Spinal muscular atrophy is a rare genetic disorder characterized by the loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord and lower brainstem. In the meantime, experts agree that therapy management must be geared to the individual needs and subjective goals of the person concerned, especially with increasing age. Because these have a great influence on the quality of life.

One in about 10,000 newborns has a gene defect that disrupts impulse conduction in motor neurons. Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a rare, predominantly autosomal recessive muscle disease in which motor anterior horn cells and motor cranial nerve nuclei degenerate. It is the most common hereditary disease resulting in death in infancy and is often diagnosed at a very early age – although not exclusively [1,2]. SMA may also not become apparent until adulthood [3]. This heterogeneity therefore requires individualized therapy that takes into account the disease activity and needs of the patient.

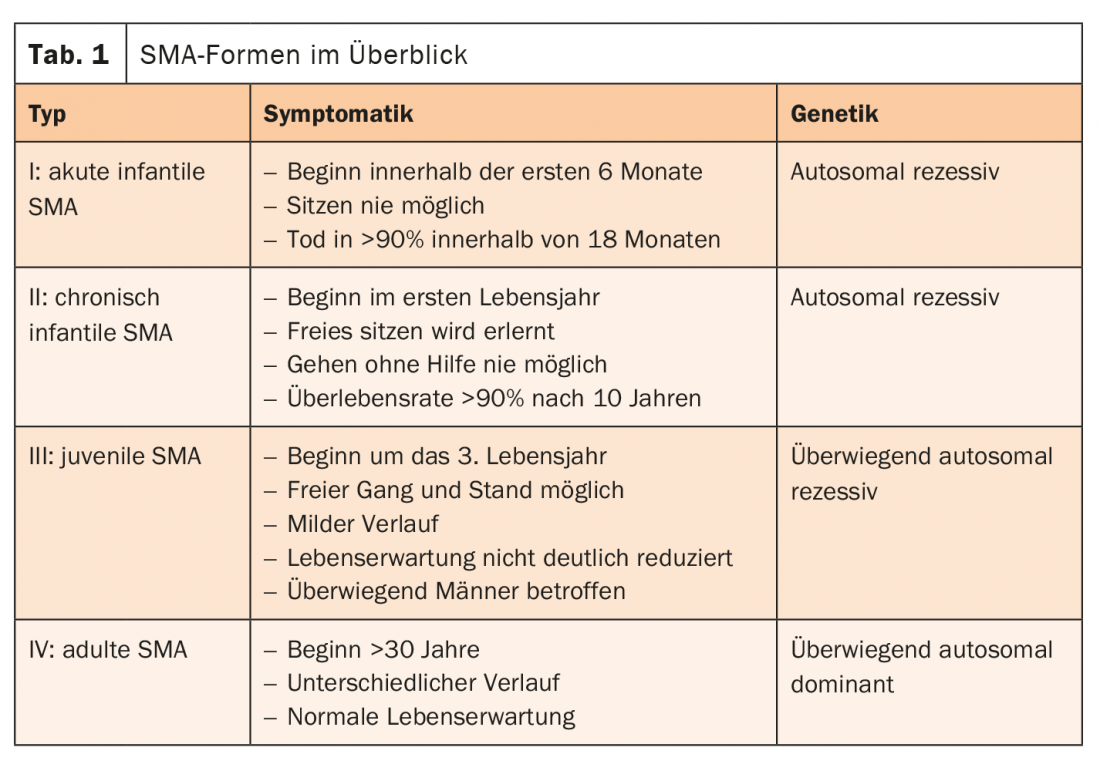

The cause of SMA is usually a defect in the SMN1 gene. Together with the SMN2 gene, it forms the survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein. This plays a central role in the transmission of impulses from the nerve cells to the muscles. If the SMN1 gene fails, the important protein can only be produced by the remaining SMN2 gene. Therefore, the more SMN2 copies are present, the later the onset of SMA and the more favorable the course. Patients with late-onset SMA (types II-IV) often have a normal life expectancy. The SMA forms are differentiated according to distribution pattern, onset of disease, severity and inheritance pattern (Tab. 1) [4].

Screen newborns if possible

A definite diagnosis regarding SMA can only be made by genetic testing. However, because type 1 SMA, if untreated, leads to death or requires permanent mechanical ventilation in 90% of cases by the time the patient reaches two years of age, early identification of the disease with initiation of treatment as soon as possible is indicated. Therapy management is complex and includes acute care as well as measures regarding rehabilitation, orthopedics, respiratory support, physical therapy, and drug interventions.

Therapy successes also with adolescents and adults

The first drug that not only acts symptomatically but also addresses the causes of the disease by correcting the underlying gene defect was approved in 2017 with nusinersen. The antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) is a specific splicing modulator that leaves the genome as it is and enhances the natural function of the SMN2 protein. This allows larger amounts of complete and functional SMN protein to be formed. Now, initial data from a multicenter cohort study have been presented. The main objective of this non-interventional observational study is to investigate the treatment goals and expectations of adult 5q-SMA patients and the subjective treatment satisfaction of patients [5].

The preliminary results show that individual treatment goals are of particular importance. Within the different 5q-SMA types, the goals of therapy vary significantly. Thus, preservation of arm function is one of the most common treatment goals, with a predominance in type 1 and type 2 patients. In patients with SMA type-3, preservation and improvement of leg function is more often prioritized. ASO therapy seems to be suitable for this purpose. Further study results also demonstrate that various motor abilities can stabilize or even clinically relevant motor improvements are possible in adults with 5q-SMA [6-8].

Congress: DGM 2021

Literature:

- Bowerman M, et al: Therapeutic strategies for spinal muscular atrophy: SMN and beyond. Dis Model Mech 2017; 10: 943-954.

- Borasio G, et al: Diagnostics of spinal muscular atrophies. Neurology 2001; 20:113-118.

- www.sma-schweiz.ch/spinale-muskelatrophie/typen-der-proximalen-sma (last accessed on 05.04.2021)

- www.muskelgesellschaft.ch/diagnosen/spinale-muskelatrophien-sma (last accessed on 05.04.2021)

- Meyer, et al: DGN Congress 2020, P333.

- Hagenacker T, et al: Lancet Neurol 2020; 19(4): 317-325.

- Walter MC, et al: J Neuromuscul Dis 2019; 6: 453-465.

- Maggi L, et al: JNNP. 2020, Nov;91(11): 1166-1174.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2021; 19(3): 41 (published 5.6.21, ahead of print).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(8): 45