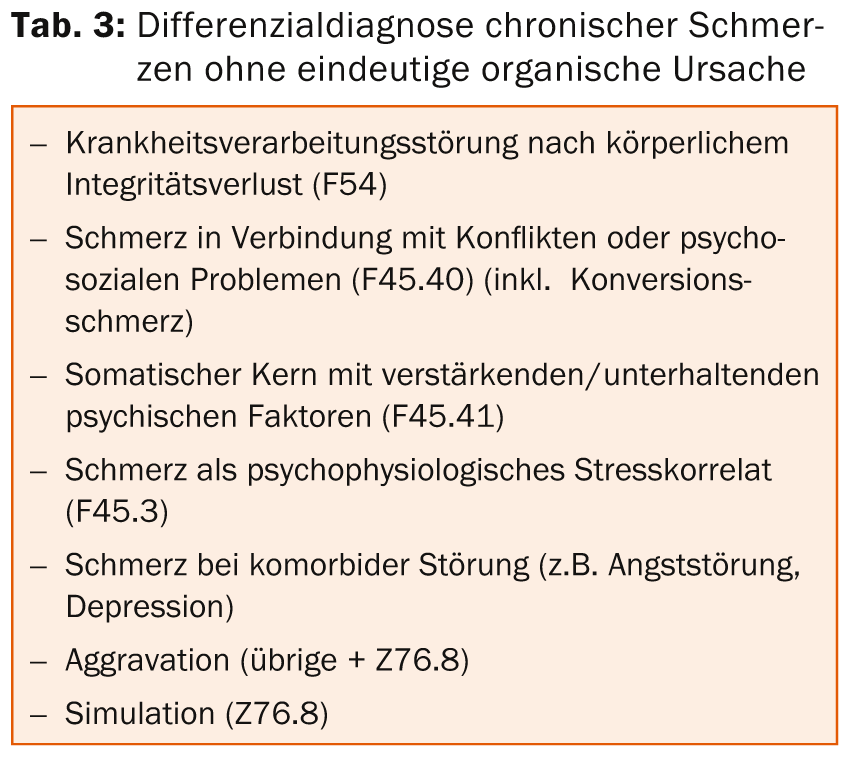

Chronic pain conditions without a clear organic cause are shown in the ICD-10 under F45. Since 2009, they have been grouped under the diagnosis “Persistent pain disorder F45.4” if they are not caused by physiological processes or by the patient’s own pain. can be explained by an organic disorder (F45.40) or somatic factors are causative but psychological factors are also involved (F45.41) (tables 2 and 3).

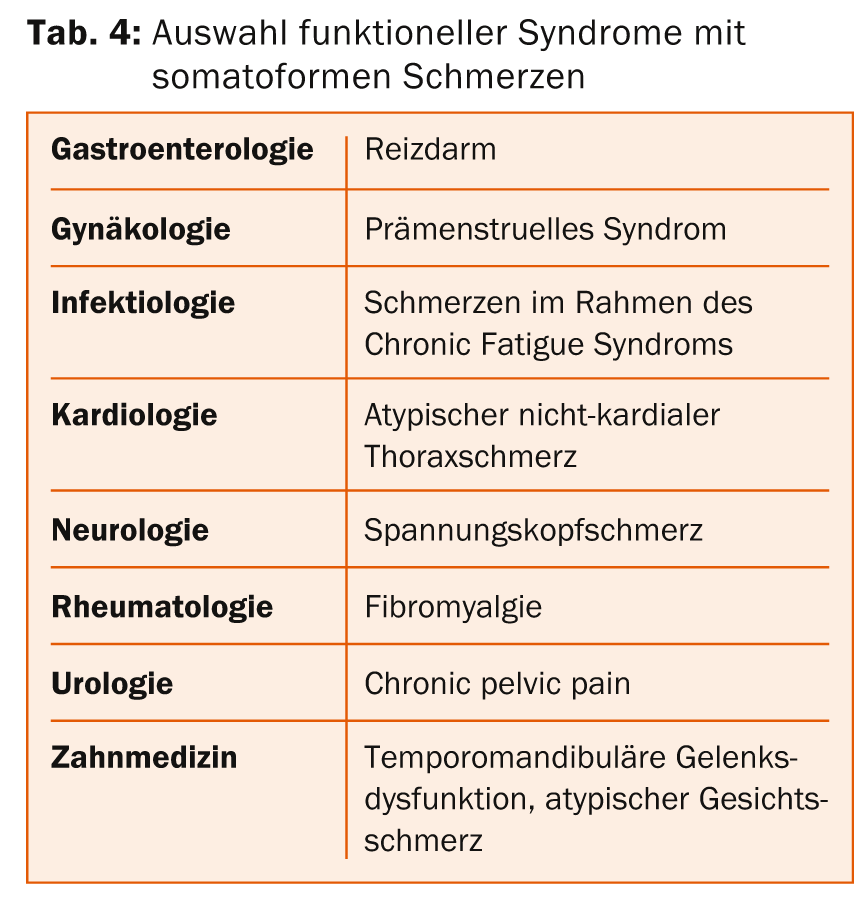

Patients with pain that is not clearly organically caused are often also managed by specialists in medical subspecialties. This often defines a functional pain syndrome (Table 4).

It is not uncommon for chronic pain to be mistakenly considered a substitute for depression. The term somatoform is not considered useful by primary care providers providing care, nor is it accepted by patients. The equally common term “medically unexplained symptoms” implies a body-mind dualism that is bought with expensive investigations and involves the risk of iatrogenic complications. The DSM-5 accepts the permanent interaction between psycho-emotional and physiological-physical factors with the new diagnostic entity “Somatic Symptom Disorder” (SSD). Patients with a primarily somatic illness and additional psychological symptoms should thus be more likely to find access to suitable therapy services. Appropriate training and continuing education programs to identify indications of mental disorders requiring focused psychotherapeutic treatment are increasingly being used and further expanded (SIWF).

Therapeutic access

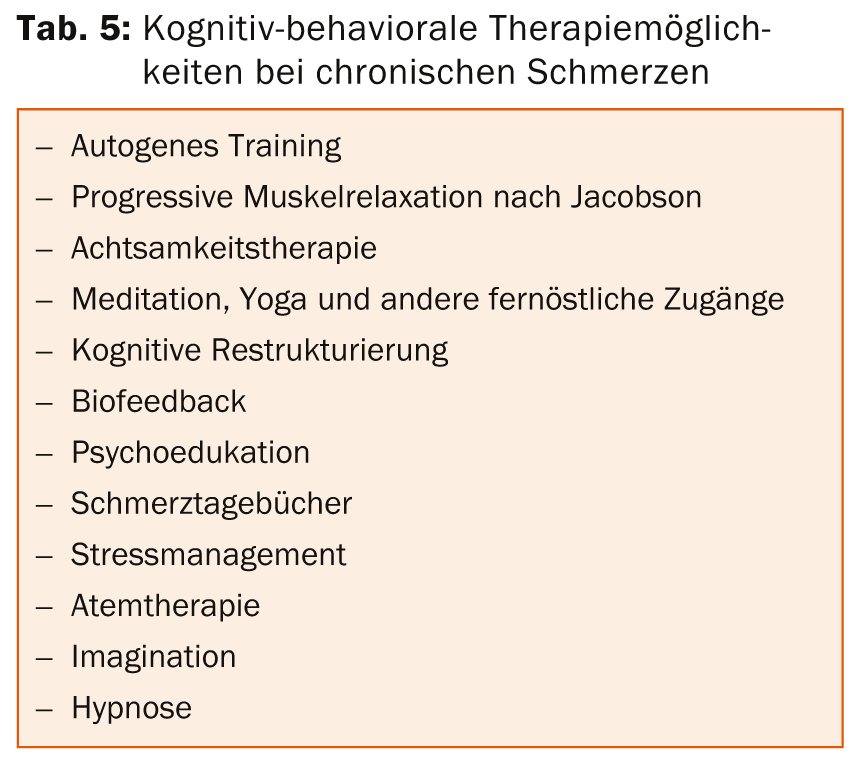

Chronic pain is addressed in designated treatment units using a multimodal approach. Various specialists, psychologists, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social counselors and special therapists work together on an interdisciplinary basis. Evidence-based pain medications are used, as well as agents for sleep regulation and treatment of comorbid psychiatric conditions. Psychotherapeutically, cognitive-behavioral methods are usually used [9]. The systemic involvement of relatives, employers or other important caregivers can be additionally useful, for example, to work on secondary illness gain and collusive relationship patterns. Psychodynamically oriented therapy can address internal stressors and conflicts (Table 5).

Ultimately, all psychotherapeutic measures aim at avoiding negative pain-maintaining assumptions and replacing “disaster scenarios” with realistic assumptions. Indications for structural resp. functional changes after psychotherapeutic interventions have also been demonstrated in imaging studies. Specifically, we work out which internal and external trigger stimuli trigger or intensify pain. Psychiatric concomitant diseases of chronic pain syndromes must be considered in the treatment, especially depression, anxiety disorders, addictive disorders, post-traumatic stress and personality disorders.

Appraisal and insurance-relevant aspects

Chronic pain patients must be taken seriously in their subjective experience. Actively inquiring about how explorants deal with functional limitations and about their disease model is mandatory. With an impartial, critical but empathic attitude, a complete exploration of physical and psychological symptoms is carried out by an interdisciplinary team of medical specialists, coordinated by an experienced specialist. In the end, the latter takes the lead in critically evaluating all findings, checking them for consistency, summarizing them after extensive study of the files, and assessing the causality between objective findings and subjective experience, taking into account the course of events.

Pain can basically be divided into three groups according to expert opinion:

A) Pain as an accompanying symptom of tissue damage (e.g., injury-related).

B) Pain with tissue damage and concomitant mental illness (e.g., persistent pain disorder with physical damage and perpetuating psychological factors).

C) Pain as a leading symptom of mental illness (e.g., cenesthesias in schizophrenic psychosis).

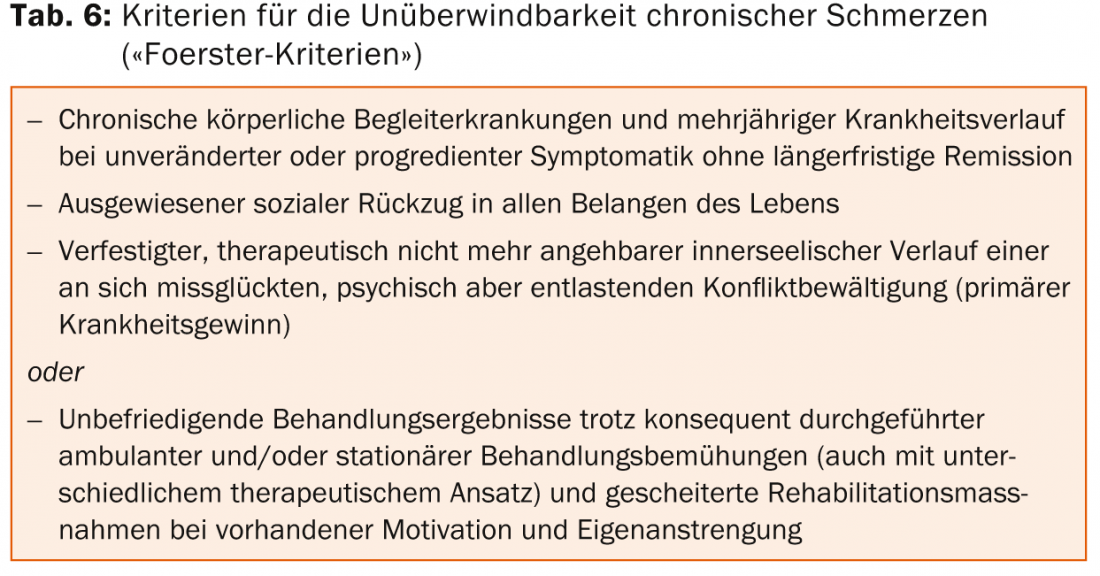

The case law does not take social factors into account. In order to assess the degree of disability, any mental health impairment must be diagnosable with sufficient certainty within the framework of a valid classification system (e.g. somatoform pain disorder F45.4) after exclusion of an organic cause, and the pain occurring in this context must have been assessed as voluntarily insurmountable. Apart from a psychiatric concomitant disease of considerable severity, intensity, expression and duration, which could lead to the insurmountability of the pain (e.g. severe recurrent depressive disorder), voluntary overcoming of pain on the basis of the so-called Foerster criteria is then the focus of the assessment (tab. 6) .

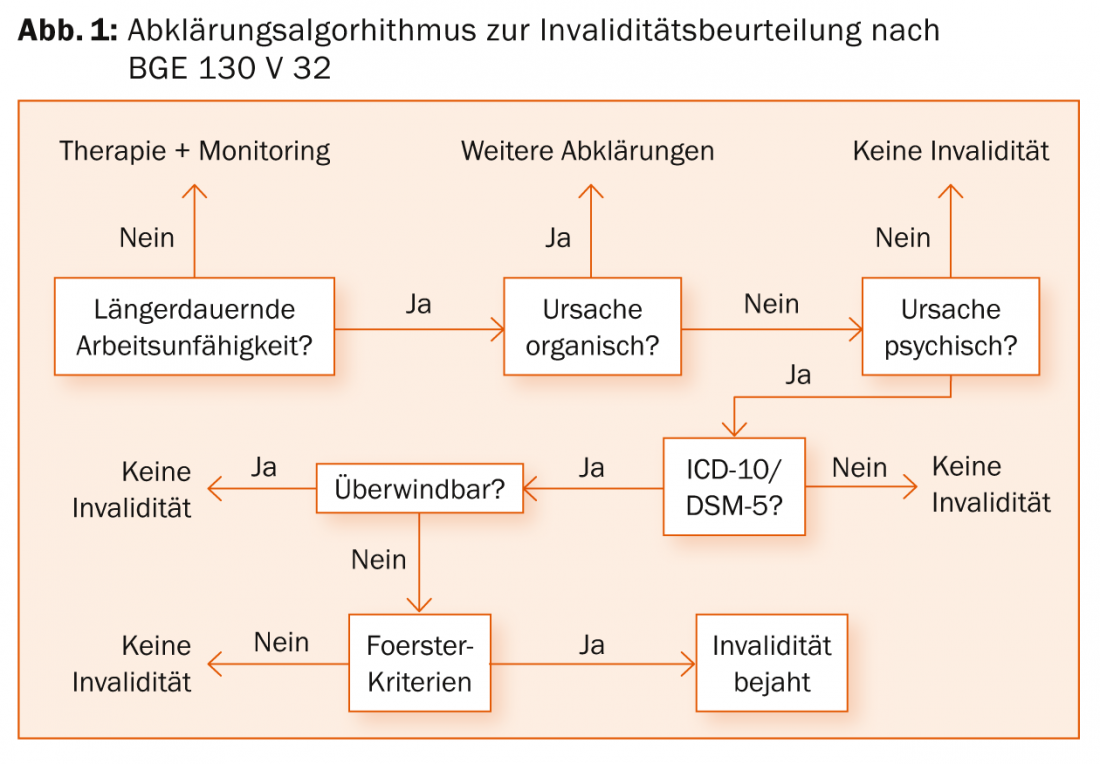

Figure 1 shows the summary algorhithm for the assessment of a pain processing disorder as defined by current case law [10].

Take-home-messages

- Comprehensive semi-structured biopsychosocial anamnesis and assessment with open questioning and active listening in a trusting atmosphere are prerequisites for therapy and assessment of chronic pain – every diagnostic step is also part of therapy.

- State of the art is a multimodal therapy in designated treatment units or networked in the practice in an interdisciplinary team, consisting of various specialists, psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, special therapists, nursing specialists and special therapists – together instead of alone.

- In contrast to medicine, jurisprudence does not follow the bio-psycho-social model of disease, but rather the bio-psychological understanding of disease, which disregards social factors. To assess the degree of disability after prolonged incapacity, voluntary pain overcoming is contrasted with secondary disease gain using the Förster criteria.

PD Stefan Begré, MD, EMBA

Literature:

- Classification of chronic pain : descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms / prepared by the Task Force on Taxonomy of the International Association for the Study of Pain,2nd ed., IASP Press, Seattle, 1994.

- Mackey SC: Central neuroimaging of pain. J Pain 2013; 14(4): 328-331.

- Freud S, Elisabeth von R: In: Studies on hysteria. 1895; GW I: 75-312.

- Melzack R, Wall PD: Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 1965; 150(699): 971-979.

- Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ: Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain 2009; 10(9): 895-926.

- Apkarian AV, et al: Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J Pain 2005; 9(4): 463-484.

- Langewitz W, et al: Evaluation of a two-year curriculum in psychosocial and psychosomatic medicine – dealing with emotions and patient-centered interviewing. Psychother Psych Med 2010; 60(11): 451-456.

- Carragee EJ: Clinical practice. Persistent low back pain. N Eng J Med 2005; 352(18): 1891-1898.

- van Dessel N, et al: Non-pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 11: CD011142.

- Federal Court decision BGE 130 V 352 of March 12, 2004.

- Rief W, et al: The classification of multiple somatoform symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184(11): 680-687.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(1): 16-22.