The concept of overlapping disease entities has changed and the term “asthma overlap syndrome” is no longer propagated. Patients who meet the diagnostic criteria for asthma and COPD should be diagnosed with both. If a COPD patient has an asthmatic component, this should be taken into account accordingly during therapy.

Apart from the full reversibility of the obstructive ventilation disorder, there is no single clearly specific characteristic for asthma or COPD, even if there are some further differential diagnostic clues (Table 1) [1]. Previously, the GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) and GINA (Global Initiative for Asthma) guidelines suggested an initial diagnosis of asthma-COPD overlap syndrome in patients with obstructive airway disease that is not clearly attributable to one of the two entities [1]. Nowadays, however, it is no longer appropriate to speak of a syndrome, but rather of a coincidence, explained Dr. Nikolay Pavlov, University Clinic for Pneumology, Inselspital Bern [2]. According to current understanding, the two respiratory diseases are regarded as different disease entities that can coexist in one patient. “The consensus today is that asthma and COPD can be present in a patient at the same time,” summarized the speaker [2].

Diagnostic challenge with therapeutic implications

The diagnosis is made by synthesizing the findings from repeated examinations and taking into account the response to therapy [1]. Patients who have features of asthma and COPD are more likely to have exacerbations and comorbidities compared to patients who have only one of the diseases, and their lung function and quality of life are also disproportionately reduced [2]. A classic example is the allergic asthma patient with breathing difficulties since childhood who has smoked for decades and developed irreversible bronchial obstruction and emphysema. If patients have an asthmatic component and COPD, pharmacotherapy should mainly be based on the asthma treatment guidelines [2]. This does not rule out the possibility of prescribing other pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatments if this is necessary for COPD, for example, says Dr. Pavlov.

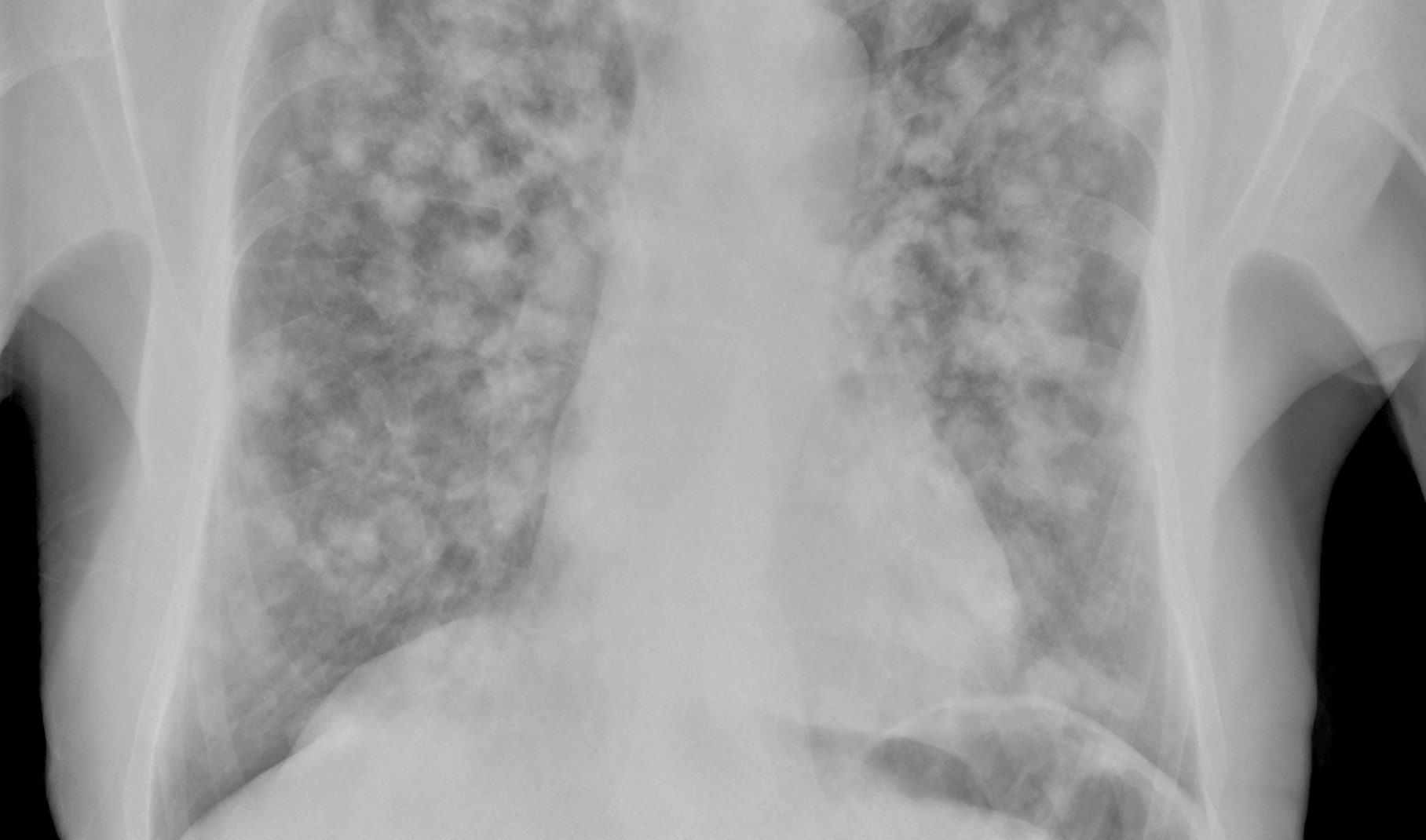

It is often difficult to distinguish between the two diseases simply on the basis of the symptoms. COPD affects the airways in the form of chronic bronchitis, but also the alveoli in the form of emphysema, whereas asthma is generally a chronic airway inflammation, usually accompanied by bronchial hyperresponsiveness [2].

Case study: elderly ex-smoker with respiratory problems

The speaker used a case study to illustrate the complexity of the topic [2]. A man born in 1950 was self-referred due to daily exertional dyspnea (mMRC1-2) and productive cough with whitish sputum. There was no history of asthma in childhood, the patient was an ex-smoker with a total of about 20 pack years and had received a single treatment with a steroid shot and antibiotics years ago as part of an exacerbation. At the initial examination, the following diagnoses were present: arterial hypertension (treatment with amlodipine 5 mg/valsartan, 160 mg), hymenoptera allergy and recurrent chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. The latter had already undergone several operations. The patient had given up smoking several years ago.

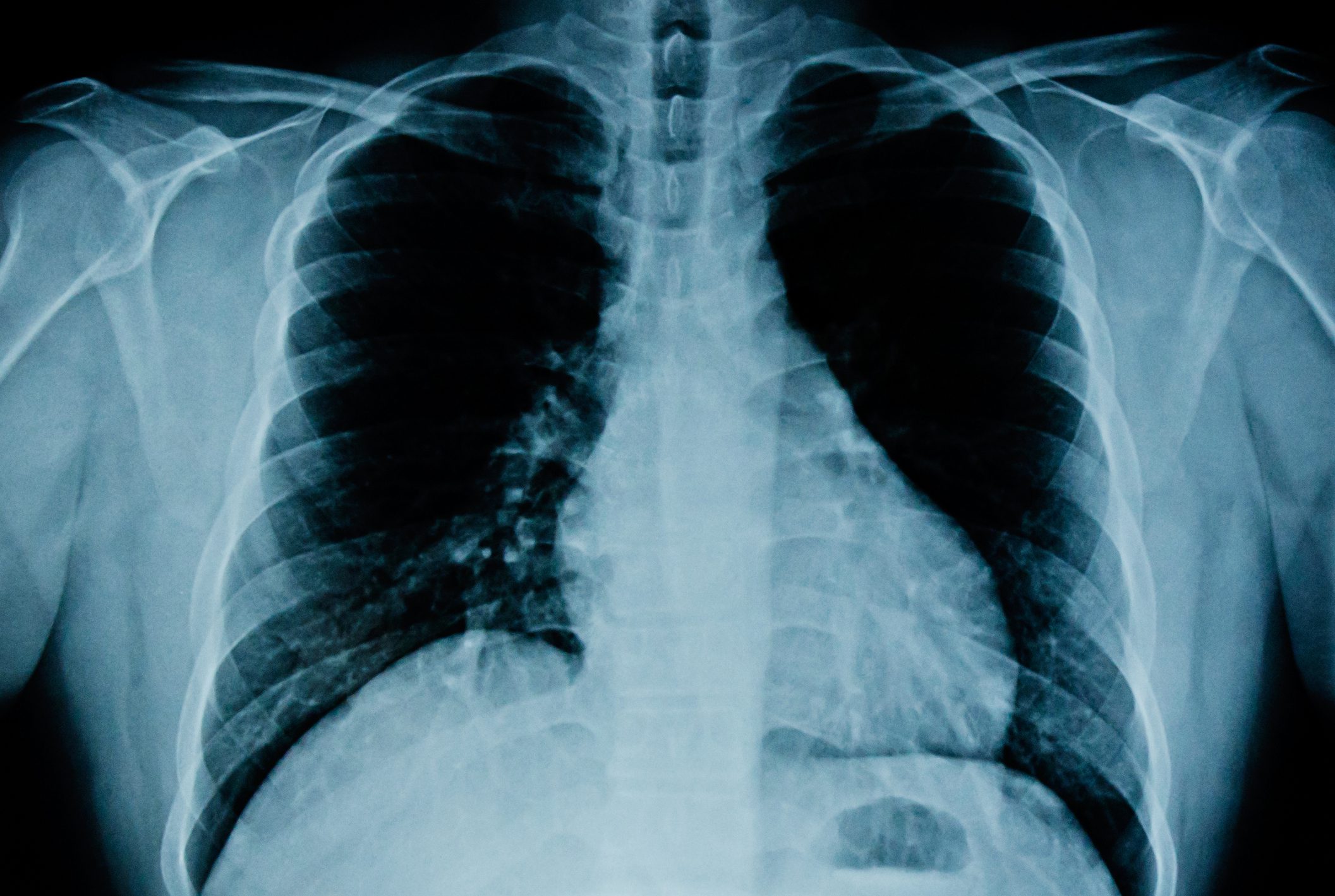

Initial diagnostics and choice of therapy: Spirometry with blood gas analysis was performed. This revealed that the patient had an obstructive ventilation disorder and a reduced FEV1. At that time, the findings suggested COPD according to GOLD stage II with a moderate obstructive ventilation disorder. The total lung capacity proved to be normal; there was no restrictive pulmonary dysfunction and the diffusion capacity was also within the normal range. alpha-1-antitrypsin was also normal.

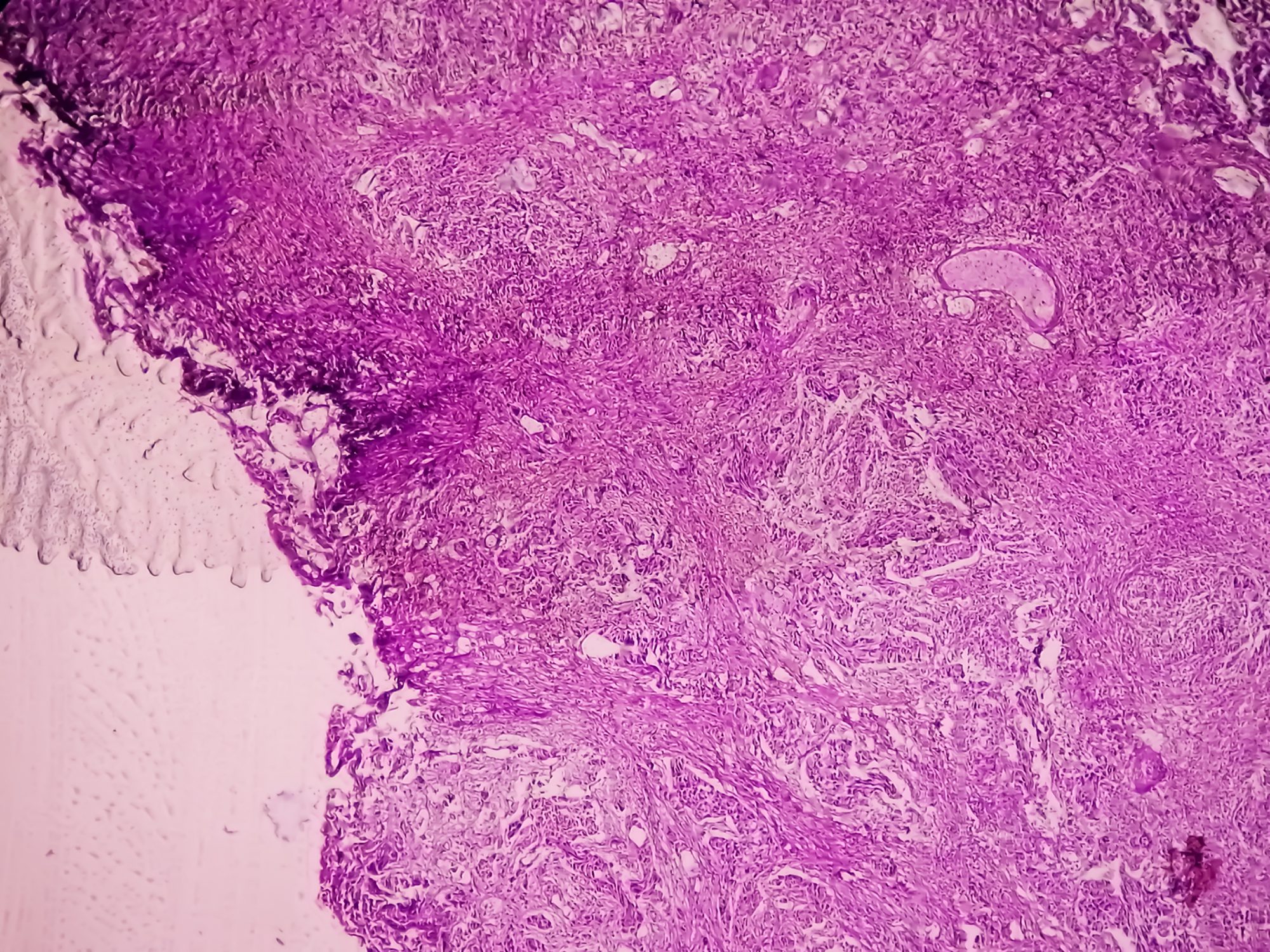

Furthermore, the eosinophils in the peripheral blood were found to be elevated (0.77 G/l; previous value 0.7 G/L). Subsequent histologic examination of the polyp in the right nasal cavity revealed a polypoid configured mucosal fragment with edema, fibrosis, chronic inflammation with moderate eosinophilia; no evidence of malignancy.

Subsequently, inhalation therapy with two bronchodilators (LABA/LAMA) plus ICS was prescribed because the patient was symptomatic and had fairly severely impaired lung function. This was interpreted as an exacerbation. To determine whether reversibility or partial reversibility of lung function could be induced, a steroid boost was administered and ICS were maintained for two weeks. As a result, FEV1 improved; the patient was still obstructive, but partial reversibility of lung function was seen after therapy.

Further investigations and treatment in the course of the disease: The suspicion of an asthmatic component was confirmed by the findings of the imaging examination (computer tomography, CT). This showed that the patient had bronchopathy – in addition to air trapping, the bronchial walls were thickened. There was no evidence of interstitial pneumopathy and no emphysema. Overall, these findings suggest that the asthmatic component is in the foreground, even if COPD cannot be completely ruled out. The patient was subsequently treated with bronchodilator therapy (LABA/LAMA) plus ICS over a period of 3-6 months. This resulted in an approximate normalization of lung function. Although there was still an obstruction, it was only mild and the eosinophilia in the blood almost normalized. At this point, it was concluded that the diagnosis of eosinophilic bronchial asthma was more appropriate – the somewhat delayed response to ICS therapy supported this.

In the further course, there were isolated exacerbations and the decision was made together with the patient to additionally prescribe an anti-IL-5 antibody (mepolizumab). Under this treatment regime, both lung function and symptoms stabilized and the patient no longer had any exacerbations.

Congress: Praxis Update Bern

Literature:

- S2k-Leitlinie zur fachärztlichen Diagnostik und Therapie von Asthma 2023, AWMF-Registernr.: 020-009.

- «Asthma/COPD Overlap-Syndrom», Dr. med. Nikolay Pavlov, Praxis-Update, Bern, 26.10.2023.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023: 18(12): 38–39