Congenital malformations occur in a heterogeneous clinical spectrum. They can be classified according to the criteria of vascular type, hemodynamic efficacy, and embryological stage of development. Basic diagnostics include history, clinical status, duplex sonography, MRI, and D-dimers. Depending on the severity, an individual, interdisciplinary treatment plan must be created.

Congenital vascular malformations (congenital vascular malformations [KVM], angiodysplasia) occur in a heterogeneous clinical spectrum. The individual case is not infrequently characterized by different combinations of these malformations. Although KVMs are not by definition rare diseases of childhood and adulthood, there is medical underuse. In addition to history and clinical status, duplex sonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and a determination of D-dimers are part of the basic examination. Treatments are often lengthy, complex, and require interdisciplinary treatment planning that should include diagnostic, surgical, minimally invasive, as well as psychosomatic aspects. There are only a few centers of excellence in the world that are able to provide the necessary interdisciplinarity not only in terms of treatment, but also across the entire age spectrum of patients. Sick people often experience a veritable odyssey from doctor to doctor. This not only alienates many patients, but in some cases traumatizes them for life due to inadequate treatments.

Congenital vascular malformations

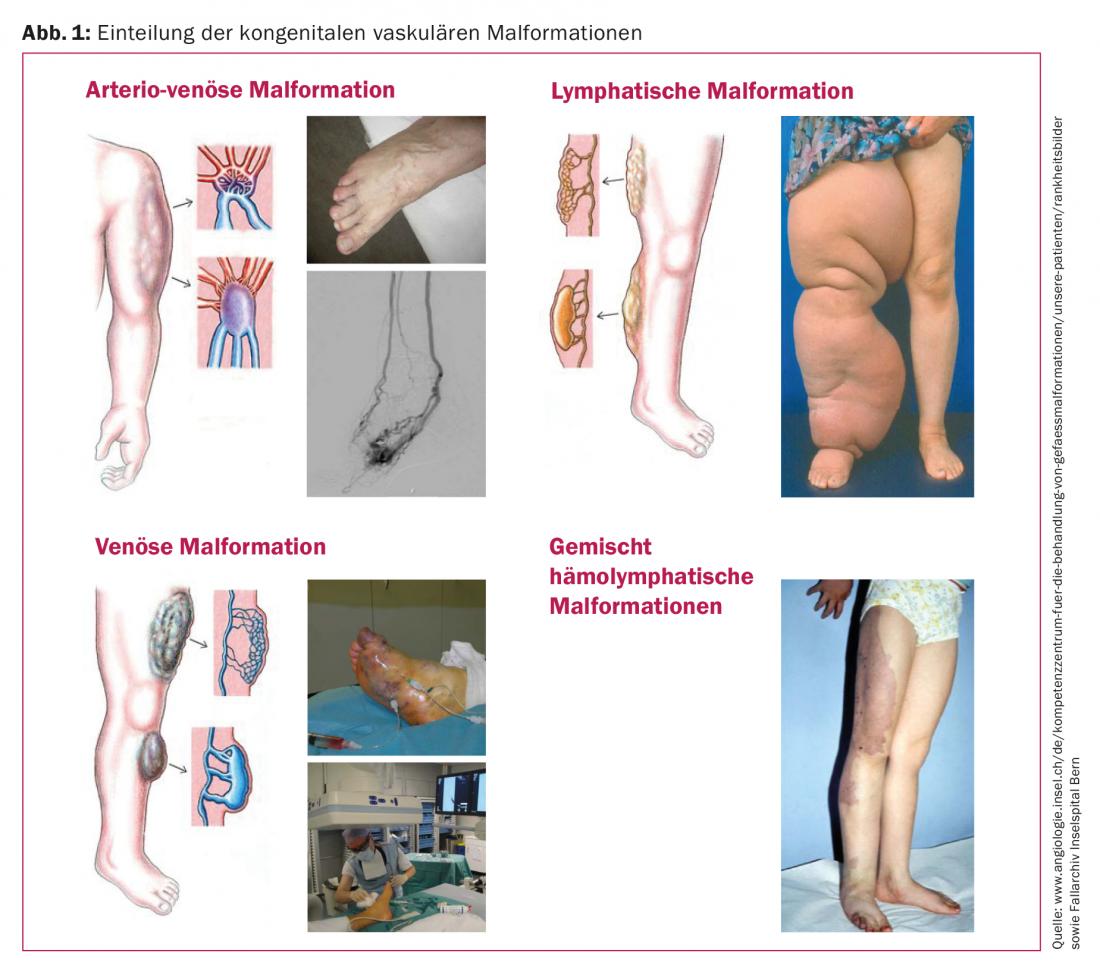

A KVM is a malformation of one or more blood or lymphatic vessels [1]. These include arterial-venous short circuits (AVM), venous malformations (VM), lymphatic malformations (LM), capillary malformations (CM) not infrequently mixed forms, and syndromal pictures such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (Fig. 1).

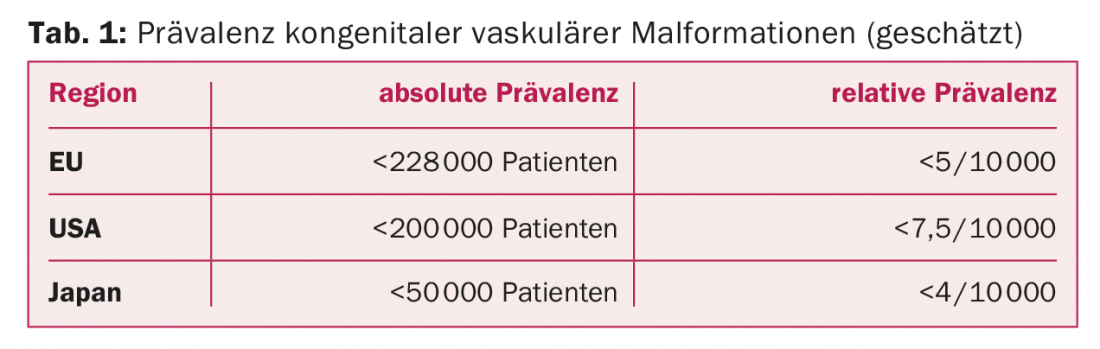

The prevalence is approximately 1.5% of the population with variations according to geographic region (Tab. 1) . It is estimated that there are approximately 1000-1500 patients in Switzerland with KVM requiring treatment. This number increases twofold when visceral, spinal, and intracranial vascular malformations are included. One data source of the existing prevalence in Switzerland is the ICD statistics of hospitals (Swiss Federal Statistical Office). Thus, about 700 potential malformation cases are reported for 2010. This corresponds to about 88 cases per 1 million inhabitants per year. Since miscoding must be assumed due to confounding diagnostic semantics, it is probably safe to assume 100 potential treatment cases per 1 million population.

Cause and complications

KVM are attributed to embryonic maldevelopment. Remnants of the embryonic capillary network remain, which can lead to medical problems. The absolute majority develop from embryologically immature vascular segments (extratruncal vascular malformation) that retain a growth potential after birth similar to that of tumors. In these embryologically immature extratruncal KVMs, uncontrolled progression may occur due to stimulation, e.g., hormone exposure during pregnancy or inadequate treatment. In addition to the vascular system, the skeletal system is most commonly affected with dysproportional growth. Bleeding in patients with associated localized intravascular coagulopathy, heart failure in large arterio-venous malformations, chronic pain conditions in extensive venous malformations, and lymphedema with infections and chronic lymphatic fistulas are just some of the major facets of the usually complex disease manifestations.

Classification

The terminology predominant at the beginning of the 20th century, consisting of proper names and semantics that were difficult to understand, has since been replaced by a logical classification, which has also contributed significantly to optimized treatment concepts, among other things. Because of the broad clinical presentation and in order to plan therapy, KVM are initially evaluated basically according to the following criteria:

- Anatomical assignment of the vessel type (AM, VM, LM, CM) [2].

- Hemodynamics (high flow [AVM] or low flow [VM, LM, CM]) [3]

- Morphological, embryonic assignment (truncal or extratruncal KVM) [4].

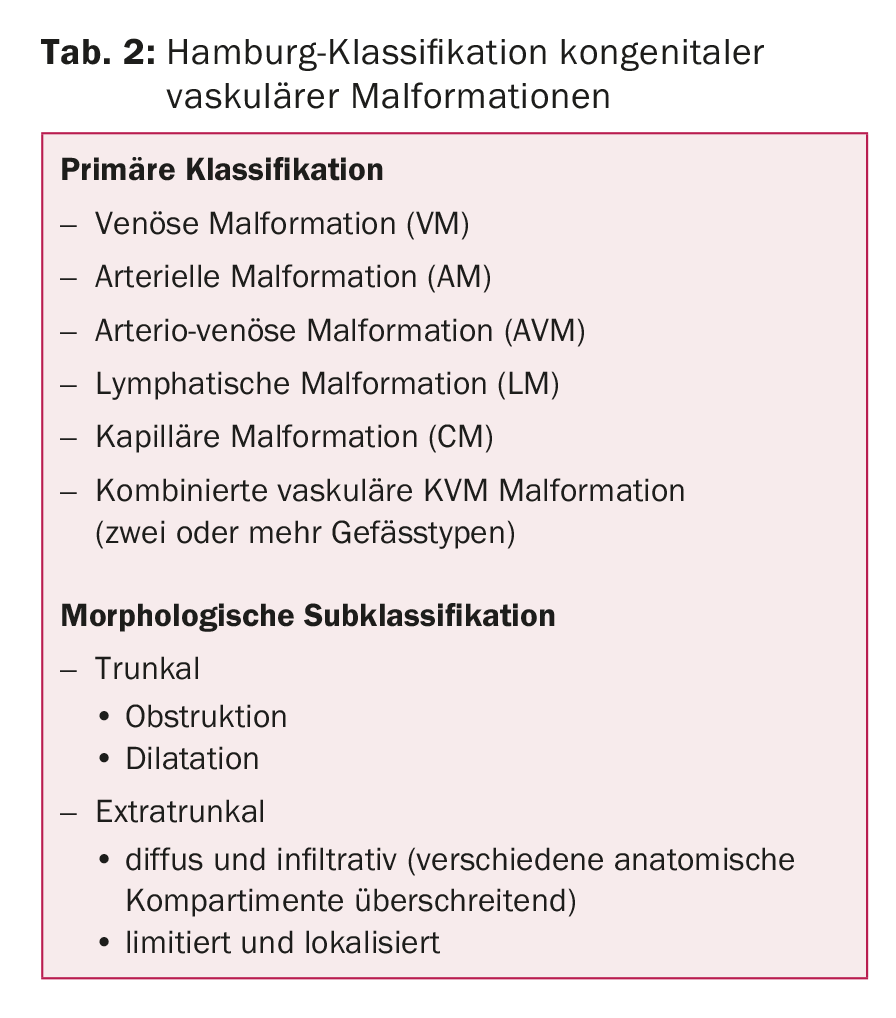

A biological classification of KVM was first published by Mulliken and Glowacki in 1982. Followed by the systematizing Hamburg classification, which has been widely integrated into the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification [4]. In the Hamburg classification, KVMs were for the first time differentiated by anatomical vessel type and by embryological maturity, and a substantial simplification of semantics was thus achieved (Table 2).

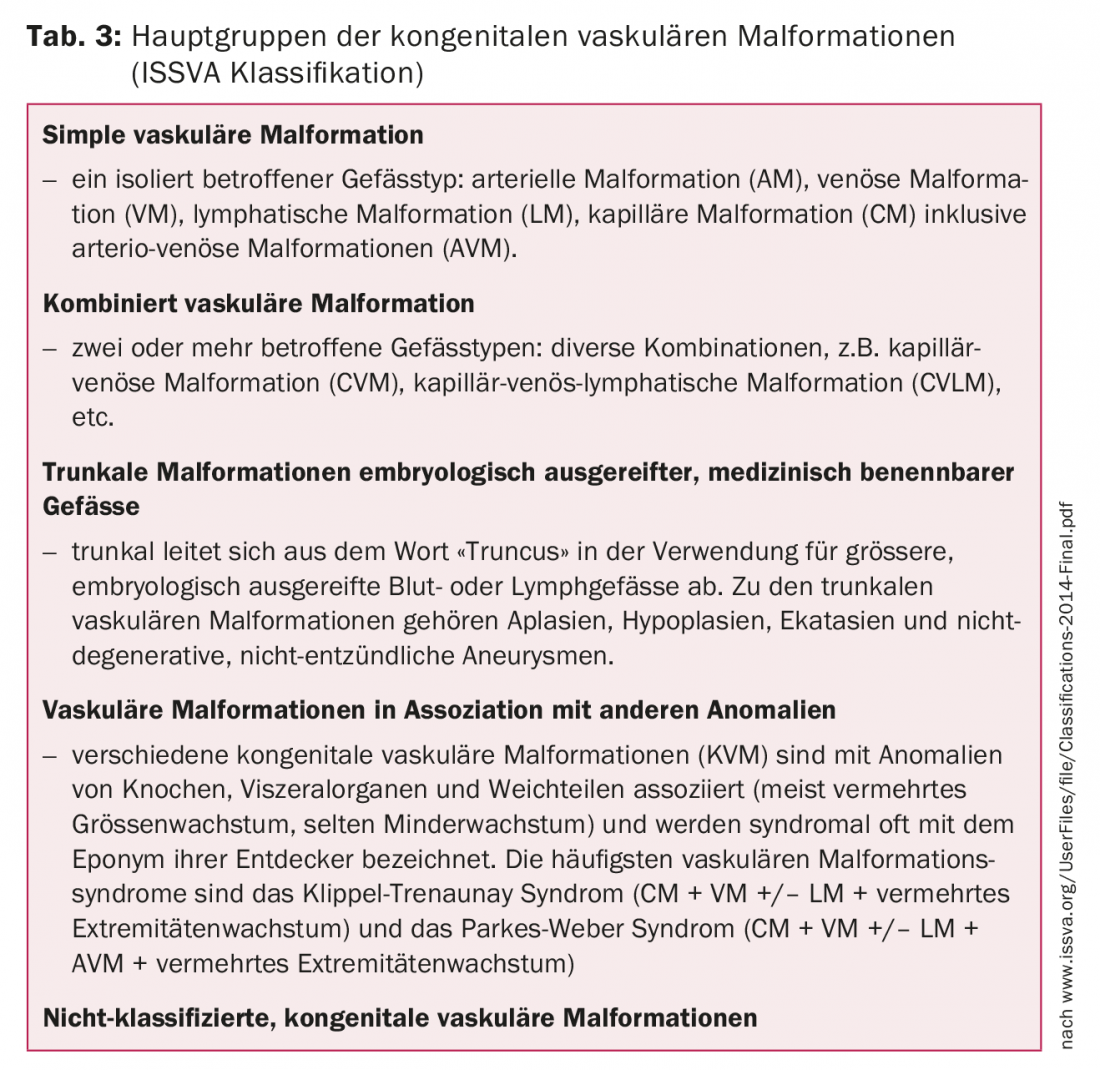

The ISSVA (International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies) classification (Table 3) distinguishes congenital vascular malformations and hemangiomas in vascular anomalies [2,5]. Hemangiomas are considered early vascular tumors (“angiomas”) among the vascular anomalies, but must be differentiated from KVMs with respect to pathophysiology and therapy.

Treatment

Out of the large amount of KVMs, those cases stand out in which there is a serious aesthetic, functional or vital threatening health impairment. There are no evidence-based, standardized treatment pathways for treatment. Each patient must be treated individually and a treatment plan, often extending over years, must be developed together with the patient. In most cases, multiple catheter interventions and/or surgeries are necessary to achieve improvement for the patient with an acceptable risk of side effects.

Most KVMs have anatomic, pathophysiologic, and hemodynamic consequences that, in the absence of treatment in young adulthood, can lead to substantial impairment of various organ systems. The focus is on minimally invasive interventional treatments, most notably endovascular and percutaneous embolization with 96% alcohol [6]. When used selectively, alcohol embolization offers good and long-lasting treatment success with an acceptable risk of complications. Alcohol embolization can be supplemented by the use of various other embolisates and coils. It is critical to have sufficient treatment expertise and to perform staged interventions. Recently, promising results in the treatment of complex KVMs with the mTOR inhibitor Sirolimus® have been reported [7].

Prospective or randomized studies are lacking. Various treatment studies focusing on individual organ systems have evidence levels B and C. The treatment indication can be summarized as follows, irrespective of organ:

- KVM – regardless of whether they are already symptomatic or still asymptomatic – should be eliminated by embolization or surgery because of the usually poor short- but also medium-term prognosis, if the chances of treatment are judged to be good

- In symptomatic KVMs, an indication for treatment is generally accepted. As a rule, priority is now given to endovascular procedures.

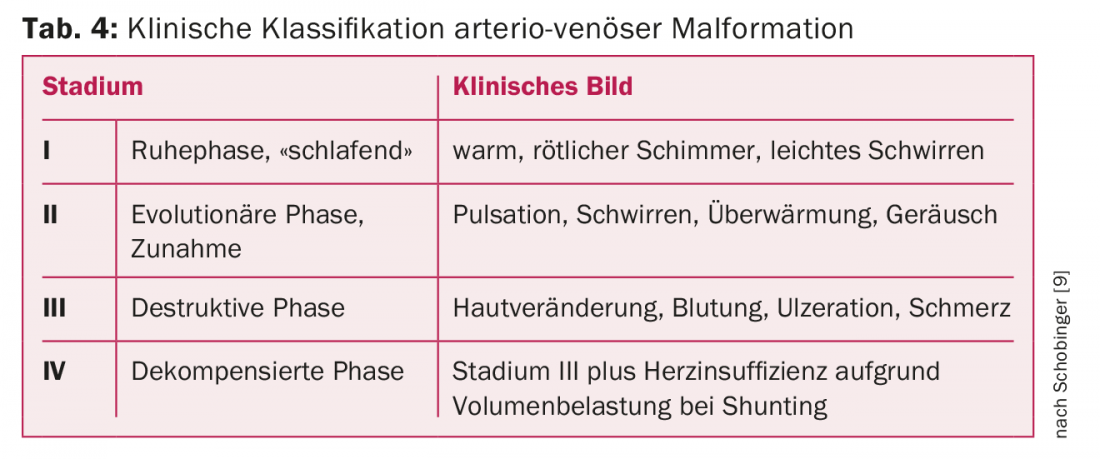

The treatment of extratruncal KVMs, which account for by far the majority of all KVMs, should be left to experienced specialists. For high-flow KVMs, i.e., arterio-venous malformations, there is virtually always an indication for treatment because of flow-related progression. For clinical Schobinger classification of arterio-venous malformations, see Table 4 [8].

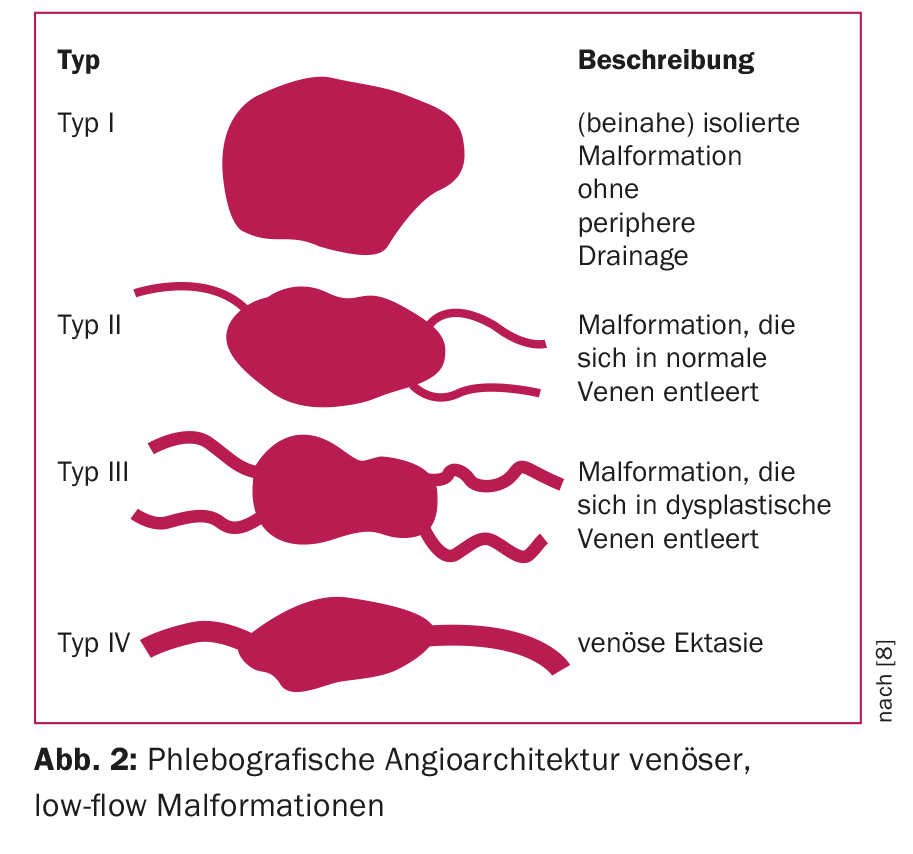

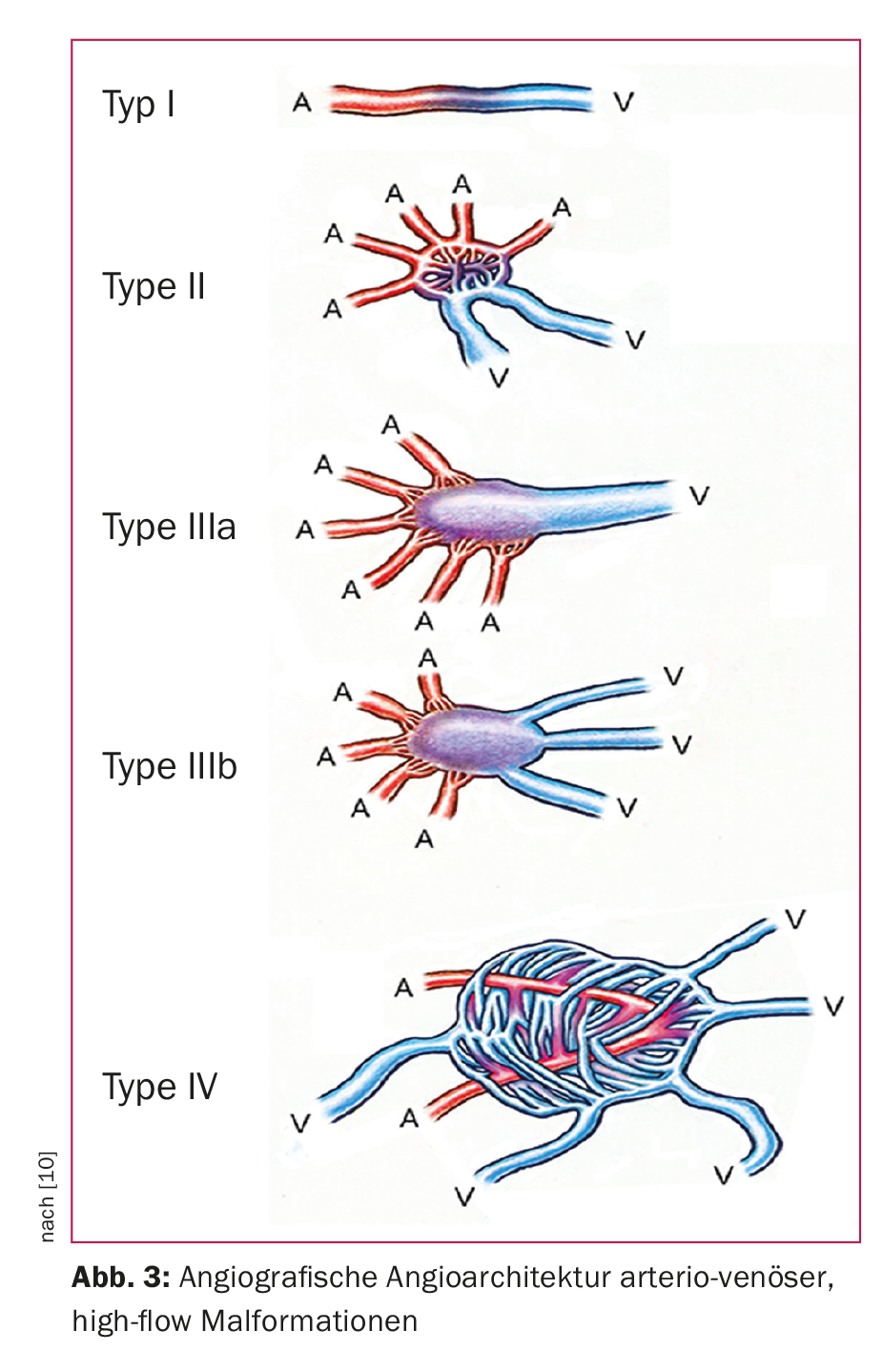

For treatment planning, an additional subclassification according to angiographic aspects (angioarchitecture) has proven useful. Thus, venous low-flow malformations are divided into four types (Fig. 2), a classification that simultaneously corresponds to the degree of difficulty and the risk of complications associated with embolization treatment [8]. For arterio-venous, high-flow malformations, the Wayne-Yakes classification (Fig. 3) has become accepted, which also has a close relation to intervention-specific technique and complication risks [10].

Take-Home Messages

- Basically, the classification of congenital malformations is based on the criteria: Vascular type, hemodynamic efficiency, embryological degree of development (ISSVA classification).

- Basic diagnostics include history, clinical status, duplex sonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and D-dimer determination.

- Stimulation, e.g. hormone exposure during pregnancy or inadequate therapy, can lead to uncontrolled progression.

- There are multiple manifestation forms/sites: skeletal system (dysproportional growth), thrombosis/bleeding (localized intravascular coagulopathy), heart failure (arterio-venous malformations), chronic pain conditions (venous malformations), lymphedema with infections and chronic lymphatic fistulas.

- An individualized, interdisciplinary treatment plan should be developed. Minimally invasive, interventional treatment methods are used in the majority of cases, and a multistage approach is recommended to minimize complications.

Literature:

- Mulliken JB, Glowacki J: Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg 1982; 69: 412-422.

- Wassef M, et al: Vascular Anomalies Classification: Recommendations From the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 2015; 136: e203-214.

- Frey S, et al: Hemodynamic Characterization of Peripheral Arterio-venous Malformations. Ann Biomed Eng 2017; 45: 1449-1461.

- Lee BB, et al: Terminology and classification of congenital vascular malformations. Phlebology 2007; 22: 249-252.

- Dasgupta R, Fishman SJ: ISSVA classification. Semin Pediatr Surg 2014; 23: 158-161.

- Do YS, et al: Ethanol embolization of arteriovenous malformations: interim results. Radiology 2005; 235: 674-682.

- Triana P, et al: Sirolimus in the Treatment of Vascular Anomalies. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2017; 27: 86-90.

- Puig S, et al: Vascular low-flow malformations in children: current concepts for classification, diagnosis and therapy. Eur J Radiol 2005; 53: 35-45.

- Lee BB, et al: Consensus Document of the International Union of Angiology (IUA)-2013. Current concept on the management of arterio-venous management. Int Angiol 2013; 32(1): 9-36.

- Yakes W, Baumgartner I: Interventional treatment of arterio-venous malformations. Vascular Surgery 2014; 19: 325-330.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(5): 21-24